Organizational Toughness in Clothing Industry during

Covid-19 Pandemic

João M. S. Carvalho

1,2,3 a

and Sílvia Faria

1b

1

REMIT, Universidade Portucalense, R. António Bernardino de Almeida, 541 – 4200-072 Porto, Portugal

2

CEG, Universidade Aberta, Lisboa, Portugal

3

CICS.NOVA, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

Keywords: Organizational Toughness, Organizational Plasticity, Organizational Strength, Strategic Management,

Economic and Social Sustainability, Clothing Sector.

Abstract: Today, the existence of natural (earthquakes, pandemics, etc.) and human (large strikes, revolutions, etc.)

events that can lead to economic paralysis are more and more frequent. Thus, it is not surprising that

researchers try to develop new concepts and theories to explain the phenomena' reality. It is the case of a new

conceptual approach – organisational toughness – that can give us insights into an organisation's capacity to

survive in turbulent environmental contexts, like this of the Covid-19 pandemic. This study aimed at analysing

the survival capability of the Portuguese clothing sector, in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, through a

new tool to measure organisational toughness. A sample of 106 organisations was studied using a

questionnaire, leading to the conclusion that the measurement tool is effective, reliable and valid for that

purpose, contributing to helping entrepreneurs to be able to assess crucial management variables to face this

type of crisis. Theoretical and practical implications were taken, highlighting the importance of other concepts

like organisational plasticity and organisational strength as the main factors to face new market threats and

opportunities, impacting companies' economic and social sustainability.

1 INTRODUCTION AND

FRAMEWORK

It is known that any organisation is subject to multiple

risks (e.g., financial, technological, market,

competitive, reputational, political, economic),

namely a systemic risk related to the possibility to

occurring a pandemic, a terrorist threat, natural

disasters, or strikes in sectors of activity that

immobilise one’s business. Thus, the government can

prevent an organisation from working in emergency

or catastrophe situations to avoid contagion or

physical damage to workers. Another cause to stop

production could be the absence of supplies or loss of

their facilities. Wenzel, Stanske, and Lieberman

(2020) reviewed the papers published in the journals

of the Strategic Management Society and concluded

that there would be four ways for organisations to

respond to this crisis: retrenchment, persevering,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0683-296X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7672-3972

innovating, and exit. Beyond these possible strategic

responses, Carvalho (2020) proposed the

organisational toughness model, trying to explain

which could be the main factors that organisations

should take care more attentive to increase their

chance of survival. This approach is interesting

because it followed a research stream that adopted

concepts about the properties of materials studied in

physics to explain business phenomena. It is the case

with the concepts of resilience as the ability of a

material to absorb energy when it is deformed

elastically, being a combination of strength and

elasticity (e.g., Holbeche, 2019; Walker & Salt,

2006); flexibility as the ability of an object to bend or

deform in response to an applied force (e.g., Reed &

Blunsdon, 1998); plasticity as the ability of a material

to undergo irreversible or permanent deformations

without breaking or rupturing (e.g., Avey, Palanski,

& Walumbwa, 2011; Gavetti & Rivkin, 2007; Hill,

Cromartie, & McGinnis, 2017); and toughness as the

Carvalho, J. and Faria, S.

Organizational Toughness in Clothing Industry during Covid-19 Pandemic.

DOI: 10.5220/0010919800003206

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2022), pages 15-21

ISBN: 978-989-758-567-8; ISSN: 2184-5891

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

15

ability of a material to absorb energy or withstand

shock and plastically deform without fracturing,

being a combination of strength and plasticity (e.g.,

Carvalho, 2020). The advantage of this concept of

organisational toughness is the acceptance that during

these turbulent periods, the companies, besides their

capacity to absorb shocks and adjust to them in a

plastic way, may also become different and better

adapted to future turbulent periods. This approach

was somehow foreseen by Holbeche (2019) when she

talked about organisational resilience, defining it as

the robustness of the organisational systems and a

response capacity to a disruptive environment.

However, resilience means flexibility and plasticity,

leading the organisation to adjust itself to the external

shock in an elastic way but later return to what it was

before that market turbulence. Thus, we think that

what this author has defined is better described by the

concept of organisational toughness, presented by

Carvalho (2020) in a more precise way, respecting the

original physics approach.

Therefore, this model was based on literature and

pointed out the importance of staff preparation,

internal structure adapted to change, and internal and

external availability of resources to face those

exogenous shocks. Each of these constructs presents

literature support:

(1) Staff preparation was based on workers’

flexibility (Bhattacharya, Gibson, & Doty, 2005;

Wright & Snell, 1998), competencies (Eldridge &

Nisar, 2006; Plonka, 1997) and motivations (e.g.,

Kreye, 2016; Locke & Schattke, 2019).

(2) A structure adapted to change and all types of

contingencies (e.g., Holbeche, 2019; Uhl-Bien &

Arena, 2018) asks for a versatile and agile leadership

(Keister, 2014), flexible strategic planning to timely

develop adaptive and/or innovative processes

(Carvalho, 2018; Ivory & Brooks, 2018), and market-

oriented organizational learning (e.g., Camps et al.,

2016; Edwards, 2009; Levinthal & Marino, 2015).

(3) Internal and external availability of resources

was based on the resource-based theory (Penrose,

1959; Wernerfelt, 1984), seeing an organization as a

bundle of resources and capabilities (e.g., Beltrán-

Martín et al., 2009; Bhattacharya et al., 2005; Ngo &

Loi, 2008) that also depends on its environment for

those resources (Sheppard, 1995).

As such, Carvalho (2020) defined organizational

plasticity as the ability of an organization to change

irreversibly and permanently its strategic approach to

the markets to survive and/or grow (resilience), under

different environment conditions (adaptability) and

pressures (flexibility), and be able to timely and

effectively (agility) react to threats and proactively

seize opportunities (p.4); and organizational strength

as “the ability of an organization to access internal

and external physical, human, intellectual and

financial resources” (p.11).

However, this author did not provide any

guidance about how the variables of the model might

be measured in his seminal article, besides the fact

that he stated five propositions that assumed

organisational toughness, organisational plasticity,

organisational strength, staff preparation, and

structure adapted to change as latent variables; and

competencies, motivation, flexibility, strategic

planning, leadership, market-oriented organisational

learning, internal availability of resources, and

external availability of resources as manifest

variables. Nevertheless, it is possible to see this

potential model as integrating formative rather than

reflective items, creating a way to directly and

approximately measure each construct. In this way,

any company will assess its strength, plasticity and

toughness to face public health situations or others

that may jeopardise its survival. This is our approach

to this model, proposing the possibility that it includes

only formative variables, which theoretically makes

sense, and that facilitates its application by any

entrepreneur in practical life. Additionally, we added

a new variable to the model – economic and social

sustainability – measured by economic performance

and social impact items. This assessment is crucial to

measure other variables impact on the results and

performance of the organisations during the

pandemic. These concepts of sustainability appeared

after the first approach related to ecological

sustainability (WCED, 1987). Elkington (1997)

presented the triple bottom line – people, planet, and

profit –– as the pillars of sustainability. Other authors

talked about sustainable entrepreneurship (e.g.,

Kuckertz & Wagner, 2010) and sustainable

innovations (Khavul & Bruton, 2013), considering

the preservation and enhancement of the natural

environment, business ecosystems through the

satisfaction of human needs with the available

resources as a condition to the financial sustainability

of the organisations, social cohesion (e.g., well-being,

nutrition, shelter, health, education, quality of life),

and psychological balance (e.g., positive emotional

states, physical and mental health, and personal

perception of quality of life (European Commission,

2011). For this study, we decided to use only

economic and social sustainability questions, as we

have thought that these were the main concerns for

the entrepreneurs during this pandemic period.

Based on these assumptions, one presented the

following hypotheses:

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

16

H1: Organizational Plasticity (OP) could be measured

by Staff Preparation (SP), and Structure Adapted

to Change (SAC).

H2: Organizational Toughness (OT) could be

measured by Organizational Plasticity and

Organizational Strength (OS).

H3: Organizational Plasticity has a greater impact on

Organizational Toughness than Organizational

Strength.

H4: Organizational Toughness has a positive impact

on Economic and Social Sustainability (ESS).

We have created new measures for these variables in

order to analyse the survival capability of the

Portuguese clothing sector, in the context of the

Covid-19 pandemic.

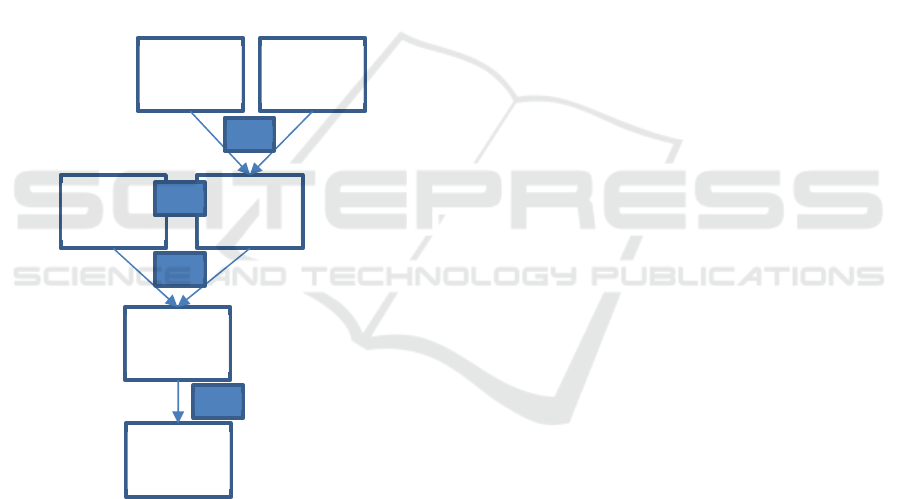

1.1 The Model

The proposed recursive model is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1: The organisational toughness model.

2 METHODS

Several references were consulted to decide the best

way to conduct this exploratory study (e.g., DeVellis,

2012; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998;

Malhotra et al., 2012; Netemeyer, Bearden, &

Sharma, 2003). Consequently, we followed eight

sequential steps: (a) creation of an initial pool of items

based on the literature review and six experts; (b)

analysis of this pool by six field experts that

subsequently chose the items they considered to be

more adapted to the constructs, and trying to be

parsimonious as possible in their choice; (c) creation

of a questionnaire that includes the chosen items and

some questions to characterise the respondents; (d)

pretesting of the questionnaire; (e) creation of the

final version of the questionnaire to apply to all

organisations of the clothing sector; (f) data

collection; (g) data analysis; (h) analysis of the

proposed model and validity of the hypotheses.

Besides the 30 questions to measure the variables,

the questionnaire included questions about sex, age,

and hierarchical position of each participant. Data

analysis was performed with SPSS, v.26. and AMOS,

v.26.

2.1 Participants

We used a database (https://sabi.bvdinfo.com/) that

has information from 800 thousand Portuguese

organisations. We chose the Clothing Industry (Code

of Economic Activity - 14) because it had a

tremendous impact from the pandemic, like many

other activity sectors. There were 822 companies

registered, but we discovered that 115 of them went

bankrupt before 2020 and 53 during that year. Thus,

654 companies in this sector remained that we have

contacted twice by email because we had the names

and electronic addresses of their owners and/or top

managers. Nevertheless, 82 emails were returned

because they were no longer active, which led our

sample to be reduced to 572 companies. The response

rate of 18.5% (106 participants) is understandable

because many companies may be closed entirely or

working on minimal services.

The sample is characterised as follows: 48 female

(45.3%) with an average age of 39.17 (SD = 9.01),

and 58 (54.7%) male with an average age of 50.86

(SD = 11.54), being 52 (49.1%) owners of the

companies, and 54 (50.9%) top managers.

2.2 Variable Measures

All the items in the questionnaire were based on the

literature (Table 1). Malhotra et al. (2012) defended

“that a tailor-made short scale with a modest number

of items might be a better choice as it balances the

cost constraints and information needed to cover key

facets of the construct” (p.843). This approach allows

obtaining high-quality survey responses and

sufficient information for theory building and

practical implication (e.g., Richins, 2004; de Jong et

al., 2009).

Staff

Preparation

Structure

adapted to

change

Organization

Plasticity

Organizational

Strength

Economic and

Social

Sustainability

Organization

Toughness

H1

H2

H3

H4

Organizational Toughness in Clothing Industry during Covid-19 Pandemic

17

The answer to the questions was performed on a

Likert’s five-point scale: 1 – I absolutely disagree; 2

– I disagree; 3 – I neither disagree nor agree; 4 – I

agree; and 5 – I absolutely agree. The questionnaires

were pretested with 11 top managers to verify the

reliability of their interpretation, being made some

adjustments in the wording of the questions.

Table 1: Final items to measure the variables.

Variables Items

Internal

availability of

resources

1. The company has always had the necessary number of staff to

be able to work normally.

2. The company has always had enough raw materials available

internally to be able to work normally.

3. We were able to recombine the internal available resources in

new forms of organization in order to continue working.

External

availability of

resources

4. We always had a supply of raw materials to be able to work

normally.

5. We had easy access to outside labour, so that we could

continue to work normally.

6. We had easy access to finance to be able to continue working

normally (not including State aid, if it had happened).

Strategic

planning

7. There is, formally, a strategic plan that foresees difficult

contingencies in the market, as a result of strikes, pandemics or

potential catastrophes.

8. All personnel, to the extent of their responsibilities, contributed

to carry out the strategic plan.

9. Our strategic planning process is flexible, and easily adapts to

new market conditions.

Leadership

10. The leadership in the company is agile in adjusting the

company to new market contingencies.

11. The dominant leadership style of our managers is more

reactive than proactive. *

12. Our managers take into account that normal work situations

can be totally changed from day to day, knowing how to adjust

work teams quickly.

Market-

oriented

organizational

learning

13. We learn quickly from mistakes when we fail to approach

markets.

14. We sufficiently research the needs of our current or potential

customers.

15. We have frequent training to develop our skills and serve our

customers better, even in crisis situations.

Competences

16. All managers and employees have a high level of skills,

knowledge and experience.

17. Not all managers and employees have a high capacity to adapt

quickly and constantly to new work environments. *

18. All managers and employees are quick to solve problems,

share information and knowledge, and work as a team.

Motivation

19. Our managers and employees have high levels of internal

motivation, feeling very satisfied in their functions.

20. Our managers know how to motivate company employees,

even in the most difficult situations.

21. Our employees feel positively challenged when difficulties at

work increase.

Flexibility

22. Our managers and employees are flexible enough about their

roles and what needs to be done for the company to succeed.

23. The distribution of our human resources in quantity and

quality is relatively difficult in our company. *

24. Our managers and employees feel able to face any difficulties

that may arise in the markets.

Economic

performance

25. Even in a crisis, our economic and financial performance was

excellent.

26. We achieved a higher sales volume than expected.

27. The breakdown in the business put the company's survival at

risk. *

Social impact

28. We manage to maintain all jobs in the company.

29. Our customers continued to be served, namely through online

purchase and sale processes.

30. We managed to innovate and create new products and

services that were very useful for the community in which we

operate.

* Reversed items

The score for each manifest variable was obtained by

calculation of the mean of their respective items.

Items 11, 17, 23 and 27 needed to reverse their

punctuation.

Some variables follow a normal distribution (IAR,

EAR, SP, and M), and others are relatively close. We

decided to keep the outliers because they represent

real situations, and the sample is already short.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To test the first hypothesis (Organizational

Toughness could be measured by Organizational

Plasticity and Organizational Strength), we have

conducted an exploratory factor analysis on the

independent manifest variables, using a Principal

Axis Factoring with a Varimax rotation (Table 2). All

indicators showed good values for factor analysis:

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin statistic = 0.75; and Bartlett Test

of Sphericity that showed that the variables are

suitable for this type of analysis (Approx. Chi-Square

= 362.8; df = 28; p < 0.001). The determinant of the

R-matrix of correlations (D = 0.055) was used to test

multicollinearity, which should be greater than

0.00001 to show the absence of its excess. Also, the

matrix of reproduced correlations showed less than

50% of its values greater than 0.05 (8 [28%]), which

shows that the model does fit the data significantly.

The result presented two factors that match the

constructs of Organizational Plasticity and

Organizational Strength before and after rotation,

explaining 66.11% of the total variance and 55.7% of

shared variance.

Table 2: Exploratory factor analysis of Organizational

Toughness.

Variables

Factors

Organizational

P

lasticit

y

Organizational

Strength

Strategic planning 0.528

Leadership 0.576

Market-oriented organizational learning 0.755

Competences 0.728

Motivation 0.794

Flexibility 0,855

Internal availability of resources 0.712

External availability of resources 0.731

The two factors presented good reliability,

measured by the alpha of Cronbach, as well as

convergent and discriminant validity, assessed by the

fact that the compositive reliability (CR) is sufficient

higher and the average of variance extracted (AVE)

is higher than 0.5 and higher than the square

correlation between the variables (Table 3). However,

this result did not explicitly discriminate between

Staff Preparation and Structure Adapted to Change.

Thus, the first hypothesis is not validated.

Nevertheless, all the variables of these two aspects

contribute to the construct of Organizational

Plasticity, which leads us to validate the second

hypothesis.

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

18

Table 3: Assessment of the measures of Organizational

Toughness.

Variables

Indicators

α

CR AVE R

2

Or

g

anizational Stren

g

th 0.738 0.685 0.521

OS – OP

(0.043)

Or

g

anizational Plasticit

y

0.849 0.860 0.512

Common method variance (CMV) was assessed

by Harman's single factor test and Marker variable

techniques, which showed that CMV did not

significantly impact the correlation between OT and

ESS. This test presented three factors (70.61% of total

variance), with the first one accounting for less than

50% (42.4%) of the total variance (Podsakoff &

Organ, 1986). The marker variable technique allows

controlling CMV (Lindell & Whitney, 2001).

According to these authors, we used the second

smallest positive correlation among the manifest

variables (0.039) to control CMV. Then, we have

calculated the CMV‐adjusted correlation between

the variables, concluding that the spurious correlation

caused by the CMV amounts just to 0.034, all

correlations being equally statistically significant.

The third (Organizational Plasticity has a greater

impact on Organizational Toughness than

Organizational Strength) and fourth hypotheses

(Organizational Toughness has a positive impact on

Economic and Social Sustainability) can be assessed

by regression analysis. In each model, it is possible to

evaluate variable collinearity, ensuring that this is not

a problem to the result analysis. One can see in table

4 the results of three regression analyses. It is possible

to verify that we did not have concerns about

multicollinearity because tolerance and variance

inflation factor is near 1, or lower than the most

exigent VIF threshold of 2.5 defended by Johnston et

al. (2018).

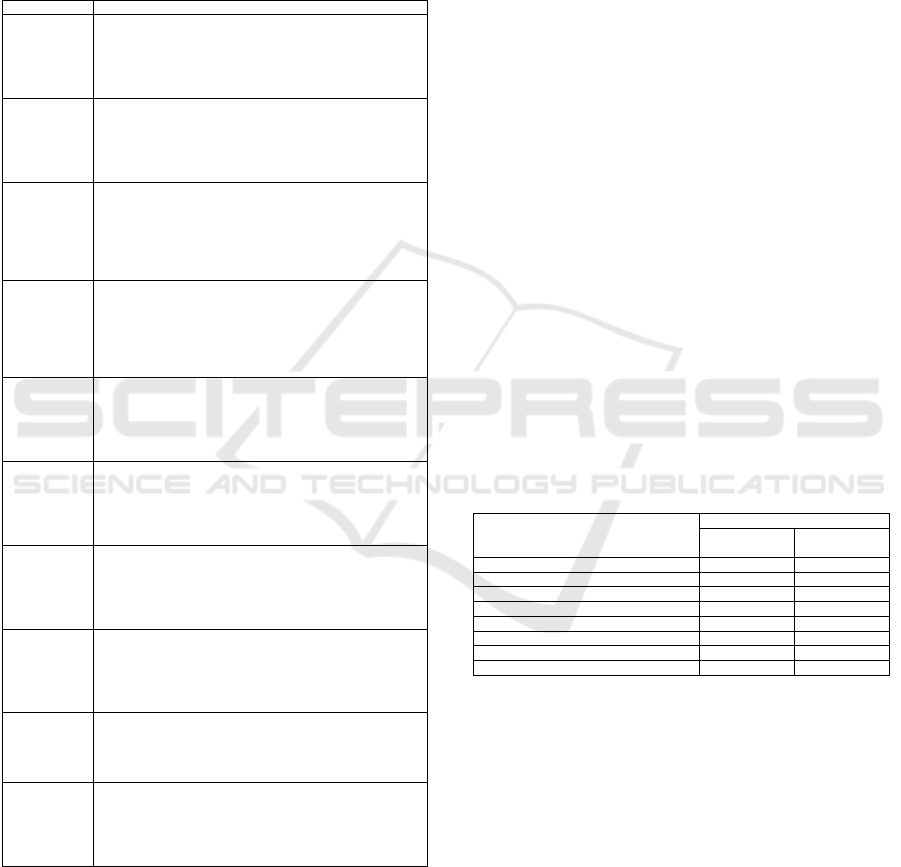

Table 4: Regression analysis on Economic and Social

Sustainability.

Models Variables

Indicators

B

Std.

error

β Tolerance VIF

1 OT 0.776 0.132 0.499*** 1.000 1.000

2

OS 0.179 0.084 0.175* 0.957 1.045

OP 0.786 0.124 0.520*** 0.957 1.045

3

OS 0.180 0.083 0.176* 0.957 1.045

SAC 0.523 0.168 0.345** 0.509 1.963

SP 0.285 0.144 0.221* 0.505 1.982

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Thus, we can conclude for the validation of the H3

and H4: the impact of Organizational Plasticity is

greater than the impact of Organizational Strength on

Economic and Social Sustainability; and it exists a

positive and statistically significant impact of

Organizational Toughness on Economic and Social

Sustainability. Also, this result allowed to show that

criterion-related validity exists because the

independent variables showed the expected

relationships.

More, if we use the two constructs based on

Organizational Plasticity (Model 3), we can notice

that a Structure Adapted to Change has the highest

impact on ESS, followed by Staff Preparation and

Organizational Strength. The first two impacts were

already predicted in the literature (e.g. Basadur et al.,

2014; Bhattacharya et al., 2005; Ketkar & Sett, 2010),

as well as the third one (e.g., Beltrán-Martín et al.,

2009; Bhattacharya et al., 2005; Ngo & Loi, 2008).

Of course, the companies with higher workers’

competencies, motivation, and flexibility presented

more success. It may mean that in this activity sector,

what was considered more important to survive was

the flexibility of their strategic planning, the

leadership in the company, and to learn quickly with

the context to be more adaptable to the market.

Finally, it seems that most of the companies did not

have too many problems with their supplies, probably

because they are used to adjusting fast to new orders

at any time, which is very common in this activity

sector (Truett & Truett, 2019).

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study aimed to analyse the survival capability of

the clothing sector Portuguese companies in the

context of the Covid-19 pandemic. Based on a

published theoretical model about organisational

toughness (Carvalho, 2020), we developed a

questionnaire containing a parsimonious number of

items to assess all the constructs. Based on the

literature and experts’ opinions, the questions looked

to measure constructs like the levels of internal and

external availability of resources, strategic planning,

leadership, market-oriented organisational learning,

competencies, motivation, flexibility, economic

performance, and social impact. These variables are

formative of broader and new concepts like

organisational strength, organisational plasticity,

organisational toughness, and economic and social

sustainability. All these proxies worked very well,

capturing what had happened in the companies of the

clothing sector.

As such, we conclude that organisational strength

and plasticity inform what is called organisational

toughness. This construct presents a positive and

significant impact on economic and social

sustainability during the Covid-19 pandemic. These

results imply some practical insights, which

reinforces previous knowledge, but in a new extreme

Organizational Toughness in Clothing Industry during Covid-19 Pandemic

19

context. More, these turbulent environments can

occur in other contexts, like natural catastrophes,

large strikes, revolutions, etc., which can lead to

economic paralysis. Thus, it is crucial for companies’

survival that they be prepared in terms of logistics of

their resources to continue to produce. For instance, a

just-in-time strategy would be disastrous in these

types of contexts. Additionally, the companies’

owners or managers should develop an organisational

culture that considers a market-oriented perspective

to learn how to be close to the clients’ needs in any

environment. These situations call for flexible

strategic planning, adjusted leadership, and effective

personal recruitment and training that properly

comprehends the needed competencies, motivation,

and flexibility to address turbulent times or

unexpected events.

Thus, this study contributes to management

theory because it presents a new model that highlights

the crucial role of organizational toughness,

composed of organizational plasticity and

organizational strength, to assure economic and social

sustainability during high turbulent times.

This study presents some limitations, namely

those related to the gathering of data in the Covid-19

period and the exploratory character of the survey.

Although the sample is sufficient to obtain credible

results, it is still made up of companies that were

available to respond to the survey in that period, i.e.

the generalization to the population of companies in

the sector should take this fact into account.

Nevertheless, we think these concepts could be

studied in other contexts, activity sectors, and

countries. They are exciting and new in the literature,

helping researchers and practitioners to think more

closely about what might matter in times of great

turmoil in the economies and the world.

REFERENCES

Avey, J. B., Palanski, M. E., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2011).

When leadership goes unnoticed: The moderating role

of follower self-esteem on the relationship between

ethical leadership and follower behavior. Journal of

Business Ethics, 98, 573–582. doi:10.1007/s10551-

010-0610-2

Basadur, M., Gelade, G., & Basadur, T. (2014). Creative

problem-solving process styles, cognitive work

demands, and organizational adaptability. The Journal

of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(1) 80–115.

doi:10.1177/0021886313508433

Beltrán-Martín, I., Roca-Puig, V., Escrig-Tena, A, & Bou-

Llusar, J. C. (2009). Internal labour flexibility from a

resource-based view approach: definition and proposal

of a measurement scale. The International Journal of

Human Resource Management, 20(7), 1576–1598.

doi:10.1080/09585190902985194

Bhattacharya, M., Gibson, D. E., & Doty, D. H. (2005). The

effects of flexibility in employee skills, employee

behaviors, and human resource practices on firm

performance. Journal of Management, 31(4), 622-640.

doi:10.1177/0149206304272347

Camps, J., Oltra, V., Aldás-Manzano, J., Buenaventura-

Vera, G., & Torres-Carballo, F. (2016). Individual

performance in turbulent environments: The role of

organizational learning and employee flexibility.

Human Resource Management, 55(3), 363–383.

doi:10.1002/hrm.21741

Carvalho, J. M. S. (2018). The Ties of Business. A

humanistic perspective of entrepreneurship, innovation

and sustainability. Lambert Academic Publishing.

Carvalho, J. M. S. (2020). Organizational toughness facing

new economic crisis. European Journal of

Management and Marketing Studies, 5(3), 156-176.

doi:10.46827/ejmms.v5i3.873

de Jong, M. G., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Veldkamp, B. P.

(2009). A model for the construction of country-

specific yet internationally comparable short-form

marketing scales. Marketing Science, 28, 674–689.

doi:10.1287/mksc.1080.0439

DeVellis, R. F. (2012). Scale development. Theory and

applications. London: Sage Publications Inc.

Edwards, M. G. (2009). An integrative metatheory for

organizational learning and sustainability in turbulent

times. The Learning Organization, 16(3), 189–207.

doi:10.1108/09696470910949926

Eldridge, D., & Nisar, T. M. (2006). The significance of

employee skill in flexible work organizations.

International Journal of Human Resource

Management, 17(5), 918-937. doi:10.1080/0958519

0600641164

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with Forks: The Triple

Bottom Line of Twenty-First Century Business. Oxford,

UK: Capstone.

European Commission. (2011). Mental Well-Being: For a

Smart, Inclusive and Sustainable Europe. A paper to

present first outcomes of the implementation of the

‘European Pact for Mental Health and Well-being’.

Retrieved January 15, 2015, from http://ec.europa.eu/

health/mental_health/docs/outcomes_pact_en.pdf

Gavetti, G., & Rivkin, J. W. (2007). On the origin of

strategy: Action and cognition over time.

Organization

Science, 18(3), 420–439. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0282

Hair, J. F. Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W.

C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. New York, NY:

MacMillan.

Hill, M. E., Cromartie, J., & McGinnis, J. (2017). Managing

for variability: A neuroscientific approach for

developing strategic agility in organizations. Creative

Innovation Management, 26, 221–232. doi:10.1111/c

aim.12223

Holbeche, L. (2019). Designing sustainably agile and

resilient organizations. Systems Research and

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

20

Behavioral Science, 36, 668–677. doi:10.1002/

sres.2624

Ivory, S. B., & Brooks, S. B. (2018). Managing corporate

sustainability with a paradoxical lens: Lessons from

strategic agility. Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 347–

361. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3583-6

Johnston, R., Jones, K., & Manley, D. (2018). Confounding

and collinearity in regression analysis: A cautionary

tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies

of British voting behaviour. Quality & Quantity:

International Journal of Methodology, 52(4), 1957–

1976. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0584-6

Keister, A. C. (2014). Thriving teams and change agility:

leveraging a collective state to create organization

agility. In A. Shani & D. A. Noumair (Eds.), Research

in Organizational Change and Development (pp. 299-

333). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Ketkar, S., & Sett, P. K. (2010). Environmental dynamism,

human resource flexibility, and firm performance:

Analysis of a multi-level causal model. International

Journal of Human Resource Management, 21, 1173–

1206. doi:10.1080/09585192.2010.483841

Khavul, S., & Bruton, G. D. (2013). Harnessing Innovation

for Change: Sustainability and Poverty in Developing

Countries. Journal of Management Studies, 50(2), 285–

306. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01067.x

Kreye, M. E. (2016). Employee motivation in product

service system providers. Production Planning &

Control, 27, 15, 1249-1259. doi:10.1080/095372

87.2016.1206219

Kuckertz, A., & Wagner, M. (2010). The influence of

sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions

— Investigating the role of business experience.

Journal of Business Venturing, 25(5), 524–539.

doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.09.001

Levinthal, D., & Marino, A. (2015). Three facets of

organizational adaptation: Selection, variety, and

plasticity. Organization Science, 26(3), 743-755.

doi:10.1287/orsc.2014.0956

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for

common method variance in cross‐sectional designs.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 114 – 121.

doi:10.1037//0021-9010.86.1.114

Locke, E. A., & Schattke, K. (2019). Intrinsic and extrinsic

motivation: Time for expansion and clarification.

Motivation Science, 5(4), 277–290. doi:10.1037/

mot0000116

Malhotra, N. K., Mukhopadhyay, S., Liu, X., & Dash, S.

(2012). One, few or many? An integrated framework

for identifying the items in measurement scales.

International Journal of Market Research, 54(6), 835-

862. doi:10.2501/IJMR-54-6-835-862

Netemeyer, R. G., Bearden, W. O., & Sharma, S. (2003).

Scaling procedures. Issues and applications. London:

Sage Publications Inc.

Ngo, H.-Y., & Loi, R. (2008). Human resource flexibility,

organizational culture and firm performance: an

investigation of multinational firms in Hong Kong. The

International Journal of Human Resource

Management, 19(9), 1654–1666.

Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Plonka, F. S. (1997). Developing a lean and agile work

force. Human Factors and Ergonomics in

Manufacturing, 7

(1), 11–20. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-

6564(199724)7:1%3C11::aid-hfm2%3E3.0.co;2-j

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self‐reports in

organizational research: Problems and prospects.

Journal of Management, 12(4), 531 – 544.

doi:10.1177/01492 06386 01200408

Reed, K., & Blunsdon, B. (1998). Organizational flexibility

in Australia. International Journal of Human Resource

Management, 9(3), 457–477. doi:10.1080/09585199

8341017

Richins, M. L. (2004). The material values scale:

measurement properties and development of a short

form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 209–219.

doi:10.1086/383436

Sheppard, J. (1995). A resource dependence approach to

organizational failure. Social Science Research, 24, 28–

62. doi:10.1006/ssre.1995.1002

Truett, L. J., & Truett, D. B. (2019). Challenges in the

Portuguese textile and clothing industry: a fight for

survival. Applied Economics, 51(26), 2842–2854.

doi:10.1080/00036846.2018.1558362

Uhl-Bien, M., & Arena, M. (2018). Leadership for

organizational adaptability: A theoretical synthesis and

integrative framework. The Leadership Quarterly,

29(1), 89–104. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.009

Walker, B. H., & Salt, D. A. (2006). Resilience thinking:

sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing world.

Washington, D.C., USA: Island Press.

WCED – World Commission on Environment and

Development. (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford,

UK: Oxford University Press.

Wenzel, M., Stanske, S., & Lieberman, M. B. (2020).

Strategic responses to crisis. Strategic Management

Journal, Virtual Special Issue. doi:10.1002/smj.3161

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm.

Strategic Management Journal, 5, 171–180.

doi:10.1002/smj.4250050207

Wright, P. M., & Snell, S. A. (1998). Toward a unifying

framework for exploring fit and flexibility in strategic

human resource management. Academy of

Management Review, 23, 756-772. doi:10.2307/259061

Organizational Toughness in Clothing Industry during Covid-19 Pandemic

21