Human Energy Diary Studies with Personalized Feedback:

A Proof of Concept with formr

Fabienne Lambusch

1a

, Henning Dirk Richter

1b

, Michael Fellmann

1c

, Oliver Weigelt

2d

and Ann-Kathrin Kiechle

3

1

Business Information Systems, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

2

Institute of Psychology, Wilhelm Wundt, Leipzig University, Leipzig, Germany

3

Work and Organizational Psychology, University of Hagen, Germany

Keywords: IT-based Intervention, Momentary Assessment, Personalized Feedback, Self-reflection, Energetic Wellbeing.

Abstract: While the current pandemic amplifies the trend of highly self-responsible and flexible work, many employees

still struggle addressing the resulting self-management challenges like balancing strain and recovery.

Maintaining health of employees is a major concern of organizations to remain competitive, but in the context

of highly individual work, this can hardly be supported with classical occupational health initiatives. Thus, it

is crucial to develop tools that provide individuals with personal insights on their everyday work and help

them determine applicable health behaviors. Towards this goal, we report on our design and implementation

of diary studies with personalized feedback about persons’ energetic wellbeing. Whereas such studies enable

to research phenomena at the collective level, they can additionally act as intervention at the individual level.

This is especially relevant to 1) provide a motivational incentive for continued participation and 2) raise

awareness about recent topics in occupational health and promote healthy behaviors, while advancing research

concerns. We provide insights from several studies regarding the generated feedback, the perception of the

participants and IT-related improvement potentials. Hopefully, this will inspire further research that takes

advantage of the win-win situation conducting studies, which simultaneously provide participants with

individual insights.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the past decades, working conditions shifted more

and more towards complex and knowledge-intense

tasks, increased expectations for flexibility, and high

speed (Green and McIntosh, 2001; Parent-Thirion et

al., 2017; Biletta et al., 2021). Thus, managing

balance in life became more challenging for

individuals (Green and McIntosh, 2001; Barber and

Jenkins, 2014). In this context, the so-called

human energy plays a major role. Quinn et al. (Quinn

et al., 2012) describe human energy as an

organizational resource that increases employees’

ability to act by motivating them to do their work and

achieve their goals. Human energy is an umbrella

term that comprises physical aspects, like the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0303-1430

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9051-4042

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0593-4956

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4328-3445

available glucose in the blood enabling humans to act,

and subjective aspects, like the degree of feeling

alive. Quinn et al. call these two components physical

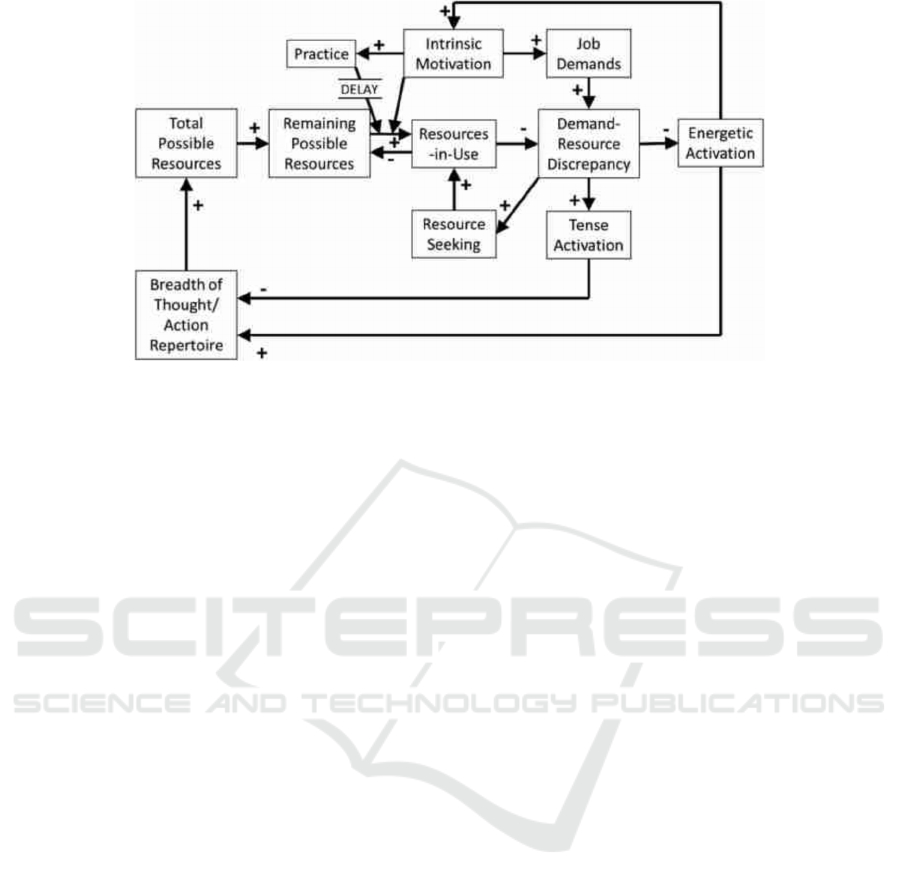

energy and energetic activation and present an

integrated model of human energy at work that can be

seen in Figure 1. Yet, research provides only scattered

indications of which factors influence especially the

subjective component of energetic activation and how

an employee can proactively improve energy

management on an individual level (i.e. energy self-

management). Although prior research investigated

the fields of job design (Grant and Parker, 2009),

leaderships (Inceoglu et al., 2018; Skakon et al.,

2010) and interventions (Tetrick and Winslow, 2015)

in order to foster employee wellbeing, addressing

self-management challenges via digital solutions has

Lambusch, F., Richter, H., Fellmann, M., Weigelt, O. and Kiechle, A.

Human Energy Diary Studies with Personalized Feedback: A Proof of Concept with formr.

DOI: 10.5220/0010974100003123

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2022) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 789-800

ISBN: 978-989-758-552-4; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

789

Figure 1: The integrated model of human energy over time in a work context (Quinn et al., 2012), which is a theoretical basis

of the presented studies with feedback on human energy.

not yet received much attention (Li and Vogel, 2021).

Self-management is key to find and improve the own

individual way to perform (Drucker, 2005). It means

controlling the own actions in a way that prefers

behaviors with consequences desirable in the longer-

term over short-term outcomes (Manz and Sims,

1980). Self-management skills are essential for work

characterized by high degrees of freedom (Kleinmann

and König, 2018). In order to manage oneself, several

strategies can be used. Self-observation, where a

person systematically gathers data about the own

behaviour (Manz and Sims, 1980), is an exemplary

strategy that is especially relevant in our context.

Indeed, designing and implementing IT-based tools

that support employees in the collection and analysis

of data relevant for self-reflection is a promising

avenue of research (Choe et al., 2017; Rapp and Cena,

2014; Fallon et al., 2018). Specifically for human

energy, there is yet no technical support assisting

individuals in identifying how different factors like

micro-breaks (Kim et al., 2018) influence their energy

level. Determining the influencing factors that are

particularly relevant within the own working day

would be highly valuable in order to proactively

increase the own energy level or prevent a decrease.

Diary studies help to regularly gather data about

peoples’ situation, especially if there is no established

automatic measurement instrument like sensors for

the targeted phenomena yet. They provide gaining

insights over a certain period of time by requiring the

participants to submit protocols of their activities

independently and frequently (Janssens et al., 2018).

The character of a diary study enables combining

research with the provision of early and individual

feedback to the participants of the studies, even

before the detailed scientific analyses take place that

focus more on generalizable results. Overall, diary

studies are very reasonable to keep track of dynamics

in experiences of and between employees in

organizations (Ohly et al., 2010). As diary studies can

require much time from the participants depending on

how frequently and deeply they are asked to assess

their situation, providing individual feedback may

raise the intrinsic motivation for regular participation

(Vries et al., 2021). With this, the participants expect

and receive insights, they are likely interested in.

Through generating personalized feedback on human

energy during work days, we furthermore strive to

empower employees to better understand their energy

and improve their management in such a way that

enables overload prevention and lasting work

pleasure. This would create added value for the

individual as well as the organization, which in

addition might lead to a better feasibility of

implementing diary studies for research purposes in

organizational contexts.

However, the design and implementation of IT-

supported diary studies with personalized feedback

remain challenging in terms of the technical

infrastructure required and the existing sample cases

described in sufficient detail to learn from. In

addition, there is also a lack of research how

participants perceive personalized feedback in diary

studies. Against this gap, we report on the design,

implementation and execution of our IT-supported

diary studies on human energy using the established

tool formr. Our results thus can inform the design and

implementation of future IT-supported diary studies

that emphasize personalized feedback.

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

790

2 RELATED WORK

In this section, we provide information on related

studies and tools starting with ambulatory assessment

studies more generally and proceeding with

electronic diary studies with feedback and the digital

tool we used for our diary studies.

2.1 Ecological Momentary Assessment

and Intervention Studies

A term commonly used in diary research is ecological

momentary assessment (EMA), which includes

diverse ambulatory assessment methods (Janssens et

al., 2018). EMA refers to methods involving repeated

sampling of subjects' current behaviors and

experiences in real time (= “momentary”) in the

natural environment (= “ecological”). Thus, EMA

comprises not only methods using diaries, but also

such using e.g. physiological sensors (Shiffman et al.,

2008).

Existing electronic EMA studies are often

focused towards researching interesting phenomena

such as (clinical) symptoms, behaviors or perceptions

and their interplay. For example, there are numerous

studies that focus on understanding basic

psychological need fulfillment at the workplace, as

summarized by Coxen et al. (2021) in their analysis

on 20 diary studies. Giving participants feedback is

not at the heart of such studies. Rather, data is

collected for understanding and gaining scientific

knowledge about the phenomenon under

consideration. Vries et al. (2021) focus in their review

on smartphone-based EMA studies on wellbeing and

explicitly recommend providing feedback to the

subjects at the end of the study in order to motivate

them for continued participation. Even though about

half of the analyzed 53 smartphone-based EMA

studies additionally integrate passive sensor data,

nearly all studies also use the collected data for their

research analyses only. The review mentions just one

exemplary study, in which participants got feedback

in form of personalized graphs about their happiness.

We will look at this study in the next section, as its

approach is quite similar to what we propose.

In addition to the more insight-oriented studies

described so far, there are also intervention-oriented

studies. In the mobile context, such studies aim at

delivering just-in-time prompts as treatments, as

indicated in a review on 27 ecological momentary

intervention (EMI) studies with mobile technology

support (Heron and Smyth, 2010). This sort of

feedback often is directive in its nature and presented

e.g. in the form of small textual messages.

Alternatively, interventions are offered by questions,

conversational interaction, or multimedia content as

described in a review study on 64 EMI studies by

Balaskas et al. (2021). Four of the analyzed studies

actually provided participants feedback in form of

graphical data visualizations of past entries. These

studies are addressed in the next section together with

others including visual feedback. However, the

feedback provided seems to be a bye-product of the

actual goal to deliver and research momentary

interventions that are used as treatments and is often

just roughly mentioned. In contrast to EMI designs,

we propose to utilize the integration of rich

visualizations of participant data for reflective

purposes and higher participation motivation even for

studies that have mainly an assessment character and

do not necessarily aim at intervening in opportune

moments.

To summarize, while previous work mostly

focused on insight-oriented or intervention-oriented

studies, we specifically focus on a study type between

these that enables assessments for research purposes,

but includes a reflective benefit for the participants

providing rich and personalized feedback. Besides the

benefit for participants, this approach also provides

the perfect basis to evolve an insight-oriented study

later into an intervention-oriented study using the

feedback as an intervention for reflection or adding

other interventions. This would also promote the

connection of EMA and EMI techniques that

remained largely separate, but would enable better

tailoring and delivery of interventions (Heron and

Smyth, 2010). In the next section, we analyse the few

works that are closer to our approach by providing

reflective visual feedback on the collected data.

2.2 Electronic Diary Studies with

Feedback Generation

According to Narciss (Narciss, 2006), feedback is an

information given to a person during or after a process

in order to have a regulating effect on that process.

Zannella et al. (Zannella et al., 2020) state a beneficial

effect caused by feedback, if used cautiously. They

argue that providing participants with personalized

feedback may not be generally feasible, especially

where results can be sensitive or easily misinterpreted

as a wrong psychological diagnosis. Thus, they

suggest carefully deciding which captured data is

considered for feedback and how it is presented to

decrease the risk of misconstruing.

Unfortunately, many research documentations

about diary studies with feedback generation neither

describe the design nor the impact of the generated

Human Energy Diary Studies with Personalized Feedback: A Proof of Concept with formr

791

feedback. The authors then just mention that feedback

was provided for the participants, but do not explain

more on that (Rentzsch et al., 2021; Richter and

Hunecke, 2021; Arslan et al., 2019a; Arslan et al.,

2019b; Holzleitner et al., 2017; Pusch et al., 2020;

Depp et al., 2015; Kazemi et al., 2019).

Few works at least shortly describe the feedback

they generated for their participants. For example,

Burns et al. (2011) provided participants visual

feedback related to depression, e.g. a graph showing

the frequency of the locations they were at together

with their average reported mood in each location.

Kroska et al. (2020) developed an application for

assessment and intervention in their study that can

visualize data collected regarding mood and activity.

Participants can access graphs e.g. on their depressive

symptoms, perceived stress symptoms, or certain

behavior over three days. Advanced visual feedback

on health and wellbeing was provided to participants

in the study by van der Krieke et al. (2017). Besides

some rather basic graphs like frequency of certain

activities ranked by perceived pleasantness, also

personal networks showing concurrent and dynamic

relationships between mood, health behaviors, and

emotions over time were presented to participants.

While the aforementioned studies can well inspire the

design of feedback to be generated for the

participants, they all lack describing their technical

infrastructure and corresponding study design in

sufficient detail for reuse. Researchers conducting

EMA studies often use applications, which were

specifically developed for their research and thus the

development costs a lot of time and money (Vries et

al., 2021). For studies with feedback generation, it is

even more important to build on an existing

infrastructure to reduce complexity of

implementation. Non-commercial tools that provide

functionality for conducting a diary study as well as

generating comprehensive personalized feedback

while fulfilling research demands (e.g.,

reproducibility, traceability, privacy guaranteed or

extensibility), are still rarely found. Furthermore,

non-commercial software is often poorly maintained

due to limited resources (Arslan et al., 2019c).

Arslan et al. (2019c) developed a study

framework and an open-source software tool that

tackles this gap, namely formr (see next section for

more information). They describe in their paper three

case studies with automatized feedback illustrating

the capabilities of their tool. One exemplary diary

study with personalized feedback aimed to

investigate daily habits and sexuality of women over

a period of 70 days. The participants received various

personalized feedback at the end of this study. In

addition to personality feedback, the study provided

them with visualizations of the variation of their

mood, desire and stress level during their menstrual

cycle. The participants could even investigate several

visualized correlations between the quality of their

sleep and mood level and their alcohol consumption

on the previous day. Additionally, an interactive

display provided the participants the possibility to

retrace their mood level over time and investigate

their answers from a specific day. Moreover, the

participants were also provided with a spider diagram

showing the distribution of activities in portions

during the week and the weekend.

Conducting a study with formr that uses diverse

of its features, is still challenging due to the

complexity of possibilities and the still rather short

information on exemplary cases. With this article, we

contribute an exemplary case with descriptions of

study designs, implementation choices, participant

perceptions, technical challenges, and learnings from

our study on human energy, specifically focusing on

combining EMA and personalized feedback. We

provide with this a proof of concept for future studies

and hope to reduce barriers other researchers may

face when conducting a similar study.

2.3 formr – A Tool for Diary Studies

Arslan et al. (2019c) developed formr, a study

framework and an open-source software tool

supporting researchers in conducting a wide range of

studies (i.e., from simple surveys to even more

intricate research). Thereby, it allows to

automatically send email or SMS notifications to

registered participants. Researchers can thus

determine a specific time schedule formr follows. The

notifications embody an external trigger to remind

and motivate participants to do their self-assessments.

Furthermore, formr supports the coding language R

to execute more complex tasks like generating

personalized feedback. Through coding in R, a wide

range of different visualizations can be created for the

feedback. For instance, a participant’s data can be

shown in a table, pie chart, bar chart, line graph or

radar chart.

Overall, the formr framework consists of three main

elements: 1) the survey framework, 2) the study

framework (aka “run”) and 3) the R package. In the

survey, researchers can define questions and to

correspondingly gather data from participants. The

“run” of provides researchers the possibility to

actively manage and drive the survey (i.e.,

researchers can manage access to a study, define

when which questions are answered by whom, send

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

792

emails or text messages to remind or invite the

participants and provide feedback to the users).

Whereas those two main components of formr are

coded in PHP, the third one is the utility R package

und thus independent from the other PHP code. This

should ensure common operations (like cleaning and

aggregating data or setting timeouts for analyzing

purposes) becoming easier to implement for the

researchers. The R package is connected to the PHP

software via a RESTful API allowing researchers to

use many familiar packages directly in formr (e.g., for

displaying graphical feedback to the users. Overall,

those features seem to perfectly fit the requirements

of performing longitudinal studies and thus also diary

studies. That is, data can be gathered from

participants by creating surveys, the execution of

those surveys can be maintained in the runs (e.g., by

reminding inactive users to continue participating)

and the gathered data can be precisely analyzed

afterwards using the R packages.

3 STUDY DESIGNS

Based on positive response of participants in first

studies, we conducted three diary studies on human

energy over the last three years where we combined

researching human energy in terms of energetic

activation and its influencing factors with developing

a flexible study procedure and valuable feedback for

the participants of the studies. In this, we iteratively

improved the personalized feedback provided to the

participants and added more and more complexity to

it in order to maximize knowledge gain. All studies

had a similar procedure design, but with different

frequencies of requested self-assessments per day and

different influencing factors and corresponding

scales. While our procedure design could function as

a blueprint for future studies, the things we changed

from study to study are the key elements to adjust for

each new context, in which a diary study based on our

design shall be conducted. The key concept and

influencing factors depend on the objective of the

research and on the demands of the studied domain or

organization. Furthermore, an essential lesson learnt

from conducting our studies is that feedback on

influencing factors is relevant mainly, if the assessed

factors are actionable in terms of a possibility for the

participants to change the manifestation of the factor.

Thus, we shifted the items assessed in the last study

more to behavioral strategies. From a research point

of view, the frequencies of assessments should be as

high as possible to collect a large data set for

subsequent analyses. However, in practice the

frequencies of self-assessments and number of items

used for assessment strongly rely on the feasibility in

terms of the time needed by the participants to answer

the surveys. This is especially true in case of

assessments during the work day as in our study

designs. In the following, the commonalities of the

study designs are described first and then illustrated

by the exemplary procedure of our latest study. Each

design consisted of:

• An initial questionnaire for contact and

demographic data

• Individual survey days including only work

days

• A number of surveys per day with a designated

e-mail reminder

• A short energy-related measurement at each

measurement point for the momentary state

• Scales for retrospective assessments of different

influencing factors, e.g. sleep quality, work

characteristics, recovery activities, and used

work strategies

• Feedback generated from the individual data

Two of our three studies included ten survey days

with up to four surveys per day at meaningful time

points for work and leisure – in the morning, noon,

afternoon, and evening. In one study considering an

average working day with eight hours, there were

even up to eight surveys a day to complete, but just

for three days of participation then and with the same

questionnaire for all diaries. In the last studies, a final

questionnaire asked for the participants’ perception of

the study and generated feedback. The rest of this

section describes the so-called formr run (cf.

Section 2.3) of our latest study in order to illustrate

with a concrete example, how the procedure of further

studies can look like. The procedure is as follows:

When entering the study link, the questionnaire

shown first is for meta data like the email address for

further invitations, the favored starting day, typical

start time of the working day, and some demographic

data. Furthermore, the participants are asked to

estimate how their energy might develop throughout

a typical day. For this, we used a pictorial scale of

human energy (Lambusch et al., 2020; Weigelt et al.,

2022) as shown in Figure 2, because it is more natural

estimating a status with just one visual item.

The main study starts with an invitation link to the

first diary entry after a waiting time that lasts until the

chosen starting day one hour after the participant’s

individual work begin. Every diary contained a short

energy-related measurement comprising the pictorial

scale of human energy and a few items of verbal

scales.

Human Energy Diary Studies with Personalized Feedback: A Proof of Concept with formr

793

Figure 2: Pictorial scale of human energy with seven

response options ranging from a depleted to a fully-charged

battery according to Weigelt et al., 2022.

As energetic activation represents the subjective

experience of human energy, it includes all facets of

experiencing the presence or absence of energy, e.g.

vitality or zest, fatigue or exhaustion. With the

diversity of focal aspects of the phenomenon, there

are many common instruments that can be used to

measure sub-concepts of human energy in terms of

energetic activation. In order to keep the diaries as

short as possible, we had to decide for few focal

aspects to measure. We chose to use three items of the

vigor-subscale of POMS (Albani et al., 2005). In

earlier studies we used Ryan and Frederick’s

subjective vitality scale as adapted by Schmitt et al.

(Schmitt et al., 2017). Furthermore, we used three

items of the tension-subscale of POMS (Wyrwich and

Yu, 2011) for every diary in this study. The morning

diary, to which the mentioned invitation link leads,

complements the energy measurement with questions

about sleep, including e.g. the Insomnia Severity

Index (Bastien, 2001) and the day so far, e.g. morning

reattachment (Sonnentag and Kühnel, 2016), and

items for planning and goal setting of the German

version of the revised self-leadership questionnaire

(Andreßen and Konradt, 2007). The run waits 90

minutes for the participant to click the invitation link

and complete this diary entry and skips it in case the

participant doesn’t click the link. In any case the next

module is to wait until the individually chosen lunch

time, where the next invitation email with a link to the

noon diary is sent. In the noon diary questions about

e.g. job crafting (Lopper et al., 2020) complement the

energy measurement. As this entry shall be completed

after lunch and the invitation is sent at the given lunch

time, we wait a bit longer here for the participant to

complete the diary entry, namely 120 minutes, before

this diary is skipped. The afternoon diary is always

sent at 4 pm with a waiting time of 90 minutes and the

evening diary at 7 pm with a waiting time until 11:59

pm before the entry is skipped. In the afternoon

questions are posed about e.g. autonomy (Stegmann

et al., 2010), elective selection (Schmitt et al., 2012)

and micro-breaks (Kim et al., 2018). while in the

evening we ask for concepts like work-life-balance

(Syrek et al., 2011) and progress through

supplemental work (Weigelt and Syrek, 2017).

The described daily procedure starting with a

morning diary and ending with an evening diary is a

loop repeated over the course of the study. However,

invitations for diary entries are only sent on

workdays, not on weekends. Thus, on weekends a

waiting time takes effect. After five days of diary

entries, the participants of the second group get their

intermediate feedback after completing or skipping

the evening entry. After ten days of diary entries, all

participants get final feedback. After a pause, an

invitation to a closing survey is sent to the participants

to ask for perception of the study and generated

feedback. After completing this survey, the

participants have again access to their final feedback

via the link. Explanations and exemplary excerpts of

the generated feedback are given in the next section

on feedback development.

4 DEVELOPMENT OF

PERSONALIZED HUMAN

ENERGY FEEDBACK

The feedback generated in our studies is intended to

empower employees to better understand their energy

levels and improve their energy self-management. In

this way, we strive to enable overload prevention and

promote lasting work pleasure. Instead of providing

just general information and tips, the feedback is

created personalized from the individual data, e.g.

showing a selection of only those influencing factors

most relevant for the specific person. The diary study

feedback can be seen as a step towards a

comprehensive tool helping people to identify those

factors, which have a major influence on their

individual energy level. To date, our study results

already indicate how highly individual energy curves

and factors are, supporting our endeavor and the

necessity for individual feedback complementing

rather general recommendations on energy self-

management.

When designing the feedback, we decided that the

it should at least include graphs visualizing the

development of the participant’s energy and

representations of how the different scales correlate

with it. In our latest feedback design, we additionally

provide information on the development of the

person’s tension as well as on the manifestations of

the assessed influencing factors in the everyday work

life of the participant. Researchers should carefully

elaborate how to visualize which data in advance to a

run. For instance, visualizing a user’s level of human

energy over the time of a day in a line graph seems

more suitable than showing its portions in a radar

chart. Oppositely, visualizing the manifestations of a

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

794

user’s different working characteristics in

comparison seems to be more reasonable with a radar

chart than with a line graph (cf. e.g. Chapter 6.3 in

(Skiena, 2017) on chart types). As it is very important

to enable the participants to understand what the

feedback means, descriptive texts should explain the

feedback data and limitations in interpretation. The

generated feedback actually addresses critical data in

the sense of Zannella et al. (Zannella et al., 2020).

Thus, its presentation was carefully elaborated in

collaboration with psychologists and cautionary notes

were included, e.g. for the influencing factors

regarding the difference between correlations and

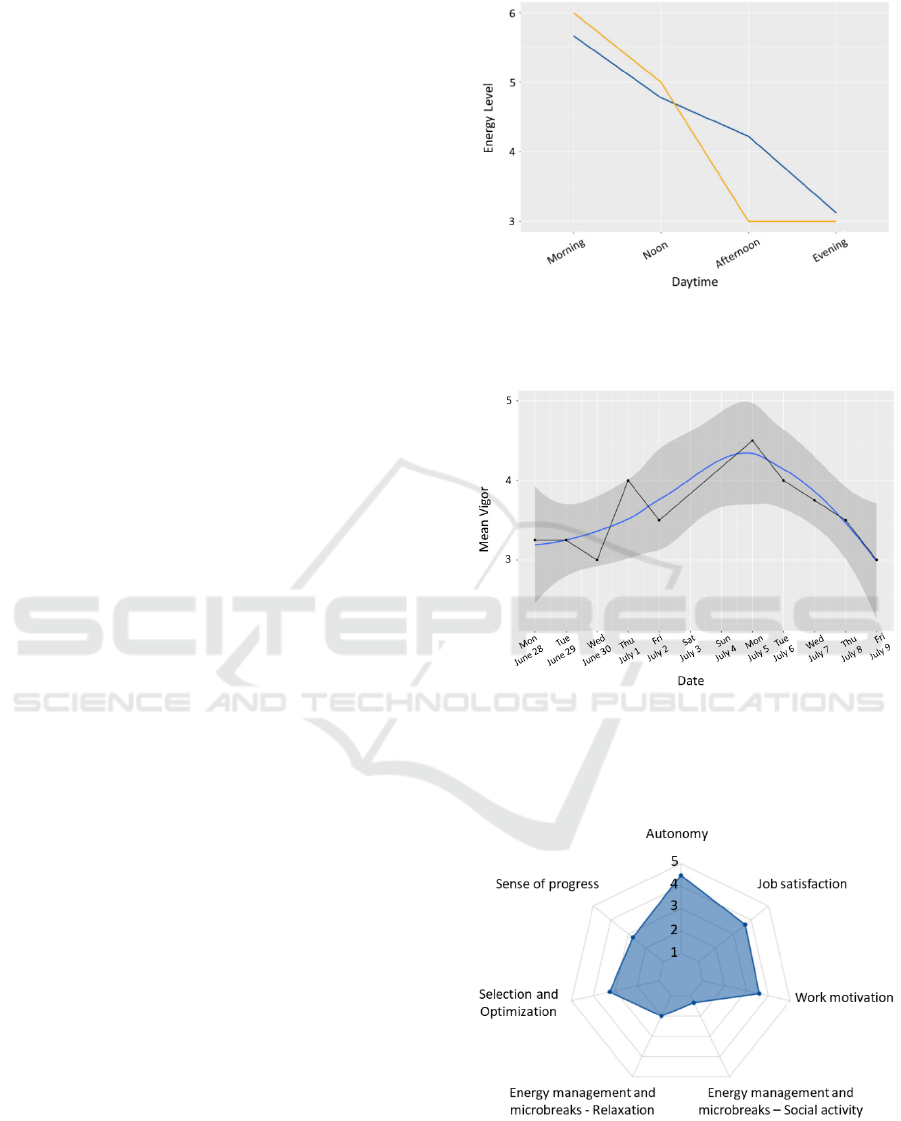

causality. In order to visualize the development of the

participant’s energy level, two time contexts are

important according to existing research: 1) the day

level (Golder and Macy, 2011) and 2) the week level

(Weigelt et al., 2021). Thus, we provide the

participants with a diagram for both levels. For the

day level the participants were requested to estimate

their mean energy throughout a typical work day with

the pictorial scale. In the feedback, we show them

their estimation together with their actual mean

energy curve over a day (cf. Figure 3). For the week

level, we provide the participants a graph with their

mean vigor (as one of the manifestations of human

energy) of each day during the whole study period (cf.

Figure 4). The figures shown in this section are the

graphs generated by formr, only texts in the figures

are changed in sizes and have been translated from

German. A similar curve as in Figure 4 is shown for

the participant’s tension over the diary study period.

Furthermore, we provide information on the daytime

with the minimum and maximum mean values for

energy and tension, e.g. maximum tension was in the

morning with a mean value of 2,2. Next, a series of

radar charts illustrates how strongly the possible

influencing factors assessed are pronounced in the

participant’s everyday working life (see Figure 5).

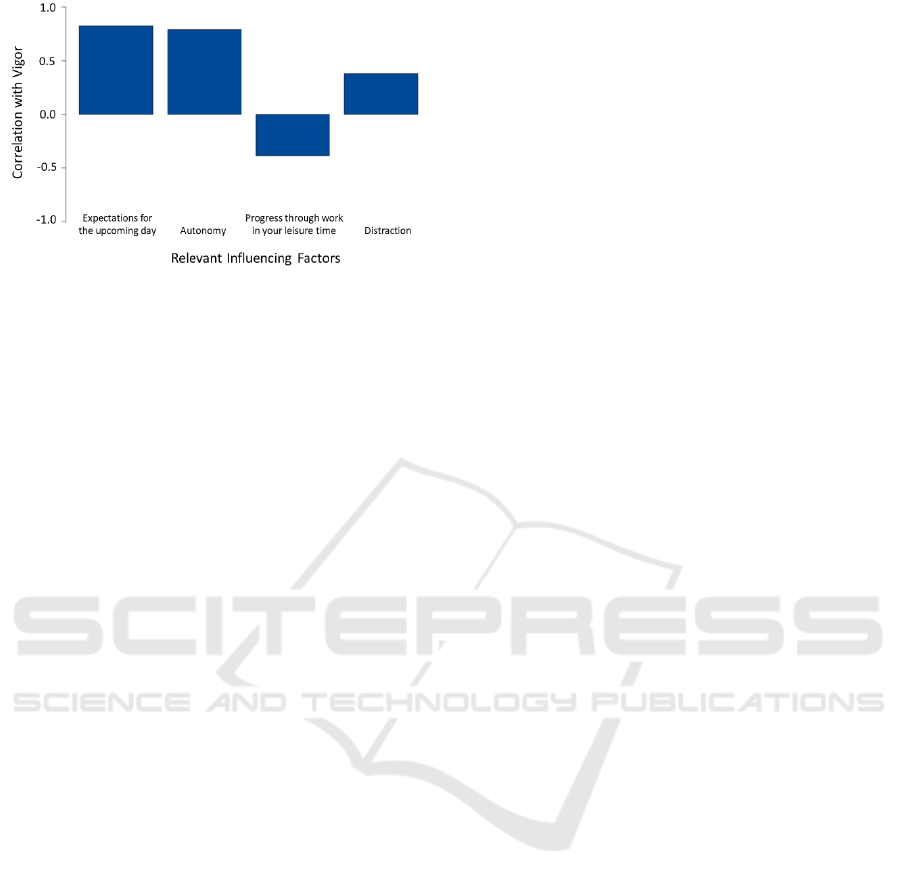

The last diagram of the provided feedback

represents a core element for energy self-

management, namely the four strongest correlations

of the influencing factors with the participant’s vigor

(cf. Figure 6). In case the participants are interested in

reviewing the course of the four strongest correlating

factors over the study period in comparison to their

energy, it would be possible to create for future

studies a graph similar to Figure 4, complementing it

with four other line graphs for the correlating factors.

Figure 3: Exemplary formr feedback diagram of a

participant’s estimated (orange) and actual (blue) mean

energy (1 to 7) over the course of a day.

Figure 4: Exemplary formr feedback diagram of individual

vigor (1 to 5) over the course of the study. The black graph

shows the connected measurement values, whereas the blue

graph represents a smoothed curve with an enclosing grey

area highlighting the general trend.

Figure 5: Exemplary formr radar chart for characteristics of

a participant’s typical day assessed in the noon. It shows the

mean assessment value for the factors across all days of

participation.

Human Energy Diary Studies with Personalized Feedback: A Proof of Concept with formr

795

Figure 6: Exemplary formr bar chart displaying the four

strongest correlation coefficients of the personal vigor to

possible influencing factors.

5 INSIGHTS FROM PROOF OF

CONCEPT STUDIES

We conducted a series of diary studies that

implemented the analyses and feedback we described

on a conceptual level in the previous chapter.

Participants were recruited using a convenience

sampling strategy, i.e. the invitation was spread

through word-of-mouth recommendation and social

media (e.g. posted on the platform Xing in a forum

about self-management and self-coaching). In sum,

74 persons participated in the studies. In the

following, we report on our insights during the studies

regarding feedback generation, participants’

perceptions and IT-support.

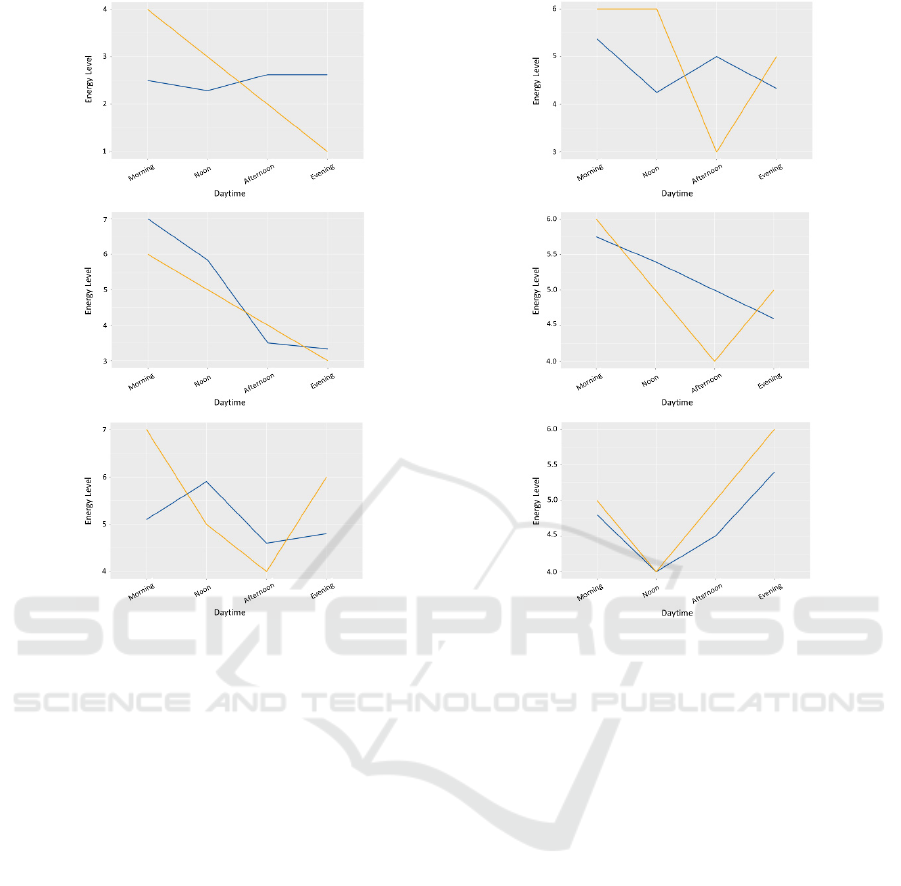

5.1 Observations from Data Analysis

Our study results show how much energy curves and

high correlating factors differ on an individual level,

which supports the need for personalized feedback in

addition to more general recommendations for energy

self-management. We illustrate the differences of

participants in daily energy in Figure 7. Also for the

high correlating factors, we observed that these are

largely different between subjects. An explanation for

this could be that participants differ in terms of e.g.

personality, cognition and also their working

conditions. An example for the latter is that postpone

or delegation behaviors are not possible if work-

related autonomy is rather small.

Furthermore, we were able to derive interesting

insights by analyzing the collected data. Since the

studies varied slightly and due to space limitations,

we are not able to report on all of our findings. A

sample finding is e.g. that negative correlations were

found for time spent in meetings and subjective

vitality. In regard to the factors influencing human

energy, it was e.g. discovered that strength use is

positively correlated with vitality. From this it can be

deduced tasks should be favored where personal

strengths can be applied and that time spent in

meetings should be reduced.

5.2 Preliminary Insights on How the

Participants Perceived the Study

In the studies we conducted, we collected both

qualitative and quantitative feedback from our

participants which we summarize below.

Comments to the applied scales. In general, we

did not receive negative feedback regarding the

understandability (with rare exceptions). However,

some new items were suggested by the participants

such as work tasks that were assigned at short notice

in the evening through mail, SMS or even phone calls

and that cause sleep problems or doing sports. A point

of criticism was that inapplicable questions could not

be omitted.

Feedback to the study execution. Concerning the

general study, there were only criticisms about the

procedure of the study. According to this, the study

should provide more flexibility, i.e. participants

wished to determine the time of the questionnaires

being sent and to limit questions to a subset they find

applicable for their daily life. Also, integration with

task calendar, e.g. in Outlook, was suggested in order

to not to miss questionnaires. Another idea was to

send funny and therefore encouraging messages to the

participants during the study in order to avoid the

“stiff” character of the questionnaires over time.

Furthermore, the issue of time-lag effects was raised,

e.g. to measure whether or not there is a drop in

performance after overproductive days.

General comments on the impact on personal life.

For many of the participants, these questionnaires

seemed to have a positive impact on their thoughts. In

some cases, it was reported that it stimulated

reflection and helped to gain insights into everyday

work and how different aspects affect work. In this

sense, the studies were able to provide “food for

thought”. Of course, some more critical remarks

occurred too. Predominantly, these were about

questions that were felt to be repetitive or irrelevant.

Also, the “one-off” nature of the feedback was

criticized, i.e. a more incremental feedback was

preferred.

Perceived relevance and usefulness of the

feedback. We included a final questionnaire at the end

of the last two studies to ask for participants’

perceptions of the feedback. In one of the studies,

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

796

Figure 7: Comparison of energy curves of different participants on the day level. Orange lines represent the participants’

estimated energy curve and blue lines the actual energy.

participants (n=27) had to specify their agreement on

a 5 point Likert scale ranging from disagreement (1)

to complete agreement (5). In regard to the

proposition that the feedback is useful for everyday

work, most of the participants answered with 3-4 with

approx. 42% for each value. In regard the assertion

that the time invested in the study is useful, approx.

68% of the participants highly or even completely

agreed to this (4-5). Moreover, more than 60% of the

participants answered with 3-5 regarding the question

of being able to integrate the content of the feedback

into their everyday work. Furthermore, being able to

derive personal benefit from the feedback of the study

was highly agreed (4) by approx. 37%. In regard

whether the participant’s knowledge could be

expanded in the long term with the help of the

feedback, this question was mostly answered with 2

(21.1%) and 3 (52.6%). Finally, in regard to the

statements that new knowledge could be generated by

the study and that something could be learned

through the study, most participants somewhat or

highly agreed (3-4). This is also consistent with the

overall average, as the most common response

options for the entire final questionnaire were 3 with

33.1% and 4 with 32.3%. In sum, over 60% of the

participants responded positively to the study

evaluation form.

5.3 Challenges and Learnings

regarding the IT-support

Regarding the technical implementation of the study,

the most important learning was that timing problems

should be handled with caution. There is a so-called

“expiry date”, which can be set in the settings of each

questionnaire. It determines how long a questionnaire

can be filled in. However, only when this period is

exceeded, the participant can receive the invitation

for the next questionnaire. The period between the

questionnaire in the morning and at noon, for

example, was set to 300 minutes first. However, this

did not take into account that often questionnaires do

not arrive on time at 7 a.m., but also sometimes later.

If this is the case, the “expiry date” overlaps with the

invitation time of the following questionnaire and an

error occurs where participants get stuck in the run

and do not receive any further invitations. The

problem could be solved by subtracting 10 minutes

Human Energy Diary Studies with Personalized Feedback: A Proof of Concept with formr

797

from the expiry date. Such timing problems may be

caused due to the computational load of the server

that is hosting the study. We currently explore this

issue further. Another logical error found was that

after entering the last questionnaire of a day, the

participants jumped via the rewind module to the

invitation on the next morning. However, this only

works if the respondent completes the questionnaire

on the same day. If this does not happen, the run skips

a day. This problem was also solved by implementing

an if-statement before the last questionnaire.

6 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Today’s working world can be characterized by

increased flexibility and ever growing complexity of

products and services in highly dynamic markets.

This induces high workloads, constant time-pressure

as well as blurring borderlines between different life-

domains. For individuals as well as organizations, it

can be hard to keep pace. Hence, good self-

management capabilities in terms of controlling the

own behaviors in a long-term desirable way are of

vital importance for promoting productivity as well as

sustainable health management. In this direction, we

suggest to combine researching phenomena with the

generation of personalized feedback as an integral

part of a study. In order to do so, we design and

implement IT-supported diary studies that provide

comprehensive and personalized feedback. In the

paper at hand, our contribution is that we (i) identify

and describe characteristics of such studies together

with the corresponding infrastructure (Section 3),

(ii) provide examples and suggestions for individual

feedback generation (Section 4) and finally (iii)

provide preliminary insights based on several studies

we already implemented and executed (Section 5).

A limitation of our research is the still small

amount of participants in our studies (n=74). In

addition, all of our studies were centered on working

behaviors and attitudes and their influence on

psychological constructs measured by established

scales, most notably “human energy”. Hence,

generalizations to other study topics have to be made

with caution so far. However, our results are quite

promising since in all studies, we were able to collect

required data, analyze the data and provide

meaningful feedback, according to our participants.

For the future, we want to develop our assessment

study with feedback further into a more intervention-

oriented study. In the first step, we will do this by

using the feedback as an intervention itself. Thus,

while we collected initial perceptions of the

participants on the generated feedback so far, we plan

to culminate the optimized conceptual and technical

realization focused in this article with a larger study

examining specifically the psychological effects of

our diary study with feedback on the participants. As

a next step, it could be decided, if further

interventions might be interesting to add and

research. Such interventions might be intended to

support behavior change. For example, if a person is

regularly low in energy after a meeting, the system

could suggest recovery strategies like taking a short

walk after meetings, so that this might become a habit

little by little.

Our approach may also be helpful in the domain

of eCoaching. Since coaching activities often imply

to explore and experiment with different

interventions and study their effect over a period of

time, the impact of different interventions could be

tested. Furthermore, an essential part of coaching

activities often is to identify contingencies between

variables, e.g. to identify how the interplay of certain

behaviors affects clinical symptoms or perceived

outcomes on target variables. Due to the powerful

statistical data analysis capabilities of R, such

contingencies could be identified in an automated

way and included in the personal feedback. Hence, an

avenue of future research would be to develop our

design more in the direction of coaching activities.

In summary, there is much opportunity for further

exciting developments and we hope that our results

will inform and inspire future IT-supported diary

studies that include personalized feedback as an

integral part of the study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank everyone who helped

implementing the different studies and feedback

designs, namely Maria Dehne, Christoph Gibcke,

Christoph Rosenau, Anastasiia Karpachova, Konrad

Seidler, Niklas Götz, Tabea Bröring, Leo Rehm,

Nikolas Rödel, Dennis Theuerkauf, and Miriam

Hacker.

REFERENCES

Albani, C., Blaser, G., Geyer, M., et al. (2005),

“Überprüfung der Gütekriterien der deutschen

Kurzform des Fragebogens ’Profile of Mood States’

(POMS) in einer repräsentativen

Bevölkerungsstichprobe, PPmP: Psychotherapie

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

798

Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie, Vol. 55

No. 7, pp. 324–330.

Andreßen, P. and Konradt, U. (2007), “Messung von

Selbstführung: Psychometrische Überprüfung der

deutschsprachigen Version des Revised Self-

Leadership Questionnaire”, Zeitschrift für

Personalpsychologie, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 117–128.

Arslan, R.C., Reitz, A.K., Driebe, J.C., et al. (2019a),

“Routinely randomise the display and order of items to

estimate and adjust for biases in subjective reports”.

Arslan, R.C., Reitz, A.K., Driebe, J.C., et al. (2019b),

Routinely Randomize Potential Sources of

Measurement Reactivity to Estimate and Adjust for

Biases in Subjective Reports, Center for Open Science.

Arslan, R.C., Walther, M.P. and Tata, C.S. (2019c), “formr:

A study framework allowing for automated feedback

generation and complex longitudinal experience-

sampling studies using R”, Behavior research methods.

Balaskas, A., Schueller, S.M., Cox, A.L. and Doherty, G.

(2021), “Ecological momentary interventions for

mental health: A scoping review”, PloS one, Vol. 16

No. 3, e0248152.

Barber, L.K. and Jenkins, J.S. (2014), “Creating

technological boundaries to protect bedtime: examining

work-home boundary management, psychological

detachment and sleep”, Stress and Health, Vol. 30

No. 3, pp. 259–264.

Bastien, C. (2001), “Validation of the Insomnia Severity

Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research”,

Sleep Medicine, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 297–307.

Biletta, I., Cabrita, J., Eiffe, F., Gerstenberger, B., Parent-

Thirion, A., Vargas, O. and Weber, T. (2021), Working

conditions and sustainable work. An analysis using the

job quality framework, Eurofound flagship report,

Dublin.

Burns, M.N., Begale, M., Duffecy, J., Gergle, D., Karr, C.J.,

Giangrande, E. and Mohr, D.C. (2011), “Harnessing

context sensing to develop a mobile intervention for

depression”, Journal of Medical Internet Research,

Vol. 13 No. 3, e55.

Choe, E.K., Lee, B., Zhu, H., Riche, N.H. and Baur, D.

(2017), “Understanding self-reflection. How People

Reflect on Personal Data Through Visual Data

Exploration”, in Proceedings of the 11th

PervasiveHealth, ACM, NY, USA, pp. 173–182.

Coxen, L., van der Vaart, L., van den Broeck, A. and

Rothmann, S. (2021), “Basic Psychological Needs in

the Work Context: A Systematic Literature Review of

Diary Studies”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 12, p.

698526.

Depp, C.A., Ceglowski, J., Wang, V.C., et al. (2015),

“Augmenting psychoeducation with a mobile

intervention for bipolar disorder: a randomized

controlled trial”, Journal of Affective Disorders,

Vol. 174, pp. 23–30.

Drucker, P.F. (2005), “Managing Oneself”, Harvard

business review.

Fallon, M., Spohrer, K. and Heinzl, A. (2018), “Wearable

Devices: A Physiological and Self-regulatory

Intervention for Increasing Attention in the Workplace”,

in Neurois retreat 2018, Lecture Notes in Information

Systems and Organisation, Vol. 29, Springer, pp. 229–

238.

Golder, S.A. and Macy, M.W. (2011), “Diurnal and

seasonal mood vary with work, sleep, and daylength

across diverse cultures”, Science, Vol. 333 No. 6051,

pp. 1878–1881.

Grant, A.M. and Parker, S.K. (2009), “7 Redesigning Work

Design Theories: The Rise of Relational and Proactive

Perspectives”, Academy of Management Annals, Vol. 3

No. 1, pp. 317–375.

Green, F. and McIntosh, S. (2001), “The intensification of

work in Europe”, Labour Economics, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp.

291–308.

Heron, K.E. and Smyth, J.M. (2010), “Ecological

momentary interventions: incorporating mobile

technology into psychosocial and health behaviour

treatments”, British Journal of Health Psychology,

Vol. 15 No. Pt 1, pp. 1–39.

Holzleitner, I.J., Driebe, J.C., Arslan, R.C., et al. (2017), No

evidence that inbreeding avoidance is up-regulated

during the ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle, Cold

Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Inceoglu, I., Thomas, G., Chu, C., et al. (2018), “Leadership

behavior and employee well-being: An integrated

review and a future research agenda”, The Leadership

Quarterly, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 179–202.

Janssens, K.A.M., Bos, E.H., Rosmalen, J.G.M., Wichers,

M.C. and Riese, H. (2018), “A qualitative approach to

guide choices for designing a diary study”, BMC

medical research methodology, Vol. 18 No. 1, p. 140.

Kazemi, D.M., Borsari, B., Levine, M.J., et al. (2019),

“Real-time demonstration of a mHealth app designed to

reduce college students hazardous drinking”,

Psychological services, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 255–259.

Kim, S., Park, Y. and Headrick, L. (2018), “Daily micro-

breaks and job performance: General work engagement

as a cross-level moderator”, The Journal of applied

psychology, Vol. 103 No. 7, pp. 772–786.

Kleinmann, M. and König, C.J. (2018), Selbst- und

Zeitmanagement, Praxis der Personalpsychologie,

Band 38, 1. Auflage, Hogrefe, Göttingen.

Kroska, E.B., Hoel, S., Victory, A., et al. (2020),

“Optimizing an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Microintervention Via a Mobile App With Two

Cohorts: Protocol for Micro-Randomized Trials”, JMIR

research protocols, Vol. 9 No. 9, e17086.

Lambusch, F., Weigelt, O., Fellmann, M. and Siestrup, K.

(2020), “Application of a Pictorial Scale of Human

Energy in Ecological Momentary Assessment

Research”, in Engineering Psychology and Cognitive

Ergonomics: Mental Workload, Human Physiology,

and Human Energy, Lecture Notes in Computer

Science, Vol. 12186, Springer Nature, pp. 171–189.

Li, J. and Vogel, D. (2021), “Digital Health Education for

Self-Management: A Systematic Literature Review”,

PACIS 2021 Proceedings.

Lopper, E., Horstmann, K.T. and Hoppe, A. (2020), “The

Approach-Avoidance Job Crafting Scale: Development

Human Energy Diary Studies with Personalized Feedback: A Proof of Concept with formr

799

and Validation of a New Measurement”, Academy of

Management Proceedings, Vol. 2020 No. 1, p. 18656.

Manz, C.C. and Sims, H.P. (1980), “Self-Management as a

Substitute for Leadership: A Social Learning Theory

Perspective”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 5

No. 3, pp. 361–367.

Narciss, S. (2006), Informatives tutorielles Feedback

Entwicklungs-und Evaluationsprinzipien auf der Basis

instruktionspsychologischer Erkenntnisse.

Ohly, S., Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C. and Zapf, D. (2010),

“Diary Studies in Organizational Research”, Journal of

Personnel Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 79–93.

Parent-Thirion, A., Biletta, I., Cabrita, J., et al. (2017), 6th

European Working Conditions Survey: Overview

report, EF, 16/34, 2017 update, Publications Office of

the European Union.

Pusch, S., Schönbrodt, F.D., Zygar–Hoffmann, C. and

Hagemeyer, B. (2020), “Truth and Wishful Thinking:

How Interindividual Differences in Communal Motives

Manifest in Momentary Partner Perceptions”, Eur J

Pers, Vol. 34 No. 1, pp. 115–134.

Quinn, R.W., Spreitzer, G.M. and Lam, C.F. (2012),

“Building a Sustainable Model of Human Energy in

Organizations: Exploring the Critical Role of

Resources”, Academy of Management Annals, Vol. 6

No. 1, pp. 337–396.

Rapp, A. and Cena, F. (2014), “Self-monitoring and

Technology: Challenges and Open Issues in Personal

Informatics”, in UAHCI 2014 and HCI, Vol. 8516,

Springer, Cham, pp. 613–622.

Rentzsch, K., Wieczorek, L.L. and Gerlach, T.M. (2021),

“Situation Perception Mediates the Link Between

Narcissism and Relationship Satisfaction: Evidence

From a Daily Diary Study in Romantic Couples”,

Social Psychological and Personality Science,

194855062098741.

Richter, N. and Hunecke, M. (2021), Are Mindful Days

More Sustainable? Mindfulness, Connectedness to

Nature, Personal Norm and Pro-environmental

Behavior in a Daily Diary Study, Center for Open

Science.

Schmitt, A., Belschak, F.D. and Den Hartog, D.N. (2017),

“Feeling vital after a good night’s sleep: The interplay

of energetic resources and self-efficacy for daily

proactivity”, Journal of occupational health

psychology, Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 443–454.

Schmitt, A., Zacher, H. and Frese, M. (2012), “The

buffering effect of selection, optimization, and

compensation strategy use on the relationship between

problem solving demands and occupational well-being:

a daily diary study”, Journal of occupational health

psychology, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 139–149.

Shiffman, S., Stone, A.A. and Hufford, M.R. (2008),

“Ecological momentary assessment”, Annual review of

clinical psychology, Vol. 4, pp. 1–32.

Skakon, J., Nielsen, K., Borg, V. et al. (2010), “Are leaders'

well-being, behaviours and style associated with the

affective well-being of their employees? A systematic

review of three decades of research”, Work & Stress,

Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 107–139.

Skiena, S.S. (2017), The data science design manual, Texts

in computer science, Springer, Cham, Switzerland.

Sonnentag, S. and Kühnel, J. (2016), “Coming back to work

in the morning: Psychological detachment and

reattachment as predictors of work engagement”, J.

Occup. Health Psychol., Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 379–390.

Stegmann, S., van Dick, R., Ullrich, J., et al. (2010), “Der

Work Design Questionnaire”, Zeitschrift für Arbeits-

und Organisationspsychologie A&O, Vol. 54 No. 1, pp.

1–28.

Syrek, C., Bauer-Emmel, C., Antoni, C. and Klusemann, J.

(2011), “Entwicklung und Validierung der Trierer

Kurzskala zur Messung von Work-Life Balance”,

Diagnostica, Vol. 57 No. 3, pp. 134–145.

Tetrick, L.E. and Winslow, C.J. (2015), “Workplace Stress

Management Interventions and Health Promotion”,

Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. Vol. 2 No. 1,

pp. 583–603.

van der Krieke, L., Blaauw, F.J., Emerencia, A.C., Schenk,

H.M., Slaets, J.P.J., Bos, E.H., Jonge, P. de and

Jeronimus, B.F. (2017), “Temporal Dynamics of Health

and Well-Being: A Crowdsourcing Approach to

Momentary Assessments and Automated Generation of

Personalized Feedback”, Psychosomatic Medicine,

Vol. 79 No. 2, pp. 213–223.

Vries, L.P. de, Baselmans, B.M.L. and Bartels, M. (2021),

“Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary

Assessment of Well-Being: A Systematic Review and

Recommendations for Future Studies”, Journal of

Happiness Studies, Vol. 22 No. 5, pp. 2361–2408.

Weigelt, O., Gierer, P., Prem, R., Fellmann, M., Lambusch,

F., Siestrup, K., Marcus, B., Franke, T., Tsantidis, S.,

Golla, M., Wyss, C. and Blume, J. (2022), Time to

Recharge Batteries – Development and Validation of a

Pictorial Scale of Human Energy, manuscipt submitted

for publication.

Weigelt, O., Siestrup, K. and Prem, R. (2021), “Continuity

in transition: Combining recovery and day‐of‐week

perspectives to understand changes in employee energy

across the 7‐day week”, Journal of Organizational

Behavior.

Weigelt, O. and Syrek, C.J. (2017), “Ovsiankina's Great

Relief: How Supplemental Work during the Weekend

May Contribute to Recovery in the Face of Unfinished

Tasks”, International Journal of Environmental

Research and Public Health, Vol. 14 No. 12, p. 1606.

Wyrwich, K.W. and Yu, H. (2011), “Validation of POMS

questionnaire in postmenopausal women”, Quality of

Life Research, Vol. 20 No. 7, pp. 1111–1121.

Zannella, L., Vahedi, Z. and Want, S. (2020), “What Do

Undergraduate Students Learn From Participating in

Psychological Research?”, Teaching of Psychology,

Vol. 47 No. 2, pp. 121–129.

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

800