BUSINESS MODEL ANALYSIS OF SEAMLESS ACCESS IN

SOUTH EAST ASIA

Chin Chin Wong, Andy L. Y. Low, Pang Leang Hiew

British Telecommunications (Asian Research Centre), Cyberview Lodge Office Complex, Hibiscus Block, First Floor,

63000 Cyberjaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia.

Keywords: Fixed mobile convergence, telecommunications, business models, evolutionary process.

Abstract: Fixed mobile convergence (FMC) will be one of the strongest trends in telecommunications in the near

future. Given the choice, most consumers would want to use a single handset yet do not want to pay the

premium when at home or in the office. Even though seamless network integration will still take some time

to become reality, there are many convergence opportunities that are currently being exploited. Only by

truly reflecting customer needs with a broad and flexible portfolio of products and services that shield

customers from underlying network technologies can players in the industry meet the challenge and promise

of convergence. This paper aims to discuss business models to aid in addressing one of the most common

issues facing executives: aligning IT with the business. This study analyses business models to examine

FMC from multiple perspectives to understand how carrier differentiates its product offerings, acquires and

keeps customers, positions itself in the competitive market as well as captures profit. The paper reports the

findings on the evolutionary processes towards FMC development that could be used to derive architecture

to serve as a guide for players in the industry and to outline suitable approaches to encourage mass market

adoption of FMC services in South East Asia.

1 INTRODUCTION

Currently, the domestic telecom service market is

divided between fixed-line and mobile providers. As

such, not only networks, but also operators and

services are evidently divided into two markets (Lee

& Han, 2005). These result in inconveniences for

users, who have to subscribe to different providers,

pay two bills, and use two different handsets if they

want to utilise both fixed and mobile telecom service

(Lee & Han, 2005). On top of these, fixed-line

services and wireless services are offered via

separate terminals (Lee & Han, 2005). The merits of

FMC become clear when both fixed and wireless

services can be accessed at the same time via a

single terminal, and users only receive one bill from

a single telecom operator (Lee & Han, 2005).

Although seamless network integration will still

take some time to become reality, there are many

convergence opportunities that are currently being

exploited. Only by truly reflecting customer needs

with a broad and flexible portfolio of products and

services that shield customers from underlying

network technologies can players in the industry

meet the challenge and promise of convergence

(Costello & Knott, 2005). FMC has started to take

shape: prototypical services for enterprise and home

users are in place in the developed markets of

Europe, North America and Asia; the launch of

bundled services and voice over IP (VoIP) over

wireless local area network (WLAN), as well as

industry consolidation and integration of networks

and platforms around Internet Protocol (IP) – are all

pointing towards convergence.

Accenture defines FMC as any service or

customer experience that leaves the customer

agnostic as to the underlying technology providing it

(Costello & Knott, 2005). For many service

providers, FMC implies seamless integration of

mobile and fixed voice telephony networks (Costello

& Knott, 2005). According to Costello and Knott

(2005), this highly network-centric view defines a

future that may occur in the next five years, but

omits a broad range of other convergence

opportunities that are happening either now or in the

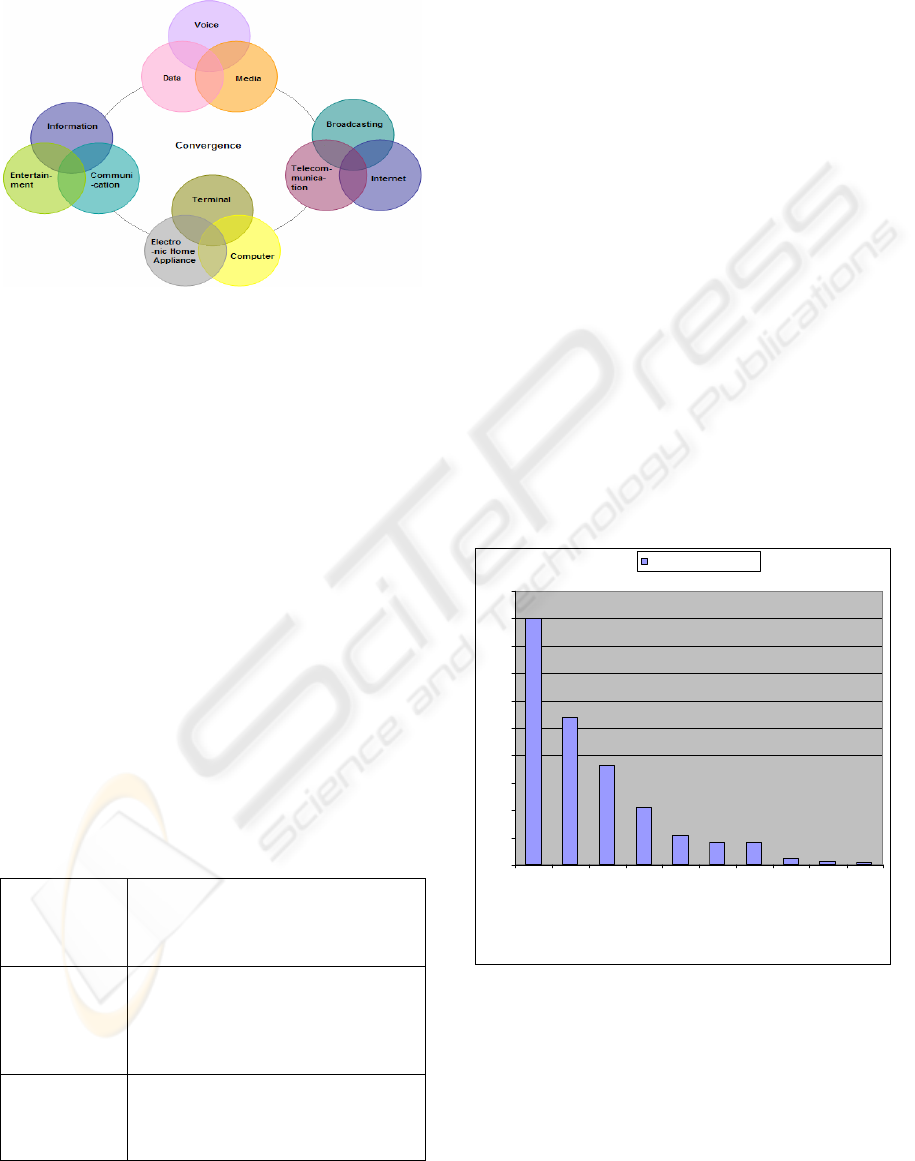

near future. Referring to Figure 1, sooner or later,

when users not only can seamlessly roam between

local and wide area networks but also carry services

51

Chin Wong C., L. Y. Low A. and Leang Hiew P. (2006).

BUSINESS MODEL ANALYSIS OF SEAMLESS ACCESS IN SOUTH EAST ASIA.

In Proceedings of WEBIST 2006 - Second International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies - Society, e-Business and

e-Government / e-Learning, pages 51-58

DOI: 10.5220/0001243200510058

Copyright

c

SciTePress

such as address books, video watching, voice mail

and customer service capabilities with them, the

final objective of FMC will be reached (Costello &

Knott, 2005).

Figure 1: Convergence Model (extracted from Lee & Han,

2005).

By taking customers’ perspective into account, a

wider range of convergence opportunities emerges

that are much nearer at hand than the long-term goal

of a seamless network (Costello & Knott, 2005).

FMC will result in field collapse of services,

expansion and deepening of competitive boundary,

and change of value-creation element as shown in

Table 1 (Lee & Han, 2005).

These changes need to be taken into account

when analysing business models to enable carriers to

look at the full breadth of their ability to meet

customers’ demand for new experiences. Creating

the breadth of portfolio, features, and functionality

to achieve it will require an equally wide range of

commercial and business models (Costello & Knott,

2005). Acquisition and merger is one possible route,

while the creation of alliance, partnerships, and

virtual network operator relationships are the other

possible ways (Costello & Knott, 2005).

Table 1: The Effect of Convergence (extracted from Lee

& Han, 2005).

Field collapse

of services

• The change of value chain

• The change of service value

system

• Ambiguity of fixed business

Expansion

and deepening

of competitive

boundary

• Competition expansion in same

industry

• Potential competition among

different industry

• Strategic alliance expansion

Change of

value-creation

element

• The diversity of demand such as

entertainment, communication,

and information

• Seamless and ubiquitous service

To meet the challenges of FMC, carriers will

have to radically rethink their approaches to new

products and services development (Costello &

Knott, 2005). They will need to create a varied

portfolio of products and services and the ability to

bring these to markets in weeks rather than months

to gain competitive advantages (Costello & Knott,

2005). These portfolios will need to be highly

flexible and adaptable, as it is difficult to predict

which will be the killing applications in this market.

2 CURRENT TRENDS AND

GROWTH

2.1 Fixed-Line Market

Not all Asia Pacific markets have the high fixed-line

penetration of Western Europe. Countries such as

Thailand and Philippines have fixed-line penetration

rates of less than 15 percent, well below the average

of 51 percent in Western Europe as of 2004 (Swift &

Wilson, 2004). In these markets, mobile is already

the dominant voice carrier. The drivers and timeline

for FMC in South East Asia are a little different

compared to Europe and America.

45.03

26.86

18.1

10.49

5.41

4.12

3.94

1.12

0.68

0.26

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Si

n

ga

por

e

Bru

ne

i

Dar

u

ssa

l

am

Malays

i

a

Thailand

V

i

e

t

nam

Phil

i

p

pi

n

e

s

I

n

dones

i

a

Laos

M

y

anmar

C

a

m

bo

d

ia

Penetration Rate (%)

Figure 2: Main Telephone Lines per 100 Inhabitants,

South East Asian Countries, 2003 (extracted from MCMC,

2005b).

Referring to Figure 2, apart from Singapore, all

the other countries in South East Asia have main

telephone lines per 100 inhabitants of less than 30

percent. Malaysia stands at 18.1 percent as of 2003.

WEBIST 2006 - SOCIETY, E-BUSINESS AND E-GOVERNMENT

52

Without fixed-line infrastructure, FMC is not a

side-scale option for most developing markets at

present (Swift & Wilson, 2004). The deployment of

broadband infrastructure will determine the time and

scale for FMC (Swift & Wilson, 2004). Unlike in

Europe and America, the rollout of broadband is

crucial for the introduction of FMC due to the very

low fixed-line penetration rate (Swift & Wilson,

2004). Increasing broadband penetration will create

a VoIP revolution, decreasing the price of voice and

creating a mobile premium (Swift & Wilson, 2004).

Once this has occurred, FMC will become an

attractive proposition for both operators and

consumers in South East Asia.

Internet access options in South East Asia are

generally fragmented. For example, the

telecommunications and information infrastructure

in the Philippines is still relatively underdeveloped

and largely concentrated in metropolitan areas

(Lallana, 2003). Low personal computer penetration,

relatively high Internet access costs and bandwidth

limitations have slowed down the adoption of the

Internet for higher-end uses in Philippines (Lallana,

2003). In 2003, personal computer penetration in

Philippines is estimated at 1.9 for every 100 persons;

Internet penetration is at 6 for every 100 persons (or

4.5 million of the total 76.5 million Filipinos)

(Lallana, 2003). Of these Internet users, 3.1 million

(about 70 percent) are said to access the Internet

using prepaid cards at Internet cafés (Lallana, 2003).

The Philippine archipelago is made up of 7,107

islands and this makes connecting residents on all

islands via cable a cumbersome and expensive task.

In Malaysia, there are 353,978 broadband

subscribers (penetration rate of 1.35 percent) and

around 10,710,000 Internet dial-up subscribers

(penetration rate of 13.7 percent) as of the second

quarter of 2005 (MCMC, 2005b). Statistics indicate

that as of the end of second quarter in 2002, there

were 2.3 million Internet subscribers in the country,

with the number of users being almost 7 million

(MCMC, 2005b). In comparison, in 1997, just 5

years earlier, the figures were a mere 0.2 million and

0.6 million respectively (MCMC, 2005b).

While the figures may seem impressive, it is

important to take note that similar official statistics

indicate that the digital divide in Malaysia is still

very wide. For example, 34.2 percent of the

residents in Kuala Lumpur are Internet dial-up users

while only 4.2 percent of the residents in Sabah are

Internet dial-up users as of the first quarter in 2005

(MCMC, 2005b). 79.2 percent of the population in

Kuala Lumpur use cellular phones while only 26.7

percent of the population in Sabah use cellular

phones (MCMC, 2005b).

While deployment of broadband infrastructure in

underdeveloped areas ensures that the population

residing in these areas are always connected, it has

been argued that these residents may not even have

the need to get connected. Therefore, the cultivation

of access to personalised information anywhere and

anytime is also seen as an important driver affecting

the diffusion of FMC solutions.

South East Asian countries with minimal fixed-

line penetration and without a push towards

broadband infrastructure rollout are a different

prospect for FMC services. FMC will most likely

come in the form of bundling bills and “home-zone”

tariff for mobiles (Swift & Wilson, 2004).

Operators, driven by fiercely competitive market

conditions, will utilise these forms of FMC as a

means of differentiation (Swift & Wilson, 2004).

FMC handsets will not appeal in underdeveloped

markets until the rollout of broadband infrastructure

makes it a feasible solution (Swift & Wilson, 2004).

2.2 Mobile Market

On the other end, high penetration rate of mobile

devices in a particular country indicates that the

consumers are either always on the move or reside in

remote areas. These consumers may require specific

services to suit their needs.

Figure 3 shows that mobile phone penetration

rate in South East Asian countries is generally

higher compared to fixed-line penetration rate. The

mobile market in Malaysia continues to grow

increasingly competitive. Declining Average

Revenue per User (ARPU) are forcing telcos to seek

other means of profits. Value-added mobile data

services were expected to foster industry growth.

According to studies conducted by Malaysian

Communications and Multimedia Commission

(MCMC) by the end of 2004, there were 14,455,000

mobile subscribers in Malaysia. This makes up

penetration rate of 55.9 percent, making it the

second highest in Asia after Singapore (MCMC,

2005a). Whether FMC services will take off in the

local marketplace and when this will happen depend

very much on the interaction between cellular

operators and other parties to offer FMC services.

Whether appropriate applications can be developed

and whether these are introduced via the appropriate

marketing mix become crucial (IDC, 2003). Low

personal computer penetration that hinders access to

the Internet via desktop, together with a high level of

interest in new mobile technologies among the Asian

BUSINESS MODEL ANALYSIS OF SEAMLESS ACCESS IN SOUTH EAST ASIA

53

youth, combine to create an immense opportunity

for FMC services in Malaysia (Lee, 2002).

82.25

40.06

43.9

39.42

2.36

26.95

8.74

1

0.12

3.52

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Si

n

g

a

p

o

re

Br

un

e

i

Dar

u

s

s

ala

m

M

a

l

a

y

sia

T

h

a

i

land

Viet

n

am

P

hi

l

ippines

I

n

d

o

n

e

s

i

a

L

a

o

s

M

y

a

n

mar

C

amb

o

d

i

a

Penetration Rate (%)

Figure 3: Cellular Phones per 100 Inhabitants, South East

Asian Countries, 2003 (extracted from MCMC, 2005b).

3 BUSINESS MODELS

Similar to other emerging industries, FMC is

characterised by a continuously changing and

complex environment, which creates uncertainties at

technology, demand and strategy levels (Porter,

1980). Porter (1980) asserts that it is possible to

generalise about processes that drive industry

evolution, though their speed and direction vary.

According to Ollila et al. (2003), these processes are

of dissimilar types and are associated to:

• Market behaviour

• Industry innovation

• Cost changes

• Uncertainty reduction

• External forces, such as Government policy and

structural change in adjacent industries

Each evolutionary process recognises strategic

key issues for the companies within the industry and

their effects are usually illustrated as either positive

or negative from an industry development

perspective. For example, uncertainty reduction is an

evolutionary process that leads to an increased

adoption of successful strategies among companies

and the entry of new types of companies into the

industry. Both of these effects are considered to

contribute to industry development with regards to

the FMC value web. The technological uncertainties

are typically caused by rapid technological

development and the battles for establishing

standards, which are typical in the beginning stages

of the life cycle of a particular industry due to a

technological innovation (Camponovo, 2002).

Concerning demand, despite the generalised

consensus about the huge potential of FMC, there

are many uncertainties about what services will be

developed, whether the users are willing to pay for

them and the level and time frame of their adoption

(Camponovo, 2002).

Finally, strategic uncertainties are a common

situation in emerging industries (Porter, 1980). A

clear framework is required in order to permit

players within the FMC value web to concentrate on

the most critical part of their businesses and prevent

them from repeating the costly mistakes of the

recent past by entering, and subsequently exiting,

non-core businesses and markets.

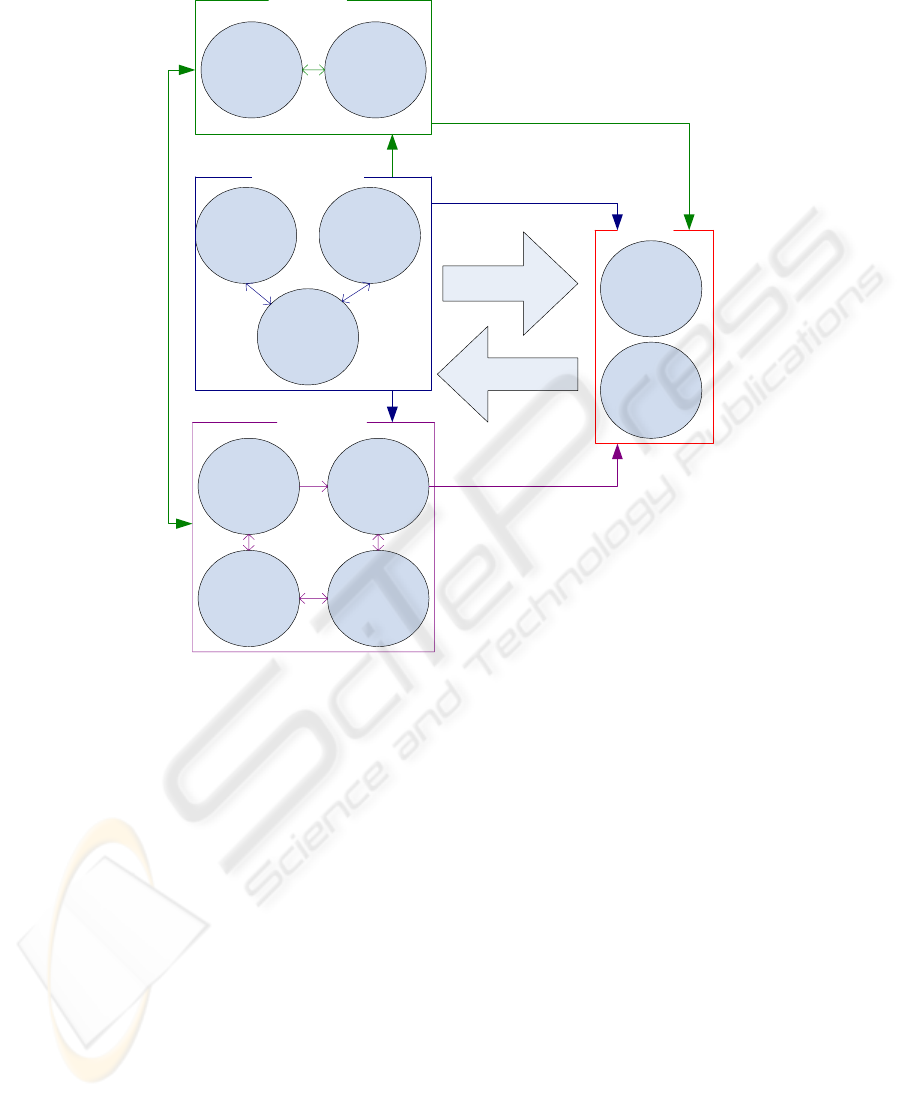

Figure 4: FMC Market Framework (extracted from

Camponovo & Pigneur, 2003).

Based on these observations, a FMC framework

(see Figure 4) has been inspired by the works of

mobile market scorecard framework (Camponovo &

Pigneur, 2003). The objective in this paper is to

conceive a stakeholders’ map for FMC industry. The

underlying idea is that by taking viewpoints from

different complementary perspectives and putting

them all together, one can better understand the

stakeholders and processes involved in the industry.

WEBIST 2006 - SOCIETY, E-BUSINESS AND E-GOVERNMENT

54

4 CONVERGENCE DIRECTION

ANALYSIS

Taking customers’ perspective offers a broader

range of convergence opportunities. Despite the

wide disparity in the cost of mobile and fixed

minutes, many consumers prefer the convenience

and usability of their mobile phones (Costello &

Knott, 2005). The recent rise in broadband adoption

has also created a demand for convergence in the

opposite direction (Costello & Knott, 2005).

Consumers want to see the new services they receive

at home or office to be replicated on the move, with

devices such as Blackberry, which allow mobile

access to e-mail, address book and calendar

(Costello & Knott, 2005).

The trend of fixed-line customers substituting

VoIP minutes for fixed-line minutes continues in

spite of unresolved issues around emergency calls

and dial-tone access (Costello & Knott, 2005). A

research conducted by Accenture’s Communications

Industry Group shows that it is the entire VoIP user

interface, with integration of telephone with chat and

address book capabilities, is the draw for customers

(Costello & Knott, 2005).

According to a study conducted by Ovum, VoIP

will drive the development of FMC (Swift &

Wilson, 2004). Converged IP platforms in the

enterprise space and the growth of broadband will

facilitate the rapid emergence of VoIP (Swift &

Wilson, 2004). Ovum expects that VoIP will

speedily become the voice carriage standard for

corporate with IP-VPNs and an increasingly

common value-added offering for broadband

services (Swift & Wilson, 2004). This will put

pressure on fixed voice charges, increasing the

premium for mobile services, and further eroding

PSTN revenue (Swift & Wilson, 2004).

Despite the release of first-generation Bluetooth

and Wi-Fi handheld devices, issues such as battery

lifespan and hand-over require further refinement

(Swift & Wilson, 2004). However, convergence

opportunities need not only rely on network

convergence. This can be as simple as offering

customers a single billing plan or replicating

functionality across devices (Costello & Knott,

2005). Wireless technologies also provide the

opportunity to bring together a wide group of

devices. Full convergence of the user experience and

product functionality may be attained this way even

before the underlying convergence and integration is

fully realised at the network level (Costello & Knott,

2005). This is depicted in Figure 5.

Convergence at the services level is already

happening. Users may use a phone to watch

television, listen to the radio, chat, play games,

browse the Internet, access location-based services;

for video conferencing purposes and so forth – all in

one handset.

GSM-evolved networks will be integrated with

WLANs, PANs (Personal Area Network), BANs

(Body Area Network), and other wireless

technologies to form ubiquitous all-IP environment.

In a converged world, an extended personalisation

concept is required. Mass customisation to cater for

the needs of each individual enables one-to-one

effective marketing (Nokia, 1999). The aspects

covered include user preferences, location, time,

network, and terminal have to be integrated and the

relationship between these aspects must be taken

into consideration to design business models. Next-

generation handsets are capable of a combination of

services available on PDA (Personal Digital

Assistant), mobile phone, radio, television, and even

PCS

(IS-95A)

- Voice

- 14.4 ~ 64 kbps

IS-95B

Mobile

Wireless

Fixed

CDMA2000

1X

1X

EV-DO

1X

EV-DV

W-CDMA

- High Capacity

Voice

- 144 kbps

- 2.4 Mbps

Packet

IEEE

802.11a

IEEE

802.11g

Past Present Future

- High Capacity

Voice

- 384+ kbps

Packet

- 5 GHz

- 54 Mbps

- 2.4 GHz

- 1 Mbps

IEEE802.11b

- 2.4 GHz

- 54 Mbps

PSTN

Modem

IEEE

802.11a

ADSL

- 1 – 8 Mbps

VDSL

- 50 Mbps

FTTH

- Hundred Mbps

All IP

Network

Seamless

Access

IEEE

802.16

- 2 – 11 GHz

- 70 Mbps

IEEE

802.15.3a

- 3.1 – 10.6 GHz

- Varies depending

on modulation and

channel bandwidth

Figure 5: The Development of Network (adapted from Lee & Han, 2005).

BUSINESS MODEL ANALYSIS OF SEAMLESS ACCESS IN SOUTH EAST ASIA

55

remote control. This means that various market

segments will emerge for the use of FMC services

and applications.

Figure 6: The Development of Services (adapted from Lee

& Han, 2005).

When multimedia becomes inevitable, the need

for guaranteeing certain levels of Quality of Service

(QoS) becomes imminent. In mobile environment

where users on the move tend to change networks

more frequently, QoS guarantees will lead to the

need for dynamic personalisation (e.g. content

tailoring) on network and service level. On top of

this, the optimisation of content for a given

geographical market is a necessity for making any

given application a success (Travish &

Smorodinsky, 2002). This means that

personalisation can be achieved by offering location-

dependent information to users on the move.

Figure 7: The Development of Terminal (adapted from

Lee & Han, 2005).

Convergence at terminal level is also happening.

The handsets of the future will be more powerful,

less heavy, and comprise new interfaces to the users

and to new networks (Andreou et al., 2002).

Nonetheless, the more features built into a device,

the more power it requires. As a result, the higher

the performance of the device, the faster it drains the

batteries. Furthermore, wireless data transmission

consumes a lot of energy (Schiller, 2000).

In spite of the rapid development of mobile

computing, the mobile devices exhibit some serious

drawbacks compared to desktop systems in addition

to the high power consumption (Andreou et al.,

2002). Interfaces have to appear small enough to

make the device portable. Thus, smaller keyboards

or hand scribing are used, which are frequently

difficult to use for typing due to their limited key

size, or current limitations of hand scribing

recognition (Andreou et al., 2002). Furthermore,

small displays offer limited capabilities for high

quality graphical display. Therefore, these devices

have to use new ways of interacting with a user,

such as, voice recognition and touch sensitive

displays (Schiller, 2000). Figure 7 shows the

development of terminals over the past decade.

The evolution of radio and mobile core network

technologies over the last two decades has enabled

the development of the ubiquitous personal

communications services, which can provide the

mobile user with voice, data, and multimedia

services at any time, any place, and in any format

(Lin & Chlamtac, 2001). Business opportunities for

such services are tremendous, since every person

could be equipped, as long as the service is fairly

inexpensive (Andreou et al., 2002).

The advent of FMC has ushered in a good deal of

confusion around the appropriate business models

for the new services. By examining FMC industry

from multiple perspectives from various players of

the value web as well as researchers of dissimilar

background, it is possible to bridge the gaps found in

various definitions in order to reach a common

understanding. Based on these evolutionary

pathways, players in the FMC industry must work

together to deliver services to end users. Model

shown in Figure 8 was developed to depict how the

stakeholders can collaborate to deliver FMC

services.

General

Service

Personalised

(Passive)

Personalising

(Active)

Intelligent

Intelligent

Voice

oriented

Voice oriented

Low speed

data

Multimedia

Fast,

broadband

multimedia

Mobile

Person

-to-

person

Person-to-

machines

Convergence

environment

SMS

Video streaming,

location-based

services, telematics

Image phone,

mobile TV

Cyberspace service,

remote treatment,

sensing, video

conferencing, high

capacity telematics

WEBIST 2006 - SOCIETY, E-BUSINESS AND E-GOVERNMENT

56

Figure 8: FMC Stakeholders’ Map.

5 DEPLOYMENT OF

CONVERGENT SERVICES

In South East Asia, SingTel (Singapore) introduced

three new and innovative services that would benefit

fixed-line, mobile phone and Internet users. The

services are OneM@il and Single Number Service.

Service trials for OneM@il had rolled out in July

1999 (SingTel, 1999). The commercial launch of

these services followed in 2000 (SingTel, 1999).

SingTel is offering these convergent services to

bring mobility and convenience to customers who

will be enjoy the benefits of integrated

telecommunications, IT and Internet capabilities

(SingTel, 1999). SingTel’s OneM@il service makes

message retrieval easier, faster and without hassle

(SingTel, 1999). All voice mail messages (whether

to a fixed-line or mobile phone); e-mails and faxes

are integrated in one mailbox and can be retrieved

from fixed-line telephones, mobile phones or

personal computers. OneM@il is equipped with a

sophisticated text-to-speech conversion engine

which ‘reads’ messages (SingTel, 1999). This means

that users of the service do not need a PC to retrieve

their e-mail. They simply access their OneM@il

mailbox to listen to a voice recording. The service

enables users to link multiple e-mail accounts. All

users are given a virtual fax number. Fax messages

can either be printed on any fax machine or read

from the Internet (SingTel, 1999).

On top of these, to expand its current offering of

Fixed Mobile Integrated (FMI) services, SingTel

announced the launch of a Single Number Service to

benefit its fixed-line customers. FMI refers to the

seamless integration of the fixed-line, mobile phone

and paging networks (SingTel, 1999). Such services

are currently available for mobile and paging

customers and SingTel aimed to extend it to fixed-

line customers as well (SingTel, 1999).

Network

Equipment

Vendor

Device

Manufacturer

Enabling

Technology

Vendor

Technology

Wireless

Network

Operator

Network

Business

Users

Users

End Users

Service

Provider

Payment

Service

Provider

Portal

Services

Content

Provider &

Aggregator

Products and

Services

Revenue

Communication Capabilities

Mobile

Network

Operator

Devices and Equipment

Communication Capabilities

Devices

Content and Applications

Devices and Equipment

1

Legend:

1. Network Access

2. Components, OS, Browsers, etc.

3. Content

4. Billing and Payment

22

3

43

4

BUSINESS MODEL ANALYSIS OF SEAMLESS ACCESS IN SOUTH EAST ASIA

57

In Malaysia, Maxis’ Wireless Office Solutions

(BlackBerry) satisfies customers’ data and voice

needs via a single, integrated handheld solution.

Customers now have access to a broad range of

applications which include e-mail, phone, intranet,

Internet, SMS and personal information

management applications operating over Maxis’

GSM and GPRS network (Maxis, 2005). BlackBerry

from Maxis boasts ‘push’ technology, which

automatically routes all e-mails straight to user’s

handheld (Maxis, 2005).

6 CONCLUSIONS

The FMC revolution is changing the way people live

and work. Mobile devices are already pervasive in

all major developed economies and in an increasing

number of developing ones as well. The study

presents a number of business models in order to

examine FMC industry from multiple perspectives.

In this manner it is possible to deal with foreseeable

convergence of the various mobile technologies. A

stakeholders’ map is developed to depict how

players in the FMC industry can collaborate to

deploy services. It is implicit throughout the study

that proper understanding of the FMC industry

enables players in the value web to adopt

appropriate business models in South East Asia to

bring services to market and how they should

cooperate, share revenue and jointly create

competitive advantages.

REFERENCES

Andreou, A. S., Chrysostomou, C., Leonidou, C.,

Mavromoustakos, S., Pitsillides, A., Samaras, G., et al.

2002. Mobile Commerce Applications and Services: A

Design and Development Approach.

Camponovo, G. 2002. Mobile Commerce Business

Models.

Camponovo, G., & Pigneur, Y. 2003. Business Model

Analysis Applied to Mobile Business. In 5

th

International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems., France.

Costello, M., & Knott, M. 2005. Customer Needs Should

Drive Fixed-Mobile Convergence Strategies.

Retrieved November 14, from

http://www.accenture.com/xd/xd.asp?it=enweb&xd=in

dustries%5Ccommunications%5Caccess%5Cbr34.xml

IDC. 2003. mCommerce: Where Are We Today? Kuala

Lumpur: IDC Market Research (M) Sdn. Bhd.

Lallana, E. C. 2003. Digital Review for Asia Pacific

2003/2004: Philippines.

Lee, J.-H., & Han, E.-S. 2005. Convergence Service of

Fixed and Mobile Network: Electronics and

Telecommunications Research Institute.

Lee, T. T. 2002, May 31. Stirring Up A Hive of Mobile

Activity. Computerworld Malaysia, 2, 1-3.

Lin, Y. B., & Chlamtac, I. 2001. Wireless and Mobile

Network Architectures. John Wiley & Sons. USA.

Maxis. 2005. Business in Real Time, All The Time - with

BlackBerry from Maxis. Retrieved November 25, from

http://www.maxis.com.my/business/LMC/index.asp

MCMC. 2005a. Cellular Phone Subscribers. Malaysian

Communications and Multimedia Commission. Kuala

Lumpur.

MCMC. 2005b. Communications & Multimedia: Selected

Facts & Figures. Malaysian Communications and

Multimedia Commission. Kuala Lumpur.

Nokia. 1999. The Demand for Mobile Value-Added

Services: Study of Smart Messaging: NOKIA.

Ollila, M., Kronzell, M., Bakos, M., & Weisner, F. 2003.

Mobile Entertainment Industry and Culture: Barriers

and Drivers. MGAIN. UK.

Porter, M. 1980. Competitive Strategy: The Free Press.

Schiller, J. 2000. Mobile Communications. Pearson

Education Limited. UK.

SingTel. 1999. SingTel Announces New ‘Convergent’

Services. Retrieved November 25, 2005, from

http://home.singtel.com/news_centre/news_releases/19

99-06-18a.asp

Swift, D., & Wilson, B. 2004, October 21. Fixed-mobile

Convergence Lands in Asia. Wireless Asia.

Travish, L., & Smorodinsky, R. 2002. Creating a Killer

M-Entertainment Service: Universal Mobile

Entertainment & Cash-U Mobile Technologies.

WEBIST 2006 - SOCIETY, E-BUSINESS AND E-GOVERNMENT

58