Formative Feedback in Mathematics Teacher Education: An Activity

and Affordance Theory Perspective

Said Hadjerrouit and Celestine Ifeanyi Nnagbo

a

Institute of Mathematical Sciences, Faculty of Engineering and Sciences, University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway

Keywords: Activity Theory (AT), Affordance Actualization, Affordance Perception, Affordance Theory,

Computer-based Assessment System, Constraint, Formative Feedback, Numbas.

Abstract: The increasingly high number of students’ enrolment has necessitated the recent attention on the use of

computer-based assessment systems for feedback delivery to students for mathematical learning, such as

Numbas. However, little is known about the affordances of Numbas in the research literature. The purpose of

this study is to investigate the affordances of Numbas, their perception and actualization by students and

teachers, and their effects on mathematical learning from an activity and affordance theory perspective. The

study follows a qualitative research design using semi-structured interviews of six students and two teachers.

The results reveal the perception and actualization of several affordances at the technological, mathematical,

and pedagogical level. Conclusions and future work are drawn from the results to promote Numbas formative

feedback for teaching and learning mathematics.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, emergent technologies like computer-

based assessment systems are gaining more attention

in mathematics education because they provide a

resource-efficient way to providing the much-needed

timely feedback to the students. Computer-based

assessment systems provide new learning potentials

for a large cohort of students by means of formative

and summative assessment. However, research on

computer-based assessment systems is still in its

infancy, especially in the area that assesses the added

value, affordances and constraints of such systems

(Csapó et al., 2012; Hadjerrouit & Nnagbo, 2021).

This study proposes a framework that captures the

affordances and constraints of Numbas in a

technology-based course at the University of Agder.

This study relates to previous research work on

affordances of Numbas in mathematics education

(Hadjerrouit & Nnagbo, 2021; Nnagbo, 2020). In

specific terms, the study aims to address the following

research questions:

1. What affordances of Numbas are perceived by

students and teachers?

a

C. I. Nnagbo defended his master’s thesis in mathematics

education in 2020 at the Institute of Mathematical Sciences,

University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway.

2. How are the perceived affordances of Numbas

actualised by students and teachers?

3. What are the constraints for the actualisation of

Numbas affordances by students and teachers?

2 NUMBAS

Numbas is a computer-based assessment system for

mathematics and mathematics-related courses with

emphasis on formative assessment and feedback

(Lawson-Perfect, 2015). The primary use of Numbas

is to enable students to enter a mathematical answer

in the form of an algebraic expression, and then see

how Numbas feedback can impact students’

mathematical learning. Numbas allows several

question-and-answer types such as mathematical

expression, number entry, matrix entry, match text

pattern, choose one or several from a list, match

choices with answers, gap-fill, information only, are

supported by Numbas. The system shows the notation

instantly beside the input field, so as students are

inputting their answers, simultaneously they see how

Hadjerrouit, S. and Nnagboa, C.

Formative Feedback in Mathematics Teacher Education: An Activity and Affordance Theory Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0010937800003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 2, pages 417-424

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

417

the tool understands their expressions. Numbas

provides several capabilities to users.

Ease of Integrating Rich Content Materials:

Numbas supports videos and interactive diagrams to

be embedded on the editor before they are distributed

along with the final questions. The videos can be

uploaded directly, while the interactive diagrams

could be included in Numbas questions either by

embedding a GeoGebra applet or use JSXGraph.

Marking: Numbas uses marking to mark

mathematical expressions. For example, in

factorizing a quadratic equation, expected answers

are often in this form (x+a)(x+b) and not x^2+ax+b,

but Numbas marking algorithm is capable to

understand the later form, mark correctly and give

feedback accordingly.

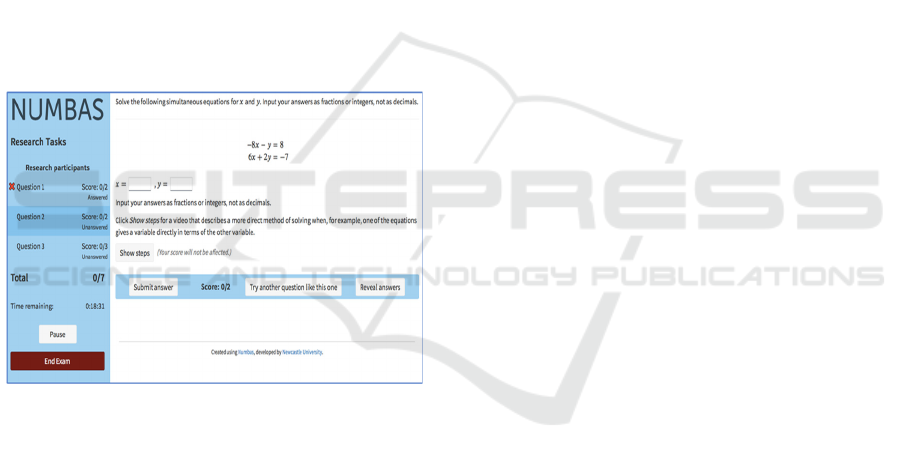

Feedback: Numbas makes its feedback

immediate. In order to make the feedback effective,

there are multiple ways Numbas gives feedback to

both students and instructors. These include the

following options: submit answer, show steps, reveal

answers, try another question like this one (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Feedback options.

Submit Answer: Students get feedback when

they submit an answer. The feedback indicates with a

green color ‘good’ sign if the answer is correct, with

red color ‘bad’ sign indicating that the answer is

wrong, or partially correct. The students will also be

shown the maximum attainable score for each

question, and their own score for the question after

they have submitted the answer. The teacher may

choose to disable these feedback options.

Show Steps: When “show steps” is chosen,

Numbas will give the general solution to that task.

This is a way of reminding the student to have a look

at the general solution and retry solving the task. This

does not give the exact solution to the particular task.

Try Another Question Like This One: With this

option, students have the opportunity to attempt

similar questions many times until they feel

confidence to move to the next question.

Reveal Answer: This option provides a step-by-

step solution that is personalized to the question, but

the students lose all the marks and cannot re-attempt

the exact question. This option may be disabled by

teachers.

Statistics: Numbas stores data of students’

performance. Teachers can track how well the

students understand the topic through their

performances, and they can equally identify the tasks

students perform below expectations and

reemphasize on them in the next class if necessary.

3 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Activity Theory (AT) is coupled with affordance

theory to form the theoretical framework of this

study. AT is found to be a source of useful concepts

for describing how Numbas interacts with other

elements of the learning context, including students,

teachers, and the physical environment (Day &

Lloyd, 2007).

AT is combined with affordance theory (Volkoff

& Strong, 2017) to explicate the concepts of

emergence, perception, actualisation, and effects of

Numbas affordances on teaching and learning

mathematics. More precisely: (a) The emergence or

existence of Numbas affordances; (b) The perception

of Numbas affordances; (c) The actualisation of

Numbas perceived affordances; and (d) The effects of

Numbas affordances on learning and teaching.

3.1 Activity Theory (AT)

AT has its root in the cultural-historical psychology

work of Vygotsky, Leont’ev, and Engeström. The

primary ideas of the theory rests on the social-cultural

perspective of learning in which learning is conceived

as an offshoot of a dynamic relationship between the

learner and the environment. With other words,

learning is an appropriation of knowledge through a

feedback relation between the learner and the

environment (Vygotsky, 1978).

A fundamental concept in AT is the word

‘activity’ itself (Engeström, 2014). Leont’ev (1978)

defines an activity as any purposeful interaction

between a subject (which could be an individual or

collective), and an object. Leont’ev (1978) further

describes activity as the most basic unit of life; that

subject and object have no noticeable properties if

there is no activity. Thus, when activity is not studied

and understood, it may be difficult to deduce how an

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

418

artefact affords a subject. The underlying assumption

of the theory is that an artefact or tool mediates the

interaction between subject and object to give the

desired outcome.

3.2 Affordance Theory

The term ‘affordance’ was proposed by James J.

Gibson to describe what the environment offers the

animal (Gibson, 1986, p. 127). He argues that

affordances (henceforth, in plural or singular form)

can be seen from the properties of the environment

that are relative to the animal in question. He further

stresses that affordances must be peculiar to the

animal they afford; not just any property of the

environment or whatever the environment can offer.

In the world of Human-Computer Interaction, the

term “affordance” (Norman, 1988) refers to a goal-

oriented action potential that emerges as result of

interaction between subjects (e.g., students and

teachers) and an object (e.g., Numbas). Affordance is

neither the property of an object in isolation nor that

of the subject. Instead, it emerges as an offshoot of a

dynamic relationship between the subjects (students

and teachers) and the object (Numbas). It is perceived

(i.e., students and teachers are aware of the existence

of the action potential of Numbas) in many ways and

actualized (i.e., students are able to turn the potential

of Numbas into action) to produce effect (i.e.,

feedback delivery) depending on many factors that

include Numbas platform, its user interface,

capability of the students and their level of

preparedness. Moreover, the actualization of Numbas

affordance is either facilitated by some enabling

conditions or mitigated by some constraints.

Given the emergence of Numbas affordances, it is

important to ask how the affordances are perceived.

As such, when students interact with Numbas to

facilitate feedback delivery on some mathematics

concepts they do so conveniently with the aid of the

technological features of the tool. During this process,

they become aware of the affordances that emerged

during the interaction in terms of feedback delivery.

The next issue is how they can actualize these

affordances. Affordance actualization is a process of

turning action potentials (affordances) into real

actions to bring an effect in using a particular tool

(Anderson & Robey, 2017; Bernhard et al., 2013). To

turn a possibility into an action, it is expected that the

user has the ability and capability to harness the

potential and there are enabling conditions to

facilitate the process. Affordance actualization may

vary from one individual to another because it is goal-

oriented and a process of specificity. Two or more

students may interact with Numbas and actualize (or

not) different affordances of the tool depending on

their respective individual differences and choices.

Moreover, it is expected that following the

actualization of Numbas affordances are some

effects, which may be “intended by the user and/or

those by the original creator of the artefact as well as

unintended effects” (Bernhard et al., 2013, p.6). Thus,

it is expected that when affordances are perceived and

actualized, then some effects are generated in terms

of feedback delivery to students.

Drawing on this view, Engeström (2014) asserts

that the subject of any activity system uses a

combination of both physical and psychological

tools. As such, the mediating artefact in the present

study is Numbas. It is important to remark that there

is a thin line between the mediating artefact (Numbas)

and the object (feedback delivery) in this study

because the former encloses the latter. Unlike,

physical classroom objects such as whiteboards and

pointers that are used to mediate learning content.

Therefore, it is argued that the outcome of a

dynamic interaction between the subject (e.g.,

student), the object (feedback delivery), and the

mediating artefact (Numbas) are the affordances of

Numbas. In other words, Numbas affordances are not

an exclusive property of the tool and not completely

determined by the subject. Instead, they emerge from

a dynamic interaction between the tool and the

subject. A key issue is that the interaction between the

subject and object is considered from a socio-cultural

perspective following the lines of thought of Gibson

(1986).

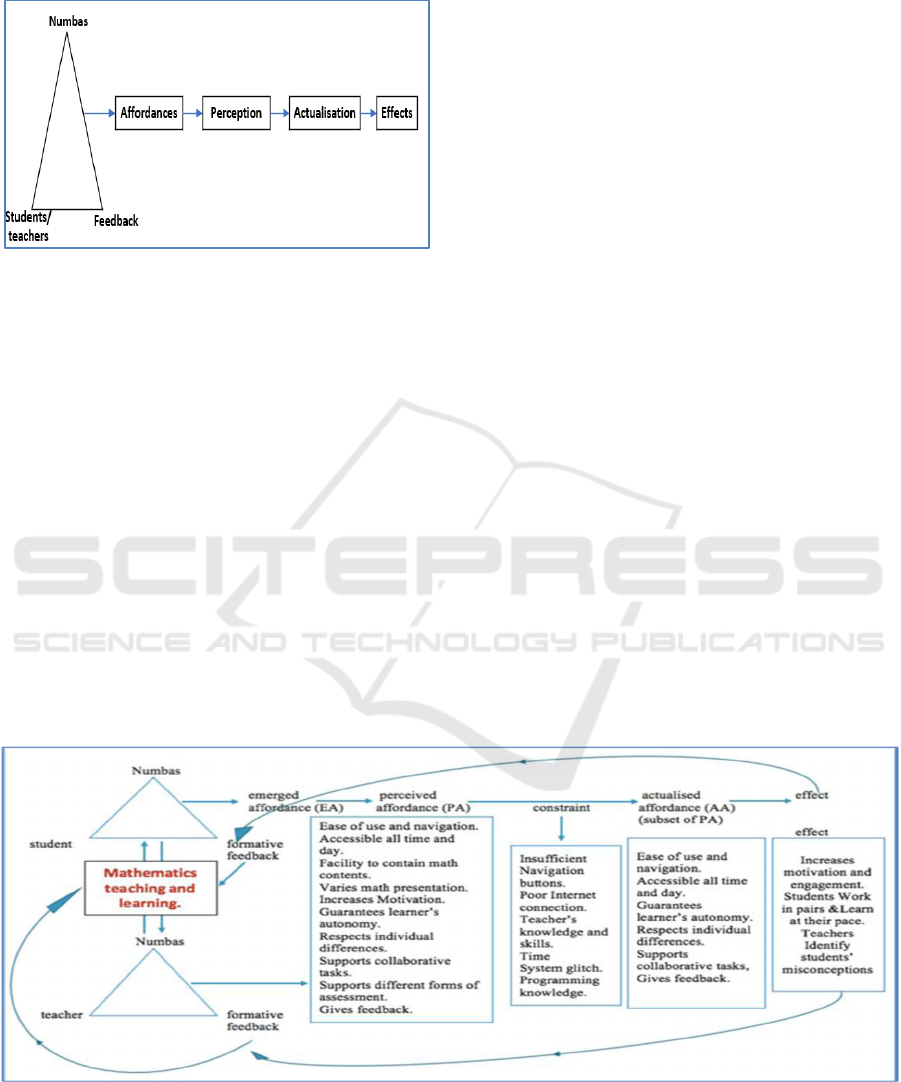

Figure 2 shows the theoretical framework that

captures the emergence, perception, and actualisation

of Numbas affordances, and their effect from an

activity theorical perspective. The perception of

Numbas affordances concerns its awareness by a

goal-oriented user during the interaction. Affordance

actualisation is a process of turning action potentials

(affordances) into real actions to bring an effect in

using a particular tool (Anderson & Robey, 2017;

Bernhard et al., 2013). In specific terms, affordance

actualisations are “the actions taken by actors as they

take advantage of one or more affordances through

their use of the technology to achieve immediate

concrete outcomes” (Strong et al., 2014, p. 70).

Moreover, it is expected that following the

actualisation of Numbas affordances are some effects.

It is important to highlight that actualisation of

Numbas affordances does not happen in isolation. In

fact, affordances are not without constraints; these are

facilitated by enabling conditions and hindered by

constraints. As captioned by Hadjerrouit (2020)

Formative Feedback in Mathematics Teacher Education: An Activity and Affordance Theory Perspective

419

affordances and constraints are inseparable because

they complement each other, and not opposite.

Figure 2: Perception, actualisation, and effects of Numbas

affordances from an Activity Theory perspective.

4 METHODS

A case study design approach (Yin, 2009) is chosen

to understand and analyze the affordances perceived

by both students and teachers while interacting with

Numbas, and how they actualize the perceived

affordances. Data collection was done from two set of

participants: Two teachers and six students from a

mathematics teacher education class of a Norwegian

university. The two teachers were considered and

selected because they are actively making use of

Numbas for formative assessment in their respective

classes. The second cohort is six out of about twelve

students from one class who willingly volunteered to

participate in the study. These participants are

master’s degree students taking a course entitled

“Digital tools in mathematics teaching”.

A thematic approach is used to analyze the data

by identifying themes or codes within the data set

(Bryman, 2016). The analysis takes both a deductive

and inductive approach by following the pre-defined

framework in search for meaningful interpretation of

the empirical data. Rom is given for the data to

express itself by creating new codes that emerge from

the data inductively. The development of codes

follows reading and rereading of the data carefully

and annotating same to identify topics, which are

refined and validated by checking whether these are

repeated or highlighted by different participants as an

important topic (Hennink et al., 2020).

5 RESULTS

Figure 3, which is an extension of figure 2, shows the

results achieved so far. The figure shows both

students’ and teachers’ activity systems in interaction,

and the affordances (and constraints) that emerged,

are perceived, and actualized, and their effects on

teaching and learning. Three types of affordances are

perceived: (a) Technological (e.g., ease-of-use and

navigation); (b) mathematical (e.g., varied

mathematical representations); and (c) pedagogical

(e.g., learner autonomy, motivation, formative

feedback, etc.). A subset of the perceived affordances

is actualized, and some of these have an effect on

teaching and learning. Space is limited to report on all

affordances. Therefore, the paper focuses on the three

types of affordances highlighted above.

Figure 3: Students’ and teachers’ activity systems in interaction, and the affordances that emerged, are perceived, actualized,

and their effects on teaching and learning.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

420

5.1 Technological Affordances

The findings reveal that both teachers and students

globally share the same views regarding

technological affordances. They perceived and

actualized affordances related to technological issues

such as ease-of-use and navigation, accessibility, and

facility to contain mathematical contents.

Regarding ease-of-use and navigation, one of the

students pointed out that “(…) anything you see there

is understandable; they are not complex. I think

everything is ok, I don’t have any problem with it. I

think the graphics are ok. It's just simple to use, there

are not much confusing buttons, every icon in the

interface is self-explanatory. It's just attractive”.

Another student added “the navigations were fairly

easy, the buttons are visible with good inscriptions,

just click on it and see what is inside. Like I said there

are not too many icons, so anywhere you want to

move to, it’s easy to find, and navigate there.”.

One of the teachers said: “it’s very much simple

to use, especially when compared with MyMathLab,

the main feedback from my students was that they

could see the mathematical expressions when they

write it in Numbas, they could see how the program

understands what they feed in, unlike in other

programs, so they committed fewer errors in Numbas

than in MyMathLab”.

The effect of ease-of-use and navigation is that

the students’ motivation and engagements increased;

they became curious and eager to solve more

formative assessment in Numbas.

The study finding clearly shows that the

perception of technological affordances such as

navigation and ease-of-use supports the perception of

and actualization of other affordances - which depend

to a large extent on the technological features of the

tool - such as learner autonomy, differentiation,

collaboration, and variation. If students or teachers

find the interface of Numbas difficult to use, they may

likely not use the tool to achieve their pedagogical

purpose. If the navigation buttons are hidden, the user

might not be able to move to the feedback pages,

thereby not getting the desired help.

However, reverse is the case when the teachers

themselves interacted with Numbas for the purpose of

creating tasks. Their responses seem to suggest that

creating tasks in Numbas is difficult, especially when

the task is a complex one. This can be seen from the

response given by one of the teachers "I will say that

could probably be better, once you start to getting the

grips on, I will say that using the basic things if you

want to create a simple task is quite easy, but again

as soon you start on more complicated questions, on

what to do more, (…), I will say it's not that intuitive

then you really need to go into the guidance because

there is a lot of boxes to check out if you want to do

that and you could".

Finally, the findings reveal some, mostly

technological constraints both for students and

teachers, such as insufficient navigation buttons, poor

internet connection when solving tasks, lack of

teachers’ knowledge and skills, e.g., programming

skills and lack of time for teachers.

5.2 Mathematical Affordances

Both teachers and students perceived the

mathematical affordance “varies mathematical

presentations”. With this affordance, teachers can

create formative assessment tasks using different

representations - diagrams, graphs, matrices, multiple

choices etc., also they can create the associated

feedbacks in various forms that may cover students’

misconceptions. Formative feedbacks that Numbas

give in these forms are found useful and motivating

by the teachers and students.

One of the students stated: “I think the

presentation of math contents in Numbas is of high

quality. Many things including graphs, diagrams,

videos, formulars, numbers, signs are well presented

…I think it's very nice”.

Another student suggested: “I have also come

across in Numbas some questions that contain

GeoGebra pages and graphs, that show how

sophisticated Numbas is, and that makes

presentations of mathematical contents really

pleasing”. Therefore, the possibilities of increased

variation, including supporting embedment of third-

party software, are high in using Numbas. The tool

was also found to be useful in terms of enhancing pen

and paper skills of students.

Likewise, another student indicated that “yes,

again as I said before, you often need your pen and

paper to do the calculations on Numbas. ...you have

to solve the tasks on paper especially the difficult

ones, by doing so, your pen and paper skills are

developing”.

The findings from the students’ perceptions are

similar to teachers’ views. One of the teachers thinks

that the “presentation of mathematical contents like

graphs, interactive diagrams, videos, GeoGebra

work well too... You can put in video and everything,

or link to YouTube channels or different pages and it

shows the video, you can play it within the program”.

Formative Feedback in Mathematics Teacher Education: An Activity and Affordance Theory Perspective

421

5.3 Pedagogical Affordances

Both teachers and students perceived and actualized

several pedagogical affordances, such as learner

autonomy, collaboration, differentiation, and in

particular formative feedback. Most perceived

affordances were actualized with effect on

motivation, engagement, learning and

misconceptions (see Figure 3).

Basically, formative assessment requires setting

learning and monitoring progress towards achieving

the goals. This type of feedback provision helps to

achieve learning goals. Similarly, Numbas feedback

gives the students the opportunity to access the level

they are in a learning process, what the learning goals

are, and how to achieve them. Findings reveal that

Numbas promotes formative assessment to both

students and teachers in a timely fashion in four

different forms:

a) It provides feedbacks to the teachers in form of

the statistical report of students’ activities

b) It provides support for students to test their

knowledge and exercises as much as they want

c) It helps students improve their learning, and

stay on track to meet their goals

d) It gives other types of feedbacks in different

forms, e.g., instant feedbacks, reveal answers,

show steps, or try another question like this one

Firstly, with statistical reports, time is saved for

teachers and students. From the teacher point of view,

the feedback in form of statistics containing students’

problem-solving strategies and ways of thinking

identifies their current performance level, areas of

difficulties and strengths are useful to the teachers for

conducting diagnostic teaching. Both teachers

expressed satisfaction with Numbas, particularly

because the tool is equipped with randomization

mechanisms, which means that it can generate

unlimited similar tasks with corresponding

feedbacks. This saves teachers a lot of time. They do

not need to spend days preparing tasks for formative

assessment. It also offers students the opportunity to

solve many tasks until they master the topic.

Secondly, teachers think that students have shown

motivation by asking for an opportunity to do more

exercises in Numbas, even when they have reached

the threshold. This can be seen from one teacher’s

response: “(...) I think the instant feedback is

motivating for the students”. The other teacher

suggested that “for most of them, at least for the way

I do it with this kind of programs they need (…) to

pass a certain amount of test to be able to attend

exam, ... and most of them will do it again even though

they have passed the test, because they want to

improve...I have got students that write to me asking

can you open the test again, I want to get 100%”.

Thirdly, in terms of quality feedback, one of the

students responded: “…with the two equations, there

was a movie, and it was sort of helping because it

assured me that I was doing it in the right way. The

third one, it was helping because it was the rule you

were supposed to use”. Another student explained

that “… it gives you a lot better feedback, than most

of that kind of programs …So that feedback is good,

and as I said, when you write, the next box shows you

how the program interprets, that program is really

good”. Students seem to appreciate the feedbacks,

including the video hints. The response from one

student does not only show that the video helped her,

but it also encouraged and motivated her to solve the

task. As a result, her confidence increased. Another

student tried to compare the feedback to that of other

similar tools and she found it better than other

programs she had used. She was particularly

overwhelmed that Numbas could instantly show how

it understands her answers.

Finally, in terms of instant or immediate

feedbacks, hints, and reveal answers, findings show

that the students equally found Numbas feedbacks

helpful and motivating. Teachers state that their

students “do get stuck” and when they do, that “most

of them chose to show hints and the tips, (and) the

other feedback options from the program”. They also

think that the feedbacks motivate the students.

Findings also reveal that engagement in Numbas

enhances students’ motivation. Students identified

among others, the instant feedback to be very

motivating. However, they believe that bulk of the job

lies on the teachers’ ability to create tasks that would

take into consideration students’ misconceptions

about a particular task.

They further expressed concerns that the

feedbacks, no matter how good it may be, may never

be sufficient to get some students going, especially

the low achieving students. This can be seen from one

of the teachers’ responses “I would say that the

feedback does help them but again for the strongest

students, it’s helpful for them but the weaker students,

I think they need the teacher actually to tell them what

they have done wrong, it’s not enough for them to see

the feedback or the examples.”

6 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this paper is to explore how Numbas

promotes formative assessment for mathematics

teaching and learning by analyzing the affordances

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

422

and constraints that emerge from interactions

between teachers/students and Numbas.

The main essence of formative assessment

according to Weeden et al. (2002) is to identify

students’ current performance that will hopefully lead

to improvement in learning and teaching. Therefore,

formative feedback is vital to improving mathematics

education (Pereira et al., 2016).

Feedbacks from teachers to students regarding

their performances, challenges and difficulties are

aimed at encouraging and helping them to identify

their misunderstandings and misconceptions

regarding the topics, concepts, and ways to improve.

Many studies have linked feedback as one the most

powerful ways to increase students learning and

achievement (eg. Hattie & Clarke, 2018; Hattie &

Timperley, 2007). However, delivering it on time is

often challenging to the teachers.

This is the reason why formative feedback is done

while Numbas is on-going. It is to identify how far

teaching and learning goals have been achieved.

Teachers and their students mostly undertake this

kind of assessment to obtain vital information in form

of formative feedback that they will apply to modify

and improve the ongoing teaching and learning

activity (Black & Wiliam, 2010).

Figure 2 and 3 show that achieving the goal

(formative feedback delivery), which is needed to

improve teaching and learning of mathematics

subject depends on the perception and actualization

of the emerged affordances of Numbas by students or

teachers. If they fail to actualize the affordances, the

intended goal may not be achieved.

The object is the mathematical knowledge in the

form of formative feedback while the subject is the

student/teacher, and the mediating artefact is

Numbas. Then, the outcome of a dynamic interaction

(activity) between the subject (student/teacher), the

object (formative feedback), and the mediating

artefact (Numbas) is the affordance of Numbas. Thus,

the goal of students is to receive formative feedback

from Numbas. However, the desired goal (formative

feedback delivery) does not manifest straight away.

In fact, it manifests as an effect of the actualized

affordances of Numbas.

In an activity system, teachers and students are the

subjects, and the goal of the teachers in their

relationship with students is to give feedback to the

students or receive feedback about the students’

performance through Numbas. While the goal of

students is to receive feedback from teachers through

Numbas. Therefore, formative feedback delivery is

the common goal, but the ultimate goal, which is the

effect of the formative feedback delivery is to

improve teaching and learning of mathematics.

According to the theoretical framework, the desired

goal (formative feedback delivery) does not manifest

itself directly, but as an effect of actualization of

Numbas affordances. Moreover, the emergence of

Numbas affordances is viewed as an offshoot of a

dynamic relationship between students/teachers and

Numbas, and the perception of the emerged

affordances concerns its awareness by

students/teachers. Whereas actualization is the action

taken by the students/teachers to take advantage of

the perceived affordances.

When students and teachers actualize some

required affordances, then the effect will lead to

achieving the goal (formative feedback delivery) and

by extension improves teaching and learning. For

example, when a student wants to solve mathematical

problems at home using Numbas, her/his goal is to

achieve formative feedback through the mediation of

Numbas. However, she/he must first of all actualize

the affordance of accessibility (amongst other

affordances needed). If the student faces constraint of

internet connection, then the effect will be that she/he

will not achieve her/his goal (formative feedback

delivery) because she/he could not actualize an

important affordance required. But if the student

actualizes the affordance by accessing the internet,

she/he may achieve the goal (formative feedback

delivery), however this is subject to actualizing other

feedbacks (like ease of use, navigate, etc.) she/he

might also need to successfully achieve the goal.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The main contribution of this paper is the

development of a theoretical framework drawing on

a combination of AT and affordance theory. AT has

proved to be useful for arguing that the emergence of

Numbas affordances is a result of a dynamic

relationship between a goal-oriented user and the

assessment tool. Likewise, affordance theory has

shown to be a useful in explaining the distinctiveness

of the perception and actualisation processes of

affordances. However, the framework as presented in

this study is not intended to map all affordances and

constraints, but it is open enough to capture potential

affordances. This is the reason why the deductive-

inductive approach to data analysis is so important for

the emergence of affordances. Moreover, Csapó et. al.

(2012) posited that large-scale implementation of

computer-based assessment systems still needs

further investigations in real education settings.

Formative Feedback in Mathematics Teacher Education: An Activity and Affordance Theory Perspective

423

Summarizing, the findings show that Numbas is

basically a useful tool for assessing mathematical

concepts and problem-solving. However, there are

issues related to the feedback, which can act as a

source of motivation for a few students while

demotivating other students. Numbas may be

included in the Norwegian curriculum with the sole

intention of identifying possible problems and

effecting necessary modifications along with

improving the learning of students and teachers. For

teachers, it is important to ascertain their role in using

their skills and expertise for adding new tasks of

formative assessment, and identifying students’

learning progress, while for students, it is important

to focus on using Numbas as a practice, learning, and

feedback tool. However, the role of Numbas should

be clearly defined along with the role of teachers.

From a practical point of view, the study has two

limitations. Firstly, the participants (N=8) are

master’s students and their teachers (N=2) from a

teacher education program of one university. A larger

number of participants from several universities

could have been more desirable to make better

generalization. Nevertheless, the chosen number of

participants with a large set of information seems to

be justifiable for addressing the research questions.

The second limitation is that the participative

students are not the ‘end users’ of Numbas. Though

they have sufficient knowledge of Numbas, and used

the tool for assessment, but in a limited form.

However, it is difficult to generalize their views to

encompass students using Numbas regularly in their

studies. Students from other study programs using

Numbas for day-by-day activities may have a

different perspective about perception of affordances

and actualization processes. Future research studies

involving such set of students would be relevant to

compare with findings of the present study to achieve

more reliability and validity of the results.

REFERENCES

Anderson, C., & Robey, D. (2017). Affordance potency:

Explaining the actualization of technology affordances.

Information and Organization, 27(2), pp. 100-115.

Bernhard, E., Recker, J., & Burton-Jones, A. (2013)

Understanding the actualization of affordances: A study

in the process modeling context. In M. Chau, & R.

Baskerville (Eds.). Proceedings of ICIS 2013.

Association for Information Systems, pp. 1-11.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of

formative assessment. Educational Assessment,

Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), pp. 5-31.

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford, UK:

Oxford University Press.

Csapó, B. et al. (2012) Technological issues for computer-

based assessment. In: Griffin P., McGaw B., Care E.

(eds.). Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills.

Springer, Dordrecht.

Day, D., & Lloyd, M. M. (2007). Affordances of online

technologies: More than the properties of the technology.

Australian Educational Computing, 22(2), pp. 17-21.

Engeström, Y. (2014). Learning by expanding: an activity-

theoretical approach to developmental research.

London: Cambridge University Press.

Gibson, J. J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual

perception. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hadjerrouit, S. (2020). Exploring the affordances of SimReal

for learning mathematics in teacher education: A Socio-

cultural perspective. In L. H. Chad; S. Zvacek; & J.

Uhomoibhi (2020). Computer Supported Education.

11th International Conference, CSEDU 2019,

Heraklion, Greece. Revised Selected Papers. Springer

Nature, pp. 26-50.

Hadjerrouit, S., & Nnagbo, C. I. (2021). Exploring Numbas

Formative Feedback for Teaching and Learning

Mathematics: An Affordance Theory Perspective. In:

D.G. Sampson, D. Ifenthaler, D., & Isaías, P. (2021).

Proceedings of CELDA 2021. IADIS Press, pp. 261-268.

Hattie, J., & Clarke, S. (2018). Visible learning: Feedback:

London: Routledge.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback.

Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp. 81-112.

Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative

research methods. SAGE Publications Limited.

Lawson-Perfect, C. (2015). A demonstration of Numbas, an

e-assessment system for mathematical disciplines. CAA

Conference. Retrieved from https://www.numbas.

org.uk/blog/2015/07/a-demonstration-of-numbas-at-caa-

2015/

Leont’ev, A. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and

personality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Nnagbo, C. I. (2020). Assessment in mathematics education

using Numbas: Affordances and constraints from an

activity theory perspective. [Unpublished master’s

thesis]. University of Agder, Norway.

Norman, D. A. (1988). The psychology of everyday things.

New York: Basic Books.

Pereira, D., Flores, M. A., Simão, A. M. V., & Barros, A.

(2016). Effectiveness and relevance of feedback in

Higher Education: A study of undergraduate students.

Studies in Educational Evaluation, 49, pp. 7-14.

Volkoff, O., & Strong, D. M. (2017). Affordance theory and

how to use it in IS research. In R. D. Galliers & M.-K.

Stein (Eds.). The Routledge companion to management

information systems. London: Routledge.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of

higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Weeden, P., Winter, J., & Broadfoot, P. (2002). Assessment.

London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods,

4th ed., vol. 5. Applied Social Research Methods Series.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

424