ELML, THE E-LESSON MARKUP LANGUAGE

Developing Sustainable e-Learning Content Using an Open Source

XML Framework

Joël Fisler

Geography Department, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland

Susanne Bleisch

Basel University of Applied Sciences (FHNW), 4132 Muttenz, Switzerland

Keywords: e-Learning, XML, open source, sustainable content, Internet, web, SCORM, IMS, education, eLML.

Abstract: eLML, the open source “eLesson Markup Language”, is an XML framework allowing authors of

e-Learning lessons to create structured and sustainable content. eLML is based on the pedagogical concept

ECLASS (adapted from Gerson, 2000), standing for entry, clarify, look, act, self-assessment and summary.

Each lesson is divided into units that contain a number of smaller learning objects. To allow different teach-

ing and learning scenarios most of the structure elements are optional or can be repeated several times and

in different orders. Lessons written with eLML can be transformed into HTML or PDF or be imported into a

learning management system (LMS) using the SCORM or IMS Content Packaging format. The paper pre-

sents experiences from the development of eLML itself, the design of e-Learning content based on the

eLML-structure, and the use of eLML-based content in conjunction with a LMS.

1 INTRODUCTION

eLML was developed

by the Swiss e-Learning

project GITTA (Fisler,

2004), a modular online

course in Geographic Information Science and

Technology. Within the GITTA project nearly forty

authors from ten partner universities created around

fifty lessons and ten case studies. The heterogeneous

and multilingual consortium needed strict pedagogi-

cal and technical guidelines to create consistent les-

sons with the same look and feel. After an extensive

evaluation of existing tools and learning manage-

ment systems (LMS) – back in 2001 most LMS used

proprietary formats and there have been many pro-

jects using such tools and losing their content after a

LMS’ development was discontinued due to the lack

of export possibilities – the project coordinators

agreed in 2001 to use XML for the technical imple-

mentation and base it on the pedagogical model

ECLASS (Gerson, 2000). Thus, the lessons can be

checked and validated for certain rules and restric-

tions by a XML Schema and therefore all authors

must create identically structured lessons.

The launch of eLML came only after the official

ending of the GITTA project when the Swiss Virtual

Campus discovered the potential of GITTA’s XML

structure. With minimal funding a consolidated,

server-independent and well-documented XML

framework based on XML Schema was developed in

spring 2004. This updated GITTA XML structure

was named eLML, the eLesson Markup Language

(Fisler et al., 2004) and was published as an open

source project under the General Public License

(GPL) on Sourceforge.net. Since then a constantly

growing number of projects and authors in Switzer-

land and Germany have started using eLML as their

tool for creating e-Learning lessons. At the Univer-

sity of Zurich and the University of Applied Sci-

ences Northwestern Switzerland eLML has become

the main XML framework for creating and maintain-

ing e-Learning content, a fact that ensures that fur-

ther funding and developing skills are put into the

enhancement of eLML.

180

Fisler J. and Bleisch S. (2006).

ELML, THE E-LESSON MARKUP LANGUAGE - Developing Sustainable e-Learning Content Using an Open Source XML Framework.

In Proceedings of WEBIST 2006 - Second International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies - Society, e-Business and

e-Government / e-Learning, pages 180-187

DOI: 10.5220/0001254701800187

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 PEDAGOGICAL CONCEPT

The aim of eLML was to offer authors a tool that

ensured conformity to pedagogical guidelines. These

guidelines were adapted from the ECLASS model

developed by Gerson (2000). ECLASS is an acro-

nym for the terms entry, clarify, look, act, self-

assessment and summary. Together with additional

important elements like glossary, bibliography and

metadata, the ECLASS elements build the main

structure of the XML framework eLML. The differ-

ent elements allow the creation of a pattern of learn-

ing experiences helping people to learn effectively

and efficiently (Horton, 2000).

As shown in Figure 1, lessons are organized into

different modules that again are part of a complexity

level. Levels and modules are purely organizational

entities with no technical relation within eLML. In

eLML, lessons are the smallest interchangeable enti-

ties. A lesson is built from units (conforming to the

ECLASS model) and of additional elements like

learning objectives, bibliography, glossary and

metadata.

Level (e.g. Basic Level)

Module (e.g. Systems)

Lesson (e.g. What is a GIS?)

Unit (e.g. General Introduction)

- Entry

- Clarify

- Look

- Act

- Self-assessment

- Summary

Figure 1: ECLASS model adapted from Gerson.

eLML is not as rigid as it may look. Since some

elements are optional (see Figure 2) or can be used

in reverse order, it is flexible enough to allow the

representation of different e-Learning scenarios such

as the following:

– Lessons: Standard e-Learning lessons begin with

an entry element that describes the context or the

content of the lesson. They could continue with a

clarify element explaining the theory and either

one or more look elements to show examples or

an act element where the students are invited to

try something by themselves. Usually lessons

end with a self-assessment to check if the learn-

ing objectives are reached and a summary.

– Case studies: As Niederhuber (2005) describes,

GITTA case studies use their own didactical

model but are nevertheless implemented in

eLML. They usually start with an entry element

followed by two units (using clarify elements),

where the clarify elements are used to describe

the instructions and not to explain theory.

– Other Forms: Another project uses eLML to

document and generate structured reports. In this

case, elements such as act and self-assessment

elements are not used. The GITTA project even

uses eLML to create its public website.

3 THE STRUCTURE OF ELML

The described pedagogical model ECLASS is

mapped onto an XML structure using XML Schema:

Figure 2: Top level structure of eLML.

An eLML lesson always starts with either the

mandatory introduction (element entry) or a concise

listing of the lessons learning objectives (element

goals). The unit elements, described below, contain

the actual content of a lesson. Following the units a

lesson can have a summary and/or up to five self-

assessments followed by an optional further reading

and glossary section to list important resources and

to describe terms used within the lesson. The XML

Schema ensures that all glossary terms used in a

lesson are defined in the glossary. The APA (2005)

or the Harvard Citing System (Holland, 2004) can be

used for the bibliography. All citations, references,

further readings etc., have to be listed within the

bibliography section, otherwise the XML parser is-

sues an error and the lesson will not be valid.

Using mandatory elements eLML ensures that at

least the minimal metadata elements are filled out

even though many authors do not like to fill in

metadata information. The eLML metadata elements

ELML, THE E-LESSON MARKUP LANGUAGE - Developing Sustainable e-Learning Content Using an Open Source

XML Framework

181

are a subset of the IMS LOM “Learning Resource

Metadata Specification” (2002) and can be used to

store data about the length of the lessons, the au-

thor(s), copyrights, the required knowledge to work

through the lesson and the basic technical require-

ments. The bibliography style elements and the

metadata section are defined in a separate XML

Schema and thus can be replaced by other standards

or definitions.

Within each unit a similar structure as the one on

lesson level is employed. However, the elements

glossary, bibliography and metadata are always de-

fined for the whole lesson only and not repeated on

unit level. The actual content within a unit is stored

in a number of so-called “learning objects” (not to

be confused with the learning objectives, called

“goals” within eLML). Each learning object de-

scribes a certain concept, model, equation, term, or

process using the three elements clarify (theory),

look (example) and act in free order. These three

elements can have a special visual representation

when transformed into a presentation format – e.g. a

“gear” icon for act elements is used in GITTA to

signal to the student that they have to “do” some-

thing – but their main purpose is to guide authors

while creating content. Using the elements clarify,

look and act, the author has to think about how a

certain concept can be presented best to the student.

Whether a learning object starts with some theory

(clarify element) and continues with one or more

examples (look elements) or, alternatively, the stu-

dent first has to do something (act element) and then

reads the theory afterwards (clarify element) is left

to the author. Especially the element act should re-

mind the authors that effective learning is active

learning (Horton, 2000) and that exercises, projects

and other individual and group work should be in-

cluded into lessons. A learning object typically fits

on one or two screen pages and takes the student

about five to ten minutes to understand. But the total

length or required working time for a lesson is not

defined within eLML. Some projects use one eLML

lesson per two-hour classroom lesson; others repre-

sent a whole semester course in one lesson.

3.1 Structuring the Content

The last section covered the basic structure of an

eLML lesson. The mentioned structural elements,

entry, unit, learning object, self-assessment, sum-

mary etc., can be looked at as lesson chapter titles.

Within these chapters, there are content elements

that contain the actual text, multimedia elements,

and so on.

The old GITTA structure employed semantic

elements like, for example, explanation, remark or

motivation paragraphs. The authors rejected this

approach, as the usefulness of such elements was not

obvious. Additionally, most of those elements were

visually represented the same way when transformed

into a presentational format. If they were displayed

differently, then the authors selected the paragraphs

according to their final appearance and not because

of the semantic meaning. In theory, a total separa-

tion between content and representation (layout)

would be desirable but – as the GITTA project

showed within its three years – this is not realistic.

Therefore certain structural elements (column, for-

matted, newLine etc.) are offered within eLML to

meet the basic needs of the authors. The following

list describes the eLML content elements:

– column: Defines a two- or three-column layout.

– table: For tables and not as a layout element.

– list: Numbered or bulleted lists.

– box: Content is represented in a box. The exact

layout of boxes is defined in a separate CSS file.

– term: Using a glossary term the definition is ei-

ther appears as “mouse over” layer with a link to

the glossary or as a separate paragraph.

– newLine: A short or long line break.

– multimedia: Pictures, Flashes, Applets, Movies,

SVG or even plain HTML code (e.g. JavaScript).

– formatted: Possibility to format text as bold,

italic, underlined, subscript etc. or use CSS code.

– popup: Clicking on the question opens a box

with an answer.

– link: Link to external or internal resources in-

cluding other units, learning objects etc.

– citation: Can be inline or as a paragraph with

many options described in the manual. The cited

resource has to be defined in the bibliography!

– paragraph: Regular paragraph with attributes

like; being visible only to tutors, displayed only

in the print or online version of a lesson, etc.

– indexItem: Marks words to be listed in the index.

All of these elements have additional attributes

like role (tutor/student), visibility (online/print),

class (remark, important, etc.) and others parameters

described in detail in the manual. eLML also defines

rules for the nesting of elements. For instance, to

include a column within a list element would not

make sense, neither would a table within a multime-

dia element. Therefore the XML Schema exactly

defines which element can be used where.

3.2 Authoring Tools

Creating an eLML lesson typically starts with defin-

ing the learning objectives of a particular lesson (the

WEBIST 2006 - E-LEARNING

182

“goals” element). When the author has defined what

the student should learn from a lesson, they then

decide on the units that are needed to present the

subject matter and define learning objects that pre-

sent a certain aspect of the topic. The actual writing

of the lesson is usually done with an XML editor.

Multimedia elements like movies or flash anima-

tions etc. are made using the appropriate tools. To

facilitate the use of eLML for authors not familiar

with XML two promising solutions are in progress.

The University of Zurich is currently developing

an eLML authoring tool that will be integrated into a

content management system and allows simple edit-

ing of eLML lessons using a standard web browser.

This authoring tool should be available in late 2006.

Another solution is to use tools that can render a

Graphical User Interface (GUI) based on an XML

Schema like, for example, JAXFront (2001). It was

tested with eLML and is able to simplify the mainte-

nance of lessons enormously.

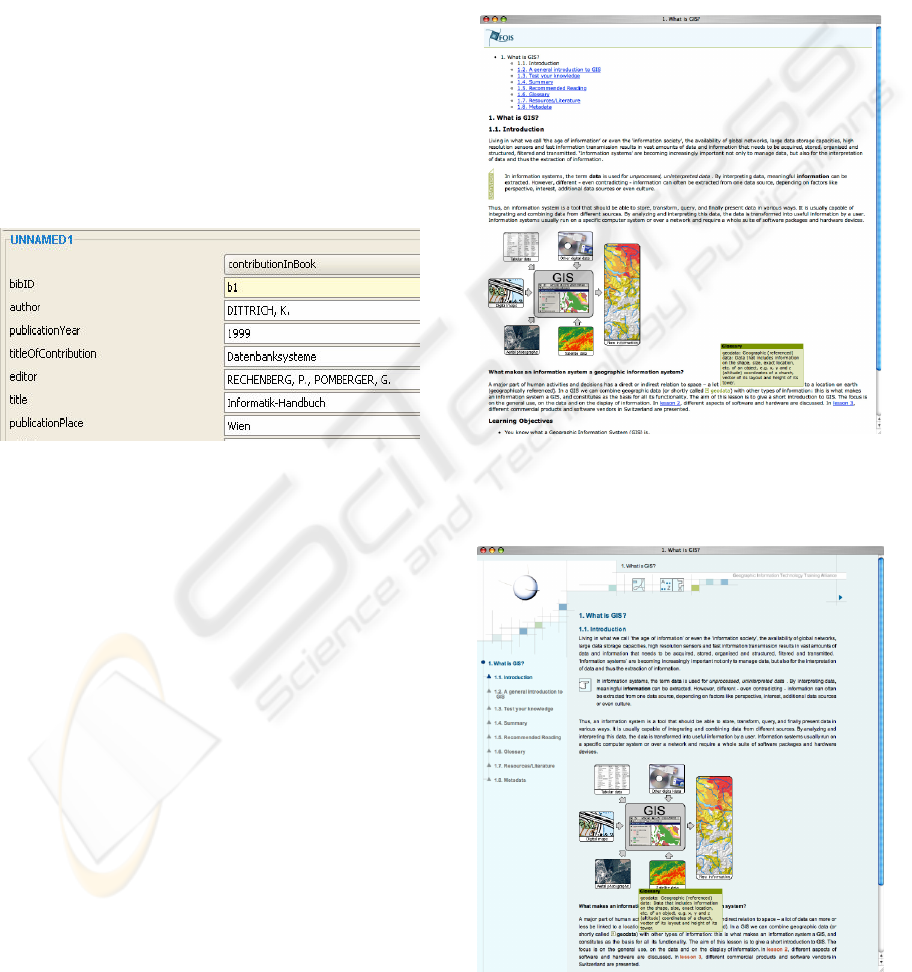

Figure 3: JAXFront renders a GUI based on an

XMLSchema.

4 PRESENTATION

eLML includes files for transformation of XML les-

sons into both an online (HTML) and a print (PDF)

version. A third output option for mobile devices

and PDAs is under construction. The following sec-

tions will cover the different formats supported by

eLML. This chapter also shows the advantage of

separating the presentation from the content, as it is

done with XML in general and therefore also with

eLML. While the content can be updated to reflect

the current knowledge about a subject, the presenta-

tion can be updated within seconds by simply re-

transforming the lessons. On the other hand it is pos-

sible to do the transformation of a lesson several

times with different transformation scripts and thus

get different output formats or styles.

4.1 Online (HTML)

The author of a lesson can choose between different

built-in layout templates or create their own tem-

plate. The standard transformation file of eLML

produces clean XHTML 1.0 code including many

CSS classes for boxes, tables, goals etc. The follow-

ing screenshot shows a lesson where the author only

adapted the according classes in the CSS file and did

not need any knowledge of HTML or XML at all:

Figure 4: Lesson presented using the FOIS project layout.

For knowledgeable authors it is possible to use

XHTML to create a more sophisticated layout like

the following example demonstrates:

Figure 5: Lesson presented using the GITTA layout.

ELML, THE E-LESSON MARKUP LANGUAGE - Developing Sustainable e-Learning Content Using an Open Source

XML Framework

183

Furthermore an author can decide if new

XHTML files should be created for each learning

object or if each unit should be displayed on one

page as a whole. This scenario is, for example, used

for case studies that do not contain as much text as

regular lessons. It is also possible to display the

whole lesson on one single page. The creation of

multiple pages is done by using XSLT 2.0 com-

mands; no parser specific elements have been used.

Therefore any XSLT 2.0 aware parsers support this

feature.

4.2 Online (SCORM & IMS CP)

eLML supports both Sharable Content Object Refer-

ence Model (SCORM, 2004) and IMS Content

Packaging (IMS CP, 2000) standards. Almost all

learning management systems (LMS) available to-

day like, for example, WebCT or OLAT, support

one of these standards and therefore are able to im-

port lessons created in eLML. The following exam-

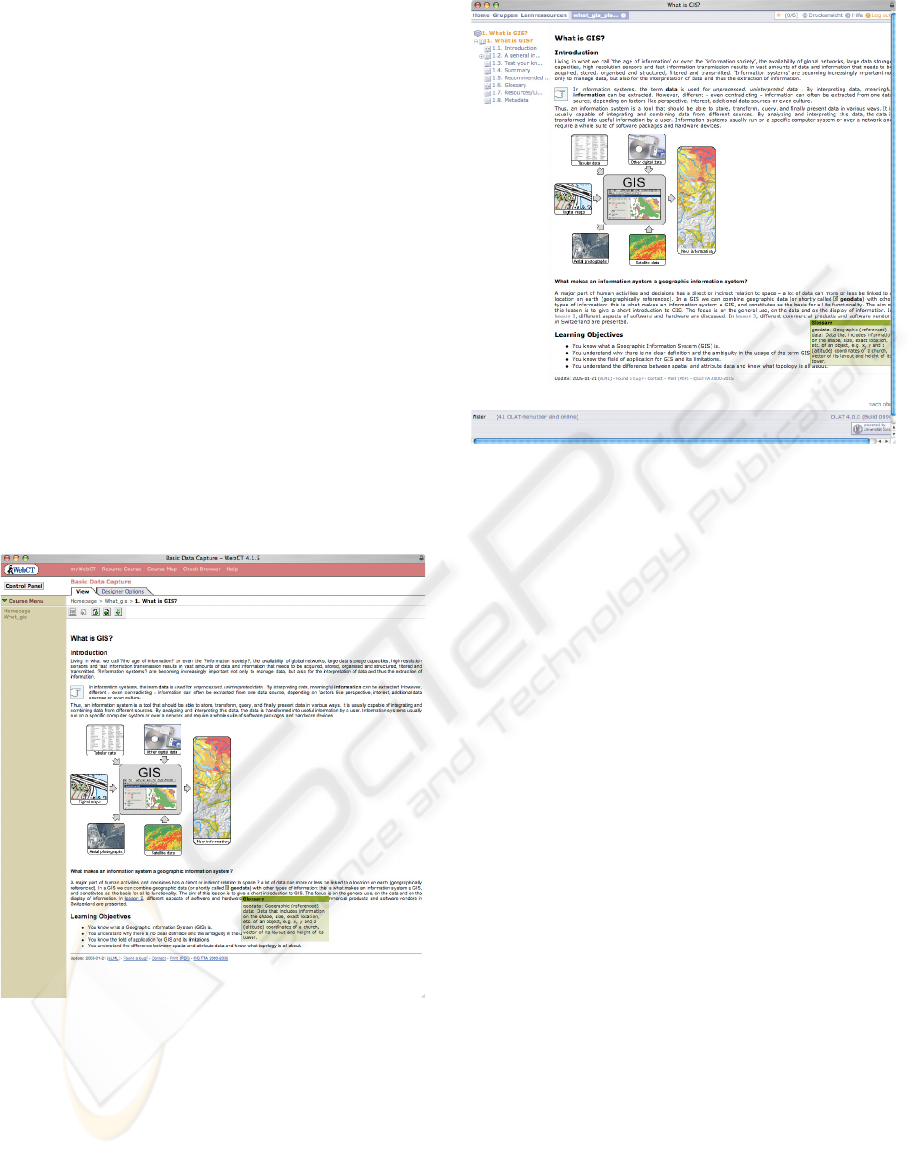

ple shows the same lesson as illustrated in the last

chapter but this time imported into WebCT using the

SCORM standard:

Figure 6: Lesson imported into WebCT using SCORM.

At the University of Zurich the main learning

management system is a self-developed open source

LMS called OLAT (1999) that supports the IMS

Content Package standard for importing of lessons.

The following screenshot shows a lesson imported

as an IMS Content Package into OLAT:

Figure 7: Lesson imported into OLAT using IMS CP.

These examples show how lessons developed us-

ing eLML can be fully integrated into any LMS sup-

porting the mentioned standards. It is important to

understand that both the SCORM and the IMS CP

standards do not define how the content itself is

structured but how the lesson as a whole is built up

and packed. So if a project decides to support one of

these standards, there is still the need to decide on

how the actual chapters of a lesson are built-up and

structured. That’s where eLML is filling an impor-

tant gap that neither standards, SCORM and IMS

CP, cover.

4.3 Print (PDF)

The print version uses the Apache Formatting Object

Processor (Apache FOP, 2001) to generate a PDF

document similar to the one shown in Figure 8. The

FOP itself is a freely available open source product

and already built into most available XML editors.

Additional eLML parameters can be adjusted that

impact on the final layout. These include header and

footer texts, disabling the chapter numbering, lan-

guage settings, etc. These options are described in

detail in the eLML manual.

WEBIST 2006 - E-LEARNING

184

Figure 8: Lesson transformed into a PDF document.

4.4 Mobile Devices/PDA

There is a special layout version for mobile devices

like PDAs etc. under construction. This layout will

display a lesson in a specially adapted way so it can

be viewed on small screens with low resolutions.

The final version will be published on the eLML

website as soon as it is finished.

5 COMPARING ELML TO

OTHER MARKUP

LANGUAGES

eLML must be understood as the result of three

years working experience with an XML-based

e-Learning content structure. It was once planned

and realized but then improved over the years

through author feedback and the practical experi-

ences with it. This fact makes eLML a very easy to

understand and user-friendly markup language. To-

day many different XML markup languages for

e-Learning content exist but back in 2001 when

GITTA started none of the existing structures satis-

fied the projects needs. They were either to complex

or they were not based on a pedagogical model. The

following comparison will give an overview about

the differences between existing markup languages

and eLML.

It is important not to confuse eLML with stan-

dards like SCORM or IMS Content Package. These

standards are both supported by eLML and are only

used for interoperability of content between different

learning management systems (LMS). They do not

describe the content itself. See chapter 4.2 for com-

patibility of eLML with both standards.

5.1 LMML – Learning Material

Markup Language Framework

LMML, the Learning Material Markup Language

Framework started in 1999 at the University of Pas-

sau (Süss, 2001). LMML is a modular language with

the possibility to create new objects as needed. The

LMML content objects use different semantic ob-

jects like motivation, definition, remark, example

etc. In theory a very interesting approach also used

by GITTA but then dropped in eLML due to prag-

matic reasons as described in chapter 3.1. eLML

now offers content objects like box, popup, table, list

etc. whose appearance can be defined separately

using CSS. But the concept of semantic distinction

of objects still remains as a special attribute called

"class" where the author has the possibility to define

classes like "remark", "important" or "motivation"

and highlight them in the layout. LMML offers a

simple XSLT file for transforming a lesson into

HTML (no other format supported) but does not

have any authoring tools available on the website.

The code has not been updated since nearly two

years therefore it is not clear if the founder Christian

Süss will continue this project or if LMML was only

meant as a dissertation project (see Süss, 2005) and

will not be updated anymore.

5.2 ML3 – Multidimensional

Learning Objects and Modular

Lectures Markup

A very similar markup language is ML3, the Multi-

dimensional Learning Objects and Modular Lectures

Markup Language developed at the University of

Rostock together with 12 partner institutes in Ger-

many (ML3, 2005). On the content level it works

with similar educational objects as LMML (e.g. de-

scription, remark or example) therefore it seems that

there has been cooperation between these Universi-

ties. However, ML3 is far more developed and still

maintained. It also now offers an authoring tool

based on FrameMaker.

The very brief website describes the concept of

dimensions that is used in ML3. Basically a lesson

can be described in three axes: Intensity (basic, ad-

vanced, expert), target (teacher or learner) and de-

ELML, THE E-LESSON MARKUP LANGUAGE - Developing Sustainable e-Learning Content Using an Open Source

XML Framework

185

vice (online, print or slide). An author, while writing

a lesson, can define if a paragraph or illustration is

used in the basic and/or advanced version, only on

slides, visible for teachers only etc. eLML offers a

similar separation by target (author and student ver-

sion of a lesson) and by device (online or print). In

ML3 these options lead to a total of 18 possibilities

to present a lesson, so it is important that the author

does not loose track about what is shown in which

version and what not.

ML3 also offers the possibility to include and re-

use objects in different lessons. Therefore bibliogra-

phy and glossary data are stored in a database and

the same resource can be used in different lessons.

This is in theory a nice approach that has also been

used in GITTA, but was dropped in eLML. The

main reason was that one author would not accept a

definition of a certain term done by another author

from another institute. The authors usually want

their definition to appear in their lesson. So in reality

the reusability was not used at all. There were also

technical reasons for dropping this feature: Main-

taining a database is a lot more complicated than

storing the content directly within the XML file.

Furthermore validation (did the author really define

the term? did he list the cited book in the bibliogra-

phy? etc.) within the XML editor is only possible if

the content is stored within the XML file. There

were also practical reasons for dropping database

bindings: Lessons in plain XML files can be trans-

formed with every standard XML editor using stan-

dard XSLT 2.0 processors.

ML3 offers many possibilities to define self-

assessments: multiple choice, yes-no questions, es-

say etc. eLML did not implement these options at all

because we believe that tests usually need user-

tracking and therefore should be implemented within

an LMS. If not implemented directly in the LMS, it

is not possible to store students’ test-results and

grades and therefore eLML only offers basic support

for self-assessments.

To conclude, ML3 seems an interesting approach

and it will be interesting to see the development of

this markup language.

5.3 IMS Learning Design & EML

The Open University of the Netherlands developed

EML, the Educational Modelling Language, which

was then overtaken by the IMS consortium and is

now called the IMS Learning Design Specification.

This markup language is based on many different

behaviouristic, cognitive and constructivist ap-

proaches to learning and instructing. It concentrates

on the teaching-learning process using different

roles, activities etc. around e-Learning. The actual

content is stored in HTML and therefore this markup

language cannot be compared with eLML. In theory

it should be possible to use the IMS LD specification

for describing an e-Learning module and within that

module use eLML to describe the content, but this

has not been tested yet.

Other XML markup languages exist and they all

have their advantages and disadvantages. In the end

the decision for a specific language is mostly made

because of personal contacts to other users or au-

thors. Additionally, using XSLT allows the trans-

formation of a lesson from one XML format into

another XML format. Therefore if sustainability is a

major concern it is not too important which specific

XML markup language is used but that XML is used

at all. Because, unlike HTML where layout and con-

tent is mixed, XML offers the possibility to really

separate content from presentation. A major concern

when it comes to sustainability.

6 EXPERIENCES

Compared to other markup languages eLML has a

very pragmatic approach and an easy to learn struc-

ture using descriptive tag names. Authors experi-

enced with XML need less than half a day of train-

ing to be able to work with eLML. On the other

hand, the lack of WYSIWY authoring tools makes

eLML a rather difficult to learn markup language for

authors who never worked with XML. The planned

authoring tool due for summer 2006 will hopefully

fill this gap.

The very rigid GITTA XML structure (the ances-

tor of eLML) was loosened with the release of

eLML 1.0 and even more flexible with eLML 2.0.

Therefore, eLML can be used for different learning

scenarios as described in detail in chapter 2. On the

other hand, there is a constant dilemma between

having a structure strict enough to conform to a cer-

tain pedagogical model and the freedom authors

want while designing lessons. With eLML we found

a rather pragmatic approach to solve this problem.

The growing number of authors working with

eLML pushes the development and leads to new

features and new formats supported. Creating such

an “eLML community” was the main idea when

releasing the eLML as an open source framework. A

lot of time and money can be saved if many projects

work together using the same technical structure

instead of each project having to start from scratch.

WEBIST 2006 - E-LEARNING

186

7 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

eLML is a proven and tested approach for the crea-

tion of sustainable e-Learning content and it is also a

strictly defined XML language. XML has the advan-

tage of structuring and labelling content. As a stu-

dent, in future it will be crucial to be able to find and

use different e-Learning resources like, for example,

the eLML-based GITTA lessons (Fisler, 2004) on

the World Wide Web. The Semantic Web efforts

provide promising technologies for e-Learning (Sto-

janovic et al, 2002). By supporting SCORM and

IMS Content Packages eLML goes in the right di-

rection. Research results how these SCORM Meta-

data can be integrated for e-Learning purposes are

presented by Qu (2004).

ACKNOLEDGEMENTS

The work reported in this paper has been supported

by the Swiss Virtual Campus (SVC) program under

project no. 2001-28 and 2004-32, as well as by con-

tributions of the University of Zurich (E-Learning

Center), and of the ETHZ FILEP fund. These con-

tributions are gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

URLs listed below were last accessed on February 7

th

06!

APA, 2005. The APA Style. American Psychological Assn.

Website, Washington DC. http://www.apastyle.org/

Apache FOP, 2001. Formatting Object Processor. Version

0.20.5. http://xml.apache.org/fop/

Fisler, Joël, 2004. GITTA website. Geography Department,

University of Zurich. http://www.gitta.info

Fisler, Joël, Bleisch, Susanne, Niederhuber, Monika, 2005.

Development of sustainable e-Learning content with

the open source eLesson Markup Language eLML.

In: ISPRS Workshop, Potsdam, June 2./3. 2005.

Gerson, S., 2000. ECLASS: Creating a Guide to Online

Course Development For Distance Learning Faculty.

Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration,

Vol. III, No. IV (Winter 2000). State University of

Western Georgia. http://www.westga.edu/

~distance/ojdla/winter34/gerson34.html

Holland, Matt, 2004. Citing References: Harvard System.

Bournemouth University. www.bournemouth.ac.uk-

/library/using/harvard_system.html

Horton, William, 2000. Designing Web-Based Training,

Wiley, New York.

IMS CP, 2000. Content Packaging Specification. IMS

Global Learning Consortium, Inc.

http://www.imsglobal.org/content/packaging/

IMS LOM, 2002. Learning Resource Metadata Specifica-

tion. IMS Global Learning Consortium, Inc.

http://www.imsglobal.org/metadata/

JAXFront, 2001. JAXFront - an XML Rendering Technol-

ogy. Xcentric GmbH, Zürich, Switzerland.

http://www.jaxfront.com/

ML3, 2005. Multidimensional Learning Objects and

Modular Lectures Markup Language website.

http://www.ml-3.org

Niederhuber, M., Heinimann, H. R., Hebel, B., 2005.

e-Learning basierte Fallstudien zur akademischen

Ausbildung in der Geoinformatik: Methodisches

Konzept, Umsetzung und Erfahrungen. Submitted to

the 3. Deutsche e-Learning Fachtagung Informatik,

13.-16. September 2005 in Rostock.

OLAT, 1999. Open Source LMS OLAT - Online Learning

And Training. Multimedia & E-Learning Services

(MELS) der Universität Zürich. http://www.olat.org/

SCORM, 2004. Sharable Content Object Reference

Model. Advanced Distributed Learning.

http://www.adlnet.org

Stojanovic, Ljiljana, Staab, Steffen, Studer, Rudi, 2002.

e-Learning based on the SemanticWeb,

http://lufgi9.informatik.rwth-

aachen.de/lehre/ws02/semDidDesign/lit/SemanticWeb

ELearning.pdf

Süss, Christian, Freitag, Burkhard, 2001. LMML Learning

Material Markup Language. IFIS Report 2001/03.

Süss, Christian, 2005. Eine Architektur für die

Wiederverwendung und Adaptation von e-Learning-

Inhalten, PhD-Thesis, University of Passau.

Qu, Changtao, Nejdl, Wolfgang, 2004. Integrating

XQuery-enabled SCORM XML Metadata Repositories

into an RDF-based E-Learning P2P Network.

Educational Technology & Society, 7 (2), 51-60.

To stay informed about eLML, visit

www.elml.ch or subscribe to the eLML Newsletter

by sending an email with the subject “subscribe” to

eLML-news-request@lists.sourceforge.net.

ELML, THE E-LESSON MARKUP LANGUAGE - Developing Sustainable e-Learning Content Using an Open Source

XML Framework

187