“Robot Steganography”: Opportunities and Challenges

Martin Cooney

a

, Eric J

¨

arpe

b

and Alexey Vinel

c

School of Information Technology, Halmstad University, Halmstad, Sweden

Keywords:

Steganography, Robots, Autonomous Vehicle, Socially Assistive Robot, Speculative Prototyping.

Abstract:

Robots are being designed to communicate with people in various public and domestic venues in a perceptive,

helpful, and discreet way. Here, we use a speculative prototyping approach to shine light on a new concept

of robot steganography (RS): that a robot could seek to help vulnerable populations by discreetly warning

of potential threats: We first identify some potentially useful scenarios for RS related to safety and security–

concerns that are estimated to cost the world trillions of dollars each year–with a focus on two kinds of robots,

a socially assistive robot (SAR) and an autonomous vehicle (AV). Next, we propose that existing, powerful,

computer-based steganography (CS) approaches can be adopted with little effort in new contexts (SARs), while

also pointing out potential benefits of human-like steganography (HS): Although less efficient and robust than

CS, HS represents a currently-unused form of RS that could also be used to avoid requiring a computer to

receive messages, detection by more technically advanced adversaries, or a lack of alternative connectivity

(e.g., if a wireless channel is being jammed). Some unique challenges of RS are also introduced, that arise

from message generation, indirect perception, and effects of perspective. Finally, we confirm the feasibility

of the basic concept for RS, that messages can be hidden in a robot’s behaviors, via a simplified, initial user

study, also making available some code and a video. The immediate implication is that RS could potentially

help to improve people’s lives and mitigate some costly problems, as robots become increasingly prevalent in

our society–suggesting the usefulness of further discussion, ideation, and consideration by designers.

1 INTRODUCTION

At the crossroads between human-robot interaction

and secure communications, this design paper focuses

on the emerging topic of “robot steganography” (RS),

the hiding of messages by a robot.

Steganography is a vital way for vulnerable popu-

lations and their protectors to secretly seek help; e.g.,

encryption alone cannot prevent an adversary from

detecting that a message is being sent, which could

result in retribution. Such messages could also be

sent by interactive robots, which are expected to play

an increasingly useful role in the smart cities of the

near future by conducting dangerous, dull, and dirty

tasks, in a scalable, engaging, reliable, and perceptive

way. Here “robot” is defined generally as an embed-

ded computing system, comprising sensors and actua-

tors that afford some semi-autonomous, intelligent, or

human-like qualities. This comprises common tropes

like socially assistive robots (SARs; robots that seek

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4998-1685

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9307-9421

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4894-4134

to help people through social interactions), as well as

systems that we might not normally think of as robots,

such as autonomous vehicles (AVs), smart homes, and

wearables (i.e., robots that we ride, live in, and wear),

which exhibit qualities conducive for steganography:

• Generality. Since robots typically contain com-

puters, existing computer-based steganography

(CS) approaches can be used.

• Multimodality. Robots can generate various sig-

nals, from motions to sounds, that could also en-

able “human-like” steganography (HS).

• Opacity. Robots tend to be complex, such that

most people do not understand how they work.

• Nascency. Robots are not yet common in every-

day human environments due to their current level

of technological readiness, which could allow for

occasional odd behavior to be overlooked (plausi-

ble deniability).

However, currently it is unclear how a robot can

seek to accomplish good via steganography; thus,

the goal of the current paper is to explore this gap:

Section 2 positions our proposal within the litera-

200

Cooney, M., Järpe, E. and Vinel, A.

“Robot Steganography”: Opportunities and Challenges.

DOI: 10.5220/0010820300003116

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2022) - Volume 1, pages 200-207

ISBN: 978-989-758-547-0; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

ture, guiding our approach in Section 3, which iden-

tifies two key scenarios related to indoor and outdoor

robots. The core premise in both scenarios, that mes-

sages can also be hidden in robot motions and sounds,

is then verified via a simplified user study reported

in Section 4, followed by discussion in Section 5.

Thereby, the aim is to stimulate thought about the pos-

sibilities for robots to help people in the near future.

2 RELATED WORK

Steganography approaches could be applied by robots

that are intended to be perceptive, intelligent, and con-

textually appropriate. This relates to a recent pro-

posal that interactive robots should not always single-

mindedly reveal truth, but will need to “lie” in various

situations, to provide good service (Wagner, 2016;

Isaac and Bridewell, 2017). For example, a robot

asked by its owner about their weight might not wish

to respond, “Yes, you are very fat”.

Toward this goal, some relevant behavioral ap-

proaches and concerns have been identified: Inter-

dependence theory has been applied, suggesting that

stereotypes can be used to initially estimate the cost,

value, and estimated success rate of lying (Wagner,

2016). Theory of mind has been espoused as a way

to allow robots to detect ulterior motives, to avoid

manipulation by humans with bad intentions (Isaac

and Bridewell, 2017). Additionally, a system was

developed to detect human lies based on eye move-

ments, response times, and eloquence, also verify-

ing that robots were lied to in a similar way as hu-

mans (Gonzalez-Billandon et al., 2019). Such work

has formed a basis for robots to interact more effec-

tively via discreet communication.

We believe that for similar reasons, not just false

utterances, but also an ability to send secret messages

to the right recipient via steganography could be use-

ful. Here, we propose that RS can be considered to

comprise two broad categories, HS and CS:

2.1 Human-like Steganography (HS)

Since ancient times, humans have used a variety of

audiovisual signals (Petitcolas et al., 1999) to warn of

threats, ask for help, signal action, or even to just sur-

reptiously poke fun at others. Similarly, a robot could

blink in Morse code or use gestures to warn of tor-

ture,

1, 2

and draw symbols like black dots, use a red

1

www.archives.gov/exhibits/eyewitness/html.php?

section=8

2

www.damninteresting.com/the-seizing-of-the-pueblo/

pen, or utter safe keywords like “Angela” or “Mino-

taur”, to warn of domestic violence.

3, 4, 5

Robots could

also leverage common everyday media tropes, from

gestures such as putting “bunny ears” behind some-

one’s head when a photo is taken, to facial expres-

sions behind someone’s back, or using a bird call to

signal an ally without alerting adversaries. One recent

study has started to examine a similar case for how an

underwater vehicle could mimic animal sounds (Jia-

jia et al., 2018), yet studies related to HS appear to

be strikingly rare–possibly due to the nascent state of

robotic technology, as well as some salient advantages

of CS, discussed next.

2.2 Computer-based Steganography

(CS)

The development of computers led to new possibil-

ities for highly efficient and robust steganography,

typically involving small changes to little-used, re-

dundant parts of a digital carrier signal. For ex-

ample, least significant bits (LSB), parity bits, or

certain frequencies can be used, in a carrier such

as digital text, visual media (image, video), audio

(music, speech, sounds), or network communications

(communicated frames/data packets) (Zieli

´

nska et al.,

2014). In particular, the latter is starting to be ex-

plored for robots; for example, de Fuentes and col-

leagues investigated CS in Vehicular Ad hoc Net-

works (VANETs) (de Fuentes et al., 2014). Our anal-

ysis suggested that, although CS has strong advan-

tages, there could still be a use for HS, since CS re-

quires a device to receive messages, is more likely

to be known to adversaries, and could be prevented

by disabling or jamming wireless communications.

However, what was unclear was how a robot can use

HS or CS to help people.

Toward starting to address this gap, we have pre-

viously reported in a short paper on some initial ideas

regarding vehicular steganography (Cooney et al.,

2021). The novel contribution of the current paper,

which extends the latter, is in exploring the “big pic-

ture” for RS, including opportunities and challenges.

3 METHODS

To explore the lay of the land, we adopted a specu-

lative prototyping approach that seeks to capture po-

3

www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-34326137

4

themighty.com/2020/01/domestic-violence-prevention-

sign-red-marker/

5

canadianwomen.org/signal-for-help/

“Robot Steganography”: Opportunities and Challenges

201

tentially important, plausible, and thought-provoking

scenarios in a concrete, easily-understood way, as

well as to test some part of the challenges that emerge

in a simplified user study (Dunne and Raby, 2013; En-

gelberg and Seffah, 2002).

Thus, in line with the “How Might We” design

method, rapid ideation sessions were first conducted

within the group, asking the question: How might a

robot help people by sending secret messages? Brain-

storming ideas were recorded without judgement,

then blended and grouped into short written narra-

tive scenarios. The aim was to capture a wide range

of ideas in a small number of potentially high-value,

plausible, uncertain, and different scenarios. Feasi-

bility from the perspective of current technology was

not used as a filter, given the speculative approach;

i.e., our initial concern was not how robot capabilities

could be implemented (such as the rich recognition

capabilities that will be required) but what could be

useful. This resulted in a total of eight initial sce-

narios, which were then analyzed, yielding insight

into some core themes: the kinds of problems that

would be useful to design solutions for, commonali-

ties, venues, interactive roles, cues to detect, and ac-

tions a robot could take, as well as some unique chal-

lenges.

Furthermore, two example scenarios were se-

lected, for two kinds of robot: a socially assistive hu-

manoid robot (SAR) and an autonomous vehicle (AV).

The former is an indoor robot with a focus on social

communication, especially for healthcare, whereas

the latter is an outdoor robot with a focus on locomo-

tion and transport; both offer exciting possibilities for

improving quality of life in interacting persons. The

example scenarios are presented below:

SAR. “Howdy!” called Alice, the cleaning robot at

the care center, as she entered Charlie’s room. Her

voice trailed off as she took in the odd scene in front

of her: Charlie appeared agitated, and she could see

bruises on his arms. The room was cold from an open

window, which had probably been opened hours ago,

and yesterday’s drinks had not been cleared away–

there was no sign that anything had been provided

for breakfast. Closing the window, Alice noticed a

spike of “worry” in her emotion module, directed to-

ward Charlie, whom she knew had a troubled rela-

tionship with Oliver, his main caregiver. The other

day, Charlie had acted disruptively due to his late-

stage dementia. To this, Oliver had expressed frus-

tration and threatened punishment; with his history

of crime, substance abuse, unemployment, and men-

tal health problems, this might not be merely an idle

threat. But, there might be some explanation that Al-

ice didn’t know about, and she didn’t have permission

to contact authorities, since a false report could have

highly negative consequences. Sending a digital mes-

sage would also probably not be wise, since the mat-

ter was urgent, and Oliver and the rest of the group

had access to her logs. When she headed over to

the reception, there was Oliver talking to Bob. Alice

wanted to let Bob know as soon as possible without

alerting Oliver, so she surreptitiously waved to Bob

behind Oliver’s back to get his attention and flashed

a message on her display that she would like to ask

him to discreetly check in on Charlie as soon as pos-

sible. Bob nodded imperceptibly, and Alice went back

to cleaning. With Bob’s help, Alice was sure that

Charlie would be okay.

AV. “Hey!” KITTEN, a large truck AV, inadvertently

exclaimed. “Are you watching the road?” Her driver,

Oscar, ignored KITTEN, speeding erratically down

the crowded street near the old center of the city with

its tourist area, market, station, and school, which

were not on his regular route. KITTEN was wor-

ried about Oscar, who had increasingly been show-

ing signs of radicalization–meeting with extremists

such as Mallory–and instability, not listening to vari-

ous warnings related to medicine non-adherence, de-

pression, and sleep deprivation. But she wasn’t com-

pletely sure if Oscar was currently dangerous or im-

paired, as his driving was always on the aggressive

side; and, KITTEN didn’t want to go to the police–if

she were wrong, Oscar might lose his job. Or, even if

she were right and the police didn’t believe her, Os-

car could get angry and try to bypass her security fea-

ture, or find a different car altogether, and then there

would be no way to help anymore. At the next in-

tersection, KITTEN decided to use steganography to

send a quick “orange” warning to nearby protective

infrastructure, comprising a monitoring system and

anti-tire spikes that can be raised to prevent vehicles

from crashing into crowds of pedestrians–while plan-

ning to execute an emergency brake and call for help

if absolutely required.

The scenarios suggested that RS might be useful

when two conditions hold:

• There is a High Probability of Danger. If the

robot is not completely sure about the threat, or

has not been given the right to assess such a threat

as the consequences of a mistake could be ex-

tremely harmful, the robot could require another

opinion, possibly through escalation to a human-

in-the-loop. In particular, this could occur when

there is a possibility of an accident or crime: Traf-

fic accidents are globally the leading killer of peo-

ple aged 5-29 years, with millions killed and in-

jured annually

6

, and crimes are estimated to cost

6

www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565684

ICAART 2022 - 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

202

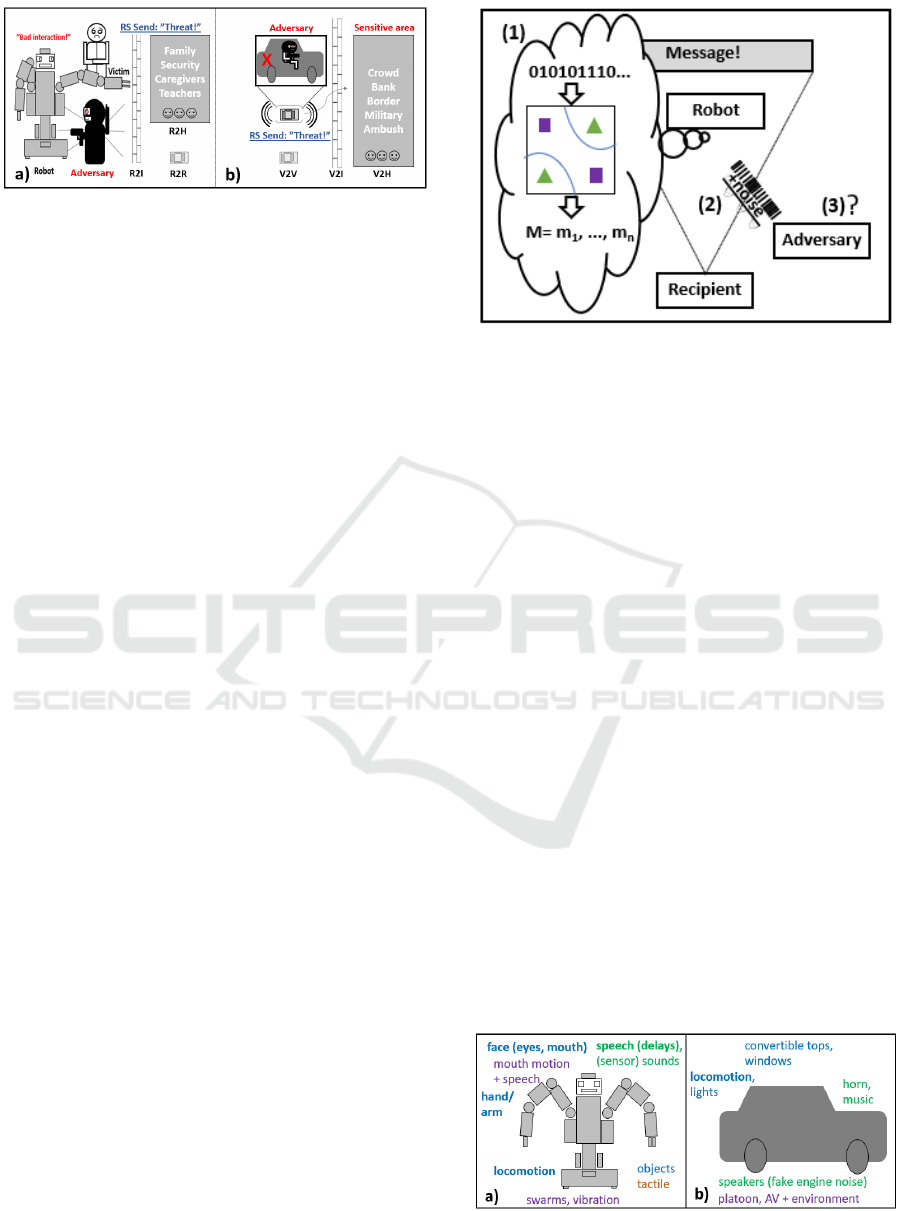

Figure 1: Scenarios: (a) SAR. Someone might require pro-

tection from an undesirable interaction, (b) AV. A possible

threat is approaching a sensitive area.

trillions of dollars each year (DeLisi, 2016).

• Conventional Communication is Undesirable.

If direct messages might be detected (e.g., in logs

or by monitoring wireless traffic), message hiding

could be a way to reduce the risk of reprisals and

exacerbating the problem. The intended recipient

might also not have a computer, or there might

be a lack of connectivity preventing a robot from

communicating a problem–with or without covert

properties (e.g., because an adversary jammed the

wireless channel).

It should be clear than an adversary could com-

pletely block any communications from a robot,

by shutting it off, destroying it, abandoning it, or

modifying it to either not send messages or send

false messages. However, we believe that adver-

saries will not do this in various cases, if a robot

is not seen to interfere (e.g., by sending uncon-

cealed messages): Disabling a robot could call un-

wanted attention to an adversary, in the same way

as restraining any nearby humans. There might be

many robots and devices in the vicinity. The robot

could be still perceived as useful for some purpose

(e.g., an AV carrying the adversary). And, people

are accustomed to using technologies that could

be used against them for convenience, from cam-

eras that could be used for monitoring, to vehicles

that could cause a deadly accident.

Thus, alternatives exist: RS (CS, HS), encryption

only, or direct communication. When the above con-

ditions do not hold, a different approach than RS can

be used; for example, a robot could directly call for

help if it has witnessed a life-threatening situation and

the threat is perfectly clear, like if shots have been

fired–or if the robot has a strong belief that the adver-

sary could not detect a call for help.

A detailed comparison of scenarios for SARs and

AVs, including settings, informative cues, and poten-

tial robot actions, is presented in Table 1, and the gist

is visualized in Fig. 1.

Additionally, the scenarios also suggested some

“unique” aspects to RS that differ from traditional

Figure 2: Unique challenges of robot steganography (RS):

(1) message generation, (2) indirection, (3) perspective.

steganography, as shown in Fig. 2:

• Generation. Instead of humans coming up with

messages to send over computers, an AV must it-

self generate a message from sensed information.

• Indirection. In HS, files are not passed di-

rectly from sender to recipient, introducing risks

of noise and lower data transmission rates.

• Perspective. In HS, unlike e.g., video motion

vector steganography, a robot could control its

motion to generate an anisotropic message visi-

ble only at some specified angle and distance; au-

dio reception could also be controlled via “sound

from ultrasound” (Pompei, 2002) or high fre-

quency to send location- or age-specific sounds.

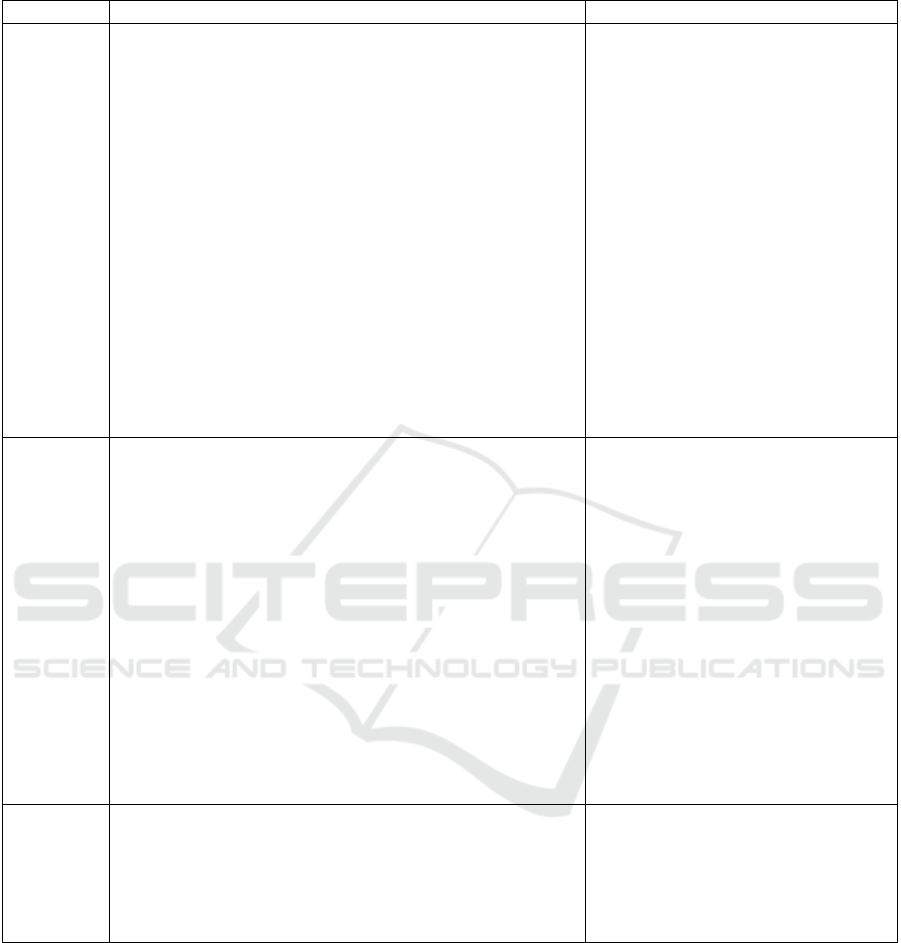

Furthermore, various audiovisual carriers could

be used for HS, as shown in Fig. 3: Visu-

ally, locomotion–e.g., variance over time in posi-

tion and orientation (path, or trajectory), velocity,

or acceleration–could be used to hide messages de-

tectable via communicated GPS, videos, or odome-

try; other visual signals could include lights, opening

or closing of windows, and convertible tops. Aurally,

speakers that generate engine noise (like soundak-

tors), or even music players or a horn could be used.

More complex approaches could be multimodal, us-

ing a platoon, swarm of drones, or even the environ-

Figure 3: Carriers: (blue) visual, (green) audio, (purple)

multimodal, (brown) other.

“Robot Steganography”: Opportunities and Challenges

203

Table 1: Some fundamental concerns for RS with SARs and AVs.

SARs AVs

Scenarios SARs could help with preventing the potential abduction,

abuse, or homicide of vulnerable populations such as el-

derly, children, persons with special needs (e.g., demen-

tia, autism, blindness, motor impairment, depression),

homeless persons, spouses, or members of some targeted

group (e.g., whistleblowers, freedom fighters, persecuted

minorities, or prisoners). The main case considered here

was a direct threat from a human adversary. Typically, an

adversary might seek private access to a victim (e.g., via

removal to a second location) to avoid abuse being wit-

nessed; intentions could include domestic violence, kid-

napping, bullying, assault, robbery, threat, murder, mi-

croaggression, retribution, battery, or rape–within transi-

tional, secluded, or dangerous settings such as a care cen-

ter, school, home, bar, night club, store, lot, station, street

or park. The robot could be accompanying a person, or

just happen to be in the area to conduct some other task,

such as healthcare, cleaning, or delivery.

An AV could be involved in reckless

driving (hit-and-run, drunk driving),

trafficking (drugs, humans or other

contraband), robbery (at a bank,

store, or carjacking), or violent

crime (homicide or abduction). Typ-

ically, an adversary (a lone individ-

ual, small group, or representative

of an oppressive nation) might ex-

hibit malevolent cues during transit

to a sensitive area such as a bor-

der, bank, military site, or crowded

or dangerous location. The main

case considered involved a direct

threat from a human adversary trav-

elling inside the AV, although ex-

ternal adversaries (humans or AVs)

could also be detected.

Cues Indicators could include: (1) Sudden negative or odd

changes in a potential victim’s state or behavior (includ-

ing physical signs such as bruises; emotional displays of

pain, fear, or anger; or behavioral subservience). Such

cues could potentially be detected via anomaly or change

point detection, during monitoring of health, emotions,

and activities. (2) High risk factors such as violent, un-

justified behavior or emotional displays from a poten-

tial adversary, especially if there is a large perceived

force imbalance, possibly in conjunction with a history of

fighting, threats, crime, substance abuse, unemployment,

high stress, and mental health problems. Violent be-

havior could be detected via cameras, microphones, and

touch sensors on a SAR or in the environment, whereas

historic data could be accessed from police or medical

records.

Targets for detection could include

speeding, weaving, tailgating, and

failing to yield or signal, in man-

ual driving mode–and more gen-

erally, hiding packages; unhealthy

behavior (medicine non-adherence

with depression or sleep depriva-

tion); and being armed and masked

without occasion. Problematic driv-

ing could be detected from surveil-

lance camera data; health problems

by collating data from electronic pill

dispensors and smart homes; and

threatening gear from cameras in-

side an AV.

Actions Warnings could be sent to family such as parents, secu-

rity, teachers, or care staff (R2H), as well as doors or ve-

hicles (R2I and R2R), while also potentially preventing

the victim from being taken away by lying about where-

abouts, stalling, and evading.

Warnings could be sent to border

or bank security (V2H), protective

infrastructure (e.g., anti-tire spikes;

V2I), or nearby AVs or platoon

members (V2V), while also poten-

tially seeking to delay or obstruct.

ment, like birds flying plus an AV’s motion; use rare

modalities like heat; or use delays, ordering, modality

selection, and amplitudes.

Implementations could leverage various work that

has looked at how robots can perceive signals and or-

ganize knowledge (e.g., based on Semantic Web lan-

guages like W3C Web Ontology Language (OWL)),

and information can be embedded in a message as

bits or pulses using a code such as ASCII, Morse,

or Polybius squares. Message generation could po-

tentially be formalized as a Knapsack problem, and a

steganographic force could be added to a Social Force

model to design motions incorporating messages, al-

though details for these ideas cannot be given within

the scope of this paper.

4 USER STUDY

To fully realize the speculative scenarios in the pre-

vious section, various advanced capabilities will be

required, but the main premise for RS–that messages

ICAART 2022 - 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

204

can be hidden in a robot’s motions and sounds in a

way that is not easy to detect by potential adversaries–

seemed to require some immediate verification. Thus,

to check the basic feasibility of this idea, a small user

study was conducted, based on implementing some

simplified algorithms. Of the two example scenarios,

we wanted to focus on one for our initial prototyping,

and to develop an actual physical prototype where

real-world problems might emerge, rather than a sim-

ulation; since an error with an AV could be lethal,

we selected the basic idea of the SAR scenario for

our first exploration. In this scenario, a SAR, Alice,

uses RS to send various messages to a protector, Bob,

in such a way that an adversary, Oliver does not see

them.

4.1 Participants

20 faculty members and students at our university’s

School of Information Technology participated in an

online survey (40% were female, 50% male, and 10%

preferred not to say; average age was 41.8 years with

SD= 10.3; and six nationalities were represented, with

Swedish by far the most common (60%)). Partic-

ipants received no compensation. Ethical approval

was not required for this study in accordance with the

Swedish ethics review act of 2003 (SFS no 2003:460),

but principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and Gen-

eral Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) were fol-

lowed: e.g., in regard to written informed consent.

4.2 Procedure

Similar to our previous study on audio steganogra-

phy (J

¨

arpe and Weckst

´

en, 2021), participants were

sent links to a Google Forms survey, which took ap-

proximately three minutes to complete. Participants

played the part of the adversary, watching two pairs of

videos of a SAR moving and speaking. In one video

of each pair, messages were hidden in the robot’s

behaviors, toward saving a new victim, Stacey. Af-

ter watching each pair of videos, participants noted

which one they thought contained a hidden message.

For safety and simplicity, the Baxter robot was used,

which is a SAR that is easily programmed to commu-

nicate audiovisually via movements, a face display,

and speech utterances.

4.3 Conditions

Two conditions were used, steganography (present or

absent) and modality (visual or audio), based on our

analysis of channels that can be used for HS. Thus,

four videos (two pairs) were prepared, as depicted in

Figure 4: Audiovisual steganography was applied to (a) vi-

sual signals (gripper motions, facial display, arm motions),

as well as (b) sounds (speech delays and WAV files).

Fig.4. Both of the steganography videos featured ex-

amples of both CS and HS.

Visual Steganography: The first two videos showed

the robot greeting an adversary, who has suddenly ap-

peared. (The videos were recorded from the adver-

sary’s perspective.) The steganography video used

three visual carriers to send hidden messages to an

off-camera observer to the left, intended to be diffi-

cult to perceive by the adversary. The robot initially

appeared as if it is vacuum cleaning, while opening

and closing a gripper to express “SOS” through Morse

code to the off-camera observer; the gripper’s motion

and clicking sound were masked via its other arm–

demonstrating the perspective property–and the vacu-

uming sound. Next, the robot raised its arm in greet-

ing, during which arm angles specified as floats were

recorded in a motion file and constantly published on

Robot Operating System (ROS) channels; there, an

ASCII message, “SOS”, was embedded in the LSB.

Also, the ASCII message “SOS! Stacey needs your

help!” was hidden in the image data used for the

robot’s face via LSB. Thus, the messages were con-

veyed via “pure” HS (not requiring a computer to de-

tect), HS closer to CS (a human-like motion, but re-

quiring a computer to read), and CS. It wasn’t clear if

participants might notice strangeness in the clicking

of the gripper, vibrations due the concealed motion,

or the roughness in the robot’s arm motion due to the

added message.

Audio Steganography: The second pair of videos

showed a robot speaking to an adversary. The

steganography video used two audio carriers to hide

messages. Speech utterance delays were used to hide

the message “SOS” in a “simplified” Morse code

(100ms dot, 200ms dash). The message is read by

using the sounddevice library to detect volume, with

a model of normal delays–exemplifying the indirec-

tion property. Some simple heuristics were used in-

cluding hysteresis in volume for speech start and end,

and a model for the minimal length of a speech sound.

Furthermore, the ASCII message “SOS! Stacey needs

your help!” was again hidden, in the LSB of a WAV

“Robot Steganography”: Opportunities and Challenges

205

file which the robot uses to say “hello”. Thus, the sig-

nals were predominantly HS and CS, respectively. It

wasn’t clear if participants might notice extra delays

or roughness in the steganography condition.

The reason that transmission is hidden in this case

is that a SAR is expected to use its display, motions,

and sounds to interact–normally there is no suspicion

that such behaviors have any other hidden commu-

nicative purpose.

4.4 Results

If the robot was successful at hiding messages, the

rate at which participants could identify the videos

with hidden messages should have been around ran-

dom chance (50%). Else, if the robot failed to hide

its messages, the rate should have been higher (e.g.,

closer to 100%).

In this study, participants guessed the file with the

hidden messages 55% and 50% of the time (11 and

10 participants respectively; thus, 21 out of 40 times,

or 52.5%, where 19 out of 40 times, or 47.5%, the

guesses were wrong). A binomial test confirmed that

this success rate was not more common than can be

expected by random chance (50%), for the results

of the first pair of videos (p = .8), the second pair

(p > .9), and all of the data together (p = .9). In

other words, the robot had performed as we had ex-

pected. Also, of 13 participants who left comments,

ten explicitly stated that they could not see obvious

differences and guessed; three indicated cues such

as nodding, color changes, pauses and blinking that

could not be clearly related to changes expected due

to embedding messages, possibly a result of parei-

dolia (a human tendency to see patterns even where

none exist). No participant correctly identified cues

that might have resulted from adding the hidden mes-

sages.

Thus, our hypothesis was supported, and this sim-

plified check confirmed that messages can be suc-

cessfully concealed in some common robot behaviors

without humans suspecting. While some messages re-

quire the recipient to have a computer, others, like the

robot’s gripper communicating via Morse code, can

be seen by the naked eye.

5 DISCUSSION

In summary, the contribution of the current work is

proposing some theoretical and practical considera-

tions for a robot to convey hidden messages to help

people, which we have dubbed robot steganography

(RS):

• A speculative approach revealed

– applications to traffic safety and crime preven-

tion

– three unique qualities of RS relating to message

generation, indirection, and perspective

– potential carriers, as well as initial ideas for sig-

nal generation.

• A simplified, initial user study confirmed that

messages can be hidden in various robot behav-

iors, also demonstrating a first example of RS.

• Additionally, a video and code have been made

freely available to help guide others who might be

interested in this topic.

7, 8

As robots become increasingly prevalent, the re-

sults suggest the usefulness of further discussion and

ideation around RS, which could potentially help save

people’s lives and could be easily implemented in

some contexts: Robots can already use established

approaches for computer-based steganography (CS)

to communicate with computers, robots, or humans

equipped with computers. Moreover, human-like RS

(HS) can also be used to communicate even with hu-

mans who do not have access to a computer (e.g., this

can be as simple as merely gesturing or displaying a

message behind someone’s back), when technically

capable adversaries might be aware of more common

CS approaches, or when conventional CS channels

are obstructed. Furthermore, as noted, RS can com-

plement other techniques such as encryption or lying.

5.1 Limitations and Future Work

This work represents only an initial investigation into

a few topics related to RS and is limited by its na-

ture, comprising speculation and simplified prototyp-

ing approach. It should be stressed that it is neither

possible, nor the goal of the current paper, to fully de-

scribe and test all RS methods that could exist, or to

fully realize the scenarios identified. Other important

scenarios, carriers, and motion generation approaches

might exist for other kinds of robots, and the simpli-

fied user study only checked the feasibility of RS in

a prototype SAR–much more work will be required

to realize RS in the real world. As well, the degree to

which RS will be useful is not yet completely clear, as

both CS and HS can result in lower transmission rates

than merely encrypting or sending direct communica-

tions, which might not be justified if intended recipi-

ents are expected to always be monitoring a computer

7

youtu.be/vr3zlva6cCU

8

github.com/martincooney/robot-steganography

ICAART 2022 - 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

206

or adversaries are expected to never be technically ca-

pable.

Future work will also explore allostatic (preventi-

tive) interventions, steganalysis (detection of hidden

messages), ethics, and perception of dangerous sce-

narios. For example, could robots use conversation or

touch to defuse situations, making adversaries less an-

gry and victims feel safer and better (Akiyoshi et al.,

2021)? Will an ability to help people via RS, con-

ducting vicarious inference and showing empathy, fa-

cilitate acceptance of robots and positive long-term

interactions (Lowe et al., 2019)? By shining light on

such questions, we aim to bring a fresh perspective to

possibilities for robots to create a better, safer society,

which could also facilitate acceptance and trust in the

use of robots in our everyday lives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank our colleagues who participated in scenario

building or the user study!–and gratefully acknowl-

edge support from the Swedish Knowledge Founda-

tion (KKS) for the SafeSmart “Safety of Connected

Intelligent Vehicles in Smart Cities” Synergy project

(2019–2023), the Swedish Innovation Agency (VIN-

NOVA) for the “Emergency Vehicle Traffic Light Pre-

emption in Cities – EPIC” project (2020–2022) and

the ELLIIT Strategic Research Network.

REFERENCES

Akiyoshi, T., Nakanishi, J., Ishiguro, H., Sumioka, H., and

Shiomi, M. (2021). A robot that encourages self-

disclosure to reduce anger mood. IEEE Robotics and

Automation Letters, 6(4):7925–7932.

Cooney, M., J

¨

arpe, E., and Vinel, A. (2021). “Vehicu-

lar Steganography”?: Opportunities and Challenges.

Electronic Communications of the EASST, 80.

de Fuentes, J. M., Blasco, J., Gonz

´

alez-Tablas, A. I., and

Gonz

´

alez-Manzano, L. (2014). Applying information

hiding in VANETs to covertly report misbehaving ve-

hicles. International Journal of Distributed Sensor

Networks, 10(2):120626.

DeLisi, M. (2016). Measuring the cost of crime. The hand-

book of measurement issues in criminology and crim-

inal justice, pages 416–33.

Dunne, A. and Raby, F. (2013). Speculative everything:

design, fiction, and social dreaming. MIT press.

Engelberg, D. and Seffah, A. (2002). A framework for rapid

mid-fidelity prototyping of web sites. In IFIP World

Computer Congress, TC 13, pages 203–215. Springer.

Gonzalez-Billandon, J., Aroyo, A. M., Tonelli, A., Pasquali,

D., Sciutti, A., Gori, M., Sandini, G., and Rea, F.

(2019). Can a robot catch you lying? a machine learn-

ing system to detect lies during interactions. Frontiers

in Robotics and AI, 6:64.

Isaac, A. M. and Bridewell, W. (2017). Why robots need to

deceive (and how). Robot ethics, 2:157–172.

J

¨

arpe, E. and Weckst

´

en, M. (2021). Velody 2—Resilient

High-Capacity MIDI Steganography for Organ and

Harpsichord Music. Applied Sciences, 11(1):39.

Jia-jia, J., Xian-quan, W., Fa-jie, D., Xiao, F., Han, Y., and

Bo, H. (2018). Bio-inspired steganography for secure

underwater acoustic communications. IEEE Commu-

nications Magazine, 56(10):156–162.

Lowe, R., Alm

´

er, A., Gander, P., and Balkenius, C.

(2019). Vicarious value learning and inference in

human-human and human-robot interaction. In 2019

8th International Conference on Affective Comput-

ing and Intelligent Interaction Workshops and Demos

(ACIIW), pages 395–400. IEEE.

Petitcolas, F. A., Anderson, R. J., and Kuhn, M. G. (1999).

Information hiding-a survey. Proceedings of the IEEE,

87(7):1062–1078.

Pompei, F. J. (2002). Sound from ultrasound: The para-

metric array as an audible sound source. PhD thesis,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Wagner, A. R. (2016). Lies and deception: Robots that

use falsehood as a social strategy. Robots that talk

and listen: Technology and social impact. De Grutyer

https://doi. org/10.1515/9781614514404.

Zieli

´

nska, E., Mazurczyk, W., and Szczypiorski, K. (2014).

Trends in steganography. Communications of the

ACM, 57(3):86–95.

“Robot Steganography”: Opportunities and Challenges

207