Countering the Cybercrimes: Problems of Criminal Law and

Criminal Intelligence Operations at the International Level

Kirill Konstantinovich Klevtsov

1

and Aleksandr Valerievich Kvyk

2

1

Department of Criminal Law, Criminal Proceedings and Criminalistics, PhD in Law,

Moscow State Institute of International Relations (University) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation,

Moscow, Russian Federation

2

Department of Criminal and Legal Disciplines, Open Institute of Law, Vladivostok, Russian Federation

Keywords: Cybercrime, operation of criminal law in space, cooperation in criminal intelligence operations, information

retrieval from communication channels, computer information receipt.

Abstract: The article highlights particular problems of operation of criminal law in space concerning cases on the crimes

in the sphere of computer information, as well as touches on modern difficulties of criminal intelligence

operations in this sphere. Particular attention is paid to some issues of interaction of the Russian criminal

intelligence authorities with the competent foreign authorities or the service providers from abroad. The

purpose of this article is to identify various interpretations in the definition of the criminal jurisdiction in order

to develop a unified approach to the definition of the operation of criminal law in space, as well as the

determination of the modern problems of the international cooperation in the sphere criminal intelligence

operations on the commitment of cybercrimes irrespective of the place of their commitment. The work has

proven that the most of the authorities engaged in criminal intelligence operations practice the receipt of

electronic information being of interest and physically located in the territory of the other sovereign,

independently, without prior consent of the relevant state. Generally, this is realized in two ways: 1) by remote

real time connection to the subscriber device of the person of interest by means of such criminal intelligence

operations as information retrieval from communication channels or computer information receipt; 2) by

actual seizure of the electronic data storage device from a victim or an eyewitness with its further investigation

to find out the intelligence information.

1 INTRODUCTION

The articles sought to consider the issues of the

operation of criminal law in space in cybercrime

cases. The following principles of the criminal

jurisdiction are analyzed: 1) territorial; 2) nationality

(active and passive); 3) real (safety); 4) universal.

In the given research, the definition of

cybercrimes goes beyond the socially dangerous

actions provided by Chapter 28 “Crimes in the sphere

of computer information” of the Criminal Code of the

Russian Federation (hereinafter - the CC of the RF).

We think that the definition should include, in

addition to the actions aimed against confidentiality,

integrity and accessibility of computer data or

systems, as well as the actions supposing the use of

computer means for the purposes of personal or

financial benefit, or personal or financial damage,

including the kinds of the criminal activity related to

the personal data use.

The legal analysis of the national legislation and

the practice of different states in the sphere of

criminal intelligence operations evidences the

absence of a unified approach to combating

cybercrimes (Bellers H., 2016). This has a negative

impact on the performance of the states in the area

under consideration. Many legislative and law-

enforcement problems different states face in the

course of combating cybercrimes were summarized

in the Report of the UN Secretary-General at the

seventy-fourth session of the United Nations General

Assembly entitled “Countering the use of information

and communications technologies for criminal

purposes” (UN Secretary-General, 2021).

We have also analyzed the forms of the criminal

intelligence interaction in the framework of

documenting the specified crimes, determined and

studied some problems of such cooperation, as well

as offered possible options of their solution. It is

offered to use only the traditional legislative tools and

Klevtsov, K. and Kvyk, A.

Countering the Cybercrimes: Problems of Criminal Law and Criminal Intelligence Operations at the International Level.

DOI: 10.5220/0010632400003152

In Proceedings of the VII International Scientific-Practical Conference “Criminal Law and Operative Search Activities: Problems of Legislation, Science and Practice” (CLOSA 2021), pages

133-139

ISBN: 978-989-758-532-6; ISSN: 2184-9854

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

133

methods as the prospective cooperation of the

criminal intelligence authorities in combating

cybercrimes. In addition, there is the author’s concept

on consolidation in the international treaties and

national legislation of the provisions ensuring the

direct data access of the law enforcement authorities

by applying actually to the service providers located

abroad.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

The theoretical basis for this article were the works of

the representatives of the science of substantive and

procedural law, as well as criminal intelligence

operations on the topic of the research. The

theoretical basis were the current Russian criminal

legislation and criminal intelligence legislation,

regulatory acts of the foreign countries, as well as

international treaties in the sphere. The empirical

basis for the article were the analyzed 28 inquiries of

the criminal intelligence units of the Ministry of

Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation, including

18 inquiries of the Interpol National Head Bureau, as

well as the results of interview of 46 criminal

intelligence servants of different units of the Ministry

of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation and the

Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation.

The materialist dialectic, legal hermeneutics,

special juridical, comparative law, sociological and

forecasting methods were used in the course of legal

analysis.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Operation of Criminal Law in

Space Regarding Cybercrimes

From a traditional point of view, the operation of

criminal law in space supposes criminal jurisdiction

and is related to the territorial principle that is clearly

illustrated in Article 11 of the CC of the RF. At this,

the summary of materials of the criminal cases on

cybercrimes evidences that not always the law

enforcement authorities of foreign states restrain from

intervention in the interior affairs of the Russian

Federation. The mentioned prescription must be also

observed when the citizens of one state are the figures

of the criminal case and stay in the territory of another

state as the enforcement criminal jurisdiction of the

states is of restrictive nature (Farbiarz, 2016).

In this regard, the Report of the Council of the

European Committee on Crime Problems on

Extraterritorial Criminal Jurisdiction

1

states that a

sovereign shall not be entitled to exercise its

jurisdiction in the territory of another sovereign

without its consent.

It is obvious that not every crime takes place

within one territorial unit. That is why it is no wonder

that the formed culture of responsibility for

international crimes gives rise to the further exercise

of criminal jurisdiction on the basis of extraterritorial

principles (Grant, 2018; Curley and Stanley, 2016).

The fundamental principles of the criminal

jurisdiction are reflected in the domestic law of each

of the states where all principles are based on the idea

of “necessary connection” that consists in the

connection between the committed act and the

country having the right to exercise its jurisdiction

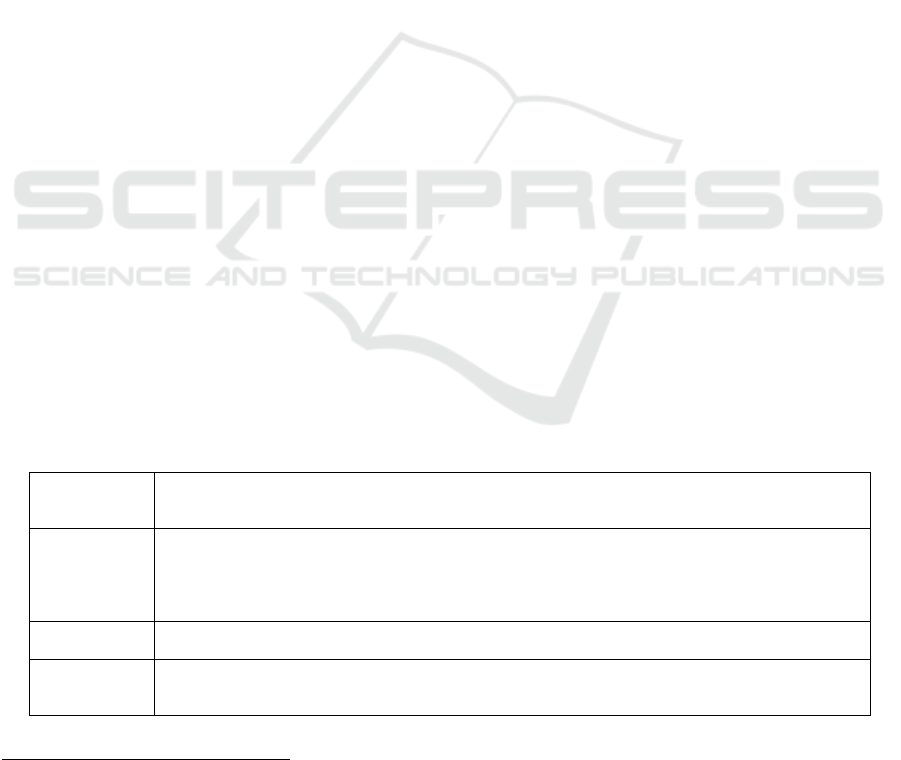

Table 1: Principles of operation of criminal law in space according to the CC of the RF and of the foreign states

Territorial

principle

The state is entitled, within its territory, to exercise the function of criminal prosecution of persons irrespective

of their nationality who committed the crime in the territory of this state or any of the elements of such crime,

including the consequences covering this state.

Nationality

principles

(active)

(passive)

The criminal jurisdiction depends on the nationality of a person

Irrespective of the fact where the crime is committed, the jurisdiction is determined on the basis of the

nationality of the suspect (accused person)

Irrespective of the place of commitment of the socially dangerous act, the criminal jurisdiction is determined

on the basis of the nationality of the victim.

Real principle The exercise of jurisdiction takes place of the crime that was committed outside the state but caused damage

to the interest it protects (for example, security, etc.).

Universal

principle

The jurisdiction can be applied irrespective of the place of crime provided that such socially dangerous act

belongs to the “international crimes” (piracy, military crimes), and the state, in which territory the supposed

offender stays, cannot or does not wish to bring him to the criminal responsibility.

1

Report of the Council of the European Committee on

Crime Problems on Extraterritorial criminal jurisdiction.

Strasbourg, 1990. - p. 7, 17–18.

CLOSA 2021 - VII INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC-PRACTICAL CONFERENCE “CRIMINAL LAW AND OPERATIVE SEARCH

ACTIVITIES: PROBLEMS OF LEGISLATION, SCIENCE AND PRACTICE”

134

with regard to such socially dangerous act (Ambos,

2018). In respect to the Russian Federation, these

principles are reflected in Art.Art. 11-12 of the CC of

the RF.

3.1.1 Territorial Principle of Criminal Law

with Regard to Cybercrimes

The criminal legislation of the Russian Federation

and most of the foreign states, as well as all

international treaties on combating cybercrimes

provide for territorial principle of exercise of the

criminal jurisdiction (Maillart J., 2019). For example,

Art. 22 of the Convention on Cybercrime (Budapest,

November 23, 2001) (hereinafter - the Convention on

Cybercrime of the Council of Europe), Art. 30 of the

Arab Convention on Combating Technology

Offences dated December 21, 2010, Art. 4 of the

Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of

the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution

and Child Pornography (New York, May 25, 2000),

etc. At this, the criminal legislation and the

international treaties in this sphere do not oblige to

take into account that all elements of crime are

exercised in the territory of the same sovereign for the

territorial principle implementation. Therefore, the

Explanatory Report to the Convention on Cybercrime

of the Council of Europe states that the territorial

principle can be also applied in the situations when a

victim and an offender stay in the territories of

different states (Council of Europe, 2001).

In this connection, the legal doctrinal analysis and

summary of the foreign investigative judicial practice

show that the law-enforcement authorities use the

territorial jurisdiction if (a) all elements of the crime

were implemented in the territory of their state,

excluding the consequences or (b) the consequences

of the crime (for example, the caused property

damage as a result of fraud) exist within their state,

and the act and location of the prosecuted persons -

outside of their territory (United States District

Court).

3.1.2 Operation of Criminal Law According

to the Nationality Principle Regarding

Cybercrimes

In addition to the territorial principle, the

international treaties designed for combating

cybercrimes provide for criminal jurisdiction on the

basis of active nationality. The legal essence of this

notion consists in that the state should ensure

jurisdiction when the crime is committed by its

citizen, even in cases if such a social act is committed

outside the territory of the country (Ferzan K., 2020).

At this, some regulatory documents require that such

an act is also recognized as a crime in the state where

it was committed.

It should be emphasized that a number of

countries, which national legislation provides the

nationality principle, use such criminal jurisdiction on

the crime irrespective of the place of their

commitment provided that they were committed by

their citizens (Megret2020).

3.1.3 Application of Other Principles of

Operation of Criminal Law in Space

Regarding Cybercrimes

Analysis of the Russian criminal law (Art. 12) makes

possible to conclude that the CC of the RF also

provides the real and universal principles of law. The

domestic law of the other countries also mostly

contains the provisions on implementation of the real

principle of the jurisdiction (defense of state interests)

if certain conditions are present, of course. For

example, the USA have the right to apply own laws

regarding socially dangerous acts committed abroad

if these acts threaten its national security (decision of

the United States Court of Appeals (on the I Court of

Appeals for the Federal Circuit) on the case United

States v. Cardales, 168 F. 3d 548 (1st Cir. 1999)). The

situation with a determination of the universal

jurisdiction is different as it is implemented by most

of the states when a person committed the

“international crime” stays in their territories.

However, traditionally, cybercrimes are not included

in the list of the above crimes.

3.1.4 Clash of Criminal Jurisdictions

Various national regulations of jurisdictional grounds

can create the situations when every state will have an

opportunity formally to spread the action of its

criminal law on any cybercrime irrespective of the

place of commitment and other important

circumstances (Zając D., 2020) that will lead, as it is

supposed, to chaotic and unreasonable “dispersion”

of the criminal jurisdiction. By the way, most of the

international treaties determine a generic framing for

the problem the states can face in case of the

appearance of the “parallel” jurisdiction (Kaumova,

2018).

For example, Art. 22 of the Convention on

Cybercrime governs the situations when the crime

falls within the criminal jurisdiction of two or more

countries, as a result any of them can exercise the

prosecution on the basis of the data available. At this,

such state must interact with the other sovereign

damaged by this crime for the purposes of

Countering the Cybercrimes: Problems of Criminal Law and Criminal Intelligence Operations at the International Level

135

information exchange to determine optimal legal

prospects of the case.

However, many states have no national regulation

for conflicts of the criminal jurisdictions. This is most

likely determined by that it is rather difficult to

forecast a certain vector of development for all cases

regarding transnational crimes. That is why it is

supposed that the disputes in the sphere of the

criminal jurisdiction should be settled through formal

and informal consultations with the other states,

particularly, through the channels of such

international organizations as Interpol, Europol and

Eurojust (Volevodz A.G., 2019; Ring T., 2021) to

prevent “parallel” proceedings.

3.2 Modern Practice of Receipt of

Electronic Information in the

Framework of Criminal

Intelligence Operations on

Cybercrimes

3.2.1 Actual Seizure of the Electronic Data

Storage Device

As a rule, the law enforcement authorities receive the

intelligence information on cybercrimes in the course

of direct and public seizure of data storage devices

(smartphones, tablets) (Klevtsov K.K., Kvyk A.V.,

2020). Also, such seizure can be carried out in the

framework of criminal intelligence operations (P. 1,

Art. 15 of Law No. 144-FZ “On Criminal Intelligence

Operations” (hereinafter - the EIO Law) dated

12/08/1995. The EIO Law requires from an official

withdrawing the data storage device to have a

resolution on criminal intelligence events (hereinafter

- the EIE) and draw up a protocol.

The officials of the criminal intelligence units

often withdraw the electronic devices during actual

arrest, in the course of which the detainee’s pat search

is performed. At the same time, the information

contained on the electronic data storage device can be

received during its direct seizure in the framework of

the examination of the premises. In future, the data

are investigated in the framework of the EIE “the

receipt of computer information” (cl.cl. 15, Art. 6 of

the EIO Law).

3.2.2 Remote Interception of Electronic

Information

The most common “remote interception” on the

cybercrime cases is the EIE in the form of electronic

surveillance. In its course, the criminal intelligence

servants by covert means install the audio/video

recording devices in a vehicle, room or dwelling to

supervise the monitored object.

The operational entities also can contact a person

who holds correspondence, for example, by means of

messenger, with a verified person. This provides for

monitoring the correspondence by means of

voluntary and direct provision of the electronic data

storage device by one of the parties of the

correspondence. In such cases, the law does not

protect a secret of private negotiations as one of the

parties discloses it (Constitutional Court of the

Russian Federation, 1997; Constitutional Court of the

Russian Federation, 2006).

Besides, the law enforcement authorities can

contact with the monitored object through the persons

assisting them and having access to the mobile device

of the person of interest. At this, the corresponding

program can be used to connect to the device of the

person of interest, after that all its data are reproduced

to the device of the monitoring subject in inversed

manner.

It is technically feasible to use it for remote access

to the electronic information of the SIM-card

duplicate the relevant messenger is linked to. Finally,

the spyware sent by mailout to the person of interest

for interception of correspondence or the special

technical means for interception of electronic

information real time are used.

The above methods of interception of

correspondence in messengers are implemented

within the EIE, retrieval of information from

communication means that require the order of the

head or the deputy head of the corresponding law

enforcement unit.

3.2.3 Receipt of Information Upon Request

in the Framework of Criminal

Intelligence Operations

Not in each case, the criminal intelligence servants

can seize a device or intercept a message from e-mail

or messenger on the cybercrime cases. Such situation

occurs when the service provider is located in the

territory of the foreign state, as a result, the operation

of the Russian criminal intelligence law is limited by

the territorial principle. In this case, the most efficient

tool for getting the correspondence provided

electronically is to send an inquiry for assistance to

the competent bodies of the host country of the search

object and/or to the service provider.

The interaction of the Russian criminal

intelligence authorities with colleagues from foreign

states is implemented in the framework of the

intergovernmental and inter-agency agreements. The

CLOSA 2021 - VII INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC-PRACTICAL CONFERENCE “CRIMINAL LAW AND OPERATIVE SEARCH

ACTIVITIES: PROBLEMS OF LEGISLATION, SCIENCE AND PRACTICE”

136

summary of 28 inquiries for assistance sent by the

criminal intelligence units of the MIA of Russia and

their further legal analysis demonstrated that such

documents are sent only in the framework of the

intergovernmental and inter-agency agreements

(primarily). Also, the Interpol NCB channels are used

on the basis of the documents of this international

organization. The EIO Law does not give a

comprehensive view concerning international treaties

that constitute the legal basis and concerning

international cooperation. The exclusion is P. 6 of

Art. 7 stating that the basis for criminal intelligence

events are the inquiries of the international

governmental organizations and law enforcement

authorities of the foreign states according to the

international treaties. That is why the legal basis for

interstate cooperation in the sphere of criminal

intelligence operations are P. 4, Art. 15 of the

Constitution of the Russian Federation and P. 1 and

P. 3, Art. 5 of the Federal Law “On International

Treaties of the Russian Federation” (Shumilov A.Yu.,

2008).

The lacking direct legal regulation of this issue is

a problem for executors of law. Thus, according to

our social research results (46 servants of various

criminal intelligence units of the Ministry of Internal

Affairs of the Russian Federation and the Federal

Security Service of the Russian Federation were

interviewed), the following has been obtained. 41

respondents indicated the practical necessity to

include the norm in the EIO Law that provides for

using the international treaties (intergovernmental

and inter-agency) or the principle of reciprocity,

similarly to Art. 453 of the CPC of the RF, as the basis

for cooperation. The other 5 respondents noted that

the inclusion of such norm is impractical.

The criminal intelligence units often apply

directly to the service provider by the official e-mail

requesting to ensure data integrity or use the Interpol

NCB channels (Volevodz A.G., 2016; Klevtsov K.K.,

2018). It is necessary to take into account the specific

nature of the rules developed by the service provider.

As a rule, the instant messaging service provider has

a special portal on its official website determining the

basis, conditions and procedure of interaction with

law enforcement authorities, and the criminal

intelligence interaction in the framework of the

intergovernmental and inter-agency agreements

makes it possible to solve common technical and

legal problems through consultations between law

enforcement authorities for the purposes of further

optimization of official actions (Litvishko P.A.,

2015).

At the same time, the opportunity to get the

requested information through the full-time

specialized contact centers, as a rule, within several

days evidences the efficiency of international

cooperation of the police. Bases on the summarized

law enforcement practice, the criminal intelligence

cooperation is used for proving the identification or

subscriber information, as well as for operations

support of the electronic data integrity and traffic

(Malov A., 2018; Litvishko P.A., 2017).

At the same time, it can be difficult and sometimes

almost impossible in the criminal intelligence

practice immediately to identify where the electronic

data on cybercrimes are physically located (Li X., Qin

Y., 2018), as they can be in several places (states)

being the data or data copy processing centers at a

time (Peterson Z.N.J., Gondree M., Beverly R.,

2011), and the contractual relations between such

service providers and their users not always

determine the location of the data processing centers

(Benson K., Dowsley R., Shacham H., 2011).

Correspondingly, such data are fully controlled by

the state that legally holds them but not by the state

where the data processing center is physically located

(Sieber U., 2012).

In connection with the adoption of the CLOUD

Act - Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act”

in the USA in 2018, the US criminal intelligence

authorities can have access to the electronic data,

especially on cybercrimes, the American companies

store on foreign servers provided that they have direct

access to such data (Schomburg W., Lagodny O.,

2020). In other words, the police or the Federal

Bureau of Investigation can oblige Google or

Facebook to provide the user data if they are

physically stored, for example, in Europe (Berengaut

A., Lensdorf L., 2019).

In addition, there are various criminalistic wiles to

make the Internet providers give the information

being of interest for law enforcement authorities

(Goldfoot J., 2011).

4 CONCLUSIONS

Considering the above, it can be concluded that the

cybercrimes are transnational if any element of crime

or consequence takes place in the territory of the other

country. This, of course, touches upon the issues of

state sovereignty and international interaction.

The international and domestic law of a number

of sovereigns set forth, primarily, the similar

principles of operation of the national criminal law on

Countering the Cybercrimes: Problems of Criminal Law and Criminal Intelligence Operations at the International Level

137

cybercrimes (real, universal, territorial, nationality

(active and passive) principles.

In connection with the appearance of cloud

technology and unstable nature of electronic

information, it appeared to be difficult to get them in

practice. Today, the criminal intelligence units use the

alternative methods to get the required electronic

information in combating cybercrimes (1) real time

connection to the device using special technical

means, (2) seizure of other device that may store such

information and its further inspection without consent

of the other state in which territory such data are

physically located. In rare cases, as practice shows,

the law enforcement servants can get the electronic

data directly from the service providers located

abroad in the framework of the sent inquiry for

assistance.

One of the ways for optimization of the

international cooperation in the sphere of criminal

intelligence operations on cybercrimes would seem to

supplement paragraph one, Article 4 of the EIO Law,

with the following sentence:

“The common principles and norms of the

international law and the international treaties of the

Russian Federation also can constitute the legal basis

for the criminal intelligence operations. It is not

allowed to apply the rules of the international treaties

of the Russian Federation in their interpretation

contradicting the Constitution of the Russian

Federation. Such contradiction can be established in

a manner determined by the federal constitutional

law”.

We suppose that the offered version of the article

of the Russian criminal intelligence is the subject of

the scholarly discussion. However, its introduction is

generally necessary for the purposes of creation of the

legal basis for efficient activities described.

REFERENCES

UN Secretary-General, 2021. Report at the seventy-fourth

session of the United Nations General Assembly

entitled “Countering the use of information and

communications technologies for criminal purposes”.

https://www.unodc.org.

Council of Europe, 2001. Explanatory Report to

Convention on Cybercrime. https://rm.coe.int.

United States District Court. In US v. Tsastsin et al.

Southern District of New York. 2(11). p. 878.

Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation, 1997.

Rulings №72-О.

Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation, 2006.

Rulings № 454-О.

Volevodz, A.G., 2019. Mutual legal assistance in criminal

cases: cooperation with the states of offshore

jurisdictions of the Romano-Germanic legal family

(continental law systems). In Russian Investigator. 10.

pp. 64-68.

Volevodz, A.G., 2016. Some aspects of investigation

planning in the international cooperation in the sphere

of criminal procedure. In Criminal Procedure. 3. pp.

26-33.

Klevtsov, K.K., 2018. Pre-trial procedure regarding the

persons evading criminal responsibility outside the

territory of the Russian Federation. In Yurlitinform. p.

15.

Klevtsov, K.K., Kvyk, A.V., 2020. Seizure and review of

information stored in the electronic memory of

subscriber devices. In Zakonnost. 12. pp. 59-60.

Litvishko P.A., 2017. International legal forms of search of

persons abroad. Criminalist’s Library. In Scientific

Journal. 2. pp. 106-116.

Litvishko, P.A., 2015. Integration of pre-trial investigation

and criminal intelligence operations: foreign and

international experience. Criminalist’s Library. In

Scientific Journal. 3. pp. 309-319.

Malov, A., 2018. Reception of electronic evidence from

foreign jurisdictions (in the example of the USA). In

Zakonnost. 9. pp. 56-60.

Shumilov, A.Yu., 2008. Criminal intelligence operations:

questions and answers. In Book I: General provisions.

3. PUBLISHING HOUSE OF SHUMILOVA I.I. p. 40.

Ambos, K., 2018. International Economic Criminal Law. In

Crim Law Forum. 29. pp. 499–566.

Benson, K., Dowsley, R., Shacham, H., 2011. Do you know

where cloud files are? In: Proceedings of the 3rd ACM

Workshop on Cloud Computing Security. CCSW. 11.

pp. 73-82.

Bellers, H., 2016. Cybercrime. In HEADline. 33. pp. 24-25.

Berengaut, A., Lensdorf, L., 2019. The CLOUD Act at

Home and Abroad. In Computer Law Review

International. 20. pp. 111-117.

Curley, M., Stanley, E., 2016. Extraterritorial Jurisdiction,

Criminal Law and Transnational Crime: Insights from

the Application of Australia's Child Sex Tourism

Offences. In Bond Law Review. 28. pp. 169-197.

Farbiarz, M., 2016. Extraterritorial criminal jurisdiction. In

Michigan Law Review. 114. pp. 507-558.

Ferzan, K.K., 2020. The Reach of the Realm. Criminal

Law, Philosophy. 14. pp. 335–345.

Grant, C., 2018. The Extraterritorial Reach of Tribal Court

Criminal Jurisdiction. In SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.

pp. 2139.

Kaumova, A., 2018. Conflicts of Criminal Jurisdiction of

States and Extradition Issues. In Helix. 8. pp. 4638-

4644.

Li, X., Qin, Y., 2018. Research on Criminal Jurisdiction of

Computer cybercrime. In Procedia Computer Science.

131. pp. 793-799.

Goldfoot, J., 2011. Compelling Online Providers to

Produce Evidence Under ECPA. In The United States

Attorneys Bulletin (Obtaining and Admitting Electronic

Evidence). 59(6). pp. 35-41.

CLOSA 2021 - VII INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC-PRACTICAL CONFERENCE “CRIMINAL LAW AND OPERATIVE SEARCH

ACTIVITIES: PROBLEMS OF LEGISLATION, SCIENCE AND PRACTICE”

138

Maillart, JB., 2019 The limits of subjective territorial

jurisdiction in the context of cybercrime. In ERA

Forum. 19. pp. 375-390.

Megret, F., 2020. “Do Not Do Abroad What You Would

Not Do at Home?”: An Exploration of the Rationales

for Extraterritorial Criminal Jurisdiction over a State’s

Nationals. Canadian Yearbook of international Law. In

Annuaire canadien de droit international. 57. pp. 1-40.

Peterson, Z.N.J., Gondree, M., Beverly, R., 2011. A

Position on Data Sovereignty: The Importance of

Geolocating Data in the Cloud. In HotCloud,

Proceedings of the 3

rd

USENIX conference of Hot topic

in Cloud computing. pp. 1-5.

Ring, T., 2021. Europol: the Al hacker threat to biometrics.

In Biometric Technology Today. 2. pp. 9-11.

Schomburg, W., Lagodny, O., 2020. Internationale

Rechtshilfe in Strafsachen. In International

Cooperation in Criminal Matters. KOMMENTAR. 6.

pp. 53.

Sieber, U., 2012. Straftaten und Strafverfolgung im

Internet. In Gutachten C zum 69. DEUTSCHEN

JURISTENTAG. pp. 112.

Zając, D., 2020. Criminal Jurisdiction over the Internet:

Jurisdictional Links in the Cyber Era. In Cambridge

Law Review. 4(2). pp. 1-28.

Countering the Cybercrimes: Problems of Criminal Law and Criminal Intelligence Operations at the International Level

139