Free Online Training and Value Perception in France

Gail Tidey

1

, Laurent Dedieu

1

, Annabel Levert

1

and Jean-Christophe Sakdavong

2

1

My Green Training Box, 3 rue de la Boucherie, Nailloux, France

2

CLLE CNRS UMR 5263, University of Toulouse, 5 allée Antonio Machado, Toulouse, France

Keywords: Free, Online Training, Value, Quality, Benefit.

Abstract: Digital training has taken on a major place in our society with the health crisis. Among the many online

training offers available, some are free of charge, so that the user does not have to pay for his or her learning,

and we can sometimes wonder about the value of these training courses: do they offer the same quality as the

paid ones? After collecting data from 245 people, our study shows that the price of an e-learning course does

not necessarily influence the value that the user attributes to it, and that a free course can have the same value

and interest as a paid course. Moreover, free training is a significant marker in the decision-making process:

it gives the training an additional benefit, which goes beyond the mere monetary savings made, compared to

the same paid offer. Therefore, free training can give the user the perception of a greater general benefit than

paid training.

1 INTRODUCTION

Associated with non-market and humanistic values,

the notion of free goods carries the seal of sharing,

and humanity has functioned for centuries without

systematically trying to put a price on objects and

services. However, the idea of the commons -

belonging to no one - has shrunk to a trickle since the

term market no longer refers to a gathering of a few

merchants in a village square on a Sunday morning...

A utopia, free access? For Heyman and Ariely

(2004), there is, alongside the money market, a

"social market" in which gift, friendship, social ties

exist. Nevertheless, when the two markets - monetary

and social - coexist, inevitably the former tends to

take over the latter (Heyman and Ariely, 2004). As

soon as money intervenes, the value of the donation

is immediately degraded and what remains of free

becomes suspicious.

This explains why, in consumer society, we are so

wary of the word "free": we find it difficult to extend

the social market beyond the sphere of family or

friends. As a result, depending on the circumstances,

it may be in one's interest to use the term free, or on

the contrary, one may seek to conceal it - to avoid

suspicion - by insisting more on the idea of freedom

in the proposal instead of the absence of price.

Our study concerns the free aspect of online

training, and in this field, the Internet has contributed

in recent years to restoring a place for free by opening

up access to a large number of unpriced services in

the field of knowledge and training: collaborative

online encyclopaedia (Wikipedia), open source

software, freemiums, MOOCs (although payment is

sometimes made on the certificate), videos and

tutorials on YouTube, etc.

However, what value can one attribute to this free

access? Wikipedia has long suffered - and still

suffers, despite its massive use and recognition by the

scientific community - from its free nature, with a

reputation of being a non-quality product, containing

erroneous information, which should absolutely be

distrusted (Hu et al., 2007). The same applies to free

online training courses: produced with funding other

than that of users, with intentions not always clearly

expressed, they can be the object of distrust.

How can the public, accustomed to gauging the

quality of products through the prism of the money

market, choose quality products if the market value is

not quantified by an explicit price, and if the value

itself - in terms of quality and potential benefit for the

user - is not legible as a result?

In this study, we will therefore look at the extent

to which price can influence a user's decision-making

process when choosing between paid and unpaid e-

learning. Can a free course have the same value and

interest as a paid course in the user's perception? Is

38

Tidey, G., Dedieu, L., Levert, A. and Sakdavong, J.

Free Online Training and Value Perception in France.

DOI: 10.5220/0010977700003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 1, pages 38-48

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

free training a marker in the decision-making process

for choosing a course?

First, we will review the different articles in the

literature related to the notion of free training, in the

purchase decision processes and in the links that can

exist with e-learning. We will then outline the

research methodology used, explaining how we

sought to verify the hypotheses posed before the

survey was carried out for this study. Finally, we will

discuss the results obtained, their significance, and

the new studies that could be carried out to enrich this

theme.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 A Plurality of Representations of

Free Access

2.1.1 State of the Art

To take stock of the situation of free access in our

society is to measure from an economic, but also a

social, ethical or political point of view, what remains

of non-market relations in human affairs.

Caillé and Chanial (2010) recall that this question

was a major issue in the aftermath of the Second

World War when the Universal Declaration of

Human Rights was drafted (1948), particularly with

regard to access to knowledge, education, health and

protection against unemployment. Equality of

opportunity between individuals is conceived as the

mark of unconditional human dignity, and this must

be non-market, and therefore free, the glue of a

society built around an ideal of human progress.

However, Caillé and Chanial (2010) believe that

this idealistic discourse, which seeks to re-enchant the

world in the aftermath of a barbaric conflict, is now

undermined by “the splintering of the discourse on

free access into three totally disjointed, if not opposed

and contradictory, blocks”:

• The first discourse focuses on the fact that nothing

is free in the natural state: global warming proves

that Nature no longer has anything free to offer us

and we cannot count on it. There is therefore a

conflict between those who want to monetise the

depletion of natural goods, for example by using

"rights to pollute", and those who support the need

for negative growth on a global scale.

• Since the 1980s, a second discourse has been put

forward by the proponents of neo-liberalism and

homo œconomicus, sweeping away centuries of

economic and social functioning centred around

the notion of non-profitable exchanges (peasant

cooperatives, hospitals administered by religious

people, etc.): there is no longer any place for free

services in this world, and public services

themselves are destined to give way to a

generalised subjugation to the principle of

financial assets. There is no area where

privatisation has not extended its reach:

education, health, pensions, insurance, energy,

mail, personal services, etc. The spirit of

efficiency and profitability has penetrated into

unsuspected areas, for example through fee-for-

service pricing in French hospitals or the

analytical and normative accounting of the

number of daily reports drawn up by police

officers. Money is no longer a simple means, but

the means “par excellence” and therefore an end

in itself, the universal regulator of human

relations. Caillé and Chanial quote Georg Simmel

(1987): "Money, the absolute means and therefore

the meeting place of innumerable teleological

series, has a significant relationship,

psychologically speaking, with the idea of God...

The profound essence of the divine thought is to

unite in it all the diversities and contradictions of

the world."

• A final discourse is based on the universalization

of free access promoted by the Internet. Numerous

services are freely accessible, without monetary

compensation, whether it be information (articles,

studies, databases, images), open source software,

or search engines, including in the cultural

domain. Is the web the place for community

resistance to the capitalist organisation of the

world, for the invention of a public space

accessible to all and defined as a common good?

For Anderson (2009), an apostle of free software,

there is no doubt about it, "we are entering an era

where free access will be considered the norm and

not an anomaly."

2.1.2 On the Scarcity of Free?

For Grassineau (2010), this original and intrinsic

presence of free on the Internet questions precisely

the widespread presupposition of considering free as

a rare and abnormal phenomenon. For him, on the

contrary, free access, in a Copernican reversal of

perspective, calls into question the reliability and

validity of the dominant beliefs in the orthodox

market economy.

In his study on the case of the Wikipedia project,

he first proposes a descriptive typology of the

different types of gratuity: natural / constraint /

Free Online Training and Value Perception in France

39

networked / commercial. In the latter case, for

example for free newspapers, the economic model is

tripartite: "advertisers pay for the media to reach

consumers, who will make advertisers live."

Anderson (2009)

For Grassineau (2010), gratuity questions our

representation of commitment to work, or even the

entire economy: since on the Internet intrinsic

motivations prevail in collaboration networks (many

Internet users spend hours contributing to the

functioning of Wikipedia, without any remuneration),

why does the labour economy of the whole society

not work on this model?

2.1.3 Free versus Gratuities

The magazine Vacarme, in its issue devoted to free

(n°50, 2010), stresses that we are not dealing with the

general idea of free, but with different gratuities,

which can be classified according to the different

methods of production:

• Free as the production of a non-market sphere in

the economy, conquered thanks to socialized

financing: this is the model of the school, libraries,

hospital, and the very definition of public

services.

• Free access as a refusal of individuals to submit to

the laws of the market - piracy, free software,

cooperative work - "all forms that creep into the

folds of capitalism, develop spaces or undermine

it from within".

• Free as an element of the consumer society and its

sales techniques: free products calling for paid

versions, or financed by advertising or derivative

products.

2.1.4 Free of Charge and Price:

Non-monetary Costs

Free does not necessarily mean disconnected from the

concept of price: what one does not pay with money

can however represent a cost: the time one spends in

a task, whatever it is, the intellectual or physical

efforts that it supposes, the sacrifices or

compensations that are required in the operation, so

many non-monetary costs that the contemporary

economy struggles to quantify and really take into

account.

For example, Le Gall-Ely et al. (2007) studied the

impact of the lack of pricing at the entrance to

museums, and the obstacles that prevent a massive

attendance subsequent to this offer, as it is in the

United Kingdom in National museums, or in France

on the first Sunday of each month or on heritage days:

"Other non-monetary efforts are reinforced, even

created, by gratuity (...). In this context, the free

entrance fee represents only the elimination of one of

the direct monetary efforts of the visit: an absence of

an entry price within an overall price".

If we do not contribute monetarily to a benefit we

receive, we always pay with a part of ourselves: our

time, our attention, our energy.

2.2 Link between Gratuity and Value

It is difficult not to associate the notions of price, cost

and gratuity, with the concept of value... Gratuity is

often perceived as an indication of the intrinsic lack

of value, but the latter term can seem complex to

define precisely.

2.2.1 Exchange Value and Use Value

According to Aurier et al. (2004), value analysis must

be viewed from the consumer's point of view. It is

approached in marketing from two perspectives,

global or analytical, which correspond to the

traditional dichotomy of economists between

Exchange Value and Use Value:

• Exchange value: For Zeithaml (1988), this

corresponds to "the overall assessment of the

usefulness of a product based on perceptions of

what is received and given". What is received is

perceived as a benefit or a profit; what is given

constitutes a set of sacrifices, monetary and/or

cognitive costs. Since evaluation compares

benefits with the sacrifices associated with

consumption, it is therefore the relationship

between benefits and perceived sacrifices

(Grewal, Monroe and Krishnan, 1985). Perceived

value increases with benefits, and decreases with

sacrifices. According to the neoclassical theory of

economics, the "rational" buyer, as a good

calculator, will choose the offer whose value

offers the best compromise.

• Use value: it refers to "a relative preference

(comparative, personal, situational),

characterizing the experience of an individual

interacting with an object" (Aurier et al., 2004).

Extensive experience reduces perceived risk and

limits the search and processing of information.

The consumer will then trust his routines. On the

other hand, a weak experience will lead him to

look for information to cope with uncertainty.

According to more pragmatic and interactionist

theories, value is neither intrinsic to the good itself –

not consubstantial in a way – nor totally subjective,

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

40

even if there are undeniably variations from one

subject to another. It is simply "updated during an

interaction with a subject" (Marion, 2013).

For Baudrillard (1972), quoted by Poels and

Hollet-Haudebert (2013), "once exchange value is

neutralized in a process of giving, free access,

profligacy, expenditure, use value itself becomes

elusive".

As a result, when there is free, the dual

relationship Exchange Value / Use Value disappears

to be replaced by the relationship Sign Value /

Symbolic Exchange Value. The latter can, in the

context of free visits to museums or monuments, be

understood as the social meaning devolved to a good

or service (Bourgeon-Renault et al., 2009): society

speaks through the individual.

2.2.2 Free of Charge and Offer Devaluation

Free of charge often has a depreciative connotation,

and studies show that a zero-price offer will be

perceived as having less value than the same offer in

its paid version (Gorn et al., 1990). Devaluation can

also apply to the perception that the individual has of

himself by using the free service (Prottas, 1981).

For this purpose, Poels and Hollet-Haudebert

(2013) conducted an exploratory study on free

newspapers distributed in the subway, which are

generally considered of lesser quality than those

purchased on newsstands are. Their survey, based on

observation and interviews, shows that readers of

these free newspapers hold a depreciative discourse

on the content, having few expectations of the quality

of the articles; they handle the object itself

unceremoniously, throwing it away very quickly or

abandoning it on a seat. Conversely, paying for a

traditional newspaper marks a commitment and

recognition of the work of others.

More generally, the interviews show that the

social image interferes and that there is a

"contamination" between the newspaper and its

readership: reading only free newspapers is

considered very insufficient by the respondents.

However, these reading media are widely used, and

the authors highlight the paradox of never really

including oneself in the readership of free newspapers

despite the uses.

Against all odds, the most interesting advantages

identified by the authors are not played out from the

point of view of individuals, but more generally from

a social point of view: "The use of free newspapers

gives opportunities for social exchange, thanks to

easy access to information, it is a lever for social

inclusion and enhancement of the social image."

Reading free press makes it possible to maintain a

minimum degree of information necessary for

exchanges around the coffee machine. In addition,

leaving the newspaper on the subway seat allows

other transit users to read it, creating invisible

connections between people.

Moreover, from a societal point of view, the

interviews show that individuals attach great

importance to the culture of free access and that the

newspaper becomes an example of this in the same

way as other cultural goods such as music and films

(which are themselves the subject of collective

reappropriations that are not always legal).

The "devaluation" of the free offer can therefore

be compensated, in the end, by its ability to become a

rewarding marker of a positive social model, based on

the right to information, the democratization of access

to cultural goods and on the notion of sharing.

2.3 Impact of Free Access on

Behaviour and Decision-making

Processes

2.3.1 The Irrational Force of Free Access

Free access has an appeal that simply goes beyond

saving money, and some authors have showed that the

traditional economic theory according to which

people "rationally" choose the option with the

greatest cost-benefit difference is not effective when

free interferes.

Thus, Shampanier et al. (2007) conducted a study

to show the quasi-magical effect of free: during an

experiment conducted on students who are offered a

quality chocolate (Lindt) at 15 cents and another of

lower quality (Hershey's) at 1 cent, 73% of

individuals opt for quality at the expense of the

financial economy; on the other hand, if we maintain

the same difference between the two chocolates (of

the order of 14 cents), but the second is free, 69% of

individuals will choose the latter to take advantage of

the windfall of free, paradoxically willing to eat a

chocolate recognized as inferior and which they did

not want in the first experience.

For the authors, when an object is free, the

perception of losses and sacrifices disappears, along

with the rationality of homo œconomicus: faced with

a choice, people do not simply subtract the costs of

the benefits, but rather perceive the benefits

associated with free products as higher. The zero

price of a good not only cancels out its cost, but also

adds to its benefits.

Free Online Training and Value Perception in France

41

2.3.2 Reduction of Perceived Risk and

Authorisation of Error

Free admission can also remove certain physical and

psychological barriers that hitherto inhibited action,

for example in a museum context: for some visitors,

the process of crossing the doors of a cultural

establishment can be facilitated by the absence of

pricing, and free access thus intervenes in the

decision-making process (Bourgeon-Renault et al.,

2009). The public concerned feels that there is little

"risk" of making a mistake when entering a museum

if it is free, and the negative consequences of a bad

choice are reduced anyway: "Free would act as a

stimulus to the consumer's exploratory trend.

Regardless of the probability of error that may remain

high, this right to trial allows you to enter a museum

or monument simply out of curiosity." (Bourgeon-

Renault et al., 2009)

However, regarding the link between free

admission and museum attendance, all authors of the

literature agree that, without educational and cultural

support, making museums free is not enough to bring

the most culturally distant audiences to this very

specific universe. Free access alone cannot change

the decision-making process in this context.

2.4 Value and Training

Since our study seeks to analyze the impact of free

education on the decision-making process in a

training context, it is necessary to recall here what

makes it possible to measure, according to the

literature, the value of training.

Bourgeois (1998) in his study on engagement in

training refers to the paradigm of expectancy value

developed since the 1970s: "The individual will be all

the more willing to engage in training, to consent to

its costs, that on the one hand, he is sufficiently

convinced that the training envisaged will actually

bring him benefits (and that these are sufficiently

important, for him), and that on the other hand, he

considers his chances of success in the company

sufficiently high."

The estimation of the value of a training strongly

depends on the benefits perceived by the user for his

life, at a given moment in his trajectory. Let us recall

the four categories of motivations listed by Biggs and

Moore (1981) to qualify these perceived benefits,

cited by Bourgeois (1998): extrinsic / social / related

to self-fulfillment / intrinsic motivations.

The reputation of a training institution can help

create a positive expectation and increase the value

that can be attributed to training, to minimize

uncertainties during the upstream evaluation process.

Thus, the public is still interested in the many judging

devices - such as the Shanghai ranking - that compare

and prioritize educational institutions with each other,

in order to infer a "value" of the training offered, even

if it is clear that the classification operation has itself

become a commercial institution (Mignot-Gérard and

Sarfati, 2015).

In reality, how can one presume the value of a

proposed training, especially if one does not have

information on the context or on the reputation of the

training organization that delivers it?

Faced with a new offer, we can think that the user

will use his imagination - subject to many influences,

and constantly reconfigured - to make a value

judgment according to the possibilities of action of a

good (its updatable performance) and the sacrifices it

implies.

Rivière (2015) demonstrates, however, in a

quantitative study conducted among 828 individuals

on the public's perception of new offers in the

automotive sector, that upstream of the adoption

process, the perceived value of a novelty is only

influenced by its perceived benefits: it is not affected

by the perception of the sacrifices to be made. The

glare caused by novelty seems to stand in the way of

considerations perceived as unpleasant, and reason

has difficulty interfering when seduction operates

(which intuitively, one would tend to consider as

generalizable beyond the simple field of the

automotive sector...).

2.5 Overview

It is difficult to find in the literature studies on the

perception of the quality of free online training,

because the concept of free training is sometimes

considered as the prerogative of the public sector (and

the question of free training is quickly evacuated as

self-evident), and sometimes closely associated with

marketing strategies in the private sector (freemiums,

loss leaders and samples), which is not the model

proposed by the company concerned by this research,

as the user of the training is never financially

solicited.

On the other hand, some of the studies dealing

with the notion of price in online education concern

university models that involve collaborative practices

between students, which are rewarding and which

therefore lead students to consider that content and

interactions are more important than price. Again, this

is not the model we propose to study, since the

company in question here offers individual training

with very limited interaction.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

42

Moreover, studies on free education often concern

objects, and more rarely services. It is therefore very

difficult to consider training as a consumer good like

any other, since the non-monetary costs of any

training are at least as important as the monetary

costs: training requires effort, or even a total

commitment on the part of the user; there is no such

thing as "passive" consumption. Buying a course is

just giving oneself the opportunity to start the

learning process.

Finally, the problem of uncertainty remains a

thorny one in the decision-making process: how can

a course be evaluated before the course itself has been

experienced? The user's perception of training

courses (free or paid) and of the value he or she may

attach to them (and therefore of his or her future

commitment to learning) is based on subjective

criteria and previous experiences, and the user's

evaluation often consists of trying to compensate for

the uncertainty as best he or she can, by betting that

his or her choice is judicious.

It therefore seems necessary to take an interest in

this evaluation upstream of the training, which the

future user undertakes, and to measure the link or

influence that the price may have on the perception

that one has of this training, from the point of view of

its quality and in terms of the benefits that one can

hope to obtain from it.

2.6 Research Hypotheses

First of all, since free of charge can have a

depreciatory connotation and a zero price offer can be

perceived as having less value than the same offer in

its paid version (Gorn et al., 1990; Poels and Hollet-

Haudebert, 2013), we will try to verify the influence

of the price in the qualitative evaluation made by the

user in the context of the decision-making process of

a training choice.

We therefore put forward an initial hypothesis as

follows: The more expensive a training course is, the

more it is considered as qualitative by the user (H1).

In this hypothesis, the factor is the price, and the

Dependent Variable (DV) is the quality appreciated

by the user. The factor and DV will be varied

according to ordinal scales.

Furthermore, we have seen in the literature review

that the zero price exerts an irrational force in the

purchasing decision process (Shampanier et al.,

2007). Since this effect leads to the benefits

associated with free products considered higher than

when they are paid for, we will try to verify that this

effect can be exerted in the same way when the user

evaluates the hypothetical benefits of a training

course.

We therefore put forward a second hypothesis as

follows: When the price of a training course is equal

to zero, the benefit can be considered by the user as

higher than that of a paid training course, even a

cheap one (H2).

In this hypothesis, the factor is the price, and the

Dependent Variable (DV) is the benefit assessed by

the user. The factor and DV will be varied according

to ordinal scales.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Participants

In order to collect sufficient data to achieve our

research objectives, an internet survey was conducted

among a population that does not have an account on

the company's platform My Green Training Box

(from which the videos used were taken) and

therefore cannot recognise the online video trainings

used in the survey, so as not to be influenced in their

answers.

The survey was conducted via the internet through

LimeSurvey during July 2021. More than 500 people

were contacted by email or social networks. No

selective recruitment was carried out. 143 women and

102 men responded to the survey.

Data is securely and anonymously stored on the

LimeSurvey server at the University of Toulouse, in

compliance with the General Data Protection

Regulation.

3.2 Experimental Set-up

3.2.1 Basic Set-up

After the usual questions on the identification of

participants (gender, age, socio-professional

category, experience of online training) and

individual consent to take part in this survey

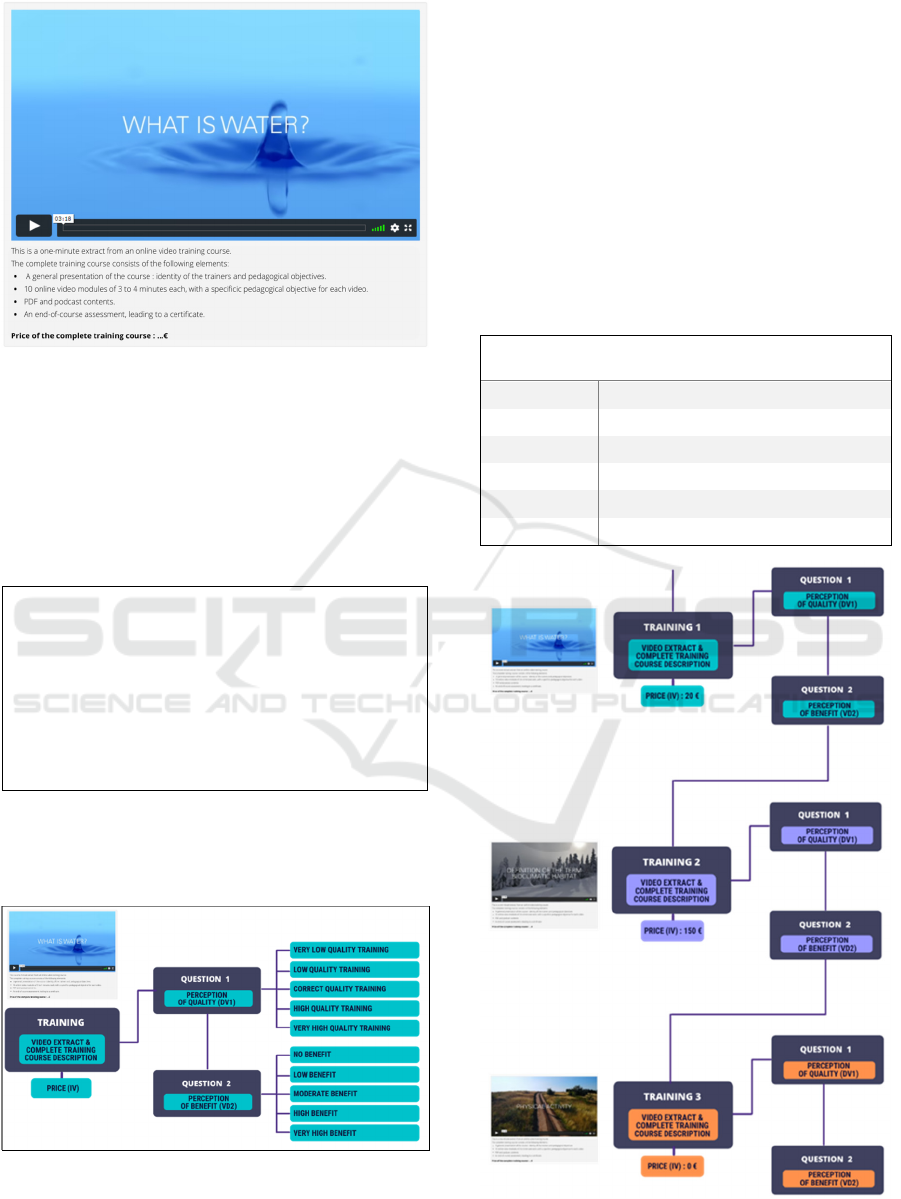

anonymously, the system offers to watch a one-

minute video presented as an extract from an online

video training course.

Underneath the video is a description of the

complete training course, consisting of a general

presentation, 10 video modules of 3 to 4 minutes

each, accompanied by PDF files and podcast

contents, and an end-of-course assessment, leading to

a certificate. The price of the training is mentioned

below, chosen among these three values: 0 € (free

training), 20 € (cheap one), 150 €.

Free Online Training and Value Perception in France

43

Figure 1: Description of the course.

Two compulsory questions follow this

presentation, one on the perception of the quality of

the proposed training, the other on the general benefit

(personal, financial, etc.) for the user of attending this

training

For each question, the participant is asked to give

his or her opinion on a 5-point Likert scale as follows:

According to these criteria, what is your

perception of the quality of this training?

Very low quality training / Low quality

training / Correct quality training / High

quality training / Very high quality

training.

In your opinion, what can be the general

benefit (personal, financial...) for the

user to follow this training? No benefit /

Low benefit / Moderate benefit / High

benefit / Very high benefit.

Figure 2: Scales for quality and benefit.

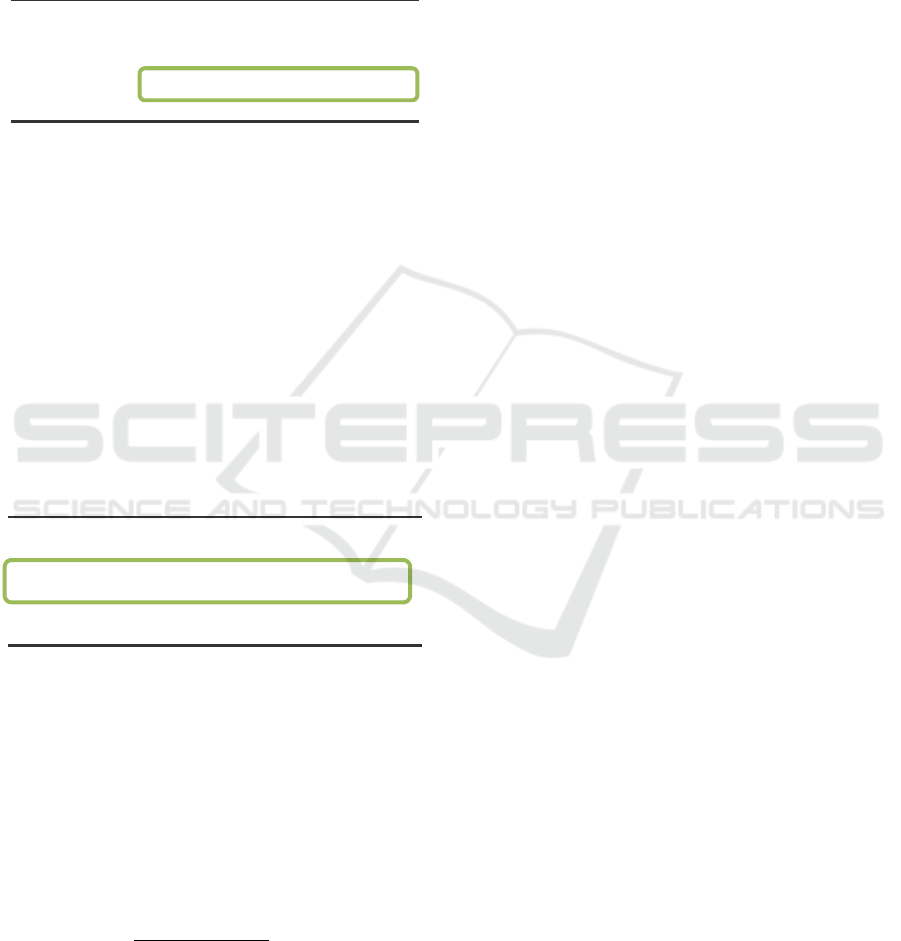

The basic set-up can be summarised as follows

(Figure 3):

Figure 3: Basic set-up.

3.2.2 Extended Set-up

In order to obtain more data and to avoid the results

being dependent on a single training video, the basic

set-up is repeated three times for each participant.

Three different video extracts of equal quality and

length are used from online training courses offered

by the company My Green Training Box on

sustainability-related topics (water, habitat, health),

with all identifying marks (logos) removed.

For each of the three training courses, the price

varies according to the three values (0 €, 20 €, 150 €)

Table 1: Combinations.

COMBINATIONS TRAINING 1 TRAINING 2 TRAINING 3

1

0 € 20 € 150 €

2

0 € 150 € 20 €

3

150 € 0 € 20 €

4

150 € 20 € 0 €

5

20 € 0 € 150 €

6

20 € 150 € 0 €

Figure 4: Example of extended set-up.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

44

corresponding to the general modalities chosen for

the experimentation (free / cheap / expensive

training). The order effect is counterbalanced.

This results in the example of an extended scheme

for one participant below (Figure 4). The example

used in Figure 4 corresponds to combination 1 in

Table 1.

All answers are compulsory, but participants can

go back in the questionnaire and change their

previous answers, once they have understood that the

price varies from one course to another.

Since the three videos are considered equivalent,

the data obtained from the three training courses will

be aggregated for the analysis, after checking that

there is no influence of the training video or the order

of presentation on the responses.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Sample

Of the 500 participants approached, 245 people

completed the survey. From this sample, a profile can

be drawn up with the following characteristics.

A majority of women responded to the survey,

143 versus 102 men. The average age of the

participants is 52 years (50.5 years for women, 54.5

years for men).

The most represented socio-professional category

is managers and professionals (32%), followed by

retirees (24%) and employees (16%).

In the sample, half of the participants have never

taken online training, although the proportion is lower

for women (45%, compared to 57% for men).

4.2 Descriptive Processing of Data

The price factor and has three values/modalities

(150 € = expensive / 20 € = cheap / 0 € = free); the

DVs are called “Training Quality” and “Training

Benefit”; each has 5 modalities, coded from 0 to 4 for

the statistical analyses.

It can be seen initially that the median for the three

price groups is at the level of the intermediate

modality 2 (Correct Quality / Moderate Benefit), as

can often be seen in a 5-point Likert scale (Min 0 –

Max 4). When in doubt, participants often respond

with a value that is not binding on them and that they

consider neutral.

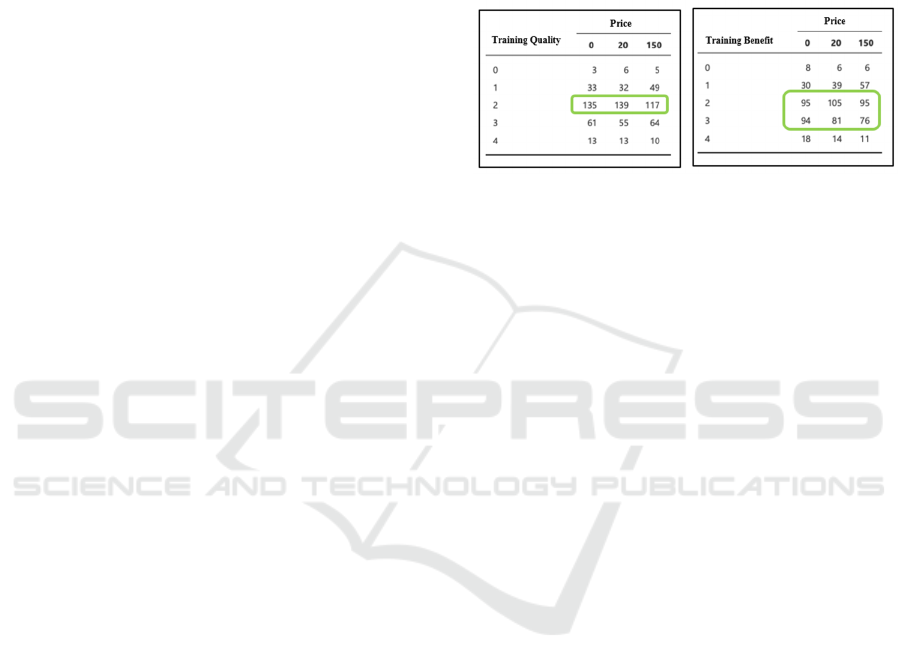

When we look at the frequencies (Tables 2 and 3),

we can see that the perception of the quality of a

training course does not systematically lead to a

perception of the benefit according to the same

modality: thus, while the perception of the quality of

the training courses presented is mostly perceived as

correct (and therefore centred around modality 2 -

Correct quality - of the DV Training Quality), the

responses concerning the benefit provided by these

same training courses are more dispersed over

modalities 2 (Moderate benefit) and 3 (High benefit).

Tables 2 and 3: Frequencies.

This suggests that a training course judged to be

correct (modality 2) may provide a greater benefit

than moderate (modality 2), whereas intuitively one

might think that there is a systematic correlation

between the perception of quality and the benefit that

can be expected from it (the greater the quality, the

greater the expected benefit).

The dispersion of values increases as the price of

the training increases. In our sample, the price does

not appear to be a guarantee for the participants,

either in terms of quality or in terms of general

benefit.

4.3 Inferential Statistics

In order to evaluate our hypotheses and to generalise

the results of our sample to the whole population, we

carry out a rank comparison test between the groups

0 € / 20 € / 150 €, which correspond to the

3 modalities of the main factor.

Since all the variables are ordinal and the 3 groups

can be considered as independent, we carry out a non-

parametric ANOVA with the Kruskal-Wallis test.

The ANOVA is one-sided, since we assume the

existence of a difference in one direction only (an

effect of price on the perception of quality and

expected benefit). We are looking for the ratio

between the inter-group variance and the intra-group

variance.

Since the three groups are considered independent

samples, independence is respected within the

groups, and the measurement scale is ordinal, the

conditions for using the test are respected.

Care is taken to check that the training course

(whose content is identified by a number) and the

order of presentation have no effect on perceived

quality and benefit, also by means of a non-

Free Online Training and Value Perception in France

45

parametric ANOVA, in order to aggregate the data

from the three training courses.

The following results are in table 4:

Table 4: Non-parametric ANOVA about price over quality

and benefit.

χ² df p ε²

Training

Quality

1.36

2

0.506

0.00185

Training

Benefit

8.56

2

0.014

0.01166

There is a significant effect of price over the Training

Benefit measure (p=0.014). On the Training Quality,

there is no significant effect (p=0.506).

The strength of the experimental effect is

measured by the proportion of variance in the benefit

explained by the price and is denoted by the epsilon

squared, which is 0.01166 here. We can conclude that

the effect of the price on the perceived Training

Benefit is small, but it does exist.

The sample pairs are compared for the DV

Training Benefit using the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-

Fligner test (Table 5).

Table 5: Pairwise comparison test.

W p

0

20

-2.14

0.284

0

150

-4.08

0.011

20

150

-2.09

0.303

The effect of the price on the perception of the

Training Benefit is visible and generalizable between

the values 0 € and 150 €.

The hypothesis is partially verified for the

Training Benefit, which allows us to confirm the first

part of H2: When the price of a training course is

equal to zero, the benefit can be considered by the

user as higher than that of a paid training course.

The second part of H2 (When the price of a

training course is equal to zero, the benefit can be

considered by the user as higher than that of a paid

training course, even a cheap one.) cannot be verified

here: there is no significant difference in the

perception of benefit between training courses at 0 €

and 20 €, nor between training courses at 20 € and 150

€.

Detailed analysis not exposed here make it

possible to identify more precisely the factors that

influence the general result, thus confirming our

hypothesis H2. Women over 50 years of age, not

belonging to the category of executives and higher

intellectual professions, attach the most importance to

the difference in price between paid training, even if

it is not very expensive, and free training, when it

comes to measuring the general benefit that this may

represent for the user.

5 DISCUSSION

The results of our study show that there is no evidence

of a significant influence of the price of a training

course on users' perception of the quality of an online

training course: it is not because a training course is

presented as expensive that it is perceived as more

qualitative than a training course presented as free; a

free training course does not therefore seem to be

perceived as less qualitative than a paid course. In the

sample itself, the statistics even tend to show the

opposite effect. In this sense, our first hypothesis is

not verified: it cannot be said that price has a clear

influence on the value attributed to a training course;

it is not because a training course is expensive that it

is necessarily considered as qualitative by the user.

As regards the general benefit that a user can

expect to derive from an e-learning course, our study

shows the presence of a slight effect of price on this

perception of benefit for the future learner: if the e-

learning course is presented as expensive, the general

benefit appears to be less important. A free course is

more interesting from this point of view for the user,

which allows us to verify a large part of our second

hypothesis: when the price of a course is equal to

zero, the benefit can be considered by the user as

greater than that of a paid course.

However, the existence of the “zero effect” cannot

be verified by comparison with a low price, as

described by Shampanier et al. (2007). It seems that

the perception of benefit for the online courses

proposed here is based more on the contrast between

the free courses and the more expensive ones: the

"zero effect" only works in this context, as far as our

study is concerned.

Various explanations can be found for the fact that

free education does not seem to influence the

perception of quality in e-learning, contrary to what

can be found in the literature on the devaluation

suffered by e.g. free newspapers (Poels and Hollet-

Haudebert, 2013).

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

46

It is assumed that part of the public is used to

learning on the internet, for example by looking for a

way to perform a specific task by watching a free

tutorial on social networks. Online resources offer the

possibility to develop one's knowledge and skills in

an unlimited and independent way, without

considering direct monetary costs (one still has to pay

to access the internet). Price may not be an important

factor in the decision making process of Internet users

when choosing an online resource to learn how to

perform a task or obtain specific information.

We can also consider that the study itself -

proceeding by iteration - has induced a form of

"levelling": the same training format having been

offered three times to each participant (since we only

vary the price), one can consider that the 3 successive

training courses are similar and thus no longer pay

attention to the price. Moreover, the 5-point Likert

scale often leads to choose the middle option as a

"neutral" solution, to avoid having to make a clear

statement. The solution would be to ask participants

about a single course (instead of 3), still with a

random price, with a 4 or 6 point Likert scale, to avoid

this repetition and levelling effect.

We could also check the participants' level of

knowledge about the topic addressed in each video,

as well as the impact that this video may have on this

specific knowledge: both elements could have an

influence on the two DVs.

As far as the perceived benefit is concerned, our

hypothesis H2 is partially verified and goes in the

direction of the literature, which considers that there

is an additional and irrational benefit consubstantial

with free access. However, we can recognise that the

effect is quite small for our study and seems to be

limited to one category of people, women over 50

years old and non-managers: are they less used to

online training? Are they more sensitive to spending

money wisely? One can also wonder whether the

perception of "cheap" / "expensive" varies according

to socio-professional categories.

Furthermore, the way in which the questionnaire

was conducted - via the Internet - only allows it to be

addressed to a category of people who are used to

using this method of communication. It should also

be remembered that the questionnaire was not fully

completed by some of the people contacted.

It is regrettable that there are few studies on the

impact of free access on the decision-making process

for digital training. However, there is no doubt that

online training is becoming increasingly important

due to the health crisis, and in order to be trained, one

has to make a choice among all the proposals.

Whether we like it or not, free education is closely

associated with the notion of training: state schools

have instilled the legitimacy of access to knowledge

in us at a very early age. Lifelong learning is therefore

a right, and free education is an important modality,

which research will certainly explore in the years to

come.

6 CONCLUSION

Our study has shown that the price of an e-learning

course does not necessarily influence the value that

the user attributes to it, and that a free course can have

the same value and interest as a paid course.

Moreover, free training is a significant marker in

the decision-making process, and our study has

shown this in the second hypothesis put forward and

partially verified: free training confers an additional

benefit to the training, which goes beyond the simple

monetary savings made compared to the same paid

offer. As a result, free training can give the user the

perception of a greater general benefit than paid

training.

It is therefore tempting to say that there is no

reason to doubt the "value of free training" in digital

training, and that it may be an interesting

development model for companies not to make their

users pay the online training courses they create.

What remains now is to convince funders of the

benefits of contributing to a social model based on the

foundation of free education - a benefit that would

take the form of a supplement of soul.

REFERENCES

Anderson, C. (2009). Free: The Future of a Radical Price.

https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.47-2102

Ariely, D., & Shampanier, K. (2006). How Small is Zero

Price? The True Value of Free Products (SSRN

Scholarly Paper ID 951742). Social Science Research

Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.951742

Ariely, D., Gneezy, U., & Haruvy, E. (2018). Social Norms

and the Price of Zero. Journal of Consumer

Psychology, 28(2), 180-191. https://doi.org/

10.1002/jcpy.1018

Aurier, P., Evrard, Y., & N’Goala, G. (2004). Comprendre

et mesurer la valeur du point de vue du consommateur.

Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 19(3), 1-20.

Bourgeois, É. (1998). Apprentissage, motivation et

engagement en formation. Éducation Permanente :

Parution n°136—1998-3—Motivation et engagement

en formation.

Free Online Training and Value Perception in France

47

Bourgeon-Renault, D., Gombault, A., Le Gall-Ely, M.,

Petr, C., & Urbain, C. (2007). Gratuité des musées et

valeur perçue par les publics. La Lettre de l’OCIM, 111,

31-39. https://doi.org/10.4000/ocim.764

Bourgeon-Renault, D., Gombault, A., Le Gall-Ely, M.,

Petr, C., & Urbain, C. (2006). Gratuité et processus de

prise de décision dans le domaine culturel : Le cas des

musées et des monuments | Association Française du

Marketing.

Caillé, A., & Chanial, P. (2010). Présentation. Revue du

MAUSS, n° 35(1), 5-44. https://www.cairn.info/revue -

du-mauss-2010-1-page-5.htm

Coutelle-Brillet, P., Gall-Ely, M. L., & Urbain, C. (2013).

Gratuité et prix, nouvelles pratiques, nouveaux

modèles. Revue française de gestion, N° 230(1), 77-81.

Gall-Ely, M. L., Urbain, C., Bourgeon-Renault, D.,

Gombault, A., & Petr, C. (2008). La gratuité : Un prix !

Revue française de gestion, n° 186(6), 35-51.

Gall-Ely, M., Urbain, C., Gombault, A., Bourgeon, D., &

Petr, C. (2007). Une étude exploratoire des

représentations de la gratuité et de ses effets sur le

comportement des publics des musées et des

monuments. Recherche et Applications Marketing, 22.

https://doi.org/10.1177/076737010702200202

Gorn, G. J., Tse, D. K., & Weinberg, C. B. (1991). The

impact of free and exaggerated prices on perceived

quality of services. Marketing Letters, 2(2), 99-110.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00436031

Grassineau, B. (2010). Rationalité économique et gratuité

sur Internet : Le cas du projet Wikipédia. Revue du

MAUSS, n° 35(1), 527-539.

Grewal, D., Monroe, K. B., & Krishnan, R. (1998). The

Effects of Price-Comparison Advertising on Buyers’

Perceptions of Acquisition Value, Transaction Value,

and Behavioral Intentions. Journal of Marketing, 62(2),

46-59. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252160

Lalande, A., & Patouillard V. (2010). Gratuités. Vacarme

50 / Défendre la gratuité. https://vacarme.org/

article1842.html

Heyman, J., & Ariely, D. (2004). Effort for Payment A Tale

of Two Markets. Psychological science, 15, 787-793.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.0 0757.x

Hu, M., Lim, E.-P., Sun, A., Lauw, H. W., & Vuong, B.-Q.

(2007). Measuring article quality in wikipedia : Models

and evaluation. Proceedings of the sixteenth ACM

conference on Conference on information and

knowledge management, 243-252. https://doi.org/

10.1145/1321440.1321476

Leonard Lee, Bertini, M., & Ariely, D. (2009). Money

Muddles Thinking: The Effects of Price Consideration

on Preference Consistency. ACR North American

Advances, NA-36.

Marion, G. (2013). La formation de la valeur pour le client :

Interactions, incertitudes et cadrages. Perspectives

Culturelles de la Consommation, 3, 13-46.

Mencarelli, R., & Rivière, A. (2012). Vers une clarification

théorique de la notion de valeur perçue en marketing.

Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 27, 101-128.

https://doi.org/10.1177/ 076737011202700305

Mignot-Gérard, S., & Sarfati, F. (2015). Dispositif de

jugement sur la qualité ou instrument de construction

de la réputation ? Terrains travaux, N° 26(1), 167-185.

Poels, A., & Hollet-Haudebert, S. (2013). Valeur(s) et

pratiques associées à la consommation de journaux

gratuits. Revue française de gestion, N° 230(1),

119-135.

Prottas, J. M. (1981). The Cost of Free Services:

Organizational Impediments to Access to Public

Services. Public Administration Review, 41(5),

526-534. https://doi.org/10.2307/976263

Rivière, A. (2015). Vers un modèle de formation de la

valeur perçue d’une innovation : le rôle majeur des

bénéfices perçus en amont du processus d’adoption.

Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 30, 5-27.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0767370114549908

Sagot-Duvauroux, JL. (1995, 2006). De la gratuité.

http://www.lyber-eclat.net/lyber/sagot1/gratuite.html

Shampanier, K., Mazar, N., & Ariely, D. (2007). Zero as a

Special Price: The True Value of Free Products.

Marketing Science, 26(6), 742-757.

https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1060.0254

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer Perceptions of Price,

Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis

of Evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2-22.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1251446

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

48