Planning and Design Challenges for Smart Infrastructures:

The Chiloé Island Case

Stefania Pareti

1a

, David Flores

2

, Loreto Rudolph

3

and Martina Pareti

4

1

Universidad Andrés Bello, Fernández Concha 700, Las Condes Santiago, Chile

2

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, El Comendador 1916, Providencia Santiago, Chile

3

Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, Avda. España 1680, Valparaíso, Chile

4

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Manuel Antonio Matta 12, Viña del Mar, Chile

Keywords: Chiloé Island Chile, Green Architecture, Small Building, Smart Infrastructures, Vernacular Architecture,

Governance Planning.

Abstract: The objective of this study is to explore how to plan and design a type of green construction along with

implementing urban governance plans, facilitating smart infrastructure and, in turn, the sustainability of the

territory. The island of Chiloé, in southern Chile, has been selected as a case study, due to: (1) it has a unique

vernacular architecture based on Smart buildings (2) it has a geographic morphology that has allowed from

its genesis as a city to build in wood and sustainable materials; (3) it is going through a transition towards

gentrification, due to its tourist attraction; (4) has a governance system.

The methodology is developed through analysis of secondary sources, regarding interviews with: key actors

of the place, together with developing a governance model adapted to the territory, finally a detailed analysis

of a stilt house is made.

It is concluded that planning and designing a type of Green construction together with implementing urban

governance plans, if it facilitates the Smart infrastructure and in turn the sustainability of the territory.

1 INTRODUCTION

The objective of this study is the exploration of

planning and design of sustainable structures as a

response to the territory. It’s argued that exploring

how to plan and design a type of green construction

together with implementing urban governance plans,

can facilitate smart infrastructures and in turn the

sustainability of the territory.

Identity expressions, uses, ideas, social and

cultural characteristics of a community are elements

that make up vernacular architecture (ICOMOS,

1999). The Chiloé archipelago, in southern Chile, is a

case study of vernacular architecture relevant in

architectural terms due to the patrimonial and

vernacular meaning of its palafittic constructions,

related to Smart buildings terms: use of local

materials and smart and functional constructions.

These are important focuses to understand how to

face the transition to gentrification through

sustainable architecture according to an urban

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0515-5389

governance system that allows managing a complex

system between cultural, social, political and

economic aspects (Paddison, 2017) that promotes the

revitalization and maintenance of heritage buildings.

The stilt houses are considered vernacular

architecture constructions due to the response they

have considering the territory: structures in border

condition that are built with a series of piles driven

with native wood, for example larch wood. They are

a conjunction between the knowledge of the tenants

with the Jesuit ideas, which arrived in the seventeenth

century, where green architecture is prioritized

without even knowing it.

The foregoing is rescued and explored, for the

analysis of the fusion between vernacular

architecture, sustainable architecture and a

contemporary governance system, translated into a

living and restored heritage in the Chiloe culture

leaving a direct relationship with the place where it is

located, as well as the ancestral construction

techniques, inherited from generation to generation.

Pareti, S., Flores, D., Rudolph, L. and Pareti, M.

Planning and Design Challenges for Smart Infrastructures: The Chiloé Island Case.

DOI: 10.5220/0011034300003203

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2022), pages 103-109

ISBN: 978-989-758-572-2; ISSN: 2184-4968

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

103

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Vernacular architecture is the characteristic

architectural form and style of a region or area, where

its architecture is defined by the knowledge and

experience of the inhabitant, in addition to the use of

local materials, which allows the realization of its

constructions. This makes it constantly evolving

looking for new ways of building. A stilt house is

understood as a type of house built on stilts, generally

made of wood, which maintains the entire house.

Most of these constructions in the world are

located in lagoons, rivers, lakes or on the edge of the

sea. The houses of Akit, vernacular houses built in

wood on stilts made by the inhabitants, respecting

nature, ecology and cultural values, being linked to

the environment and traditional (Faisal, Firzal, &

Rijal, 2019). The use of local materials such as larch

wood, together with the knowledge of the tenants, are

key to define the palafittic structures of Chiloé as

architectural heritage and an example of sustainable

architecture, where construction techniques that open

the way to functionality and architectural diversity are

evident. Cases such as Vâlcea, Sibiu and Buzău

(Bartha, 2014) where the use of local wood in homes

appears not only in the structure, but also in furniture,

reflect that the use of this material is an indicator to

classify those structures as vernacular that show

evolution in the tradition and use of raw materials.

Given the tradition of wood construction, it can

be understood that it has been an exchange of

knowledge passed down through time. Those

vernacular works can be classified into different

typologies (Maudlin, 2010; Debaillex, 2010) having

in common that they are traditional buildings

presenting a duality between the social and the

political of the time. There is little clarity regarding

the tools that are used for the constructions due to

their poor conservation, making their authenticity

difficult, so we want to combine a system of

recognition tools and reconstruct the forms of

traditional constructions, giving space to two forms,

for example recognition of typologies and also

generate hypotheses with the types of structures over

time helping a possible reconstruction.

In relation to sustainable architecture, it is a

design method which seeks to minimize the impact of

buildings on the environment, in addition to

improving life and projecting healthy spaces for the

inhabitants. There is a great urban expansion, being

compact cities those that are more sustainable but

lack green areas (Artmann, Kohler, Meinel, Gan, &

Ioja, 2019), so they propose to generate a systemic

conceptual framework, which is intended to be

defined by two focuses: the first being smart cities

responding to the needs of urban growth by giving

smart limits, and the second being green cities that

aim to conserve the environment both in its natural

environment and urban context.

Another case of green architecture is the green

infrastructure model as a mitigation measure for

environmental, social and economic sustainability

(McMahon, Benedict, & T., 2002). Where there is

conventional planning of open spaces in which it is

sought to include the conservation of the

environment. Green infrastructure must be addressed

as a strategy towards the ecological and social

impacts of open spaces, thus trying to generate a

network linked to green spaces, as well as natural

ecosystems, helping to conserve all these benefits to

the inhabitants.

Smart cities are being promoted by new

technologies (Ioanna & Dimitra, 2019), being a

means of tool to reinforce the conservation of urban

landscapes through the detection and processing of

data and influential actors, which will be

implemented to the users thus developing the

interaction of these, being a challenge to take the city

of today and that it be modified to the intelligent

practices implemented by the infrastructure giving a

new vision in the urban context. Taking into account

that landscape urbanism must be modified to

reformulate, repair and conserve the urban

environment.

The inhabitants of smart cities should be older,

since they are the ones affected in terms of

accessibility given their experience in urban design,

planning and management. In the Benalúa

neighborhood of Alicante in Spain, the members of

the neighborhood participate in providing

information and problems of their environment

(Pérez-del Hoyo, Andújar-Montoya, Mora & Gilart-

Iglesias, 2018), concluding with a network of

integration and feedback, thus generating good

communication between the administration and its

citizens, thanks to the support of new technologies.

Urban governance is defined as the structuring,

organization, together with communities and citizens,

to participate in the planning and design of the city.

"The creative city" (Healey, 2012) proposes having

innovation and creativity in its form of governance

within a proactive urban context in social and

economic boards, in addition to being focused on

culture, thus creating innovative and ingenious

activities of urban localities.

The city of Hong Kong has a governance model

where urban governance and competitiveness for the

new era of globalization are analyzed (Shen, 2004).

SMARTGREENS 2022 - 11th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

104

This indicates that it is necessary to generate changes

in urban governance for the economic, social and

environmental sustainability of each city, which must

be supported by governments and local communities

to be successful.

3 METHODOLOGY

The research is carried out through the study mainly

of secondary sources, associated with relevant actors

for the case study; architects of the area, authorities in

charge, groups or consolidated foundations or

neighborhood groups that propose a discourse

according to what was investigated.

First, the concept of governance is theoretically

developed in order to apply it to the case and generate

a governance model that adapts to the needs of the

object of study once the edges of interest have been

studied, even more so when insularity is considered

as the prevailing condition of the case. of study and

the problems of connectivity and administration that

this entails.

Secondly, Chiloé is analyzed from a general

perspective, at the urban level, based on the urban

ekistic theory of Constantinos Doxiadis (Doxiadis,

1970), mainly to understand the urban-geographical

relationship of its conformation and how from this are

taken the constructive decisions that are characteristic

of the place, understanding the constant dialogue

between the sea, the land and the seashore as the main

elements to consider when thinking about living in

Chiloé.

With this base, in the third place, we proceed to

the analysis of the vernacular architecture of the

island, closely related to the above, to finally land the

analysis on the specific object of the study, the stilt

houses, where it is studied from two perspectives, the

aspect constructive-material, and the socio-cultural-

immaterial aspect. This allows it to be related to

concepts of sustainability and from there, to

governance, in order to generate the model mentioned

in the first paragraph of this section.

4 RESULTS

Referring to governance today is not the same as

doing it 30 years ago or even more. Although the term

can easily be related to the concept of state or the idea

of a traditional government, today the concept has

been democratized. Governance does imply

government, but not just in the classic way mentioned

recently; although this is still a governance model

(Henao, 2014). This democratization has to do mainly

with the descent of the concept towards more local

and / or community organizational models, which

respond to current and particular needs of each sector,

never discarding more traditional or official

organizational models, associated with established

authorities since in this case, governance is exclusive.

Simply put, governance is the process or system by

which decisions are made, objectives are defined and

progress is made towards an objective, mainly

through cooperation. This is done at different scales

and always ascribed to the particular context of each

group that exercises governance, therefore, it is a

dynamic model (Iza, 2006).

Understanding the geographical condition of

Chiloé, an archipelago in the south of Chile where

there is more sea than land, added to the territorial

configuration and centralism of the latter, it is

possible to recognize various difficulties to configure

an efficient governance plan from high administrative

positions such as what It would be the Chilean state,

thinking about the sustainable development of Chiloé

(Montecinos, et al, 2019). Thus, the presence of local

governments, added to the work of various

organizations and communities of islanders, are key

to the configuration of a viable governance model

focused on sustainability, where the community plays

a fundamental role.

At an urban level, the Chiloé archipelago is

characterized by three primary conditions in its

geographical makeup, the sea, the land and the edge

of the sea. Beyond the obvious, the first stands out

both for its role as a limit to be overcome when

considering mobility and as a productive space, while

the second stands out from the perspective of

available land or useful space, both for living and for

producing. Within this duality, the edge of the sea

appears as a boundary strip between the two worlds,

which, despite its hardness, is diffuse thanks to the

prevailing tidal movements in Chiloé and where,

thanks to constructions such as the palafitos, a mode

of inhabit that dominates the three conditions

achieving a unique habitability that combines sea,

edge and land. The latter is a key part of the

vernacular architecture of the archipelago, which,

together with the Chiloé churches and minor elements

such as the larch wood shingle among others, are the

physical representation of a particular and rich culture

based on the cultural syncretism of Jesuits and

indigenous peoples, where there is a clearly

identifiable architectural style that takes wood as a

local imprint (Rojas, 2021).

Planning and Design Challenges for Smart Infrastructures: The Chiloé Island Case

105

Adding to the equation, ekistics as urban theory

raises the understanding of urban settlements through

different scales relating physical aspects with social

aspects (Doxiadis, 1970). Thus, he postulates that for

a human settlement to be successful, there must be a

balance in what are considered as the five ekistics

units (nature, man, shelters, society and networks).

Nature is the natural space where man is established,

who becomes an inhabitant and therefore builds a

refuge, understanding that the notion of refuge ranges

from a tent to a building. By living with others, man

forms a society where the first networks are created

based on their social relationships. The networks also

make literal reference to mobility, that is, roads and

sea or air routes that allow the transfer of man

between refuges and nature. Thus, it is enough that

one of these units is taken over for an imbalance to

begin that will eventually bring negative

consequences for the settlement.

Applying the theory to Chiloé, nature is

geographic space; sea, land and border, together with

their natural resources that, from the insularity,

become fundamental given the difficulties of

connectivity. The chilote becomes the man. He is the

one who, along with other Chilotes, build their cities

and towns across the various islands, where, given the

aforementioned cultural syncretism, they now have a

clear and defined identity based on both technical and

ideological knowledge that make them Chilotes, as

well, build society based on the consolidation of said

identity that also generates social networks. The

physical networks are all the roads along the islands,

in addition to the maritime routes that allow the

connection of the entire archipelago where travel by

sea is mandatory under certain circumstances.

This analysis seeks to establish the urban structure

of Chiloé as a self-sufficient unit in itself, with clear

and definable elements that become key variables to

propose a governance model. In this sense,

emphasizing once again how the territorial

conformation of Chile encourages centralisms that

hinder governance models from official bodies that

respond to local needs, in Chiloé as an area there are

three elements to consider when proposing a model.

These would be the geography, cultural heritage and

tourism, understood as the historical conditions of the

place (Rojas, 2021) and, therefore, maintaining the

balance between these is key for the sustainable

development of the archipelago, these three

fundamental parts of the landscape that characterizes

it.

Given the difficulty of accessing external

resources, Chiloe architecture was consolidated based

on wood. The aforementioned syncretism between

native peoples and Jesuits also gave way to a

carpentry school of its own style that ends up

configuring a clear architectural image, where it also

becomes one more element of those that make up the

identity of Chilote and its vernacular architecture.

Regarding the latter, the use of wood was not only

for its abundance, but also for its resistance to water

(specifically native woods) and thermal

characteristics, therefore, the result is an architecture

that takes charge of its environment. and climatic

characteristics with the resources it has available,

postulated today related to sustainability but that in

the case of Chiloé have been developing long before

this was even thought (Rojas, 2021).

Even so, it is important to highlight how, despite

the fact that today the use of wood is associated with

the concept of sustainability given its low carbon

footprint, the difficulty of accessing other materials

within the islands and the overexploitation of wood

did that various species were predated to the point of

almost disappearing, being considered today

protected species, an example of how, from the

ekistics, the imbalance of a unit, in this case nature,

alters an entire system. This is one of the edges to

consider when you want to establish a sustainable

governance model for the archipelago.

Within the Chilote vernacular, builder of its own

architecture but in addition to an identity and a

cultural heritage formed over years, fundamental for

the social development of the archipelago, the

palafito is presented as one of the characteristic

elements of the archipelago's imaginary together with

the scattered churches through the islands and the tile

that covers almost all the houses of Chiloé. Taking

care of the need for housing, the scarcity of land and

the relationship with the sea, the palafito is built on

the sea to also simplify the life of the fisherman who

goes directly to his boat from the porch of his house.

The relationship with its surroundings and the

proposed habitability, both related to ekistics, allow

the architectural element or object to be analyzed

from the microscale as an example of Green

architecture.

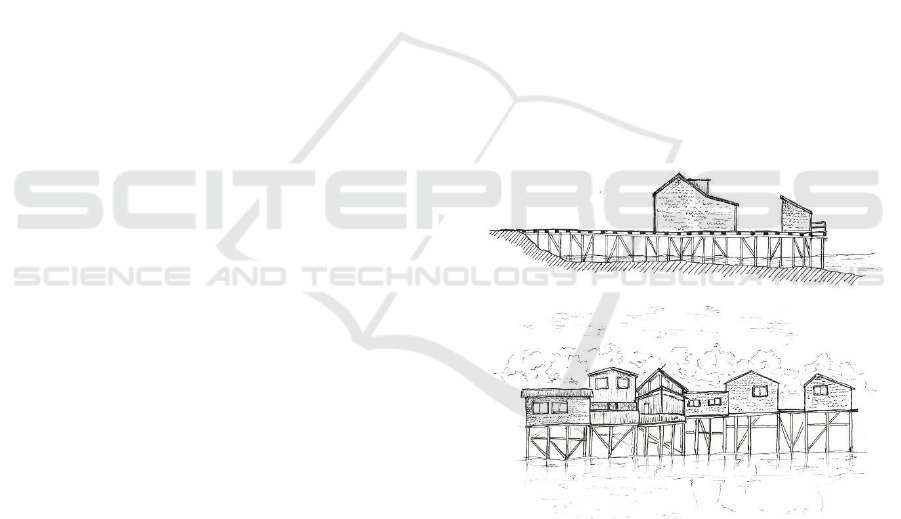

Formally, the palafito is a house that is built

suspended over the sea, supported by a series of piles

(Figure 1), which, like most of the Chiloé houses, is

configured around the stove and has a low height to

better preserve the temperature. of the predominance

of the full over the void for the same reason. It is also

characterized by being part of the phenomenon of

self-construction, like a large part of the houses in the

archipelago, and under this logic, it is also associated

with popular knowledge and knowledge in the use of

SMARTGREENS 2022 - 11th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

106

wood characteristic of Chiloé's cultural wealth

(Riveros & Tendero, 2021).

Although there was a time when the palafito was

a symbol of poverty and bad living (Rojas, 2021),

today it takes its place as an object of identity, being

a key attraction for tourism and for architectural

interventions. These, added to awareness for the

environment, which implies a regulation in the use of

native woods and technological advances that allow

the redefinition of certain traditional architectural

decisions (such as the existence of a stove, for

example) are the new precepts. to take into account if

you want to implement a governance system based on

sustainable architecture, understanding Chiloe

architecture as the materialization of a unique cultural

heritage and the realization of a way of living.

Thus, today the palafito went from being just a

home to hosting programs such as boutique hotels,

cafes and even churches, where new technologies are

also applied to redefine spaces and create a new

habitability that adapts to current needs (Ibid.).

Although this implies the redefinition of constructive

traditions and cultural aspects, the proper

performance of said operations is part of the

considerations that a governance system must have

that seeks to take advantage of tourism in the area, but

always respecting a key cultural wealth to the

understanding of Chiloé.

It is then worth asking how the stilt house as an

object reflects the needs to establish a sustainable

governance model with a Smart focus. Thus, it is

essential to think about how to develop a wooden

architecture based on the vernacular with the current

climatic and productive challenges, where the

exploitation of ancient native species is no longer

possible, which also implies that the climatic factor

that these supplied must be approached otherwise.

This also entails the consideration of new

technologies, mainly climate, as part of this new

Chiloe architecture, where their inclusion must

always be in pursuit of a specific architectural type

without the intention of transforming it into

something new, but rather adapting it to new needs;

allow progress, but always maintaining the essence of

Chiloé architecture. In addition, Chile's centralism

with respect to the administration of the territory must

be considered, where there is a historical debt with the

territories and regions (Montecinos, et al, 2019),

therefore, beyond proposing a model at the country

level, It is necessary to propose a model based on

communities, not only because of the aforementioned

problem, but because these are presented as an

opportunity for development as it is an established

system throughout the archipelago given the

condition of insularity, where the neighborhood

support networks and community are already formed

and are part of the identity of the place; Without going

any further, much of the Chiloe worldview and its

rites are based on community activities, including

festivities (Ampuero, 1952). This approach also goes

hand in hand with the promotion of popular

knowledge, and, therefore, with the transmission of a

cultural heritage thinking of future generations and

not only in its exploitation as a product by the tourist

activity. a human group, this implies both cultural and

material aspects, therefore, the correct establishment

of a governance system for Chiloé must take care of

both material wealth and immaterial wealth since

both go hand in hand for the correct understanding of

the ekistic system of the archipelago; The focus on

this object to develop the research has to see how the

immaterial culture of Chiloé falls on the material

culture, they feed back. In addition, in a place highly

demanded from a tourist perspective, such

governance must take charge of the correct

development of cultural wealth, where although it

becomes a product, it cannot lose its significance for

those who practice it, ending in a bad caricature. of an

entire identity-generating culture.

Figure 1: Stilt houses sketch. Own elaboration.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Since its beginnings in pre-Columbian times, the

inhabitants of Chiloé have developed based on their

context. This relationship takes shape in the

development of a clear and defined architectural style

always related to wood and in the domain of mobility

over a territory that can become hostile when one

thinks of moving from one island to another. Even

within all this hostility and almost precariousness that

Planning and Design Challenges for Smart Infrastructures: The Chiloé Island Case

107

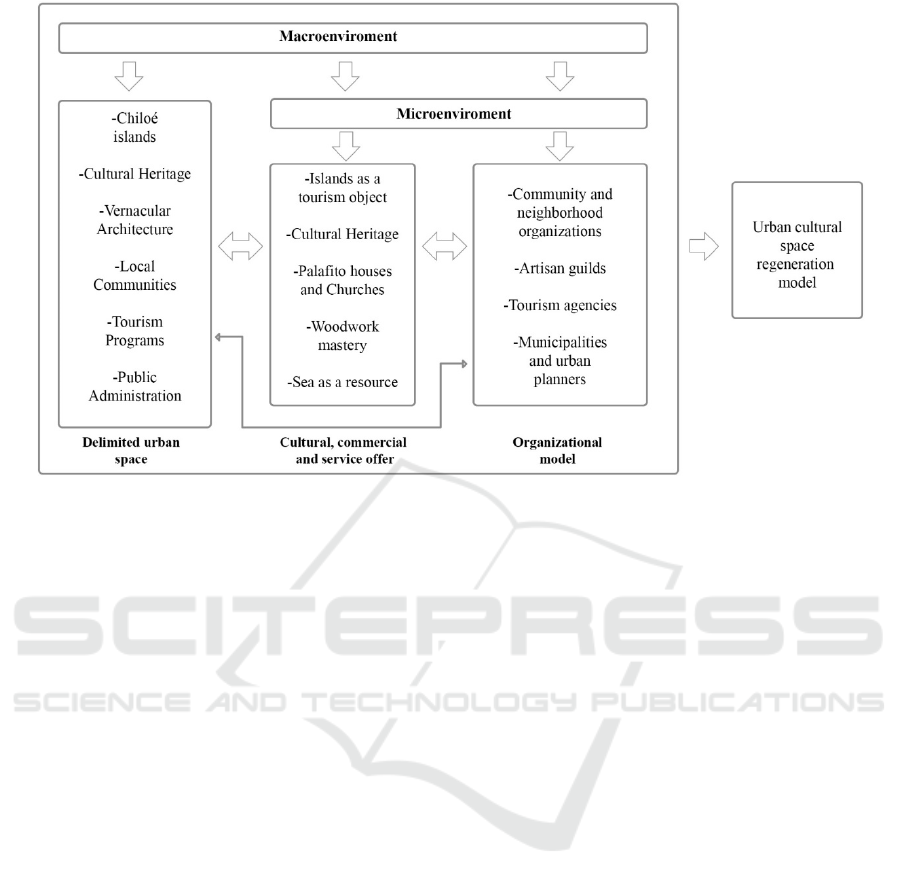

Figure 2: Schematic basis proposed for the model. Own elaboration.

can imply a degree of isolation, a particular and

efficient way of living was created with respect to

what it sought to solve, mixing all the knowledge that

being Chilote can offer. Although the result is an

architecture that can be associated with sustainability

postulates, without a regulatory framework, a correct

governance model presents imbalances that clearly

weaken its development over time. This way of

living, materialized in a particular vernacular

architecture, is presented as a palpable base of

opportunities to establish sustainable development

models capable of not only taking charge of what is

built from an economic-tourist perspective, but also

present as an opportunity to develop social elements

grouped in a cultural heritage, also understanding that

the true sustainability of a community does not

depend only on maintaining the physical, but also the

social. The consolidation of material and intangible

elements should always be a fundamental part when

thinking about green architecture, where the identity

elements generated by cultural heritage also reveal

the importance of these means of development and

governance models being through work with

communities , responding to needs and direct

problems that allow the development of these, even

more so when said communities are already

consolidated, giving a work based firm enough to

bear the burden of carrying out a particular and

culturally rich governance model, materialized in the

built elements.

Thus, the palafito stands out not only from a

formal look or as an object to observe, it stands out

for being the recipient of material and immaterial

traditions, for being an example of an architectural

style that knew and knows how to take care of its

environment and its needs, where it also gives rise to

social relations both with others and with the context,

allowing both the development of traditional

economic activities such as fishing, but also the

evolution of the building and its configuration

towards the new needs that urban development and

the arrival of the Tourism implies, not staying

stagnant in time and evolving to once again respond

to a new context that surrounds it, but always with a

solid base rooted in the Chilote cultural heritage.

Therefore, a governance model applied to the case

and designed for sustainable urban development

(Figure 2) must always, with cultural heritage as the

right foot, think about the development of an

architecture based on vernacular models, but adapted

to the needs and opportunities current issues

regarding how to respond to mainly productive and

climatic problems. It should be focused from

community development, understanding that these

groups, as the basic unit of human settlements, have

the necessary capacity to organize themselves with

respect to their needs and

from there, propose solutions that may or may not rise

up the hierarchies as necessary. In addition, they are

those who carry out and on whom fall the knowledge

and cultural richness that has been referred to so

SMARTGREENS 2022 - 11th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

108

much, therefore, empowering communities and

focusing on them means focusing on these aspects. It

must take charge of tourism, understanding it as a

necessary economic activity and if it is worked well,

beneficial, but which should not result in the

theatricalization of cultural traditions and rites.

Tourism should also be understood as one more

condition for architectural development, providing

the services and equipment necessary for its proper

development, but always within the framework of

vernacular architecture that knows how to work with

its context. And so, finally, it must take charge of its

geographical context, understanding both the sea, the

land and the edge of the sea as the palafito already

does. Understand the operation of movement

networks, as despite the fact that Chiloé is made up of

various islands, all are recognized as part of, and each

inhabitant can be identified as Chilote, and

understand how from the beginning the archipelago

knew how to develop together with its ecosystem, in

order, despite certain excesses that have already been

regulated, to be what it is today materially, socially

and culturally.

REFERENCES

Ampuero G. (1952). Repertorio folklórico de Chiloé

[Chiloé folkloric repertoire]. Anales de la Universidad

de Chile, No. 85-86 año 110, serie 4, Page 5-95.

Santiago, Chile.

Artmann, M, et al. (2019) How smart growth and green

infrastructure can mutually support each other—A

conceptual framework for compact and green cities.

Ecological Indicators, vol. 96, p. 10-22.

Bartha, B. (2014). Wood utilization patterns concerning

vernacular architecture and furniture in Vâlcea, Sibiu

and Buzău Counties. Pro Ligno, vol. 10, no 1.

Benedict, M A., et al. (2002) Green infrastructure: smart

conservation for the 21st century. Renewable resources

journal. vol. 20, no 3, p. 12- 17.

Debaillux, L. (2010) Complementary approach for

vernacular wooden frame structures reconstruction. En

Euro-Mediterranean Conference. Springer, Berlin,

Heidelberg. p. 441-449.

Doxiadis, C. (1970) C. Ekistics, the Science of Human

Settlements. In Science, vol. 170, nº 3956, pp. 393-404.

Faisal, G., Firzal, Y., & Rijal, M. (2019). “Study of

vernacular coastal architecture: the construction og

Akit's house in Rupat island”. Department of

Architecture, Universitas Riau, 449 - 451.

Gun F., Firzal Y. and Rijal M. (2019)."Study of vernacular

coastal architecture: The construction of Akit’s house

in Rupat island.".

Healey, P. (2004) Creativity and urban governance. The

Planning Review, vol. 40, no 158, p. 11-20.

Henao, R. (2014) “Gobernanza Sostenible”: Propuesta de

un modelo de gestión para la sostenibilidad del

desarrollo en la ciudad de Medellín a través de la

reinterpretación de la metodología CES (Ciudades

emergentes sostenibles) [Sustainable governance:

Proposal for a management model for the sustainability

of development in the city of Medellín through the

reinterpretation of the SEC methodology (sustainable

emerging cities)]. Revista Movimentos Sociais e

Dinâmicas Espaciais, Recife, Vol. 3. n°1

ICOMOS (1999). Carta del patrimonio vernáculo

construido [Letter of the built Vernacular Heritage].

Iza, A. (2006). Gobernanza del agua en América del Sur:

dimensión ambiental [Water governance in South

America: environmental dimension]. Gland, Suiza y

Cambridge, Reino Unido: Unión Mundial para la

Naturaleza/Ministerio Federal de Cooperación

Económica y Desarrollo (BMZ).

Ioanna, F; Dimitra, T. (2019). A Strategic Approach to

Smart Cities through CA and Shape Grammars.

McMahon, Benedict, M. A., & T., E. (2002). “Green

Infrastructure: smart conservation for the 21 st

century.” Renewable resources journal, 12-17.

Maudlin, D. (2010) Crossing boundaries: Revisiting the

thresholds of vernacular architecture. Vernacular

Architecture, vol. 41, nº 1, p. 10-14.

Montecinos, E., Neira, V., Díaz, G. Park, J. (2019)

Gobernanza democrática, descentralización y

territorio: Análisis del plan Chiloé en Chile

[Democratic governance, decentralization and territory:

Analysis of the Chiloé plan in Chile]. Andamios. Vol.

16. n°41

Paddison, B. (2017) “Advocating community integrated

destination marketing planning in heritage

destinations: the case of York” Journal of Marketing

Management, N° 33, pp. 9-10

Pérez-del Hoyo, R., Andújar-Montoya, M. D., Mora, H., &

Gilart-Iglesias, V. (2018). Citizen Participation in

Urban Planning-Management Processes. Proceedings

of the 7th International Conference on Smart Cities and

Green ICT Systems, 206-213.

Riveros, P. and Tendero, R. (2021) “Vernacular

architecture in the palafitos from Chiloé”. Building &

Management, vol. 5 (2), pp. 07-13

Rojas, E. (2021). Artifica tu casa 2021: Edward Rojas habla

sobre la arquitectura de Chiloé [Artífice your house

2021: Edward Rojas talks about Chiloé's architecture],

[Online]. Available:https://www.youtube.com/watch?

v=WY2ZLPGSCdg. [Last Access: December 16th

2021].

Shen, J. (2004) Urban competitiveness and urban

governance in the globalizing world. Asian geographer,

vol. 23, no 1-2, p. 19.

Planning and Design Challenges for Smart Infrastructures: The Chiloé Island Case

109