Using Lean Personas to the Description of UX-related Requirements: A

Study with Software Startup Professionals

Gabriel V. Teixeira and Luciana A. M. Zaina

Federal University of S

˜

ao Carlos (UFSCar), Sorocaba, S

˜

ao Paulo, Brazil

Keywords:

Lean Personas, User Experience, UX, Software Requirements, Software Practitioners, Software Startups,

Empirical Study.

Abstract:

User experience (UX) is a quality requirement widely discussed by software developers. Organizations have

targeted to offer software features that carry value to the audience. For software startups, UX-related re-

quirements can represent a competitive edge in their fast-paced environment with constant time pressures and

limited resources. However, software startup professionals often have little experience and lack knowledge

about UX techniques. Lean persona technique emerges as a slim form of constructing personas to allow the

description of end-users needs. In this paper, we investigated the use of the lean persona technique with 21

software professionals, 10 and 11 from software startups and established companies respectively. We carried

out a comparison to see whether the startup professionals use the technique in a different way from the estab-

lished company professionals. Our results revealed that the professionals of both groups used the technique

for similar purposes and wrote up UX-related requirements in different levels of abstraction. They also re-

ported positive feedback about the technique acceptance. We saw that the participants’ characteristics as years

of experience, prior knowledge about personas technique, or the fact of working in startups did not have an

influence on the technique acceptance.

1 INTRODUCTION

User experience (UX) is an important aspect of soft-

ware quality that affects software acceptance by the

users (Ohashi et al., 2018). The interaction needs of

the end-users with the software thus have to be taken

into account during the software production. Even

though there are different definitions of UX, most of

them state that UX encompasses both the software

functionalities and its quality characteristics that are

perceived by end-users during their interaction (Has-

senzahl, 2018). Usually, all software products deliver

some experience to the end-users that can result in a

positive or negative UX (Kashfi et al., 2017; Ohashi

et al., 2018; Zaina et al., 2021).

The topic of UX is not new in the software engi-

neering area. Practitioners and researchers have in-

vestigated challenges and problems in incorporating

UX in software development over the years (Kashfi

et al., 2017; Da Silva et al., 2018; Zaina et al., 2021).

The literature points out that there is a gap in stud-

ies about how tools can effectively help software pro-

fessionals to deal with UX in software development

practices (Da Silva et al., 2018). Recently, Zaina et

al. (2021) discuss the need to adopt techniques and

methods that support software professionals in iden-

tifying UX information that can aid in the software

development. Kashfi et al. (2017) reported that soft-

ware engineering professionals face barriers to incor-

porating UX into software processes. The literature

has pointed out that software professionals have dif-

ficulties in the elicitation activity for UX-related re-

quirements more than for functionality or other qual-

ity characteristics (Kashfi et al., 2017; Sch

¨

on et al.,

2017; Choma et al., 2016). UX-related requirements

describe and inform user needs (Hassenzahl, 2018).

For software startups, UX-related requirements

are relevant due to the experience with the product

being a factor that affects the user’s decision about

the use or not of products (Hokkanen et al., 2016).

Startups are companies with a focus on developing

innovative products or services (Paternoster et al.,

2014). These organizations differ from established

companies by searching for a scalable, repeatable,

and profitable business model with the aim of grow-

ing in the market (Paternoster et al., 2014). Startups

can work in different areas; however, they are char-

acterized by producing software or making intense

Teixeira, G. and Zaina, L.

Using Lean Personas to the Description of UX-related Requirements: A Study with Software Startup Professionals.

DOI: 10.5220/0011033200003179

In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2022) - Volume 2, pages 211-222

ISBN: 978-989-758-569-2; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

211

use of software to manage their activities (Giardino

et al., 2014). These companies often operate with

a small team of professionals, exploring new tech-

nologies, being marked by rapid evolution, high un-

certainty about customers and market conditions, and

high failure rate (Paternoster et al., 2014). The liter-

ature has emphasized the relevance of studies about

software development practices to better support the

software practitioners in the fast-paced environment

where startups operate (Giardino et al., 2014). More-

over, startups software professionals usually are new-

comers with little professional experience and due to

this they struggle on using different software meth-

ods and techniques (Paternoster et al., 2014; Giardino

et al., 2014). These difficulties are extended to the

use of UX methods and techniques (Hokkanen et al.,

2016).

UX-related requirements elicitation has been con-

ducted with the support of different techniques, and

the Personas technique is one of them (Faily and

Lyle, 2013; Castro et al., 2008). The personas tech-

nique provides a process for creating personas arti-

facts from the analysis of end-user data. These arti-

facts present fictional characters that represent the dif-

ferent user types that can use a service or product and

help the software practitioners to understand users’

needs, experiences, behaviors, and goals (Billestrup

et al., 2014a). However, the traditional persona con-

struction is often seen as a costly technique in terms

of time, and effort (Billestrup et al., 2014b). Gothelf

proposes a leaner process for developing personas,

called proto-personas and also known as lean per-

sonas (Gothelf, 2012). The process allows the cre-

ation of personas artifacts based upon prior knowl-

edge that the practitioners have about the target audi-

ence (Gothelf, 2012).

Lean personas is a technique that can be suitable

for startup needs of adopting leaner practices that de-

mand few resources and time to be used (Paternos-

ter et al., 2014). However, little has been explored

about the use of these lean UX practices by startup

professionals. To address this, we investigate the fol-

lowing research questions: (RQ1) What type of UX-

related requirements do software startup profession-

als describe by using lean personas technique?; and

(RQ2) What are the participants’ feedback about the

use of lean personas technique?

To answer the RQs, we conducted a study with

21 software professionals, 11 from established com-

panies, and 10 from software startups, who built

lean personas artifacts to describe UX-related require-

ments. The participants worked in software compa-

nies from diverse segments (e.g., financial, health) in

Brazil. They occupied development-related positions

(e.g. product owners, software engineers, develop-

ers). From the data collected, we compared the re-

sults of the two groups to understand whether there

were differences in the use and acceptance of the

lean persona by professionals from startups and es-

tablished companies. Our decision of comparison is

due to the fact that the literature points out that startup

professionals have little experience and usually have

demands for techniques and tools that are more ad-

herent to the startup context. We examine the lean

personas produced by the participants looking for ev-

idence on descriptions of UX-related requirements to

analyze the use of the technique. We also collected

participant acceptance of the technique’s use from an

online questionnaire.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 User Experience

In general, the literature states UX as the

user/customer interaction with the product and

company (Lallemand et al., 2015). In a different

perspective, Hassenzahl (2018) points out that the

user experience is related to the users’ motivation

when interacting with a product. According to the

author, users are motivated by goals they want to

achieve, and these goals, in turn, guide the user’s

interactions with a product.

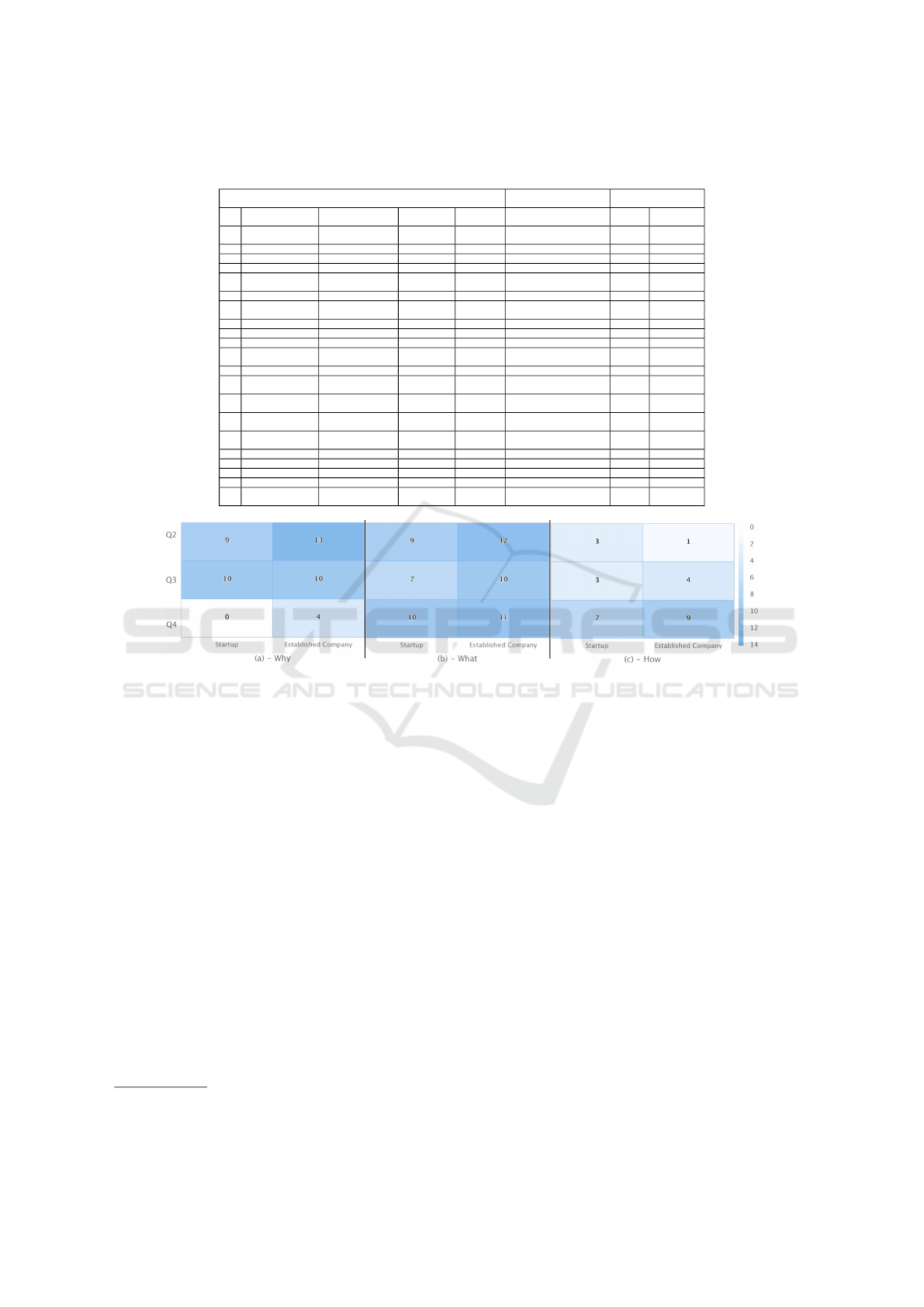

Hassenzahl formalizes UX definition in a content-

oriented model which contains three levels of interac-

tion action, i.e., ‘why”, “what” and “how” and a goal,

that is to achieve the “wellbeing” of users (see Figure

1). The “why” level focuses on the meaning that the

interaction can provide for users; it discusses the mo-

tivations and needs that lead the user to use the prod-

uct. The “what” level defines the functionalities that

the product offers to the users to fulfill their needs.

The “how” level explores the concrete actions of the

users for interacting with the product, e.g. clicking

on a button or reading instructions. We decided to

adopt the content-oriented model of UX in our study

because our focus is on identifying the specifications

about UX that were described from the lean personas.

We consider that this model provides concrete ele-

ments to support our analysis instead of other abstract

definitions of UX.

2.2 Related Work

The personas technique has been used to support

software teams in the identification of end-users re-

quirements. An investigation with 60 software com-

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

212

Figure 1: Content-oriented model of UX adapted from

(Hassenzahl, 2018).

panies showed that only 7 of them used this tech-

nique (Billestrup et al., 2014b). The companies that

did not use the technique recognized it as relevant for

identifying end-user requirements. However, they re-

ported not being able to use it in their daily work due

to problems such as lack of knowledge about how to

apply the technique, lack of time, and lack of finan-

cial resources (Billestrup et al., 2014b). In another

work, software engineers reported that the personas

technique not only allows a better understanding of

the user’s needs, but it also supports these require-

ments being elicited up-front to the design and coding

activities (Sim and Brouse, 2014).

The results about the effectiveness and efficiency

of adopting personas artifacts during requirements

identification was presented by Salmien et al. (2020) .

The authors compared the use of personas with re-

quirements elicitation made using available data in an

analytics tool (Salminen et al., 2020). The results re-

vealed that the developers spend more time on iden-

tifying the requirements which were caused by the

need of interpreting a great amount of data and graph-

ics available from the analytics tool. On the other

hand, the personas artifacts presented end-user data

in a straightway which make the developers work be-

come faster (Salminen et al., 2020).

PATHY technique was proposed to help develop-

ers identify requirements (Ferreira et al., 2017). Its fo-

cus is to help software engineers recognize user char-

acteristics and present an overview of product func-

tionality. PATHY is an adaptation of the empathy

map, which is a variation on the persona technique.

Its differential is a set of guideline questions that

guide the development team to build personas that ad-

here to the target audience (Ferreira et al., 2017).

Pinheiro et al. (2019) proposed the Proto-

Persona+, which is an extension of the proto-persona

technique proposed by Gothelf (2012). Similar to

the PATHY, the Proto-persona+ provides guideline

questions to support personas’ construction. The au-

thors conducted a study in which the use of proto-

personas proved to be effective for eliciting UX re-

quirements with the participation of software engi-

neers and domain experts. The results also showed

that the proposal contributed to both software engi-

neers and domain experts writing UX requirements

relevant to software development.

The literature above shows evidence of the rele-

vance of personas technique for requirements elici-

tation. However, as far as we know, no studies in-

vestigate the use of the personas technique by startup

software professionals. In particular, we argue that

the lean UX techniques such as lean persona are more

suitable for software startups where few resources are

available, and professionals often have little experi-

ence (see discussion in Section 1).

3 LEAN PERSONA

Gothelf (2012) proposes the lean persona technique,

also known as proto-persona, as an agile and low-cost

alternative for creating personas. The main difference

between the traditional persona and the lean persona

is the order of executing of the steps for its construc-

tion (Gothelf, 2012; Billestrup et al., 2014a). Rather

than building the personas based on a broad demo-

graphic and profile survey of end-users, lean personas

are built by taking into account the prior knowledge

that the software professionals have about the end-

users (Gothelf, 2012).

The lean personas are constructed during work-

shops that were conducted by a moderator who is an

expert on this technique application with the partici-

pation of software professionals. First, the lean per-

sonas can be built individually by the software profes-

sionals. Later, the workshop participants examine all

the lean personas and they together refine them to pro-

duce a reduced number of personas. In an extension

of Gothelf’s proposal, Pinheiro et al. (2019) present

the Proto-Persona+, an quadrant-based approach pro-

posal to constructing lean personas. Proto-Persona+

features a four-quadrants template to enhance the de-

scription of users’ information whereas keeping the

characteristic of being a lean artifact.

The four quadrants have the following functions:

(Q1) Demographic data contains the users’ charac-

terization relevant to the development of the product,

including an image that represents the persona; (Q2)

Objectives and needs presents the users’ goals and

the needs to achieve these goals; (Q3) Behaviors and

preferences show details of how the user likes to carry

out tasks to achieve their goal, and their preferences

regarding contents and interaction modes; and (Q4)

Difficulties point out the user’s difficulties and frustra-

Using Lean Personas to the Description of UX-related Requirements: A Study with Software Startup Professionals

213

Figure 2: Lean persona tool.

tions the users can have during their interacting with

the product. To guide the personas elaboration, the

Proto-Persona+ approach provides a set of guideline

questions for each quadrant.

According to Pinheiro et al.(2019), there is a

dilemma about the use of personas technique by soft-

ware professionals. While the personas technique

is recognized as useful by these professionals, they

often struggle in putting this technique into prac-

tice (Billestrup et al., 2014b). Besides, sometimes the

personas present information that was not relevant to

the development scope (e.g. hobbies, personas’ pets)

which can cause a miscommunication about the core

requirements (Billestrup et al., 2014b). In this way,

the guideline questions help software professionals to

focus on descriptions that fulfill the goals of the quad-

rants and keep the attention on the important require-

ments. Pinheiro et al. (2019) state that their proposal

is flexible by allowing to the addition of other guide-

line questions under demand.

In our study, we decided to adopt the proposal

of Pinheiro et al. (2019) due to it provides a tem-

plate and guideline questions which guide the soft-

ware professionals on the artifacts construction. Be-

sides, the authors proposal have been evaluated to the

UX requirments specifications previously. Based on

the Pinheiro et al. proposal, we developed the lean

persona tool (see Figure 2). The tool automates and

makes easy the use of the Proto-Persona+ technique.

The lean persona tool provides two views, one for the

moderator of the session to the personas construction

and the other for the participants, i.e. software pro-

fessionals, to fulfill the template and thus produce the

personas artifact.

The tool provides the moderator with a project-

based organization (see Figure 2(a)). For each project,

the tool delivers the default template which contains

the guideline questions (see Figure 2(b)). New guide-

line questions can be added or the available ones can

be modified. After preparing the template, the moder-

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

214

ator makes it available for the participants of the ses-

sion of the lean persona creation from a link generated

by the tool (see sharing link field in Figure 2(a)). The

participants then create the lean personas, individu-

ally or in group ((see Figure 2(c)). The moderator can

access all the personas created by the participants (see

Figure 2(d)). The tool is available at the link

1

.

4 EXPERIMENTAL STUDY

Our study was conducted following the recommenda-

tion of Wohlin et al. (2012) . Our study was approved

by the Federal University of S

˜

ao Carlos ethical com-

mittee (CAAE process: 37663220.5.0000.5504).

4.1 Planning

Participants were invited to take part in the study vol-

untarily via our professional network. Our research

group has conducted different investigations about

UX in industrial settings, which established contacts

with software professionals. The participants were se-

lected by convenience, according to their availability

to participate in the study (Wohlin et al., 2012). Both

developers from startups and established companies

were invited. The participants were divided into two

distinct groups, i.e., one with software startup profes-

sionals and another composed of software profession-

als from established companies.

Personas elaboration is tightly associated with the

domain of the product; we first determined the soft-

ware focus in our study. We defined tourism mo-

bile apps as the domain of our study, being TripAd-

visor

2

and Google Maps

3

examples of these type of

apps. The tourism app was chosen because it rep-

resents a common-sense domain. Consequently, the

participants could concentrate their efforts on creat-

ing the personas artifacts, avoiding the need of learn-

ing about the app domain. Considering the app do-

main, we prepared the lean persona tool to support

our study. We kept the demographic questions (i.e.,

Q1 quadrant) suggest by the lean persona tool and de-

fined the quadrants guideline questions for the other

quadrants (see Table 1).

An online questionnaire was elaborated to gather

professionals’ profile data (e.g., years of experience,

company market segment, position in the company,

experience with tourism apps, and knowledge on per-

sonas techniques). The questionnaire included the

1

http://uxtools.uxleris.net/

2

https://www.tripadvisor.com.br/

3

https://www.google.com/maps/

Informed Consent Form to collect the participants

agreement in taking part in the study. We also cre-

ated an online feedback questionnaire based on the

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989)

to collect the participants’ perceptions about the use

of lean persona technique. TAM questions are divided

into two dimensions The perceived usefulness dimen-

sion represents how much a person considers that the

use of a specific technology may improve their per-

formance. The ease-of-use dimension is related to

the perception that technology can be adopted with

no effort. We added three open questions about the

suitability of the lean persona on the creation of the

artifacts in the feedback questionnaire.

Finally, we wrote up a scenario of users’ interac-

tion with the tourism app domain. This scenario in-

tended to overview this kind of app to support the par-

ticipants during the personas elaboration. However,

the participants were free to use all their knowledge

about this kind of apps.The scenario is described as

follow: “A tourist usually uses a mobile application

(mobile, tablet, etc.) to plan and guide their trips. The

app displays places in a city or region according to

the interest and searches made by users. These places

can be hotels, monuments, museums, parks, restau-

rants, among others. For each location, the apps

show details such as the location name, photos, ad-

dresses, and feedback from other individuals that of-

ten is ranked by a score from 0 to 5. Moreover, these

apps can present estimates of expenses to spend in the

places and also comments to assist the user to decide

and plan visits to places that have good ratings”.

A senior expert with 10+ years of experience in

UX area evaluated our study reviewing and refining

the profile questionnaire and the other artifacts. Be-

sides, a pilot test was carried out in our research group

with five UX researchers and we concluded that no

changes were necessary and the study could be run.

Table 1: Guideline questions for the quadrants Q2 to Q4.

Quadrant Guideline questions

Q2

(GQ1) What does he/she want to achieve?

(GQ2) What does he/she need to accomplish his/her goal?

Q3

(GQ3) What does he/she like?

(GQ4) What is he/she outstanding to do?

(GQ5) How does he/she like to do it?

Q4

(GQ6) What are the difficulties he/she has?

(GQ7) What barriers/obstacle can he/she face in a

task/an interaction?

(GQ8) What can disappoint him/her?

4.2 Execution

The study was conducted with 21 software profes-

sionals

4

who work in different companies in Brazil,

4

Professionals in software development positions as

such as developers, interface designers

Using Lean Personas to the Description of UX-related Requirements: A Study with Software Startup Professionals

215

being 10 professionals from software startups and 11

from established companies. In our previous contact

with the participants, we observed that most had little

knowledge about the personas techniques. To level off

the participants’ knowledge, we recommended they

watch two videos about persona and lean persona be-

fore their participation in the study.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the study took

place in online meetings using the Google Meet tool

5

.

To attend to the different schedule availability of the

participants, we ran 6 sessions distributed on different

days and each one lasted about 1 hour and a half. In

each session, we had the participation of 2 to 4 pro-

fessionals. Each participant took part in only one ses-

sion. A researcher with 1+ year of experience in UX

was responsible for running the study. In all sessions,

the same script was followed, thus avoiding the inser-

tion of biases in the study conduction.

At the beginning of each session, the researcher

welcomed participants and briefly pointed out the

study’s objective. The participants accepted the term

of consent to data and images for academic ends and

thus completed the profile questionnaire. Before start-

ing the construction of the lean personas, the partic-

ipants took part in a warm-up session where the re-

searcher presented a quick review covering the per-

sonas and lean personas concepts (i.e., based on the

videos watched by the participants previously). The

researcher thus carried out hands-on training using

the lean persona tool to familiarize participants with

its resources. After the hands-on training, the partic-

ipants built the lean personas considering the tourism

app scenario. They were oriented to create at least one

and up to three personas due to the limitations of the

study time slot. In the end, 21 participants produced

24 personas in total. The participants answered the

feedback questionnaire (i.e., TAM questions) at the

end of the study.

4.3 Analysis

We examined the 24 lean personas produced by the

participants and the answers from the feedback ques-

tionnaire. We carried out a qualitative analysis on the

learn personas artifacts to examine the presence of the

different types of UX-related requirements. We ex-

plored the Q2, Q3, and Q4 quadrants to search for ev-

idence of UX descriptions. These three quadrants pro-

vide descriptions about goals and needs, behavior and

preferences, and difficulties, respectively. In our anal-

ysis, We did not consider the Q1 quadrant because

it only informed personas demographic data and we

were interested in the requirements’ descriptions.

5

https://meet.google.com/

Figure 3: Example of labeling of lean personas artifact -

why in red and delimitated with circles; what in green and

delimitated with squares; how in purple and delimitated

with triangles.

Our analysis on the lean personas was carried out

in three steps. First, one junior researcher (i.e., 1+

year of experience) explored all the lean personas by

applying a closed coding technique (Corbin, 1998).

Closed coding guides researchers in identifying ex-

cerpts of text and labeling them to pre-established

codes which belong to a codebook (Corbin, 1998).

In our study, the codebook was composed of the UX

levels proposed by Hassenzahl (2018), i.e., the codes

“why”, “what” and “how”. The respective definitions

that each code carries guided the junior researcher to

look for evidence about UX specifications that were

presented in the learn personas. Figure 3 illustrates

our labeling activity in a lean persona that was pro-

duced by a startup professional. A senior UX re-

searcher revised and refined all the labels assigned to

the 24 lean personas as a second step. After, the two

researchers worked together to map all the labeling

(“why”, “what” and “how”) to the guideline questions

(see Table 1). Consequently, we could see the rela-

tionship between the labeling and the lean personas

quadrants. Finally, we explored the participants’ re-

sponses regarding the acceptance of the lean personas

technique. We also examined whether the partici-

pants’ profiles had influenced the technique accep-

tance.

4.4 Threats to Validity

We followed the recommendations of Wohlin et al.

(2012) to discuss the four threats to validity (i.e., con-

clusion, construct, internal, and external) and how we

proceeded to mitigate them.

We use different data sources to give reliability to

our conclusions from the results. The adoption of UX

levels and their definitions to explore the lean per-

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

216

sonas avoided the possible bias that could be intro-

duced by the researchers on the qualitative analysis.

Moreover, the closed coding process was conducted

in three steps with the participation of two different

researchers. All the codes assigned to the learn per-

sonas have been revised by researchers with experi-

ence in qualitative analysis. We also examined the

feedback questionnaire to give conclusions about our

study. To mitigate construct problems, we followed

the same script to conduct the study sessions. We used

the same artifacts (i.e., the lean persona tool and the

tourism app scenario) with all the participants to sup-

port the construction of the lean personas. We also

conducted a warm-up session providing the concepts

about lean personas to the participants. A hands-on

exercise helped the participants to handle the lean

persona tool. These two activities allowed us to miti-

gate the impact of little knowledge of the participants

about personas. The lean persona tool is fully adher-

ent to the proposed use of the template and the guid-

ing questions for building lean personas.

To mitigate the participants’ fatigue, an internal

validity threat, we conducted short sessions that lasted

no more than 1 hour and a half. By using the lean

persona tool, the participants employed less effort in

handling different artifacts during the creation of the

personas. All the information to carry out the activity

was available in the tool, i.e., the lean persona tem-

plate and the guideline questions to fulfill the quad-

rants. Concerning the external validity, the partic-

ipants who took part in the study had positions in

startups and established companies which led us to

consider we had a representative sample to our study

goals.

5 FINDINGS

We present our findings in four sections: the partici-

pants’ profile, the answers to the RQ1 and RQ2 (see

in Section 1), the influence of the participants profile

in our results.

5.1 Participants’ Profile

Table 2 presents an overview of the participants’ pro-

file. The profile questionnaire answers reveal that

from 10 participants of startups, half of them had <

1 year of professional experience and only one had

4-6 years. Considering the personas and lean per-

sonas techniques, we see that more than half had only

theoretical knowledge or never heard about the tech-

niques. We also notice that the more experienced pro-

fessional, i.e. 4-6 years, reported having only theo-

retical knowledge about these techniques. Looking

at the established company participants’ information,

we notice that 7 from 11 had theoretical and practical

knowledge about the personas technique; however, a

smaller number of participants had the same knowl-

edge about the lean personas. All the participants, i.e.

from startups and established companies, have used

some kind of tourism app which represents that they

had knowledge of the domain as end-users.

5.2 RQ1 - Type of UX-related

Requirements

To answer RQ1 (What type of UX-related require-

ments do software startup professionals describe by

using lean personas technique?), we examined the 24

personas produced by the 21 participants. We looked

for evidence of descriptions related to the three lev-

els of the Hassenzahl model, i.e., “why”, “what” and

“how” (see Figure 3). We did two granularity levels

of mapping, one more general at the level of lean per-

sonas quadrants and another more specific at the level

of guideline questions (see Table 1).

Figure 4 shows a heat-map chart with the distri-

bution of occurrences of the three levels of the Has-

senzahl’s model (see Figure 1) by the lean personas

quadrants. The results show a concentration on the

level “what” in the three quadrants (see Figure 4 (b))

in which product features are described. In Figure 4

(b), we see this results independently of the partici-

pants were professionals from startups or established

companies. From the level “why” (see Figure 4 (a)),

we observe that startup professionals did not give de-

tails on the end-users difficulties (i.e., Q4 quadrant).

The occurrences in Q4 are low even for established

company’ professionals. The results also demonstrate

that the level “how” (see Figure 4 (c)) has the lowest

number of occurrences independently of the quadrant.

By exploring the relationship between the descrip-

tions available in all quadrants, we notice that Q2

presents the most information. It predominantly de-

scribes more abstract UX-related requirements which

report why and what the users need to achieve their

objective. Q3 provides descriptions of “how” (i.e., be-

havior) to do related to “why” (i.e., preferences). In

Q4, UX-related requirements appear describing prod-

uct functionalities (i.e.,“what”) in a high level of ab-

straction to provide information on how to mitigate

the difficulties that the user could have. The descrip-

tions concretely explain “how” the interaction should

occur to minimize issues regarding the use of the soft-

ware.

We also examined the descriptions in relation to

the guideline questions per participants’ group, i.e.,

Using Lean Personas to the Description of UX-related Requirements: A Study with Software Startup Professionals

217

Table 2: Participants profile - Knowledge about the techniques is classified as (1) I’ve never heard of; (2) I only have

theoretical knowledge; (3) I used it a few times; (4) I used it a many times.

(a) Identification (b) Domain

(c) Knowledge

about the techniques

ID Group

Company

market-segment

Position

Professional

Experience

Tourism

apps often used

Personas Lean Persona

P1 Established Company Software Factory Product Owner 8+ years

Google Maps, TripAdvisor

and Youtube

2 2

P2 Established Company Finances UX Research 4-6 years Google Maps and Youtube 3 2

P3 Established Company R&D IT Analyst < 1 year Youtube 3 4

P4 Established Company Education IT Analyst 8+ years Google Maps and Youtube 1 1

P5 Established Company Financial Institution

Software

Engineer

8+ years TripAdvisor and Youtube 3 1

P6 Established Company Electronics Assembler IT Analyst 6-8 years Google Maps and Youtube 2 2

P7 Established Company Software Factory

Full-stack

Developer

1-3 years Google Maps and Youtube 3 3

P8 Established Company Software Factory Internship < 1 year Google Maps and Youtube 3 3

P9 Established Company IT IT Analyst 1-3 years Google Maps 3 3

P10 Established Company Software Factory Internship < 1 year Google Maps 3 3

P11 Established Company Health

Software

Engineer

8+ years

Google Maps, TripAdvisor

and Youtube

2 2

P12 Startup Web Development Internship < 1 year Google Maps 2 3

P13 Startup Education

Software

Engineer

1-3 years Google Maps and Youtube 1 1

P14 Startup Software House

Front-end

Developer

1-3 years Google Maps 1 1

P15 Startup

Mobile Device

Management

Back-end

Developer

< 1 year Google Maps 4 4

P16 Startup

3D Solutions

for real estate

Developer 4-6 years Google Maps and Youtube 3 2

P17 Startup Process Mining IT Analyst 1-3 years Google Maps and Youtube 4 4

P18 Startup IT Consulting Developer < 1 year Google Maps 1 1

P19 Startup Software Factory Internship < 1 year Google Maps 2 2

P20 Startup Software Factory Developer 1-3 years Google Maps 3 3

P21 Startup Shop Streaming

Front-end

Developer

< 1 year Google Maps and TripAdvisor 2 2

Figure 4: UX-related requirement occurrences mapped by quadrants and Hassenzahl’s levels - (Q2) objectives and needs;

(Q3) behavior and preferences; (Q4) difficulties.

startups and established companies. However, we saw

that the difference in the number of occurrences in

each group for each level (i.e., “why”, “what” and

“how”) has no impact on our results. Figure 5 presents

a Sankey diagram which lists the influence of the

guideline questions on the results. Sankey diagram

is a flow diagram in which the width of the arrows is

shown proportionally to the flow quantity. It helps

locate dominant contributions to an overall flow

6

.

We can see the type of UX-related requirements (i.e.,

based on UX levels) versus the guideline questions.

Figure 5 reflects a greater concentration on the use

of guideline questions to describe UX-related require-

ments of the “what” level regardless of the quadrant.

Examples of descriptions found out in the results re-

ferring to this level are: “Need to find reviews, infor-

mation, prices, and locations of places” (referring to

question GQ2), and “[...] the lack of filtering for per-

forming searches” (referring to question GQ8). This

result confirms what had already been evidenced by

6

https://www.r-graph-gallery.com/sankey-

diagram.html

the heat-map chart (see Figure 4). Specifically, we see

that guideline questions GQ1 and GQ3 of the quad-

rants Q2 and Q3, respectively, like the ones that most

guided the participants in describing the “why”. In

GQ1, we found out answers as for instance: “Plan

and guide your [the persona] next trip with friends to

an ecological city”; while in GQ3, we also found out

description to explain the “why”, for example: “Driv-

ing on beautiful roads with many landscapes”. Fi-

nally, questions GQ6, GQ7, and GQ8 (Q4) were the

ones that were most linked to “how” level, in which

we found descriptions as the following “”[...]there is

limitation of characters to the post my contributions”.

5.3 RQ2 - Feedback about the Use of

Lean Persona

Taking into account the responses collected from the

online questionnaire, we could answer the RQ2 (What

are the participants’ feedback about the use of lean

personas technique?). We analyzed the participants’

feedback regarding the perceived usefulness and ease-

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

218

Figure 5: Relation of the guideline questions and the type

of UX-related requirements.

of-use of the lean persona technique (see Table 3).

We used a four-point Likert scale as answer options,

ranging from strongly disagree to totally agree. Fig-

ures 6 and 7 illustrate the results of the acceptance

feedback for the two groups, i.e., startups profession-

als and established companies professionals. We see

that the lean persona had a good acceptance for both

groups. In particular, P4 and P14 assigned low ratings

of acceptance in most of the answers regarding easy

of use perception. These participants were from es-

tablished company and startup, respectively (see Ta-

ble 2). Looking at their profiles in Table 2, we notice

that both declared to “have never heard about the per-

sona and lean persona techniques” which can explain

their ratings. However, P4 and P14 did not give any

suggestion of improvements to technique.

We also considered the comments added by the

participants in the three open question of the ques-

tionnaire. We asked to the participants to give a justi-

fication for their point of view. First, the participants

answered about the support of the guideline ques-

tions to the lean persona construction. Most of the

participants reported that the questions cover the im-

portant points to the lean personas construction; they

also mentioned the lean characteristics that the tem-

plate carries as a positive feedback. Unlike, four par-

ticipants, P7, P9, P14 and P15 reported they wanted

to have other questions options to built the lean per-

sonas with more details. Looking at to their profile

(see Table 2), we see that they all have practical expe-

rience with personas techniques which explain their

demands of having space for giving more detail about

the persona.

The next two questions asked whether questions

should be added or removed from the template. The

most of suggestions for addition of new questions

came from the established company participants. In

general, they mentioned that questions about the

product brand, more details on the product features,

technologies that the personas have expertise, could

become the lean persona description more complete.

P2 mentioned the wish of having a space on the tem-

plate to add “[...]a statement that represents the per-

Figure 6: Startup professionals’ feedback.

Figure 7: Established company professionals’ feedback.

sona to provide more empathy to it”; P2’s answer

could be explained by the fact that s/he had more

knowledge on persona in which is usual to provide

a statement about the persona (see Table 2). For the

question of removing guideline questions, we see that

the most of suggestions were given by startups’ par-

ticipants. We observed that the quadrant Q3 was cited

by 3 participants from startups. Some the comments

are: “I think the quadrant Q3 makes me to be lit-

tle confused about the first and third questions (P15)

and “[...] when I was filling the quadrant Q3, I have

the impression that 2 questions have the same goal

(P11)”.

Table 3: Feedback questionnaire based on TAM (Davis,

1989).

Dimension ID Question

Perceived

of

Usefulness

U1 I find lean persona useful for supporting the identification of

UX-related requirements.

U2 Using the lean persona technique allowed me to achieve the

result I want.

U3 Using lean personas technique supported me for quickly

specifying details about end-users.

U4 Using lean personas technique allowed me to write charac-

teristics of representative end-users.

U5 Using lean personas technique made me to getting better in

describing end-users’ characteristics.

Perceived

of

Ease-of-use

F1 It was easy to learn how to use the lean persona technique.

F2 I find the lean persona technique easy to remember.

F3 I find it easy to understand the quadrant goals.

F4 I could use the lean persona technique as I want.

F5 It was it easy to get ability to use the lean persona technique.

Using Lean Personas to the Description of UX-related Requirements: A Study with Software Startup Professionals

219

5.4 Influence of Professional’ Profile in

the Acceptance

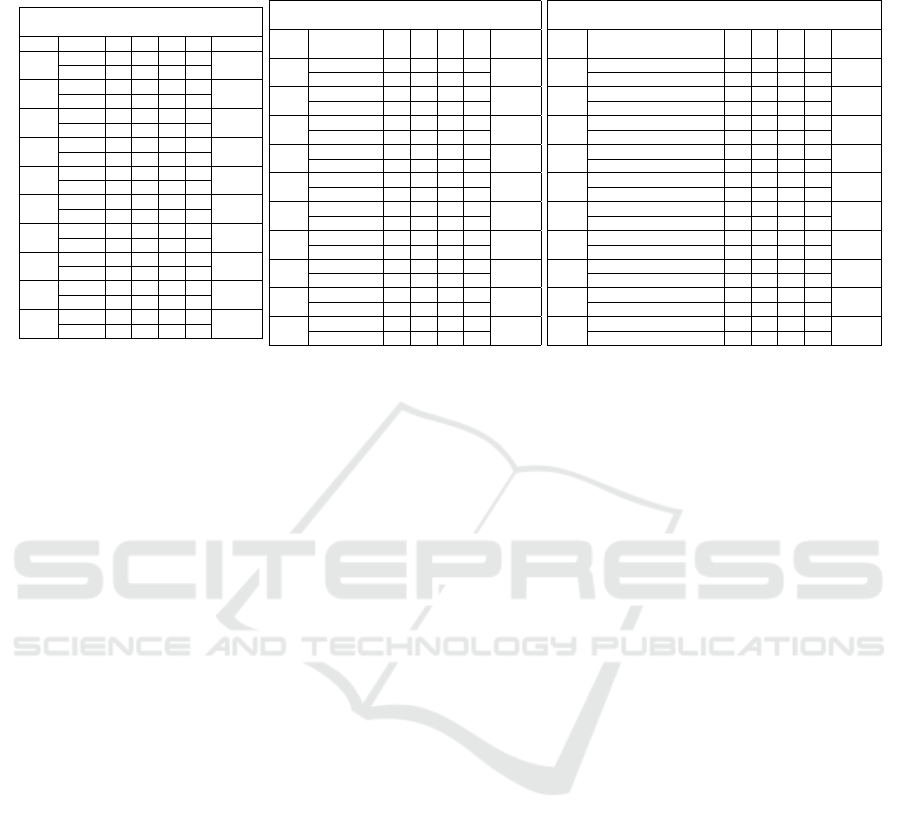

We decided to run the Fisher’s exact test

7

to check

whether the participants’ profile could have influence

on the acceptance of the lean persona technique. We

took the Fisher’s exact test because it allows com-

paring categorical data collected from small samples.

It calculates the exact significance of the deviation

from a null hypothesis using the p-value, while other

methods use an approximation. In addition to provid-

ing a p-value with greater accuracy in small samples,

the exact significance tests do not require a balanced

or well-distributed sample (Mehta and Patel, 1996)

which matches our sample’s characteristics. A 95%

(i.e., 0.05) confidence interval was considered to mit-

igate errors in the results

8

. We compiled the data for

running three different Fisher exact’s testing which

are available in Table 4 (a), (b) and (c).

First, we checked whether the company type af-

fected the acceptance results (see data in Table 4 (a)).

We thus defined the null and alternative hypothesis,

taking into account the answers of all TAM’s ques-

tions (see Table 3), as follows: H0 - The company

type where the participant work has no influence in

the acceptance, and H1 - The company type where

the participant work has influence in the acceptance.

After running the test, we got the results available in

column p-value in Table 4 (a). The results suggest

that there is no statistical evidence to support that the

fact of working in startups or established companies

influence on the acceptance of the lean personas use.

On our second testing, we defined the null and

alternative hypotheses as follow: H0 - The previous

knowledge of the participant on the Gothelf ’s lean

persona technique has no influence in the acceptance,

and H1 - he previous knowledge of the participant

on the Gothelf’s lean persona technique has influence

in the acceptance. Prior knowledge of the technique

was as “yes” for those participants that declared to

have already used the technique. We collected this

data in the profile questionnaire from the question

“Have you ever know the lean persona technique be-

fore this study?”. Table 4 (b) supported our testings

from which we see that all the p-values indicate that

there is no statistical evidence of influencing of the

previous knowledge on the technique upon the accep-

tance.

Finally, we carried out another testing to see

whether the professional’s experience could impact

on the acceptance. We used the data displayed in Ta-

7

https://www.statstest.com/fischers-exact-test/

8

We run tests from this website https://astatsa.com/

FisherTest/

ble 4 (c). The null and alternative hypotheses were de-

fined as follows: H0 - The years of professional’s ex-

perience have any influence on the technique accep-

tance, and H1 - The years of professional’s experience

have influence on the technique acceptance. We ob-

tained the results of the p-values available in Table 4

(c) which lead the rejection of null hypotheses. The

results suggest that there is no statistical evidence that

professional’s experience affect the acceptance on the

lean personas technique.

6 DISCUSSION

Taking into account our RQ1 (What type of UX-

related requirements do software startup profession-

als describe by using lean personas technique?), the

results reveal that the lean persona technique moti-

vated the participants of the two groups, i.e., startup

and established company professionals, to the writ-

ing up of UX-related requirements which cover all

the UX levels, i.e. “why”, “what”, and “how” (see

the results in Section 5.2). Looking at Figure 4, we

see a similar distribution in the four quadrants of the

lean personas considering the levels of UX. In our un-

derstanding, the use of the lean personas technique

can stimulate the professionals to describe end-users

needs even in cases where the professionals have little

experience and little knowledge in the personas tech-

nique, which are common in startups.

Our results also showed evidence that the guide-

line questions encourage the participants in describ-

ing “why” the user has a given need in different quad-

rants (see Figure 4). According to Hassenzahl (2018),

the discussion about the reasons for transforming a

set of needs into requirements is essential for the soft-

ware developers to have better insights about the soft-

ware solutions. This conversation can also lead the

software teams to be more conscious in conceiving

features that bring value to the audience (i.e., “wellbe-

ing” level of the Hassenzahl’s model - see Figure 1).

The delivery of valuable products is even more vital in

a startups environment where the professionals need

to quickly react to new target audience demands in

a highly competitive market (Hokkanen et al., 2016;

Paternoster et al., 2014). Therefore, we conclude that

lean persona can be a helpful technique to support the

low experienced software startup professionals on the

UX-related requirements specification.

Our results showed a positive acceptance of the

technique, i.e., the answer of our RQ2 ( What are the

participants’ feedback about the use of lean personas

technique?). Regardless of the group, i.e., profession-

als from startups or established companies, the partic-

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

220

Table 4: Results of Fisher exact’s test - (1) Strongly disagree; (2) Partially disagree; (3) Partially agree; (4) Totally agree;—

Group: (G1) Startup; (G2) Established Company.

Influence

of the type of company (a)

TAM Group (1) (2) (3) (4) p-value

U1

G1 0 0 3 7

0.387

G2 0 0 6 5

U2

G1 0 1 6 3

0.659

G2 0 0 6 5

U3

G1 0 0 1 9

0.098

G2 0 1 5 5

U4

G1 0 1 4 5

0.380

G2 0 2 1 8

U5

G1 0 0 4 6

0.362

G2 0 0 2 9

F1

G1 0 1 2 7

0.183

G2 0 0 6 5

F2

G1 0 1 5 4

0.505

G2 0 0 4 7

F3

G1 1 2 4 3

0.524

G2 0 3 2 6

F4

G1 0 1 4 5

1.000

G2 0 2 4 5

F5

G1 0 0 4 6

0.565

G2 0 2 4 5

Influence of

the professionals experience (b)

TAM

Professional

experience

(1) (2) (3) (4) p-value

U1

3+ years 0 0 3 4

1.000

<=3 years 0 0 6 8

U2

3+ years 0 0 4 3

1.000

<=3 years 0 1 8 5

U3

3+ years 0 0 3 4

0.742

<=3 years 0 1 3 10

U4

3+ years 0 1 1 5

0.816

<=3 years 0 2 4 8

U5

3+ years 0 0 1 6

0.613

<=3 years 0 0 5 9

F1

3+ years 0 0 3 4

1.000

<=3 years 0 1 5 8

F2

3+ years 0 0 3 4

1.000

<=3 years 0 1 6 7

F3

3+ years 0 3 0 4

0.117

<=3 years 1 2 6 5

F4

3+ years 0 1 2 4

0.827

<=3 years 0 2 6 6

F5

3+ years 0 2 1 4

0.058

<=3 years 0 0 7 7

Influence of the knowledge

on lean personas technique (c)

TAM

Knowledge

on personas techniques?

(1) (2) (3) (4) p-value

U1

Yes 0 0 2 7

0.184

No 0 0 7 5

U2

Yes 0 0 4 5

0.367

No 0 1 8 3

U3

Yes 0 0 1 8

0.159

No 0 1 5 6

U4

Yes 0 0 3 6

0.314

No 0 3 2 7

U5

Yes 0 0 2 7

0.659

No 0 0 4 8

F1

Yes 0 0 4 5

1.000

No 0 1 4 7

F2

Yes 0 0 3 6

0.519

No 0 1 6 5

F3

Yes 0 3 2 4

0.914

No 1 2 4 5

F4

Yes 0 0 4 5

0.360

No 0 3 4 5

F5

Yes 0 0 3 6

0.557

No 0 2 5 5

ipants considered the technique easy to use and use-

fulness to writing UX-related requirements (see Sec-

tion 5.3). Billestrup et al. (2014) had pointed out

that software professionals had difficulties in using

the personas technique. Our study restates the results

of Pinheiro et al. (2019) about the positive acceptance

of the lean persona technique. Our positive results can

be influenced by the guideline questions, which aided

the participants to keep the focus on describing help-

ful information on the target audience. Ferreira et al.

(2017) and Pinheiro et al. (2019) had already high-

lighted that the guideline questions support develop-

ers in a better use of the personas technique.

Nonetheless, our findings allowed us to identify

problems with the guideline questions in the Q3 quad-

rant (Behavior and preferences - see Table 1). We

conclude that we need to sift through these questions

to thus decide about their changes. Considering dif-

ferent profile characteristics, we did different Fisher

exact testings to see the influence of the profile par-

ticipants in the acceptance results (see the results in

Section 5.4). We noticed that the participants’ char-

acteristics did not have an impact on the acceptance

of the lean persona technique.

Based on the related work (see Section 2.2), we

see that our study presents important contributions

discussing the use of the lean personas technique to

support the startup professionals in the writing of UX-

related requirements. As far as we know, no other

work had carried out a similar investigation. We can

state that the works of Pinheiro et al. (2019) and Fer-

reira et al. (2017) are the closest to ours. Pinheiro

et al. (2019) had different purposes in their research:

to assess whether non-technical stakeholders, i.e., do-

main experts, could write UX requirements using the

lean persona technique, they called Proto-Personas+.

The study conducted by Ferreira et al. (2017) ver-

ified the writing of requirements in general without

the focus on UX requirements. Although Pinheiro et

al. (2019) looked at UX requirements, they did not

examine them through theoretical lenses of the UX

models proposed by Hassenzahl (2018) .

Our results show evidence about the type of UX-

related requirement that the technique encourages

participants to write up. Besides, our findings can

provide insights for future improvements on the qual-

ity of UX-related requirements specification. More-

over, software professionals took part in our study,

which differed from the studies of Pinheiro et al.

(2019) and Ferreira et al. (2017) that carried out eval-

uations with students.

7 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we investigated with 21 software pro-

fessionals the support of lean persona technique in

describing UX-related requirements. We developed a

web tool to make the creation of lean persona artifacts

easier and more automated. The results showed that

our lean persona proposal aided both groups of pro-

fessionals, i.e., software startups and established com-

panies, to focus on writing up end-user needs in dif-

ferent levels of abstraction. The needs described de-

scriptions of features, ways to interact with the prod-

uct, and the reasons for those specifications existed.

Finally, the professionals of both groups showed pos-

itive perceptions regarding the ease of use and useful-

ness of the lean persona technique.

As contributions our study presents evidence that

the lean personas technique can help professionals

Using Lean Personas to the Description of UX-related Requirements: A Study with Software Startup Professionals

221

who have little experience in describing UX-related

requirements, which are commonly found in software

startups. The use of slim and easy-to-learn techniques

is suitable to the low-resource and fast-paced environ-

ment of startups. We also contributed by developing

the web lean persona tool which automated the pro-

cess of persona construction. As future work, we in-

tend to conduct case studies in software startups set-

tings to see the usefulness of the lean persona tech-

nique in the daily work of small software teams.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the support of grant #2020/00615-9, S

˜

ao

Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). We also

National Council for Scientific and Technological

Development – CNPq, grant 313312/2019-2 and

149650/2021-3 for supporting this work.

REFERENCES

Billestrup, J., Stage, J., Bruun, A., Nielsen, L., and Nielsen,

K. S. (2014a). Creating and using personas in soft-

ware development: experiences from practice. In In-

ternational Conference on Human-Centred Software

Engineering, pages 251–258. Springer.

Billestrup, J., Stage, J., Nielsen, L., and Hansen, K. S.

(2014b). Persona usage in software development: ad-

vantages and obstacles. In The Seventh International

Conference on Advances in Computer-Human Inter-

actions, ACHI, pages 359–364. Citeseer.

Castro, J. W., Acu

˜

na, S. T., and Juristo, N. (2008). Inte-

grating the personas technique into the requirements

analysis activity. In 2008 Mexican International Con-

ference on Computer Science, pages 104–112. IEEE.

Choma, J., Zaina, L. A. M., and Beraldo, D. (2016).

Userx story: Incorporating ux aspects into user stories

elaboration. In International Conference on Human-

Computer Interaction, pages 131–140. Springer.

Corbin, A. S. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Tech-

niques and procedures for developing grounded the-

ory. volume 4, CA: Sage. Thousand Oaks.

Da Silva, T. S., Silveira, M. S., Maurer, F., and Silveira, F. F.

(2018). The evolution of agile uxd. Information and

Software Technology, 102:1–5.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of

use, and user acceptance of information technology.

MIS Q., 13(3):319–340.

Faily, S. and Lyle, J. (2013). Guidelines for integrating per-

sonas into software engineering tools. In Proceedings

of the 5th ACM SIGCHI symposium on Engineering

interactive computing systems, pages 69–74.

Ferreira, B., Santos, G., and Conte., T. (2017). Identifying

possible requirements using personas - a qualitative

study. In Proceedings of the 19th International Con-

ference on Enterprise Information Systems - Volume

2: ICEIS,, pages 64–75. INSTICC, SciTePress.

Giardino, C., Unterkalmsteiner, M., Paternoster, N.,

Gorschek, T., and Abrahamsson, P. (2014). What

do we know about software development in startups?

IEEE Software, 31(5):28–32.

Gothelf, J. (2012). Using proto-personas for executive

alignment. UX Magazine, 1.

Hassenzahl, M. (2018). The thing and i (summer of ’17

remix): From usability to enjoyment. pages 17–31.

Hokkanen, L., Kuusinen, K., and V

¨

a

¨

an

¨

anen, K. (2016).

Minimum viable user experience: A framework for

supporting product design in startups. In Sharp, H.

and Hall, T., editors, Agile Processes, in Software En-

gineering, and Extreme Programming, pages 66–78,

Cham. Springer International Publishing.

Kashfi, P., Nilsson, A., and Feldt, R. (2017). Integrat-

ing user experience practices into software develop-

ment processes: implications of the ux characteristics.

PeerJ Comput. Sci., 3:e130.

Lallemand, C., Gronier, G., and Koenig, V. (2015). User

experience: A concept without consensus? exploring

practitioners’ perspectives through an international

survey. Computers in Human Behavior, 43:35–48.

Mehta, C. and Patel, N. (1996). SPSS exact tests.

Ohashi, K., Katayama, A., Hasegawa, N., Kurihara, H., Ya-

mamoto, R., Doerr, J., and Magin, D. P. (2018). Fo-

cusing requirements elicitation by using a ux measure-

ment method. In 2018 IEEE 26th International Re-

quirements Engineering Conference (RE), pages 347–

357.

Paternoster, N., Giardino, C., Unterkalmsteiner, M.,

Gorschek, T., and Abrahamsson, P. (2014). Software

development in startup companies: A systematic map-

ping study. Information and Software Technology,

56(10):1200–1218.

Pinheiro, E., Lopes, L., Conte, T., and Zaina, L. (2019). On

the contributions of non-technical stakeholders to de-

scribing ux requirements by applying proto-persona.

Journal of Software Engineering Research and Devel-

opment, 7:8:1–8:19.

Salminen, J., Jung, S.-G., Chowdhury, S., Seng

¨

un, S., and

Jansen, B. J. (2020). Personas and analytics: a com-

parative user study of efficiency and effectiveness for

a user identification task. In Proceedings of the 2020

CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Sys-

tems, pages 1–13.

Sch

¨

on, E.-M., Winter, D., Escalona, M. J., and

Thomaschewski, J. (2017). Key challenges in agile

requirements engineering. In Baumeister, H., Lichter,

H., and Riebisch, M., editors, Agile Processes in Soft-

ware Engineering and Extreme Programming, pages

37–51, Cham. Springer International Publishing.

Sim, W. W. and Brouse, P. S. (2014). Empowering require-

ments engineering activities with personas. Procedia

Computer Science, 28:237–246.

Wohlin, C., Runeson, P., H

¨

ost, M., Ohlsson, M. C., Reg-

nell, B., and Wessl

´

en, A. (2012). Experimentation in

software engineering. Springer Science & Business

Media.

Zaina, L. A., Sharp, H., and Barroca, L. (2021). Ux in-

formation in the daily work of an agile team: A dis-

tributed cognition analysis. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies, 147:102574.

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

222