THE CONCEPTUALISATION AND ANALYSIS OF A

VALUE NETWORK

How to Create Value with Inter Organizational Communities of Practice?

Cláudia Fernandes, Luís Rocha

Technological Center for the Metal Working Industry – CATIM, Rua dos Plátanos, 197, 4100-414 Porto, Portugal

Keywords: Communities of Practice, Value Networks, Collaborative Learning, Knowledge Management, Value

Creation, Innovation.

Abstract: This paper will discuss how an ongoing experience on collaborative learning in the industry field that aligns

with the principles of a community of practice and how technology is used to support the learning and

development processes. It is a conceptual analysis that is grounded on theoretical frames and that will

provide the audience with opportunities to further reflect on learning communities. The authors present the

main results and experiences from the use of knowledge networks. They start by comparing the community

with pre-existing models, e.g. “Communities of Practice (CoP)” (Wenger & Snyder, 2000) and “Knowledge

networks” (Büchel & Raub, 2002). The work is based on one on-going experience in the industry/services

field, directly with Portuguese Technical Commissions (PTC), and it has several outputs such as new norms

and directives elaboration, norm projects voting, working papers, norms translation (quality system), etc.

There are over 204 persons involved in the 8 PTC managed by Technological Centre for the Metal Working

Industry (CATIM) from several different organizations, technological centres, institutes, and universities.

The final result is the value creation between the participants that sometimes enables practice rethinking and

innovative processes. With the discussion of the experience we aim to contribute to further reflection and

analysis of this emerging reality.

1 INTRODUCTION

Communities, networks, teams… are some of the

names given to groups of individuals working

together. CoPs, most likely, were the typical way to

learn before the “formal teaching system”. As we

look back in history we can find several examples,

and ask ourselves if the rupestral pictures weren’t

less an “art form” and more one visual

representation of tacit knowledge required for

hunting (Silva, 2005). We can firmly say that CoPs

always existed along with ways for representing

knowledge and learning practices, and have been of

great importance in the social learning process (e.g.

the learning of a new profession and/or task). These

methods for learning can be viewed along with

Schon’ “reflective practice” (Schon, 1982) where

learning is preformed and accompanied by one

master/specialist/monitor in one collaborative

setting, and it’s done in phases.

The technology’ social importance has been

seriously acknowledged by practitioners “in most

fields they will consist on geographically separated

members, sometimes grouped in small clusters and

sometimes working individually. They will be

communities not of common location, but of

common interest…” (Lickider & Taylor, quoted by

Andrade, 2005, p. 11) or even expertise (Dvorak,

2005).

CoP, in our days, is almost like a buzzword.

Everyone is asking, “How can I create a CoP?”

“How can I implement a CoP?”. In Portugal, and all

over the world the teaching and training systems

hardly have the capability to respond to

organizational demands. Organizations want their

co-workers to compete in innovative settings so they

can survive shifting in one global economy. Human

capital and organizational knowledge are the key

words to organizational performance and survivor.

The concept of CoP has been described as

“groups of people informally bounded together by

shared expertise and passion for a joint enterprise”

(Wenger & Snyder, 2000, p. 139). Some principles

are suggested to generate dynamics in CoP: trust,

collaboration, participation, communication, life

88

Fernandes C. and Rocha L. (2006).

THE CONCEPTUALISATION AND ANALYSIS OF A VALUE NETWORK - How to Create Value with Inter Organizational Communities of Practice?.

In Proceedings of WEBIST 2006 - Second International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies - Society, e-Business and

e-Government / e-Learning, pages 88-92

DOI: 10.5220/0001248900880092

Copyright

c

SciTePress

span and leadership. The challenge is in balancing

the belongingness and conflicts in emerging or

ongoing CoP.

According to some authors this definition

neglects the organizational support that networks

can benefit from the value that they can contribute to

the organization and not only the individuals

(Büchel & Raub, 2002).

Based on a study of 16 known organizations,

Büchel and Raub (2002, p. 589) proposed

knowledge networks of four types according to:

networks that primarily focus on individual benefits

vs those that focus on organizational benefits; and

networks that are self managed vs those that are

supported by managers. The proposed networks are:

1. Hobby Networks are based on individual

interests (e.g. travelling, tennis, etc) and usually

do not receive managerial support. Conform to

the traditional concept of CoP of Wenger and

Snyder.

2. Professional Networks extend beyond hobbies

by contributing to the building of individual

skills base. Like hobby, also professional

networks are according the traditional concept

of CoP of Wenger and Snyder. Knowledge

transfer in these networks is spontaneous and

ongoing, a natural by-product of work and

mutual support.

3. Best-practices Networks are essentially

institutional forms of knowledge sharing in

organizations, in a multi-directional way, each

member and each unit can, in principle, learn

from all the others.

4. Business Opportunities Networks are

business-driven, entrepreneurial networks,

which are potentially the most innovative and

attractive from a growth and development

perspective.

As we have exposed above the importance of

CoP and Knowledge Networks is recognized

worldwide, but there are several questions (e.g. Chae

et al, 2005) around the best way to build them.

According to Büchel and Raub (2002) there are four

stages for building knowledge networks:

1. Focusing the knowledge network. This is a

new concept (“Knowledge network”) that can

be viewed with some suspicion, so it has to be

aligned with the organizational strategic

priorities, and the bondages are around these

same priorities. There is a direct link between

the focus of a network and its ability to obtain

management support. In this stage links are

created to support the network.

2. Creating the knowledge network context. In

most cases networks form around a parallel

structure that exists alongside the more

traditional boundaries of functional

departments, product groups, business units, etc.

It’s very important to choose appropriate

communication mechanisms and fostering trust.

3. Routinizing network activities. Sometimes

there are loosen or non-links between the

members of a network, a certain amount of

routinization is an important step though

effective exchange and continued engagement

of the members. In these phase is established

the network “heartbeat” and it’s also very

important to define roles for each one of the

members. As in other groups, networks require

a set of differentiated roles to be developed over

time. Some examples are: network coordinator,

network supporter, network editor and network

sponsor.

4. Leveraging network results. Results are very

important to sustain a network, along with

knowledge creation and transfer. There is a need

to demonstrate to the community outcomes.

2 CATIM’ KNOWLEDGE

NETWORKS

This technological center (CATIM) is a

Normalization Sector-based Organism (NSO) since

1987 and adopted a different methodology since

2004. The mission of a technological center is to

support the industry development.

This shift in the used methodology was

accelerated by a process’ evaluation and by an

investment in a Learning Management System

(LMS) and all the technological and human structure

underneath.

First of all, we will define some concepts, and

underline our study scope. A Technical Commission

(TC) is a group of people with common interests that

work on them according to some expected outputs,

it’s volunteer and non remunerated work. A NSO is

an organism that coordinates the work of a TC, it’s

volunteer and non remunerated work also. The

Portuguese Quality Institute (PQI) is the mediating

organism between the Portuguese Technical

Commissions (PTC) and other countries TC, and

also between PTC and NSO. CATIM is a Portuguese

NSO and it’s a member of some PTC. In this paper

we will explore the experience of one techonological

center - CATIM as a NSO with coordination

functions.

This technological center manages 8 TC, there

are 13 CATIM’ technicians actively evolved in the

network (some with participation in several TC) plus

4 with support activities. There are over 210

THE CONCEPTUALISATION AND ANALYSIS OF A VALUE NETWORK - How to Create Value with Inter

Organizational Communities of Practice?

89

elements in the several TC (mean of 26 elements for

TC). It were created as many networks as active TC.

There are, on average, 36 presential meetings/year

(data since 1987), this number was severely

decreased in 2004 for 21 presential meetings/year.

From 1987 until 2003 the information

dissemination was done through letter, fax and e-

mail, the contacts where mostly done via telephone,

and the voting and idea exchange via fax. That was

very laborious and implicated a lot of time, namely

in the information photocopying (e.g. some

documents with several pages) its expedition to all

the participants in the different TC, and also, the

gathering and management of all the send/received

documentation from PIQ and the TC’ members. In

these settings there are important economical and

organizational issues to take in account (time,

human resources, paper, toner, stamps, phones, etc.).

Due to this setting evaluation the process started to

be mediated by one LMS available in the Internet

since the beginning of the year 2004. This LMS is

accessible by everyone that is recognized as a TC’

member or as a TC’ management team member

(authentication mechanism). The information is

gathered on a specific “room” (specific TC room) in

the LMS. Presently, all the tasks and information

dissemination are done on-line, eventually there are

some information exchange through telephone. The

LMS allows document voting and sharing, it has

synchronous and asynchronous communication

mechanisms, such as chat rooms and discussion

forums, and in addition it has also a leisure place

where games and thematic discussion rooms are

available.

The voting process was simplified because of its

mediation by the technology, for example, statistics

and tasks to be done are automatically generated and

sent to all the TC’ members, the work can be done

from anywhere with access to the Internet. The LMS

allows the process to be confidential and

anonymous. This fact is of great importance due to

the increasing number of members (in the present

over 210) from different locations and of increase of

TC managed by CATIM.

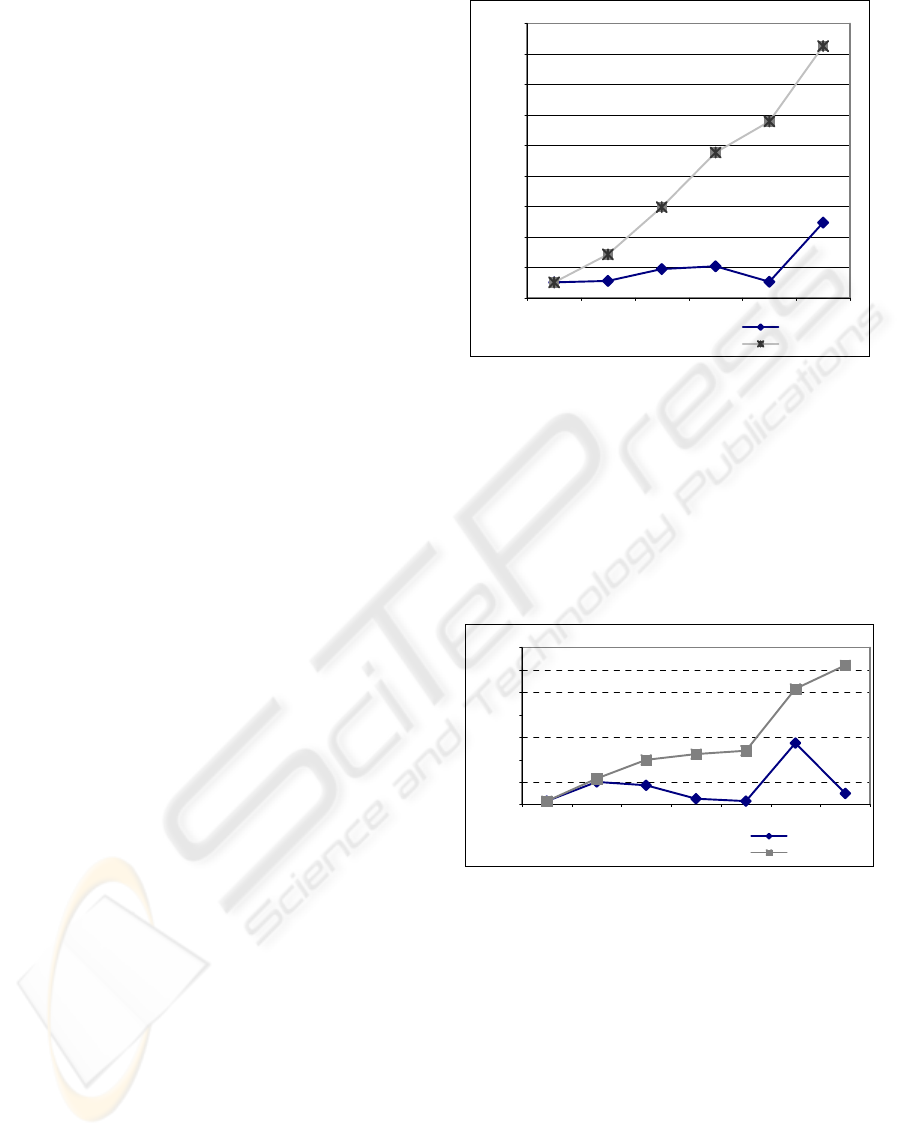

With figure 1 we try to illustrate the voting

processes over time, we see a rise of the activity

from 1996 to 1998 due to support of European

structural funds and also because of the natural work

cycles as we can see in the frequency curve. In 2004

there was a visible increase in the voting process,

this was owed to the internal re-organization of the

process, it’s mediation through the LMS and also, to

the work cycles.

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2004

Year

Normative documents voting

Frequency

Cumulative frequency

Figure 1: Document voting.

In figure 2 we have the number of finalized

documents, as direct outputs from the different PTC

and the volunteer work of over 210 persons from

different organizations. These documents were sent

to PQI and are now used by different organizations

(industrial and services), technological centres,

universities, and associations, among others, that

want to certificate their products and/or services.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2004

Year

Number of finalized document

s

Frequency

Cumulative frequency

Figure 2: Finalized documents.

The LMS has some available mechanisms not

yet used in these communities, such as chats rooms.

This is due to the nature of the work carried out,

although the exchanging documents’ and the voting’

areas are widely used.

2.1 CATIM’ TC Analysis

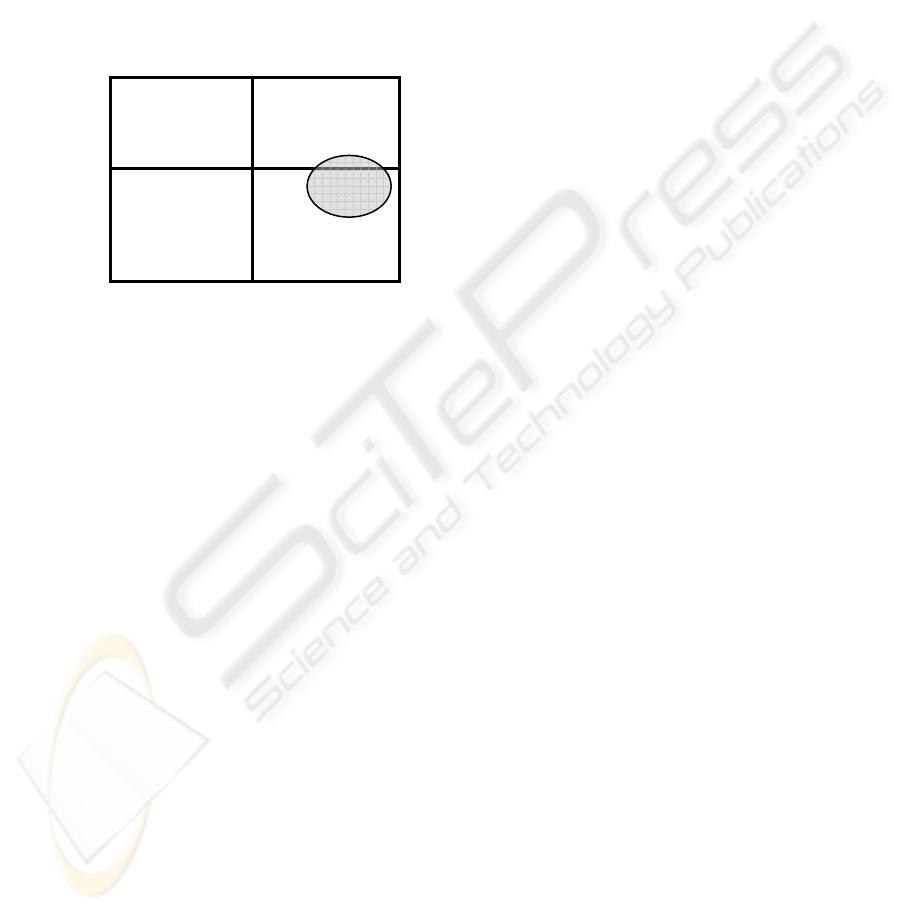

According to the Büchel and Raub model the TC

managed by this technological center, aligns in the

“business opportunity” network conceptualization,

which goes a little bit further than the traditional

Wenger and Snyder’ definition of CoP. It’s

presupposed the “creation of value”. In figure 3 we

WEBIST 2006 - SOCIETY, E-BUSINESS AND E-GOVERNMENT

90

can see that TC have great managerial support

although the individual support and participation are

clear to all. The benefit level is clearly

organizational, but all the participants have gains in

belonging to these networks/communities (TC).

They are basically driven by knowledge and

opportunity. The members have access to privileged

information and start to enlarge the personal and/or

organizational contact list, and get to know experts

in areas of common interest. The social capital is

one of the reasons that make people join a specific

network. In our case the LMS enhanced the

workflow and made the process easier and cheaper.

Supported

Managerial

“Professional

Learning” Network

“Best Practice”

Network

support

Self-managed

“Hobby”

Network

“Business

Opportunity”

Network

Individual Organizational

Benefit level

Figure 3: PTC integration according to the “Value

Network” model.

The group of individuals in PTC are genuinely

interested in creating new products (e.g. working

documents, Portuguese norms, working papers) that

can create new business opportunities and/or

products related to this new knowledge. These

outputs don’t necessarily fit in existing business

models. Unlocking this potential is one of the

intangible products of these networks that with time

can become tangible. Sometimes, in these settings,

rules are broken and new ones created, new

processes are created, and this strives the innovative

and creative processes.

As several studies (e.g. Karrisson et al, 2004;

Nerkar & Paruchuri, 2004) point up that most of the

knowledge used in the majority of companies is

developed externally. We can face this experience as

one example for a knowledge source.

3 CONCLUSION

The importance of knowledge networks is highly

recognized worldwide and in several areas, from

leisure to work. But as in other companies

worldwide, CATIM is learning with experience and

trying to get the best of it. One central concern is

how can we produce knowledge and get the best out

of the community? In our opinion, for fostering and

developing networks, one of the central issues is to

manage the context rather than little details. The

focusing on tangible results is one important setting

to “get the work done”.

Clearly the networks (TC managed by CATIM)

converged around knowledge and were based on

volunteer work, mainly virtually sustained through

an LMS (since 2004).

Its members took a proactive behaviour.

Participants used their existing skills and developed

new ones with the participation on these groups.

Several tangible outputs were achieved. This is

clearly the scenario that “1+1=3”, the group is

different from adding its parts, according to the

definition of a business opportunities network.

The used model can be partially replicated when

the following conditions are met:

1. The gains in belonging to the network are

individual but, mainly organizational;

2. The network has some managerial support;

3. The network is mediated by technology and

has technical support;

4. There are tangible results to be achieved (in

these particular case, norms, working papers,

working documents, norms’ translation,

discussion and voting, etc.);

5. The members have interest and gains by

belonging to the network (contact list, less

costs, work optimisation) and have the clear

conscience of that;

6. Contextual and economical variables, among

many others.

The technology opened new doors and enhanced

the learning and participation potential of singular

individuals in this mutual learning and production

process.

The organization ability to continuously

innovate and improve is clearly linked to the

capability of developing new skills based on (new or

renewed) knowledge. It’s the process of capability

building it self. And has we know increased

efficiency is a precondition to success. Belonging to

a knowledge network (or even to a CoP) is a

competitive advantage for the global economy.

REFERENCES

Andrade, A. (2005). Comunidades de prática – uma

perspectiva sistemica, Revista Nov@Formação,

Jun(5), 11-14.

Büchel, B. & Raub, S. (2002). Building knowledge –

creating value networks, European Management

Journal, 20(6), 587-596.

THE CONCEPTUALISATION AND ANALYSIS OF A VALUE NETWORK - How to Create Value with Inter

Organizational Communities of Practice?

91

Chae, B; Koch, H; Pardice, D. & Huy, V. (2005).

Exploring knowledge management using network

theories: questions, paradoxes and prospects, Journal

of Computer Information Systems, 45(4), 62-74.

Dvorak, P. (2005). Coping with the coming brain drain,

Machine Design, July(42), 36-42.

Karisson, C.; Flensburg, P. & Horte, S. (2004)(Eds)

Knowledge Spillovers and Knowledge Management,

1

st

Edition, London: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Nerkar, A. & Paruchuri, S. (2004) Evolution of R&D

capabilities: the role of networks within a firm,

Management Science, 51(5), 771-785.

Schon, D. (1982). The Reflective Practitioner – How

Professionals Think in Action, New York: Basic

Books.

Silva, A. (2005). Aprender através de comunidades de

prática, Revista Nov@Formação, Jun(5), 15-17.

Wenger, E. & Snyder, W. (2000). Communities of

practice: the organizational frontier, Harvard Business

Review, Jan-Fev, 139-145.

WEBIST 2006 - SOCIETY, E-BUSINESS AND E-GOVERNMENT

92