MEDICAL INFORMATION PORTALS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY

OF PERSONALIZED SEARCH MECHANISMS AND SEARCH

INTERFACES

Andrea Andrenucci

Department of Computer and System Sciences, Stockholm University/ Royal Institute of Technology,

Forum 100, SE-16440, Kista, Sweden

Keywords: Internet HCI, User Modelling, Information Retrieval, User Needs.

Abstract: The World Wide Web has become, since its creation, one of most popular tools for accessing and

distributing medical information. The purpose of this paper is to provide indications about how users search

for health-related information and how medical portals should be implemented to fit users’ needs. The

results are mainly based on the evaluation of a prototype that tailors the retrieval of documents from the

Web4health portal to users’ characteristics and information needs with the help of a user model. The

evaluation is conducted through a user empirical study based on user observation and in-depth interviews.

1 INTRODUCTION

The World Wide Web has become, since its

creation, one of most popular tools for accessing and

distributing medical information (Eysenbach, Sa &

Diepgen, 1999). However Web-mediated medical

portals are rather limited since their search engines

do not allow for personalized searching facilities and

deliver the same generic medical information to all

users (Moon & Burstein, 2005).

The purpose of this paper is to provide

indications about how users search for health-related

information and how medical portals should be

implemented to fit users’ needs at best. The

indications cover search mechanisms, content

presentation and search interfaces. The results are

mainly based on the evaluation of a prototype that

tailors the retrieval of documents from the

Web4health portal to users’ characteristics and

information needs with the help of a user model

(UM). The evaluation is conducted through a user

empirical study based on user observation and in-

depth interviews. This study is, to our knowledge,

the first observational study carried out to

investigate the retrieval strategies of people

searching for health information on a medical portal

where different techniques for personalized search

were implemented. Since most of studies covering

Information Retrieval (IR) systems implementing

personalized search either focus on evaluating the

quality of the retrieved information (Boyle &

Encarnacion, 1994) or the interaction with the user

interface (Brajnik, Mizzaro & Tasso, 1996), we try

to evaluate both those aspects with the help of users’

point of view.

The paper is structured as follows: section two

describes related research in the fields of user

modelling, information retrieval and medicine.

Section three describes the portal and the prototype

utilized in this research. Section four and five

present the empirical study and its results. The paper

is concluded with a discussion (section six) and the

paper conclusions (section seven).

2 UM IN IR AND MEDICINE

Information retrieval (IR) and Information filtering

(IF) are two of the research areas where UM

techniques have been used most frequently. The

corpus can be limited to a certain information

domain or open to the entire Web. Among the most

recent systems belonging to the first group it is

worth mentioning Kavanah (Santos et al., 2003).

Kavanah provides search assistance in matters of

health and medical information. User queries are

dynamically changed or constructed considering not

only the user input but also information covering the

user preferences, knowledge and interests. This

95

Andrenucci A. (2006).

MEDICAL INFORMATION PORTALS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF PERSONALIZED SEARCH MECHANISMS AND SEARCH INTERFACES.

In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - HCI, pages 95-102

DOI: 10.5220/0002486900950102

Copyright

c

SciTePress

information is explicitly encoded through an

ontology network that is constantly updated.

The WIFS system (Micarelli & Sciarrone, 2004)

is an IR system that retrieves information from the

Web’s open corpus. It uses a sophisticated user

model to adaptively filter and sort search results

returned by the AltaVista search engine. WIFS uses

explicit user ranking of search results to keep the

user model updated.

One of the most popular areas for usage of UM

techniques in health applications is patient education

(Lyons et al., 1982), i.e. services aimed to supply

people without medical expertise with specific

information in order to make them understand their

situation better and reduce costs in health care.

Patient education has been utilized in matters of

smoking cessation (Lennox et al., 2001), eating

habits improvement (Grasso, Cawsey & Jones,

2000), and management of illnesses such as cancer

(Bental et al., 2000).

3 THE PORTAL AND THE

PROTOTYPE

The medical portal utilized in this research

(Web4health.info) is well established among the

medical portals on the Web. It is Yahoo-listed and it

was developed within a EU-financed project called

KOM 2002 (http://web4health.info/KOM2002),

whose goal is to provide multilingual medical

information to improve the mental health of

European citizens. Psychiatrists and

psychotherapists from five different European

countries (Italy, Sweden, Holland, Greece and

Germany) use the portal to jointly develop a set of

semantically classified Web pages that answer

questions in matters of psychological and

psychotherapeutic advice. Users consult the

knowledge base submitting questions in natural

language, which are then matched against pre-stored

FAQ-files (Frequently Asked Questions) consisting

of question/answer pairs, where the question part has

a template created to match many different

variations of the same question (Template-Based

Question Answering, Sneiders 2002).

The user model in the prototype is based both on

an explicit and an implicit acquisition of knowledge

about the user (Kass & Finin, 1998). The practical

implementation of the profiling mechanisms is done

through a dialogue to be held at the beginning of the

interaction process, where the user can choose

between two options: either explicitly stating the

topics of personal interest (Direct Choice, DC), with

the help of a menu-based rating form, or implicitly

providing them (Indirect Choice, IC), letting the

system infer his/her interests by monitoring the

interaction with the system. Through the form, users

choose specific diseases, select up to three

categories of interest in the knowledge domain,

ranking them in order of relevance (1 as the most

relevant, 3 as the least relevant) and select the

objective of their search. Through the Indirect

Choice, the system learns from observation, i.e. it

monitors the questions submitted by the user and the

topics of the answers retrieved by the Question

Answering (QA) system in order to learn about the

interests and the objectives of the user. The system

computes the topics and the objectives that occur

more often among user questions and the retrieved

documents, and ranks them in descending order. The

three most occurring categories, diseases and search

objectives are then presented to users on a feedback

panel. Users can then discard, confirm partly or in its

entirety the inferred profile.

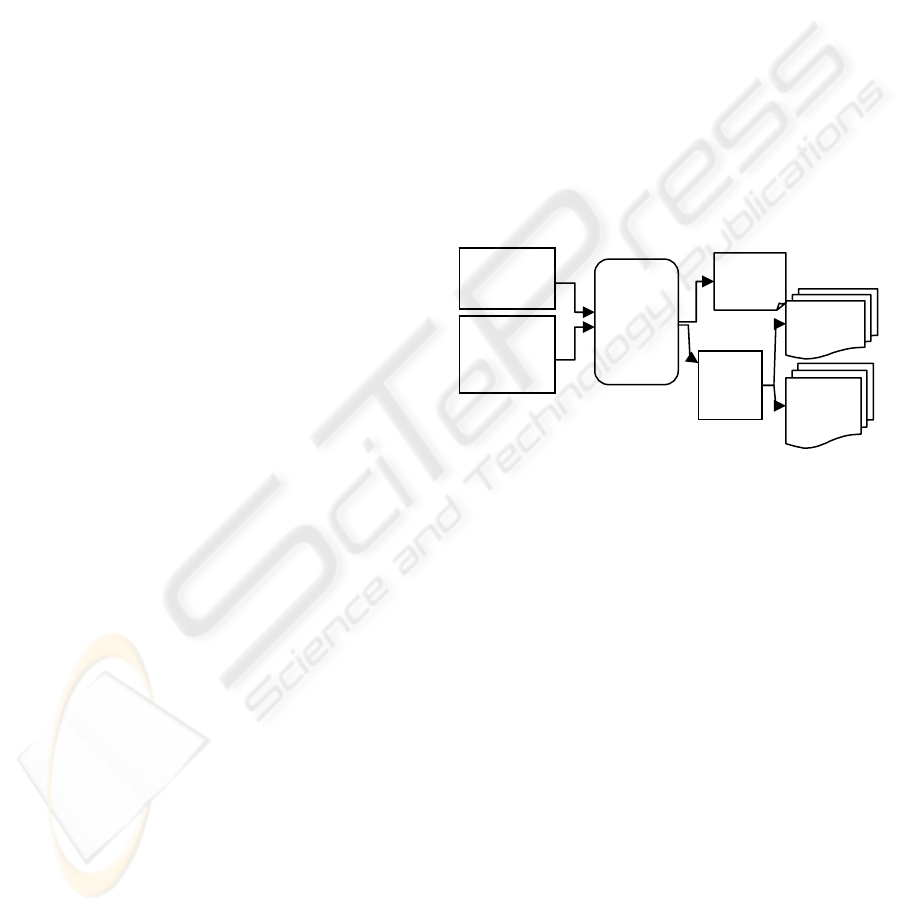

Figure 1 shows the different alternatives

provided by the prototype once the user profile is

created: the information enclosed in it is either

utilized as an input for retrieving documents,

without any further submission of information (we

called it Profiled Answers, PA) or as a tool to

change the order of relevance of the answers

retrieved by the Web4health QA system (Profiled

QA). In the first case, the retrieval algorithm

considers the chosen alternatives as keywords in a

query and retrieves the documents with a matching

combination of categories or diseases. In the second

case it boosts the ranking of the documents that

match topics and objectives chosen or biased by the

user. For the empirical study described in next

section, we presented lists of answers sorted with

and without the user profile in two different

columns, named A and B, so that users and

researchers could more easily compare them.

The matching process is based on a simple

algorithm that works similarly if the user profile is

utilized as a query (Profiled Answers) or as a tool to

boost the ranking of retrieved answers (Profiled

Direct Choice

Indirect

Choice

User

Model

QA

Profiled

QA

Ordinary

QA

Profiled

Answers

Figure 1: Paths of the user model.

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

96

QA). Answers are scored and ranked according to

how well their combination of categories, diseases

and objectives match their counterparts in the user

profile. The retrieved answers are sorted in a

descending order: the closer to the top, the more

relevant the answer is.

The implemented prototype utilizes three-tier

architecture, based on HTTP communication

between a Java middleware and the QA system of

Web4health. The middleware is needed to bridge the

gap between the user and the QA system, which just

processes the submitted queries and returns the

entries from the database according to the template-

matching algorithm (Sneiders, 2002).

4 THE EMPIRICAL STUDY

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the

acceptance of online information and personalized

search services by “lay persons”, i.e. persons

without medical expertise. Within this main

category, two subcategories of end users were

distinguished: 1) Individuals who have “real”

problems and need help to solve their problems 2)

Individuals who are healthy but search for answers

in the areas of psychology and psychotherapy in

order to satisfy their information needs. Two sample

groups representing the afore-mentioned categories

of users were randomly chosen and included in the

study: a group of ten patients, three men and seven

women between 23 and 58 years of age, undergoing

psychotherapy in a private practice, and a group of

ten people, four men and six women between 25 and

59, who saw themselves as healthy and had not been

in contact with psychotherapy before. From now on

we will call them the Therapy Group (TG) and the

Healthy Group (HG).

Since our goal was to evaluate our prototype

from a user perspective, we chose to collect data

through qualitative research methods based on user

observation and in-depth interviews. Nielsen (1993)

advocates the usage of qualitative methods for the

evaluation of information retrieval systems in

particular when it comes to measure user satisfaction

with user interfaces and retrieved information. This

approach was also utilized in studies aiming at

discover how users search medical information the

Web (Eysenbach & Köhler, 2002).

Each user session lasted about one hour and

users were encouraged to think aloud (Long &

Bourg, 1997) while using the system. The interviews

focused on exploring the following issues: (1) which

characteristics are considered crucial by end-users in

a medical portal (2) how the users experienced the

search interfaces (3) how the subjects experienced

the different User Profiling approaches. The retrieval

performance of the system was analysed with a

standard statistical measure for IR: precision (Salton

& McGill, 1983), however the relevance of the

answers retrieved was based on subjective

judgments of the test users. Users were also asked to

rate, on a four-level Lickert scale, how well the

retrieved information managed to satisfy their

information needs.

In order to measure whether adaptivity enhanced

QA we decided to present answers, sorted with and

without considering the UM, in two columns named

A and B. The participants selected the relevant

entries in both columns, without knowing which

column contained which sorting algorithm. This was

done in order not to bias the participants’ judgment

(blind experiment, Chin 2001, p. 182).

5 RESULTS OF THE STUDY

5.1 General Differences

During user observation the researchers noticed that

group therapy patients tried to find answers mainly

related to their own problems and lives, while the

“healthy” group users were mostly interested in

getting general information rather than seeking

advice applicable to their own situation. This

difference was reflected in the search process,

particularly when using the natural language (NL)

panel. In general informants from the HG treated the

system like an electronic version of a medical

encyclopaedia, and the majority of questions

submitted by the HG was quite generic, containing

distinct keywords of the topics the informants

wanted information about, e.g. “What is Bulimia?”.

On the other side it was more noticeable among TG

informants a tendency to write more personal and

vague questions (“How can I feel harmonic?”) or

very specific questions that showed a deeper insight

into a given topic (“Is it possible to overcome a

nocturnal eating disorder?”).

Through the “thinking aloud” method and the

user observation the researchers noticed that most of

the participants tried to satisfy their information

needs according to the following pattern: they first

read the list with the answer headings, containing the

title and a short description of each retrieved answer,

picking the ones that seemed most relevant, then

they followed the link to the bodies of the chosen

answers. One major drawback in this selection

MEDICAL INFORMATION PORTALS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF PERSONALIZED SEARCH MECHANISMS

AND SEARCH INTERFACES

97

process was the fact the participants found it

difficult to see how relevant an answer was, if its

title or short description did not literally contain

the topics they had explicitly asked information

about.

5.2 Search Interfaces

Several users appreciated the possibility to choose

between different navigation paths through the

FAQs: either jumping back and forth between the

list with the answer headings and their bodies, or

following the links to related entries at the bottom of

each answer. This second path was chosen when

highly relevant content was found in one of the

retrieved FAQs: it spurred the subjects to continue

until pages without links came up. Several HG users

criticized the usage of too technical terms defining

the diseases covered by the knowledge base.

Despite the fact that all the participants could

speak and write English fluently, they were not

native speakers, which made the question writing

process more complex. As one user commented:

“even if I do speak and write English well I cannot

master its nuances as I do in my own language. I

would like to be able to write in my own language”.

In some cases users had to reflect “loudly” over how

to spell certain words, which took them extra time to

type sentences.

When the subjects needed generic information

without digging into deep details the Menu-based

interface was considered optimal. The NL-panel

allowed users to be more honest in intimate matters

and to disclose more personal information, which

was of help to work off worries and or give vent to

feelings. This was a common opinion among the

group therapy patients: “I like the fact that you can

submit questions in NL. You can write exactly what

is on your mind” as one user put it. Users, who were

not aware of which topics they needed information

about, appreciated the overview provided by the

menu-based interface: “I like the menus better,

because I can see directly what is available in the

database” as one HG user put it.

Amazingly the NL-based interface was not the

one that received most preferences among TG

participants (see table 1). One reason behind this

result is the fact that several persons from this group

saw it more as a mean to ventilate rather than to

search for answers. Similarly the majority of HG

users liked the menu-based interface better (see table

1); they were more interested in generic information

and appreciated the insight into the knowledge base

given by the form.

Table 1: User preferences about interfaces.

5.3 Profiling Approaches

While observing the users it seemed clear that most

of the participants felt more comfortable providing

their own profile directly. This was also confirmed

in the interview, which unveiled a general

scepticism towards letting the system infer the user

profile. This scepticism was particularly evident

among TG users: a priori they could not understand

how a computer program can infer so important and

sensitive information just monitoring the submitted

questions. They were worried about losing control

and were concerned about being overlooked. HG

users seemed more influenced by technical rather

than emotional aspects, for instance the awareness of

which topics they were interested of: “Well the

explicit approach is better if you know what you are

interested of, but if you are not sure it is better to let

the system infer your profile and choose for you.

Personally I prefer the explicit approach because I

know what I am interested of” as one participant put

it, or simply because they could save time: “The

explicit approach was better, since it took me less

time to create the profile”.

Even if most users preferred submitting personal

information directly, it is interesting to point out that

a large majority of participants (90%) were satisfied

with IC accuracy in inferring their profile.

5.4 Profiled Answers and Profiled

QA

As stated in section 4, the information enclosed in

the user profile was either utilized as an input for

retrieving documents, without any further

submission of information (we called it Profiled

Answers, PA) or as a tool to change the order of

relevance of the answers retrieved by the QA system

(Profiled QA). While observing the users, the

researchers noticed that the informants appreciated

the idea of creating a profile that could be used as a

query for retrieving documents. This positive

impression was also confirmed by the statistical

results of precision (see table 2), as well as by the

user rate of the retrieved answers (see table 3).

Precision was calculated for the documents in the

top five and top ten positions.

Menu-based

interface

NL interface Both

HG 60% 30% 10%

TG 50% 40% 10%

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

98

The precision results and the relevance rates of

HG users are quite similar for both PA and Profiled

QA. This depends on the fact that HG participants

submitted more often generic questions, containing

distinct keywords matching the general topics of the

database, e.g. “eating disorders”, “what is

Bulimia?”. The majority of this category of users

utilized the NL and the menu-based interfaces,

pretty much in the same manner; there were no

substantial differences in the information submitted,

due to the generality of the requests. This led to the

retrieval of rather exhaustive sets of relevant

documents in both cases.

Table 2: Precision results.

Answers Precision-

HG

Precision-TG

Profiled QA top 5 58 % 47%

Profiled QA top 10 52% 41%

Ordinary QA top 5 51% 44%

Ordinary QA top 10 50% 41%

PA top 5 60% 66%

PA top 10 57% 62%

Table 3: How users graded the statement “The retrieved

answers succeeded in satisfying my information needs” in

a four level Lickert scale.

Profiled Answers HG rates TG rates

I totally disagree 0% 0%

I disagree 17% 13%

I agree 66% 54%

I totally agree 17% 33%

QA (Ordinary & Profiled) HG rates TG rates

I totally disagree 0% 0%

I disagree 20% 25%

I agree 65% 60%

I totally agree 15% 15%

The results of the TG participants present more

notable contrasts. Profiled Answers were judged

being about 19% more precise than answers

retrieved by ordinary and profiled QA (see table 2).

TG users also picked the “I totally agree” alternative

for 33% of PA answer sets and 15% of QA answer

sets (see table 3). The main reason behind this

noteworthy diversities lies on the different approach

to the NL-based interface by some TG users. Those

informants tended to see it more as a mean to

ventilate their feelings rather than search for

information and in some cases they tended to write

way too vague questions (e.g. “There is nothing I

can do”) that did not have any matching counterpart

in the manual classification of the FAQ templates.

Thus no matching documents could be found. In

some other extreme cases the sentences enclosed

several keywords that revealed a deeper insight into

medical issues, which leaded to two different

outcomes: in the cases where specific, matching

FAQs were found, the accuracy of the retrieved

answers was extremely high, otherwise no answers

could be provided, due to the physical absence of

any matching FAQs.

5.5 Profiled and Ordinary QA

During the user observation it appeared quite clear

that UM managed to produce better results when it

came to generic questions, i.e. questions that did not

provide a complete picture of the users’ information

needs, or questions that were within the topics

chosen by the user. The ordinary sorting proved to

be better when users submitted questions outside the

range of the topics in the profile, since the retrieval

algorithm of the QA focuses mainly on keyword

matching and do not consider other parameters.

When users submitted questions that were rich of

details, the amount of data provided was sufficient to

retrieve accurate answers and no extra information

was needed. Thus the information contained in the

UM was of no help.

Both HG and TG participants judgments proved

that the quality of the UM-enhanced ranking was

slightly better for the top five answers, with a

difference of 7% for the HG and 3% for TG (see

table 2). The differences tended to fade when it

came to larger sets of answers (e.g. the top ten

answers). The majority of users also explicitly

picked the sorting enhanced by UM as preferable in

the user interview.

5.6 Crucial Characteristics in a

Medical Portal

In order to define which distinctive parameters were

considered as most important in a medical portal, the

respondents were asked to choose from a given list

containing the following attributes: 1) Access portal

information quickly 2) Access portal information

anonymously 3) Find information retrieved from

several sources 4) Find easy, comprehensible

content 5) Find up-to-date information on a weekly

basis 6) Retrieve objective content, i.e. not

influenced by sources with business interests 7) Find

detailed information 8) Submit questions to a human

expert 9) Find information written by reliable and

established sources in medical science.

Users were invited to pick all the parameters that

they considered important and that, in their opinion,

discriminate a good medical portal. Both groups

agreed about the fact that information coming from

MEDICAL INFORMATION PORTALS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF PERSONALIZED SEARCH MECHANISMS

AND SEARCH INTERFACES

99

reliable medical sources was the most important

characteristics. Both groups also valued

comprehensible and up-to-dated content as

important attributes when consulting a medical

portal. The biggest difference between the groups

concerned the possibility of asking a human expert

and the level of detail of the information provided.

Seven users from HG estimated detailed information

as salient, while only three users from TG

considered it an important factor. Furthermore only

three HG users were interested in asking a human

expert, unlike TG, where eight persons considered it

crucial. This difference can be explained considering

that the two groups searched for information with

two different purposes: the group-therapy patients

posed questions mainly related to their own

problems, seeking advice applicable to their own

situation, while the “healthy” group users were

mostly interested in getting information covering

medical areas from a popular, scientific point of

view, i.e. they consulted it as an encyclopaedia or a

medical book. Another remarkable difference

between the groups concerns the anonymity factor:

seven participants from TG agreed about its great

usefulness but only four from HG shared the same

opinion.

6 DISCUSSION

The results of this study provide indications about

the parameters that users with different needs

consider relevant on medical portals, the role of UM

in the retrieval of medical information and how

users experience UM and different search interfaces

on medical portals.

6.1 Crucial Characteristics in a

Portal

Users in general, regardless of their background,

value information coming from several reliable

medical sources, up-to-dated and comprehensible

content. People with medical problems are more

concerned about reading information not influenced

by parts with business interests and appreciate the

possibility to submit questions to human experts.

They also appreciate to access portal information

anonymously. People without open medical

problems are more interested in detailed information

than asking questions to human experts or accessing

information anonymously. These results confirm

what Eysenbach and Köhler (2002) discovered in

their studies in matters of criteria for trustworthiness

of medical sites. The authors found out that users

prioritized readability, professional layout, and

updated content coming from authorities in the field.

6.2 The Role of UM in the Retrieval

of Medical Information

The results of our study have indicated that in

general UM can enhance the information seeking

process and the precision of the retrieved

documents. This works both for individuals who

need help with their problems and individuals, who

are healthy, but search for answers in order to satisfy

generic information needs. The results were more

evident for the answers listed in the top five

positions. Generic requests or requests that were not

rich of details benefited the most from the UM, since

the information contained in the user profile added

more specificity, or completed what was stated in

the NL sentences. This helped the system to

prioritize better among the retrieved answers,

improving its ranking mechanism. Unfortunately our

prototype did not implement any functionality to

automatically re-edit fuzzy NL sentences before

submitting them. When users (mostly patients)

submitted questions that were too vague, no

matching answers could be found, since the retrieval

algorithm of the QA system focused on keyword

matching. In order to avoid this problem, the

information contained in the UM should be used to

fill this gap, re-editing or complementing indefinite

sentences before submitting them. This solution

would also reduce the cognitive workload of the

users. This is quite important, considering the fact

that people suffering from medical problems,

because of their condition, are already subjected to

mental stress and they are not supposed to remember

all the details of their information need in order to

receive precise answers.

Another drawback that our study has revealed is

what we defined as the “lock-out” problem: users

that asked questions outside of the topics specified

in the profile did not receive any benefit at all in the

sorting process, since no retrieved entry could be

prioritized. This outcome evidences the need to

implement a more dynamic profiling mechanism

that takes into consideration user questions even

after his/her profile has been created. Another case,

where the information contained in the UM proved

to be unhelpful, was when very specific questions or

questions that were rich of details were submitted:

the amount of data provided was sufficient to

retrieve accurate answers and no extra information

was needed.

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

100

Our user interview has shown that users with

different characteristics are interested in different

levels of details in the information provided: only

30% of users suffering from mental problems found

detailed information relevant, unlike “healthy” users,

where a clear majority, 70%, found it necessary.

This confirms that it is important to adapt the style

and the content of retrieved documents to users’

background and search goals.

6.3 Direct or Indirect UM?

Our study has revealed that people in general

users are sceptical towards letting computer

programs monitor their steps and indirectly infer

their profile. The reasons behind this scepticism

were mostly emotional and technical. The emotional

reasons reckoned with the fear of losing control and

being overlooked (mostly TG users). The technical

reasons regarded parameters such as savings of time

or avoidance of misunderstandings (mainly HG

users).

For what concerns the individual information

needs, people who know what they are interested of,

or what their problem is, usually tend to prefer the

explicit approach, since they can specifically choose

the topic or the disease they need information about.

On the other side, people who do not know in the

first place which kind of information they

necessitate, tend to prefer the implicit approach,

since it draws conclusions from their interaction

with the system and proposes topics that can be

relevant to their information needs.

In general we can conclude that the direct

profiling is the choice that is best accepted by users.

The creation of the profile is not subjected to risks of

wrong assumptions or misunderstandings that may

occur in the monitoring process. Those risks are

particularly evident in cases where the profile is

created tracking the NL input of the user. NL

sentences can be very ambiguous and can have

different meanings in different contexts. Those

difficulties become even more evident when NL-

input in a foreign language is required.

Monitoring human-computer interaction on other

interface parts, e.g. mouse clicks on chosen links, in

order to find indicators of the user interests, is not

fully trustworthy either. Users may misunderstand

the available choices; links may be selected just for

curiosity or to confirm the user knowledge in a

certain topic (Kobsa, Koenemann & Pohl, 2001).

Considering the sensitiveness of the information

provided on medical portals, we want to avoid any

possible misunderstanding that can arise from wrong

assumptions; so direct profiling is preferable.

6.4 NL or Menu-Based Interface?

The affordance (Norman, 1999) of the menu-based

interface enables users to produce relatively short,

generic queries and does not provide much

flexibility in the search process, since the language

nuances cannot be exploited. This fits more the

search of users who utilize the information portal as

an electronic medical book and have rather generic

information needs (mainly users without health

problems). This technique fits also topics where

users tend to submit requests that can be

summarized to few standard queries; for instance

cancer (Bader & Theofanos, 2003).

Users who have troubles in formulating their

own information needs in NL sentences can also

benefit from the menu-based interface, since they

can choose from a list of pre-selected topics. Thus

the menu-based interface reduces the cognitive

workload and does not force users to come up with

questions matching their information needs.

On the other hand the NL-based interface is more

suitable: 1) In counselling or dialoguing matters, in

other words when users want to open up and submit

a problem for examination or discussion, or simply

just want to ventilate their feelings. The NL-

interface can better resemble the doctor/patient

verbal interaction and give users more control over

the input to be submitted 2) When users have an

explicit, specific and detailed question in their mind

or want to exploit the nuances of the human

language.

The level of expertise in the knowledge domain

can also determine the adequacy of the search

interface. Our study showed that users that were not

familiar with medical terms could not take full

advantage of the form-based search. Through NL-

based interfaces users can freely express themselves

in own words that correspond to their own

individual level of expertise in the domain. It is

though important to support multilingual input, so

that users can submit questions in their own

language.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study provide the following

indications to help developers in the implementation

of medical portals on the Web:

- Implement UM on medical portals: this

research has shown that UM can enhance the

information seeking process and the quality of the

retrieved information on medical portals. UM is also

MEDICAL INFORMATION PORTALS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF PERSONALIZED SEARCH MECHANISMS

AND SEARCH INTERFACES

101

useful when we do not want to burden the cognitive

workload of the users in the process of formulating

their information needs. Thus the “one-size fits all”

information delivery approach available on medical

portals should be changed.

The user model should evolve dynamically in

order to avoid what we have defined as the “lock-

out” problem. Since users seem sceptical towards

letting computer systems infer their profile, it is

preferable to let users create their own profile

explicitly.

- Implement different search interfaces: our

research has shown that menu-based and NL-based

interfaces fit different types of information needs

and allow different levels of specificity. Users

should be able to choose between both types of

interface.

- Adapt the description of retrieved documents:

as stated in section 5.1, users may sort out relevant

documents only because the headings do not

explicitly name the topics they ask information

about. Thus it is important to generate descriptions

in real time that explicitly link the content of the

documents to users’ information needs.

- Allow users to submit questions in their own

language: formulating information needs in NL is

not an easy task, especially when it comes to foreign

languages. In order to reduce misunderstandings and

fully exploit the nuances of NL, it is preferable to

implement search interfaces that support

multilingual input, so that users can submit

questions in their own language.

- Implement the “ask human experts”

functionality and allow anonymous information

access: our interview has revealed some differences

concerning what the two user groups prioritize on a

medical portal. Two of the biggest differences

concerned the possibility to submit questions to

human experts and to access portal information

anonymously. If the portal is aimed at helping

people with medical problems, then these

functionalities should be available.

REFERENCES

Bader, J.L., & Theofanos, M.F., 2003. Searching for

Cancer Information on the Internet: Analyzing Natural

Language Queries. Journal of Medical Internet

Research, 5, Article e31. Retrieved September 2005

from http://www.jmir.org/2003/4/e31.

Bental, D., et al., 2000. Adapting Web-based information

to the needs of patients with cancer. In AH’00, 1st

International Conference on Adaptive Hypermedia.

Springer-Verlag.

Boyle, C., & Encarnacion, A., 1994. Metadoc: an adaptive

hypertext reading system. User Modeling and User-

Adapted Interaction, 4, 1-19.

Brajnik, G., Mizzarro, S., & Tasso, C., 1996. Evaluating

user interfaces to IR systems. In SIGIR’96, 19

th

Conference on Research and Development in

Information Retrieval. ACM press.

Chin, N., 2001. Empirical evaluation of User Models and

User-Adapted Systems. User Modeling and User-

Adapted Interaction, 11, 181-194.

Eysenbach, G., Sa, E.R., & Diepgen, T.L., 1999. Shopping

around the Internet today and tomorrow towards the

millenium of cybermedicine [Electronic Version].

BMJ, 319, 1-5.

Eysenbach, G., & Köhler, C., 2002. How do consumers

search for an appraise health information on WWW?

Qualitative study using focus groups, usability tests

and in-depth interviews [Electronic Version]. BMJ,

324, 573-577.

Grasso, F., Cawsey, A., & Jones, R., 2000. Dialectical

argumentation to solve conflicts in advice giving: a

case study in the promotion of healthy nutrition

[Electronic Version]. Int. J. of Human Computer

Studies, 53, 1077-1115.

Kass, R., & Finin, T., 1998. Modeling the user in natural

language. Computational Linguistics, 14, 5-22.

Kobsa, A., Koenemann, J., & Pohl, W., 2001.

Personalized hypermedia presentations techniques for

improving online customer relationships [Electronic

Version]. The Knowledge Engineering Review, 16,

111-155.

Lennox A., et al., 2001. Cost effectiveness of computer

tailored and non-tailored smoking cessation letters in

general practice: randomised trial [Electronic

Version]. BMJ, 322, 1-7.

Long, D., & Bourg, T., 1996. Thinking aloud: telling a

story about a story. Discourse Processes, 21, 329-339.

Lyons, C., Krasnowski, J., Greenstein, A., Maloney, D., &

Tatarczuk, J., 1982. Interactive Computerized Patient

Education. Heart and Lung, 11, 340-341.

Micarelli, A., & Sciarrone, F., 2004. Anatomy and

Empirical evaluation of an adaptive Web-based IF

system. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction,

14, 159-200.

Moon, J., & Burstein, F., 2005. Intelligent Portals for

supporting Medical Information needs. In Web

portals: the New Gateways to Internet Information

and Services, pp. 270-289. Idea Publishers.

Nielsen, J., 1993. Usability Engineering. Academic Press.

Norman, D.A., 1999. Affordances, Conventions and

Design. Issue of Interactions, 6, 38-43.

Salton, G., & McGill, M., 1983. Introduction to modern

Information Retrieval. McGraw-Hill.

Santos, E., Nguyen, H., Zhao, Q., & Pukinskis, E., 2003.

Empirical evaluation of adaptive UM in a medical IR

application. In UM’03, 9

th

Int. Conference on User

Modeling. Springer-Verlag.

Sneiders, E., 2002. Automated Question Answering:

Template-Based Approach. PhD thesis, Royal Institute

of Technology, Sweden.

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

102