A SWOT Analysis of Software Technologies for Driving Museum Digital

Transformation

Christophe Ponsard

1

and Ward Desmet

2

1

CETIC Research Centre, Charleroi, Belgium

2

NAM-IP Computer Museum, Namur, Belgium

Keywords:

Museum, Digital Transformation, Pandemic, Requirements, Personas, Electronic Guide, Virtual Reality,

Accessibility.

Abstract:

Museums play a key cultural role in educating citizens through the immersive experience they provide. The

recent lockdowns have awakened them to the need to accelerate their digital transformation and to propose

new kinds of experience to their public. This paper performs a SWOT analysis considering the Strengths,

Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats from existing and emerging digital technologies w.r.t. the range of

services and missions a museum is delivering both internally as a company and externally to the society. Our

work relies on a number of technological evolutions reported in the literature and experienced in our computing

heritage museum with a strong focus on the user experience and accessibility.

1 INTRODUCTION

The main mission of a museum is to preserve cul-

tural artefacts and make them accessible for under-

standing to present and future generations. Muse-

ums achieve this goal through collecting, inventory-

ing, restoring and exhibiting artefacts of their specific

domain of expertise: art, archaeology, nature, science

or technology among many other areas of human ac-

tivities. Museums offer the public an immersive and

structured access to culture mainly through exhibi-

tions (permanent or temporary) and possibly through

specific events such as conferences and workshops

which can target a specific public (e.g. kids, schools,

seniors). Museums remains essentially ”brick-and-

mortar” spaces and as such they have to legally meet

physical accessibility requirements for their public ar-

eas with specific standards, regulations, assessments

and tools for supporting this process.

Digital transformation can be defined as the “pro-

cess through which companies converge multiple new

digital technologies, enhanced with ubiquitous con-

nectivity, with the intention of reaching superior per-

formance and sustained competitive advantage, by

transforming multiple business dimensions, includ-

ing the business model, the customer experience and

operations, and simultaneously impacting people and

networks” (Ismail et al., 2017).

Museums have started their digital transforma-

tion a while ago, understanding that it would add a

extra digital dimension complementing and not re-

placing the physical dimension, leading to the con-

cept of Post-Digital museum (Parry, 2013). However,

the pace and scope of transformation (e.g. focused

on internal workflows vs visitors) can vary widely.

By freezing physical access, the COVID-19 lock-

downs have revealed the need for developing a digi-

tal presence and have accelerated the adoption of spe-

cific digital solutions such as virtual tours, efficient

booking systems or online events (Dasgupta et al.,

2021)(Zuanni, 2020).

Observing this transformation is helping to under-

stand the nature of various technological factors that

can have positive or negative impacts on its success,

either from an internal point of view (i.e. Strengths

and Weaknesses) or external factors (i.e. Threats and

Opportunities). This results in a SWOT analysis. This

paper is focusing on software technologies driving

digital transformation.

Our paper is organised as follows. First, Section

2 details the main museum missions and impersonate

them through a set of personas enabling us to clearly

identify enablers and barriers to digital transforma-

tion. Section 3 then explores the four dimensions of

the SWOT from the point of view of various existing

and emerging digital technologies and the underlying

software artefacts. It is illustrated by several pub-

lished works and by our own experience with com-

550

Ponsard, C. and Desmet, W.

A SWOT Analysis of Software Technologies for Driving Museum Digital Transformation.

DOI: 10.5220/0011320800003266

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Software Technologies (ICSOFT 2022), pages 550-556

ISBN: 978-989-758-588-3; ISSN: 2184-2833

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

puter museums. Based on this, Section 4 discusses

how to best drive a digital transformation in a mu-

seum context. Finally, Section 5 draws some conclu-

sions and discusses future work.

2 MUSEUM MISSIONS AND

PERSONAS

2.1 Main Missions

The main missions of a museum involve different

kinds of stakeholders:

• purely internal; it is the work of the curator and

specialised staff to gather, study, restore and pre-

serve artefacts for future generations.

• interaction with other partners for exchanging ex-

pertise or artefacts.

• interaction with the public for setting up exhibi-

tions based on a carefully selected set of arte-

facts, editing brochures/books, organising guided

tours/workshops/conferences.

2.2 Key Personas

Personas are archetypal descriptions of users that em-

body their goals (Cooper, 1999). Their focus on

typical fictional business users helps in elaborating

specific user aspects that may be missed by other

approaches based on generic roles. Personas have

proven very effective with psychological evidence

about our natural and generative engagement with de-

tailed representations of people (Grudin, 2006).

A key issue is of course the selection process of

the relevant personas. The selected archetypes must

cover the broad spectrum of people with different

backgrounds/experience/roles. The selected number

should be kept minimal but ensuring the coverage

of the museum missions. Related to museums, we

can list the following interesting personas and char-

acterise them with some user stories:

• Carine, as curator, would like to have an efficient

museum inventory system in order to assess the

quality and state of the collections.

• C

´

edric, as steward, would like to have the list of

scheduled visits and workshop activities to pre-

pare them in due time.

• Gaelle, as animator, would like to publish infor-

mation on social networks and to specific targets.

• Ward, as director, would like to easily manage the

various projects and schedules involving internal

staff, external partners and/or volunteers.

• Chris, as researcher and Robert, as technician,

would like to easily retrieve artefacts and related

scientific and technical information.

• Alice, as 6 year kid, would like to enjoy a playful

experience of the museum.

• Vincent, as wheelchair visitor, would like to easily

register online, prepare his visit through a virtual

tour and consult information in an accessible way.

• John, as foreign visitor, would like to benefit from

translation in his language or in English .

3 SWOT ANALYSIS

In this section, we perform a SWOT analysis consid-

ering the four following dimensions:

• Strengths. Achievements/capabilities of current

ICT in supporting museum missions and user sto-

ries, also identifying possible evolutions.

• Weaknesses. Challenges of current ICT in sup-

porting museum missions and user stories.

• Opportunities. New possibilities enabled by ma-

turing software-based technologies, illustrated by

some early adopters.

• Threats. New barriers raised by those new tech-

nologies with a discussion on how to address

them.

3.1 Strengths

Collections Management System (CMS) is software

used by the internal staff of a museum or other col-

lecting institutions like archive centers. They are

typically used by the curator and technician roles.

Early CMS were more cataloging databases, essen-

tially digital versions of card catalogs, e.g. Filemaker

(Claris, 1985). They evolved to more advanced sys-

tems providing specific profiles for each role and also

improving communication between museum staff and

directly supporting the collections-based tasks and

workflows (Swank, 2008). They can also provide a

web interface which can be expose the collection to

the general public with a dedicated search engine. An

illustrative Open Source solution is Collective Access

(Whirl-i-Gig, 2012) depicted in Figure 1.

An area of further improvement is to connect the

CMS to other software, e.g. for an interactive guide,

using specific extraction and filtering which could

help a visitor or a researcher to see beyond what is

exposed in an exhibition.

Support for Accessibility for Mobility Im-

paired People is required in museum due to legal

constraints. Like other places open to the public,

museums have to comply with specific norms such

as (ISO, 2011). This means adequate circulation for

A SWOT Analysis of Software Technologies for Driving Museum Digital Transformation

551

Figure 1: Web interface of Collective Acces CMS.

wheelchairs, adapted height of the displays, video

subtitling, audio guides, visits in sign language, ac-

cessible toilets, etc. Methodologies to identify spe-

cific barriers are available as well as supporting in-

formation sharing platforms, e.g. (Jaccede.com, )

or (CAWAB, ) which are depicted in Figure 2 with

pictograms for specific disabilities (mobility, visual,

hearing and cognitive). Model-based digital tools are

also available to support them (Ponsard and Dari-

mont, 2017).

Figure 2: Access-i portal showing museum physical acces-

sibility.

An area of further improvement is to go beyond

the pure physical experience in order to provide more

help in the preparation phase before the visit, in-

creased digital support during the visit and possibly

extended experience after the visit. Those issues will

be elaborated in the next parts of the SWOT and are

also detailed in (Ponsard et al., 2017).

3.2 Weaknesses

We list some important weaknesses that can be used

as driver on how to provide an increased experience.

Physical Visit Can Be Limited in Many Ways.

First, using a purely traditional scenography requires

to organise the path to tell a specific story, thus with a

specific angle and selecting on what to focus as shown

in Figure 3. Details can possibly be overlooked but

will still occupy some physical space. In the case of

multilingual content in printed form, it will also in-

crease constraint on the text length. Of course exist-

ing digital media can help: for example audio/video

guides can provide different kind of tours for differ-

ent profiles and enable to choose to have more details,

but more immersive and interactive experience is usu-

ally missing.

Figure 3: Physical constraints put on a museum visit.

Areas of new experience here would be to allow

the visitor to define specific viewpoints in a controlled

way and to construct his own exploration path, for

example based on his area of interest. This process

could be dynamic and adaptive based on the way the

visitor is discovering the domain.

Lack of Online Experience. A related issue, it also

that few museums provide an experience beyond their

walls. For many museum, this resulted in a complete

loss of contact with the public during the pandemics

and triggered an awareness to address this issue. Re-

connecting with the public means providing online

experience, e.g. through social networks by triggering

interaction on specific topics, animating live sessions

and more generally maintaining a link.

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

552

3.3 Opportunities

In this section, we explore some emerging technolo-

gies and look how they can help improving the mu-

seum experience. This list is meant to be illustrative

and do not claim to be exhaustive.

Mobile Applications are actually not so new but

have become quite easy to develop including in a

cross-platform way using open source frameworks

like ReactNative (from Facebook) or Flutter (from

Google). This can provide a cheaper alternative to the

development and management of audio/video guides

as the user can install it on its own smartphone. The

link between the physical exhibition and the internal

content can be maintained using identifiers or QR-

code. The application can also include multimedia

or interactive content like a quiz or a (serious).

Figure 4: Mobile application with an interactive timeline.

Virtual Reality (VR) can be used to reproduce

the physical layout of a museum and provide a re-

mote experience. This same experience can be use-

ful to prepare or extend the physical visit, e.g. for

disabled people or to check back later for specific

aspects. For example Figure 5 shows a virtual tour

of the IN2P3 computer museum. Another scenario

is to showcase artworks in virtual spaces based on

high quality scans or photographs of physical arte-

facts. Designing a VR space providing a good user

experience is still an heavy and specialised work al-

though some Open Source solutions are emerging

such as as OpenSpace3D (I-maginer, 2020) or Marzi-

pano (Google, 2016). Another extension is to host

such spaces in the so called metaverse and being able

to access it in a more easy and standard way but this

technology is still emerging. The strong potential of

such technologies as been identified at the European

level, especially for the co-creation of value through

Digital Innovation Hubs (EDIH) (Maurer, 2021).

Augmented Reality and Avatars rely on technol-

ogy like a smartphone or smart glasses to superimpose

Figure 5: Virtual tour of the CCIN2P3 computer museum.

images, text or sounds on top of what a visitor can al-

ready see. This can be used in various ways. An ob-

vious usage is just to add explanations relating to the

viewed artefact, which can help in providing more de-

tails or multilingual content. A more artistic scenario

can be to display the digital version of an artist next to

its work and use it as an avatar providing a narration.

An avatar can also be used to welcome the visitor and

simulate a guided tour. Using chatbot technology can

also increase the experience with some limited inter-

activity. It is also possible to bring things to live, for

example putting flesh back on a dinosaur as depicted

in Figure 6 or to simulate the operation of an artefact

such as machine to see and hear it in operation even

though the real artefact is inactive (Coates, 2021).

Figure 6: Augmented reality in a science museum.

3.4 Threats

In this section, we identify some emerging threats and

how to deal with them.

Cybersecurity will become an issue as the mu-

seum is increasing it dependency on digital technolo-

A SWOT Analysis of Software Technologies for Driving Museum Digital Transformation

553

gies and online presence. This can results in threats

both on confidentiality (especially personal data), in-

tegrity (e.g. website defacing) and availability of

the provide services (e.g. reservation, virtual tour).

The impact can be damageable in many dimensions:

reputation, financial loss (missed visitors) or legal

(GDPR). This issue should be tackled by introduc-

ing a cybersecurity awareness and culture inside the

museum in a similar way as it is done inside SME.

The recommendation is to train an internal reference

person which can rely on an external expert. A risk

analysis must be performed as first step and then ade-

quate measures must be deployed and monitored.

Digital Accessibility is already present with the

web but will take increased importance with other

technologies such as apps or immersive experience.

The museum should start to comply with available

standard for website accessibility. The Web Acces-

sibility Initiative (WAI) (W3C, a) provides Web Con-

tent Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) to help Web

developers making Web sites accessible (W3C, b)

while dynamic content is addressed through ARIA

(Accessible Rich Internet Applications). Many use-

ful evaluation and repair tools exist, including those

for tailored and optimised usability and accessibil-

ity evaluation (Vanderdonckt and Beirekdar, 2005).

The emergence of augmented/virtual reality experi-

ence might require new guidelines in an area which

is still in its infancy and with incremental needs for

learning and improvements.

Maintenance and Digital Obsolescence also be-

comes an issue in a fast evolving world. In response

to this, relying on maintained and open (source) tech-

nologies is advised. It means the museum should be

able to rely on an internal resource or have a long term

relation with a close partner to help in developing and

maintaining the software solutions. This can be done

by collaborating with structures such as a fablab or a

creative hub.

Last but not least, adoption is also an important

barrier to consider regarding the success of digital

transformation. Smaller structure maybe more flex-

ible but have less resource and experience to con-

duct change. For addressing this, different tools can

be considered such as the adoption of an adequate

framework such as Training of Organizational Work-

ers such (ToOW) which has been applied for digital

transformation (Ferreira. et al., 2017). The integra-

tion into a creative hub mentioned earlier will also

bring other expertise and help to overcome barriers.

More specifically for a museum, it is also important to

drive the transformation by keeping in mind the user

experience as detailed in the next section.

4 DRIVING THE DIGITAL

TRANSFORMATION

In order to embrace a digital transformation, it is im-

portant not to focus on current physical criteria which

are bound to this dimension but also on higher level

goals. For this purpose, it is worth considering the

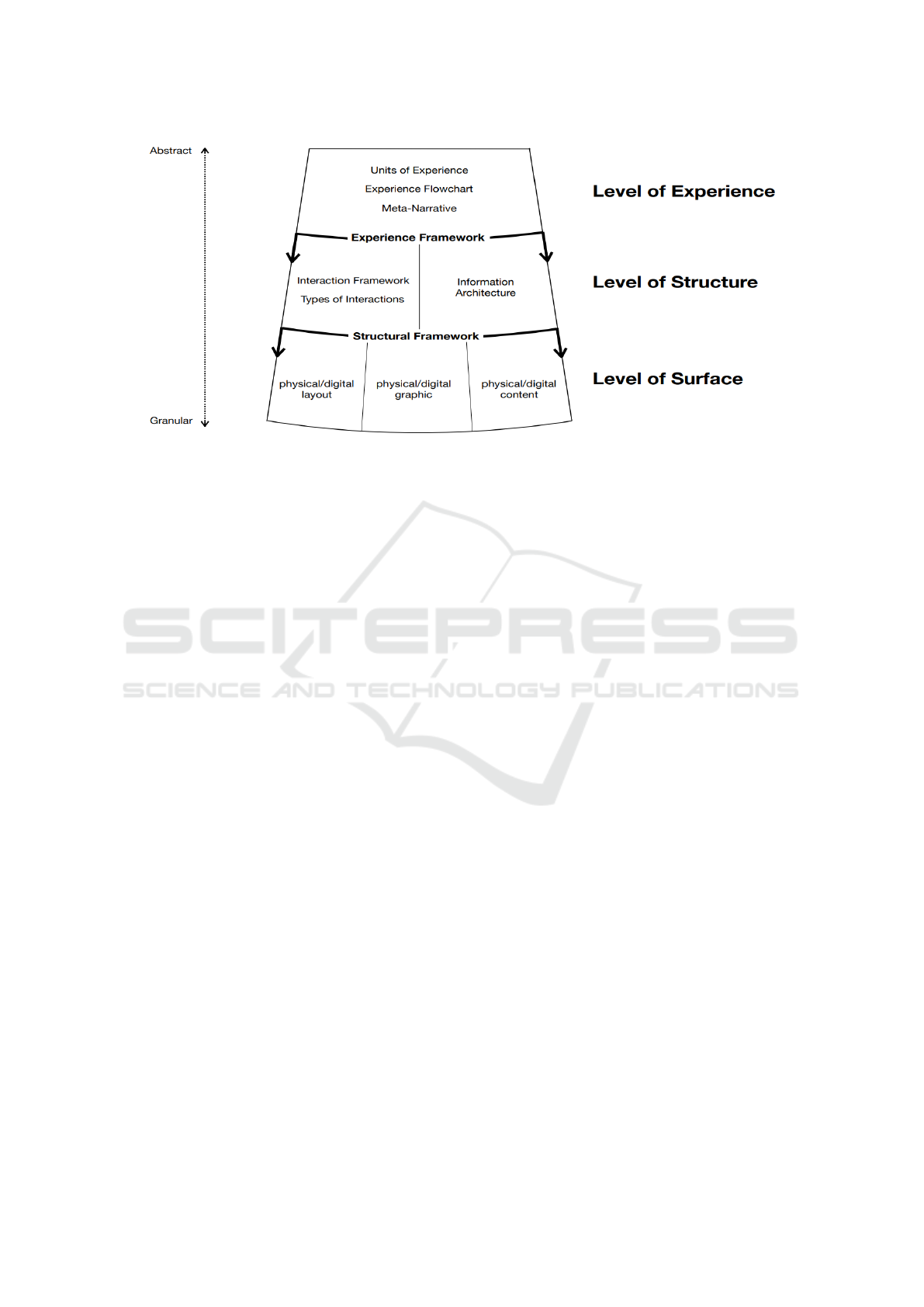

reference framework going from abstract to concrete

(Mason, 2020) depicted in Figure 7:

• User experience level: covering goals, key mes-

sages, high-level narrative.

• Experience framework: based interaction frame-

work and information architecture (i.e. scenog-

raphy) which can be perceived differently by the

public, especially for people affected by physical,

sensory or cognitive impairments.

• Structural level: physical/digital aspects (layout,

graphics, content...), which should provide a vari-

ety of access modalities for the same content.

Based on this, the most interesting issues relate

to advanced technologies such as the development of

virtual tours or mobile applications to support the mu-

seum scenography. Different approaches exist from

the basic transposition of the physical experience: e.g.

video of a guided tour or a paper guide made available

online. The virtual museum is a more complex case.

It might involve unusual controls which needs to be

validated for accessibility and regarding the learning

curve, e.g. through a tutorial or possibly through a

virtual guide (avatar). The pure transposition of the

physical world into a digital one is interesting for a

hybrid experience (preparation before arrival) but it

might also overload the user with uninteresting infor-

mation/actions (corridor pictures, need to point in the

right direction). It could be interesting to consider a

higher level in our reference framework, i.e. goals and

narratives. This can lead to developing a mobile ap-

plication enabling to relate various artefacts, people,

organisations, technologies through a timeline mech-

anism supplementing a physical visit. It will also help

exploring other relationships beyond what is “hard

coded” in the physical exhibition in a more open way

allowing one to dig more into a domain and favouring

learning (Ponsard and Desmet, 2022).

Another interesting and possibly complementary

approach is gamification: it allows the user (not only

kids) to engage more deeply with the content. The

use of a persona, possibly reflecting user preference

and (dis)-abilities, definitely helps to fine tune the in-

terface to her needs. The profiling introduced for a

visitor can be used as driver here.

From an accessibility perspective, the digital

transformation mainly impacts the access to services

which can be provided remotely (virtual tool) but

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

554

Figure 7: Conceptual framework structured in three levels(Mason, 2020).

also supports physical access, for example during the

preparation phase (pre-visit, booking). Those ex-

tended and hybrid scenarios can open the way to an

alternative experience but also possibly create new ac-

cessibility barriers which may frustrate specific users.

Identifying them requires to perform validation and

gather feedback from a variety of profiles, here again

exploring and enriching the set of personas is recom-

mended.

5 CONCLUSION AND NEXT

STEPS

In this paper, we performed a SWOT analysis of

software-based technologies in order to support the

digital transformation of a museum. In order to drive

the process, we identified the main missions and a

set of representative personas. The SWOT analysis

pointed out interesting directions and technologies to

widen the museum experience beyond the physical

space but also beyond the time spent inside the mu-

seum. Different scenarios using mobile applications,

augmented reality and virtual reality were identified

and some existing experiments in museums (with a

focus on computer museums), were reported. Based

on this we could also highlight some useful guidelines

to drive a museum digital transformation and cope

with some new barriers resulting from the extended

use of digital technologies.

Our future work will be to continue the deploy-

ment of such software-based technologies in our mu-

seum. We also plan to extend our analysis to include

more domains and to provide more detailed guide-

lines and lessons learned to overcome specific barriers

like accessibility and also avoiding to “copy/paste”

the physical experience to a digital one.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Thanks to the NAM-IP museum staff and volunteers

for their engagement and contribution to the on-going

museum digital transformation.

REFERENCES

CAWAB. Accessibility Information Portal (in French). http:

//www.access-i.be.

Claris (1985). Filemaker pro.

https://www.claris.com/filemaker.

Coates, C. (2021). How museums are using aug-

mented reality. https://www.museumnext.com/article/

how-museums-are-using-augmented-reality.

Cooper, A. (1999). The inmates are running the asylum.

Macmillan Publishing Company Inc.

Dasgupta, A. et al. (2021). Redefining the digital paradigm

for virtual museums - towards interactive and engag-

ing experiences in the post-pandemic era. In Culture

and Computing - 9th Int. Conf. C&C 2021, July 24-29.

Ferreira., M. J., Moreira., F., and Seruca., I. (2017). Orga-

nizational training within digital transformation: The

toow model. In Proc. of the 19th Int. Conf. on Enter-

prise Information Systems, ICEIS,. SciTePress.

Google (2016). Marzipano. https://www.marzipano.net.

Grudin, J. (2006). Why Personas Work: The Psychologi-

cal Evidence, pages 642–663. The persona lifecycle:

Keeping people in mind edition.

I-maginer (2020). OpenSpace 3D. https://www.

openspace3d.com.

Ismail, M. H., Khater, M., and Zaki, M. (2017). Digi-

tal business transformation and strategy: What do we

know so far. Cambridge Service Alliance, 10:1–35.

A SWOT Analysis of Software Technologies for Driving Museum Digital Transformation

555

ISO (2011). ISO21542:2011 - Building construction — Ac-

cessibility and usability of the built environment.

Jaccede.com. Pour une cit

´

e accessible. http://www.jaccede.

com.

Mason, M. (2020). The elements of visitor experience in

post-digital museum design. Design Principles and

Practices, 14.

Maurer, F. (2021). Business intelligence and innovation: An

european digital innovation hub to increase system in-

teraction and value co-creation within and among ser-

vice systems. In Proc. of the 10th Int. Conf. on Oper-

ations Research and Enterprise Systems, ICORES,.

Parry, R. (2013). The end of the beginning: Normativity

in the postdigital museum. Museum Worlds, 1(1):24 –

39.

Ponsard, C. and Darimont, R. (2017). Quantitative assess-

ment of goal models within and beyond the require-

ments engineering tool: A case study in the accessibil-

ity domain. In Ghanavati, S., Liu, L., and L

´

opez, L.,

editors, Proc. of the 10th International i* Workshop,

Essen, Germany, June 12-13, volume 1829 of CEUR

Workshop Proceedings, pages 13–18. CEUR-WS.org.

Ponsard, C. and Desmet, W. (2022). Historical knowledge

modelling and analysis through ontologies and time-

line extraction operators: Application to computing

heritage. 10th Int. Conf. on Model-Driven Eng. and

Software Development, MODELSWARD, Feb. 6-9.

Ponsard, C., Vanderdonckt, J., and Saintjean, L. (2017). On

the interplay between physical and digital world ac-

cessibility. ERCIM News, 2017(111).

Swank, A. P. (2008). Collection manage-

ment systems. http://carlibrary.org/

Collection-Management-Systems-Swank.pdf.

Vanderdonckt, J. and Beirekdar, A. (2005). Automated web

evaluation by guideline review. J. Web Eng., 4(2).

W3C. Web Accessibility Initiative. https://www.w3.org/

WAI.

W3C. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. ”http://www.

w3.org/TR/WCAG.

Whirl-i-Gig (2012). Collectiveaccess free, open-

source software for cataloguing and pub-

lishing museum and archival collections.

https://www.collectiveaccess.org/.

Zuanni, C. (2020). Mapping museum digital ini-

tiatives during COVID-19. https://tinyurl.com/

museum-di-covid19.

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

556