Diversity of Open Intellectual Capital Acquisition by SMEs of

Different Branches

Tomasz Sierotowicz

a

Department of Economics and Innovation, Institute of Economics, Finance and Management,

Faculty of Management and Social Communication, Jagiellonian University, Prof. Lojasiewicza 4, 30-348, Krakow, Poland

Keywords: Open Intellectual Capital, Acquisition of Open Intellectual Capital, Intellectual Capital, Empirical

Comparative Analysis.

Abstract: Research studies on intellectual capital (IC) focus on its utilisation by mainly large enterprises and its effect

on selected indicators. IC is subject to single-stream analyses as an internal enterprise resource. Because IC

is used in the business operations of enterprises, it must be acquired. This paper presents the results of research

conducted in an unexplored field of IC acquisition. This research focused on innovative small- and medium-

sized enterprises (SMEs) belonging to the two branches of software and hardware development in Poland

(2008–2019). Empirical data were obtained in time series form using dedicated statistical tools, including the

dynamic rate. The main conclusion of a comparative analysis revealed that IC acquisition in the SMEs in this

research should be described as a simultaneous dual-stream (internal and external) process, and IC acquisition

differs significantly between compared branches. Thus, the open IC (OIC) concept should be used in IC

acquisition research. Future research can focus on comparative analyses of enterprises belonged to different

branches, thereby extending our knowledge of the importance of OIC in business.

1 INTRODUCTION

Intangible assets are indicated with increasing

frequency as an important factor in the knowledge

economy for sustained growth, success and increased

enterprise market value (Barney and Hesterly, 2019).

Intangible resources, particularly intellectual capital

(IC), are perceived by large enterprises as strategic for

sustained growth and success (Edvinsson and

Malone, 1997; Santis et al., 2019; Stewart, 1998;

Sveiby, 2001). The use of many different IC

components and their constituent parts is dictated

principally by the needs of enterprises’ business

activities.

The research presented in the literature mainly

addresses large enterprises and questions relating to

the transfer of knowledge inside and outside of these

enterprises (Alimov and Officer, 2017; Matricano et

al., 2020). They focus on topics such as IC value

measurement (Pulic, 2004; Wiederhold, 2014), the

share of IC in the market value of an enterprise

(Mačerinskienė and Survilaitė, 2019; Yovita et al.,

2018), value-added creation in an enterprise

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1462-8267

(Abeysekera, 2021; Pike and Roos, 2000) and other

selected outputs and indicators achieved by that group

of enterprises (Nazari, 2015; Roos and Pike, 2018;

Santis et al., 2019). These studies conclude that

specific IC components are used in line with the types

and in-depth knowledge of the individual conditions

of large enterprises’ business activities. The results of

these studies are widely used in developing IC

models. Particular attention is paid to the models that

aim to describe the effect of IC use on selected indices

and performance indicators (Hejase et al., 2016; Lee

and Wong, 2019).

However, management practice indicates that IC

is not a self-renewable resource; it must be actively

acquired and developed by enterprises. Thus, the

utilisation and the acquisition of IC must be

considered equally important key processes in the

business activities of any enterprise regardless of their

size and branch. Intellectual capital must first be

acquired to the extent necessary to ensure the

continuity of an enterprise’s business activities. Since

IC must be acquired before it is used, it can be

assumed that IC acquisition also represents a

Sierotowicz, T.

Diversity of Open Intellectual Capital Acquisition by SMEs of Different Branches.

DOI: 10.5220/0011337400003280

In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies (ICSBT 2022), pages 69-79

ISBN: 978-989-758-587-6; ISSN: 2184-772X

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

69

systematic and continual process related to an

enterprise’s business activities. The above reasons

underlie the choice of innovative small- and medium-

sized enterprises (SMEs) belonging to different

branches conducting their business activities in

Poland. Since IC acquisition and use are equally

important, the absence of research on IC acquisition

represents a major gap in our knowledge.

Another gap in the literature on this subject is the

absence of studies covering relatively long periods.

Most analyses are limited to one year, which provides

only a snapshot of the results. The presented reasons

are important barriers to conducting comparative

research on IC. Therefore, the research presented in

this paper aims to fill the above-mentioned gaps.

This study aims to present and discuss the results

of research on the comparative analysis and

evaluation of open IC (OIC) acquisition performed by

SMEs belonging to different branches and conducting

business activities in Poland as observed over 12

years of time period.

2 MATERIALS AND METHOD

It is important to note that SMEs in the two branches

covered by the research conduct different business

activities. The first branch consisted of SMEs that

develop software in Poland (and belong to the branch

of knowledge-intensive services). Their business is

described in Nomenclature statistique des Activités

économiques dans la Communauté Européenne

(NACE) classes 62.01 and 62.02 (European

Communities, 2008). For simplicity of description, it

is termed in this paper as branch 62. The second

branch consisted of SMEs that manufacture

computer, electronic and optical products (and belong

to the high-tech manufacturing [hardware] branch).

Their business is described in NACE classes 26.11,

26.12, 26.20, 26.30, 26.40, 26.51, 26.52, 26.70 and

26.80 (European Communities, 2008). For simplicity

of description, it is termed in this paper as branch 26.

Nowadays, information and communication

technology (ICT) equipment is composed of

hardware and software products. Although these

branches represent significantly different business

activities, their products are unavoidable parts of

today’s ICT tools. The above-mentioned branches

conduct different business activities, and at the same

time, their products are integrated in nowadays

communication equipment. The above-mentioned

issues were arguments why these two branches were

selected for inclusion in the research. Because the

business activities of these two branches differ

significantly, an important main research question

was raised: Does the acquisition of OIC indicate

differentiation between the branches covered by the

research? To answer the main research question, the

following detailed questions were formulated:

1. Was OIC acquired simultaneously and

continuously in two entire streams (internal and

external) in both branches over the entire research

period?

2. Which OIC acquisition stream was more

important for the surveyed SMEs in both branches

considering the level of acquisition of that capital?

3. Which OIC acquisition stream was more

important for the surveyed SMEs in both branches

considering the dynamic rate of change in the OIC

acquisition level?

4. Which acquired OIC components were most

important for the surveyed SMEs in both branches

considering the share and dynamic rate of change in

the levels of each component acquisition?

An analysis was conducted over the three stages

described below to answer the above-mentioned

questions.

2.1 Description of Open Intellectual

Capital Concepts

The first stage was to propose the broadest IC concept

used in this research. It was an important stage since

there is no universal concept of IC in the literature.

Many IC concepts proposed in the literature on the

subject vary in component sets. Thus, an IC concept

including as many components as possible was used

as a basis to develop the IC for this research. The

concept of IC proposed here is as broad as possible.

It includes numerous components, facilitating a more

detailed analysis and evaluation of the IC acquisition

process. Also, it was useful because only the selected

components and their constituent parts, which create

the structure of IC, are utilised in the SME operations

covered by this research. Based on managerial

practice, it can be assumed that enterprises differ in

their utilisation of IC. It depends on many enterprises’

external factors, such as the social and economic

environments, the industry and internal factors related

to individual conditions of enterprises, e.g. their size

and employees’ educational backgrounds and

occupational experience.

The concept used in this research was formulated

according to the rule of the uniqueness of IC

components. Considering the most comprehensive IC

concepts in terms of their components and constituent

parts, which are also popular in the literature, and

following the above rule, an IC concept consisting of

ICSBT 2022 - 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

70

the following components was developed and used in

this research:

• Human capital;

• Organisational capital;

• Relational capital;

• Project capital;

• Innovation capital;

• Information capital;

• Technological capital.

A survey was conducted with an identical component

structure but divided into separate internal and

external IC acquisition streams. These OIC

components were acquired by SMEs covered by the

research. The internal stream describes IC generation

internally within the surveyed SMEs based on their

own resources. The external stream describes the IC

acquisition process from the external environment of

the surveyed SMEs. For methodological reasons,

comparative analyses required the same IC

component structure in both (symmetric) streams.

Thus, the formulated concept was termed OIC.

The second stage of this research was to analyse

and evaluate the dynamics of OIC acquisition at the

level of two symmetric, simultaneous and

independent (internal and external) streams in the

SMEs covered by the research.

The third stage of this research was to

independently analyse and evaluate the dynamics of

OIC acquisition at the component level for the

internal and external streams in the SMEs covered by

the research.

To answer the research questions, comparative

analyses were made at the level of the streams and the

individual OIC components that constitute the

internal and external streams of capital acquisition.

2.2 Empirical Data, Research Period

and SMEs Covered by the

Research Project

The set of variables describing individual OIC

components, which were symmetric in the internal

and external streams for both branches covered by the

research, was obtained and compiled based on a form

used in a regular survey for innovative entities. In the

form of a time series, the original empirical data set

was obtained from a regular survey conducted by

Statistics Poland.

The survey covered two groups of innovative

SMEs belonging to different branches described

above in chapter 2. Branch 62 consisted of SMEs that

develop software in Poland and branch 26 consisted

of SMEs that manufacture computer, electronic and

optical products. Both branches were covered by the

entire research period of 12 years, from 2008 to 2019.

The SMEs covered by the research in both branches

were characterised by the number of employees,

which varied from 10 to 249. The population of the

surveyed group is given in Table 1.

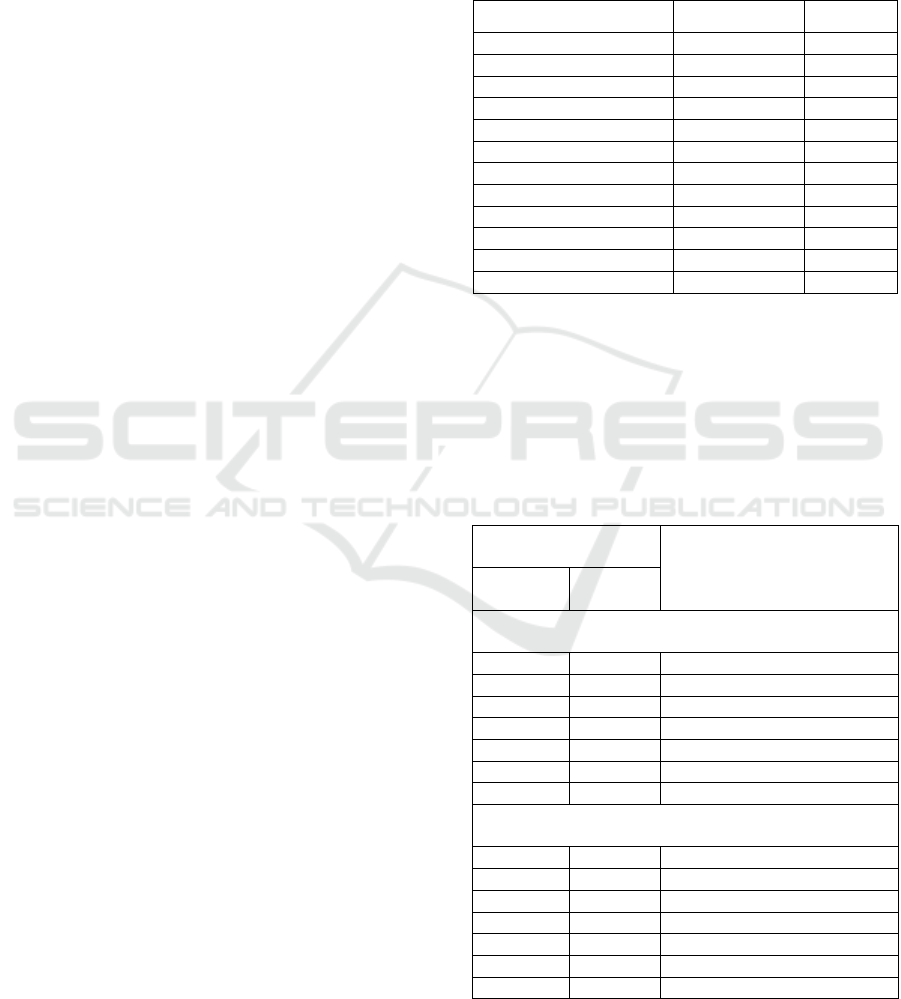

Table 1: Number of SMEs covered by the research.

Year / Number of SMEs Branch 62 Branch 26

2008 278 186

2009 291 185

2010 269 181

2011 306 193

2012 314 177

2013 347 168

2014 338 198

2015 345 211

2016 352 224

2017 367 222

2018 382 205

2019 403 196

The time series contained 12 annual observations;

these covered the research period of 2008–2019 and

described each acquired by SMEs covered by the

research component constituting OIC separately in

the internal and external streams and branches studied

(Table 2).

Table 2: Time series of the variables used in the performed

comparative analysis.

Streams of OIC

ac

q

uire

d

com

p

onents

Description of variables

characterising the acquiring of

OIC

Branch 62

Branch

26

Streams of components forming the internal stream of

acquired OI

C

i

62_1

i

26_1

Human Ca

p

ital

i

62_2

i

26_2

Or

g

anisational Ca

p

ital

i

62_3

i

26_3

Relational Ca

p

ital

i

62_4

i

26_4

Technological Capital

i

62_5

i

26_5

Information Capital

i

62_6

i

26_6

Project Capital

i

62_7

i

26_7

Innovation Ca

p

ital

Streams of components forming the external stream of

acquired OI

C

e

62_8

e

26_8

Human Capital

e

62_9

e

26_9

Or

g

anisational Ca

p

ital

e

62_10

e

26_10

Relational Ca

p

ital

e

62_11

e

26_11

Technological Capital

e

62_12

e

26_12

Information Capital

e

62_13

e

26_13

Project Capital

e

62_14

e

26_14

Innovation Ca

p

ital

The different variables characterise topics directly

related to the acquisition of OIC and are

Diversity of Open Intellectual Capital Acquisition by SMEs of Different Branches

71

indispensable to the business conducted by the SMEs

studied in both branches. Thus, this research

conducted a comparative analysis and evaluation of

OIC acquisition in both branches to answer the

research questions. Such analysis and evaluation

required purposefully selected computational tools

and the division of OIC acquisition into internal and

external streams (both at the component level and the

stream level) separately for the SMEs in the two

branches covered by this research.

2.3 Empirical Analysis in the Internal

and External Streams Level of

Open Intellectual Capital

Acquisition

The calculations in the second stage of analysis and

evaluation consider the level of OIC acquisition in the

internal and external streams over the entire research

period. They were performed based on variables

forming a time series of annual empirical

observations of the acquired constituent parts

comprising each of the structural components of OIC.

The level of OIC acquisition in the internal stream

was calculated using the variables marked in Table 2

as i

62_1

– i

62_7

for the SMEs belonging to branch 62

and i

26_1

– i

26_7

for those belonging to branch 26 of the

enterprises covered by this research. Similarly, the

level of OIC acquisition in the external stream was

calculated using the variables marked in Table 2 as

i

62_8

– i

62_14

for the SMEs belonging to branch 62 and

i

26_8

– i

26_14

for SMEs belonging to branch 26 of the

enterprises covered by this research. Consequently,

both streams in both branches consist of similar

groups of seven components and their constituent

parts, which form the OIC structure in each year of

the research period. Thus, unit streams of individual

OIC component acquisition levels could be used to

build an index of the overall level of OIC acquisition

for each branch covered by this research, which was

calculated according to Equation 1:

()

,

b

b

7

ibt

i=1

inbt

sbt

14

exbt

jbt

j=8

v

v

ind = = , t = 2008,...,2019

v

v

∀

(1)

where:

t – the subsequent year in the time series;

b – the index (from 1 to 2) denoting branches covered

by the research: b = 1 for SMEs belonging to branch

62 and b = 2 for SMEs belonging to branch 26 (Table

2);

i

b

– the index of each variable i

62_1

– i

62_7

for b = 1

and i

26_1

– i

26_7

for b = 2, representing the subsequent

component of OIC in the internal stream of both

branches covered by the research;

v

ibt

– the level of the acquired subsequent component

i, of OIC in the internal stream (calculated in

subsequent branch b and year t);

v

inbt

– the level of the acquired internal stream of OIC

(calculated in subsequent branch b and year t);

j

b

– the index of each variable i

62_8

– i

62_14

for b = 1

and i

26_8

– i

26_14

for b = 2 representing the subsequent

component of OIC in the external stream of both

branches covered by the research;

v

jtb

– the level of the acquired subsequent component

j of OIC in the external stream in subsequent branch

b and year t;

v

exbt

– the level of the acquired external stream of OIC

(calculated in subsequent branch b and year t), and

ind

sbt

– indices of the overall OIC acquisition by the

SMEs covered by this research (calculated in

subsequent branch b and year t).

The calculated value of the indices of the overall

OIC acquisition ind

stb

provides information for each

branch covered by this research as to whether OIC is

acquired in both streams simultaneously, continually

and systematically. It also indicates which stream of

OIC acquisition reached a higher level in the

surveyed SMEs in each branch in each year of the

research period. The calculated indices provide

answers to the first and second research questions.

The values of obtained variables i

inbt

, i

exbt

and

ind

sbt

, which take the form of time series, were used

to analyse the dynamic rate of change in OIC

acquisition in the surveyed SMEs in both branches

over the entire research period (Hatcher, 2013;

Sharpe et al., 2014). The dynamic rate of change in

the above-described time series was calculated

according to Equation 2:

()

,

N

b(t)

N1

nb

t=2

b(t 1)

n

T = 1 ×100%, t = 2008,...,2019

n

−

−

−∀

∏

(2)

where:

t – the subsequent year in the time series;

N – the number of annual observations in a time series

of the subsequent variable calculated in that stage of

research in the adopted research period;

b – the index ranging from 1 to 2 and denoting

branches covered by the research: b = 1 for SMEs

belonging to branch 62 and b = 2 for SMEs belonging

to branch 26 (Table 2);

n

b(t)

– the three calculated variables denoted in each

internal and external stream, branch b and year t: n

1

–

ICSBT 2022 - 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

72

i

int1(t)

, n

2

– i

ext1(t)

, n

3

– ind

s1(t)

, n

4

– i

in2(t)

, n

5

– i

ex2(t)

, n

6

–

ind

s2(t)

;

b(t)

b(t 1)

n

n

−

– the next chain index value of the three

calculated variables denoted in the internal and

external stream and branch b, and year t;

nb

T

– the value of the dynamic rate of change in each

of the three calculated variables denoted in each

branch b, respectively:

1in1

TTi−

,

2 ex1

TTi−

,

3s1

TTind−

,

4in2

TTi−

,

5 ext2

TTi−

,

6s2

TTind−

.

An interpretation of the dynamic rate of change

nb

T

answers the third research question. As the dynamic

rate of change exceeds 1, the level of OIC acquisition

rises; this means that IC becomes increasingly

important for the business activities that take place in

the surveyed SMEs in both branches since OIC is

acquired in line with the demand created by these

activities. This tool is also useful in determining the

dynamic rate of change in the acquisition level

separately for the internal and external streams of

OIC in the SMEs of both branches over the entire

research period.

2.4 Empirical Analysis in the Internal

and External Component Level of

Open Intellectual Capital

Acquisition

The third stage of analysis and evaluation is aimed at

analysing the dynamic rates of change in OIC

acquisition by the SMEs of both branches at the

component level constituting the internal and external

streams. This stage consists of the two phases

described below, which address different aspects of

the analysis and evaluation of the diversified

acquisition of OIC at the component level. Phase 1 of

Stage 3 was dedicated to analysing and evaluating the

share of individual OIC component acquisition levels

in the internal and external streams separately for

both branches over the entire research period. The

share of individual OIC component acquisition levels

in the internal stream in both branches over the entire

research period was calculated according to Equation

3:

()

()

() ()

,

2019

ib t

t=2008

ib

2019

ib t jb t

t=2008

in

Inc = ×100%, t = 2008,...,2019; i = 1,...,7; j = 8,...,14

in +ex

∀

(3)

where:

t – the subsequent year in the time series;

b – the index ranging from 1 to 2 and denoting

branches covered by the research: b = 1 for SMEs

belonging to branch 62, and b = 2 for SMEs

belonging to branch 26 (Table 2);

i

b

– the index of each variable i

62_1

– i

62_7

for b = 1

and i

26_1

– i

26_7

for b = 2, representing the subsequent

component of OIC in the internal stream of both

branches covered by the research;

j

b

– the index of each variable i

62_8

– i

62_14

for b = 1

and i

26_8

– i

26_14

for b = 2 representing the subsequent

component of OIC in the external stream of both

branches covered by the research;

in

ib(t)

– the acquisition level of subsequent component

i included in the internal stream of OIC acquisition by

the surveyed SMEs in branch b and subsequent year t

of the research period;

ex

jb(t)

– the acquisition level of subsequent component

j included in the external stream of OIC acquisition

by the surveyed SMEs in branch b and subsequent

year t of the research period, and

Inc

ib

– the share of the acquisition level of subsequent

component i included in the internal stream of OIC

acquired by the surveyed SMEs in branch b over the

entire research period.

The share of individual OIC component

acquisition levels in the external stream in both

branches over the entire research period was

calculated according to Equation 4:

()

()

() ()

,

2019

jb t

t=2008

jb

2019

ib t jb t

t=2008

ex

Exc = ×100%, t = 2008,...,2019; i = 1,...,7; j = 8,...,14

in + ex

∀

(4)

where:

t – the subsequent year in the time series;

b – the index ranging from 1 to 2 and denoting

branches covered by the research: b – 1 for SMEs

belonging to branch 62 and b – 2 for SMEs belonging

to branch 26 (Table 2);

i

b

– the index of each variable i

62_1

– i

62_7

for b – 1 and

i

26_1

– i

26_7

for b – 2, representing the subsequent

component of OIC in the internal stream of both

branches covered by the research;

j

b

– the index of each variable i

62_8

– i

62_14

for b – 1

and i

26_8

– i

26_14

for b – 2 representing the subsequent

component of OIC in the external stream of both

branches covered by the research;

in

ib(t)

– the acquisition level of subsequent component

i included in the internal stream of OIC acquisition by

the surveyed SMEs in branch b and subsequent year t

of the research period;

ex

jb(t)

– the acquisition level of subsequent component

j included in the external stream of OIC acquisition

by the surveyed SMEs in branch b and subsequent

year t of the research period, and

Diversity of Open Intellectual Capital Acquisition by SMEs of Different Branches

73

Exc

jb

– the share of the acquisition level of subsequent

component j included in the external stream of OIC

acquired by the surveyed SMEs in branch b over the

entire research period.

Phase 2 of Stage 3 was dedicated to analysing and

evaluating the dynamic rate of change in each

component of the acquired OIC in both branches

covered by this research (Hatcher, 2013; Sharpe et al.,

2014). The dynamic rate of change in this section was

calculated according to Equation 5:

,

N

bcs(t)

N1

bcs

t=2

bcs(t 1)

v

T = 1 ×100%, c = 1,...,7; s = 1,2

v

−

−

−∀

∏

(5)

where:

t – the subsequent year in the time series;

N – the number of annual observations in the time

series of the subsequent components included in the

OIC acquired by the surveyed SMEs over the adopted

research period;

b – the index ranging from 1 to 2 and denoting

branches covered by the research: b – 1 for SMEs

belonging to branch 62 and b – 2 for SMEs belonging

to branch 26 (Table 2);

c – an index ranging from 1 to 7, denoting subsequent

components included in the OIC acquired by the

surveyed SMEs over the adopted research period;

s – index 1 or 2 indicating, respectively, the internal

or external stream of OIC acquisition by the SMEs

covered by the research;

bcs(t)

bcs(t 1)

v

v

−

– another value of a chain index in the time

series of the acquisition level of subsequent

component c included in the OIC acquired by the

surveyed SMEs in branch b and subsequent year t of

the research period; and

bcs

T

– the dynamic rate of change in the acquisition

level of component c (included in the OIC acquired

by the surveyed SMEs in branch b) over the entire

research period in the internal and external stream (s)

separately.

The share of individual OIC component

acquisition levels in the internal and external streams

of the SMEs belonging to both branches and the

dynamic rate of change

bcs

T

calculated in this phase

allowed to answer the fourth research question. As the

dynamic rate of change exceeds 1, the level of

acquisition of an OIC component rises, which means

that IC becomes increasingly important for the

business activities of the surveyed SMEs since OIC is

acquired in line with the demand created by these

activities.

3 RESEARCH RESULTS

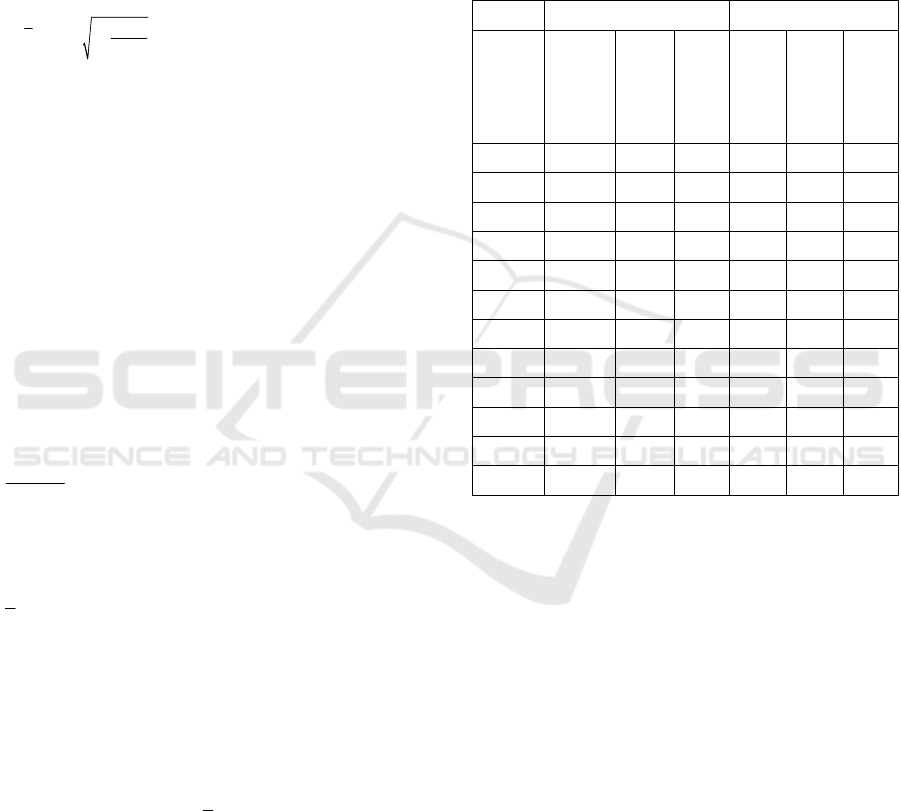

The results of the calculated annual indices of the

overall OIC acquisition level ind

s1t

and ind

s2t

of the

SMEs covered by the research and belonging to

branches 62 and 26, respectively, are shown in Table

3. They were obtained from Equation 1.

Table 3: Calculated results of the OIC acquisition level by

the SMEs of branches 62 and 26.

Branch 62 Branch 26

Year /

Designation

v

in1t

[number]

v

ex1t

[number]

ind

s1t

v

in2t

[number]

v

ex2t

[number]

ind

s2t

2008 698 494 1.412 335 492 0.681

2009 836 576 1.451 408 576 0.701

2010 707 486 1.454 439 580 0.756

2011 643 518 1.241 476 642 0.741

2012 739 496 1.489 464 584 0.794

2013 945 534 1.769 462 555 0.832

2014 743 554 1.341 549 604 0.908

2015 980 571 1.761 602 632 0.952

2016 787 592 1.329 656 698 0.939

2017 895 652 1.372 643 719 0.894

2018 1151 785 1.466 545 811 0.672

2019 1162 879 1.321 490 717 0.683

The obtained calculation results indicate that the

values of index ind

s1t

, which represents those covered

by the research SMEs of branch 62, are greater than

1. In comparison, index ind

s2t

, which represents the

SMEs belonging to branch 26, is lower than 1 in each

year of the research period. Thus, the comparative

analysis reveals that IC was acquired by the surveyed

SMEs in both branches simultaneously, continually

and systematically during the entire research period

in the two internal and external streams because the

variables in v

in1t

and v

ex1t

describe branch 62, and v

in2t

,

v

ex2t

describe branch 26, assuming positive values

(Table 3).

The values of index ind

s1t

, which represents the

SMEs belonging to branch 62, are greater than 1

(Figure 1). Thus, considering the level of OIC

acquisition, the internal stream is more important for

the software-developing SMEs of branch 62 since its

OIC acquisition level is greater than the acquisition

level of OIC in the external stream (i.e. the variable

v

in1t

is greater than v

ex1t

).

ICSBT 2022 - 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

74

Figure 1: Diversified level of OIC acquisition in branches

62 and 26.

The opposite situation reveals the values of index

ind

s2t

, which represents the SMEs belonging to

branch 26, which are lower than 1 (Figure 1) in each

year of the research period. It signifies that the

external stream is more important for the hardware-

producing SMEs of branch 26 since its OIC

acquisition level is greater than the acquisition level

of OIC in the internal stream (i.e. the variable v

ext2t

is

greater than v

in2t

). The conclusions presented above

answer the first and second research questions. Table

4 shows the results obtained using Equation 2 to

determine the dynamic rate of change in OIC

acquisition in the internal and external streams and

the overall OIC acquisition of the SMEs representing

branches 62 and 26 covered by the research.

Table 4: Calculated dynamic rates of change in the level of

OIC acquisition in branches 62 and 26.

Branch 62 Branch 26

in1

Ti

ex1

Ti

1

Tind

in2

Ti

ext2

Ti

2

Tind

4.74% 5.38% -0.60% 3.52% 3.48% 0.03%

The calculation results indicate that the level of

OIC acquisition in the internal and external streams

rose year on year by 4.74% and 5.38%, respectively,

on average, over the entire research period for the

SMEs belonging to branch 62. A similar situation

reveals the results for SMEs belonging to branch 26,

for which OIC acquisition in the internal and external

streams rose year on year by 3.52% and 3.48%,

respectively, on average, over the entire research

period. The indices of the overall OIC level decreased

year on year by 0.60%, on average, over the entire

research period for branch 62, while they rose year on

year by 0.03% for branch 26. The results of the

comparative analysis allowed to conclude that in both

branches, the internal and external levels of OIC

acquisition rose year on year over the entire research

period. However, in conjunction with the results

presented in Figure 1, the comparative analysis led to

the conclusion that there is opposite importance of

streams of the OIC acquisition in both branches. In

branch 62, the internal stream is more important,

while in branch 26, the external stream is more

important. This situation can be interpreted via the

direct relation of acquired IC to business activities.

The SMEs in branch 62 generated more added value

to the software-developing products in their internal

environment than those producing hardware and

belonging to branch 26. The main conclusion is that

although the SMEs in both branches are innovative,

those in branch 62 are more creative, while those in

branch 26 are more reproductive.

Table 5 shows the calculation results of the

individual components of the OIC acquisition level

separately in the internal and external streams as a

share of overall OIC acquisition for both compared

branches over the entire research period. The

calculations were performed according to Equations

3 and 4. The results obtained indicate that the

surveyed SMEs belonging to branch 62 acquired the

highest share of acquisition over the entire research

period, indicating both innovation and project capital.

These results answer the fourth research question.

Table 5: Calculated values of component share in OIC

acquisition over the entire research period.

B

ranch 62

OIC component

Internal

stream

External

stream

Innovation Capital 84.99% 15.01%

Project Capital 81.00% 19.00%

Information Capital 70.28% 29.72%

Human Ca

p

ital 52.82% 47.18%

Or

g

anisational Ca

p

ital 39.68% 60.32%

Relational Ca

p

ital 30.02% 69.98%

Technological Capital 0.00% 100.00%

B

ranch 2

6

OIC component

Internal

stream

External

stream

Innovation Capital 34.93% 65.07%

Project Capital 26.54% 73.46%

Information Ca

p

ital 43.69% 56.31%

Human Ca

p

ital 55.77% 44.23%

Or

g

anisational Ca

p

ital 60.61% 39.39%

Relational Capital 37.58% 62.42%

Technological Capital 72.30% 27.70%

Diversity of Open Intellectual Capital Acquisition by SMEs of Different Branches

75

Innovative solutions and knowledge of IT project

management techniques principally through the

internal stream. The managerial techniques are

adapted to the individual conditions in each enterprise

so that the processes of software development and

improvement are managed to create the maximum

added value represented by an innovative product.

Technological and relational capital were mostly

acquired in the external stream. The technological

capital component includes computer technologies

and equipment, which proves that in the software-

developing SMEs of branch 62, the computer

programming environment (which consists of

suitable software, IT technologies and computer

equipment) does not result from their operational

activities but is acquired from external parties. The

relational capital component consists of a list of

regular customers and the SMEs’ partners, image,

trust, reputation and external relations. This

component was also obtained mostly by the SMEs

representing branch 26. Thus, the result confirms that

these constituent parts are strictly related to the

external social and economic environment of SMEs

belonging to both compared branches.

In addition, the SMEs belonging to branch 26

acquired mostly project and innovation capital in the

external stream, while in the internal stream, these

SMEs acquired mostly technological and

organisational capital. Conversely, human capital

was acquired in both streams at a similar level in both

compared branches. This result answers the fourth

research question.

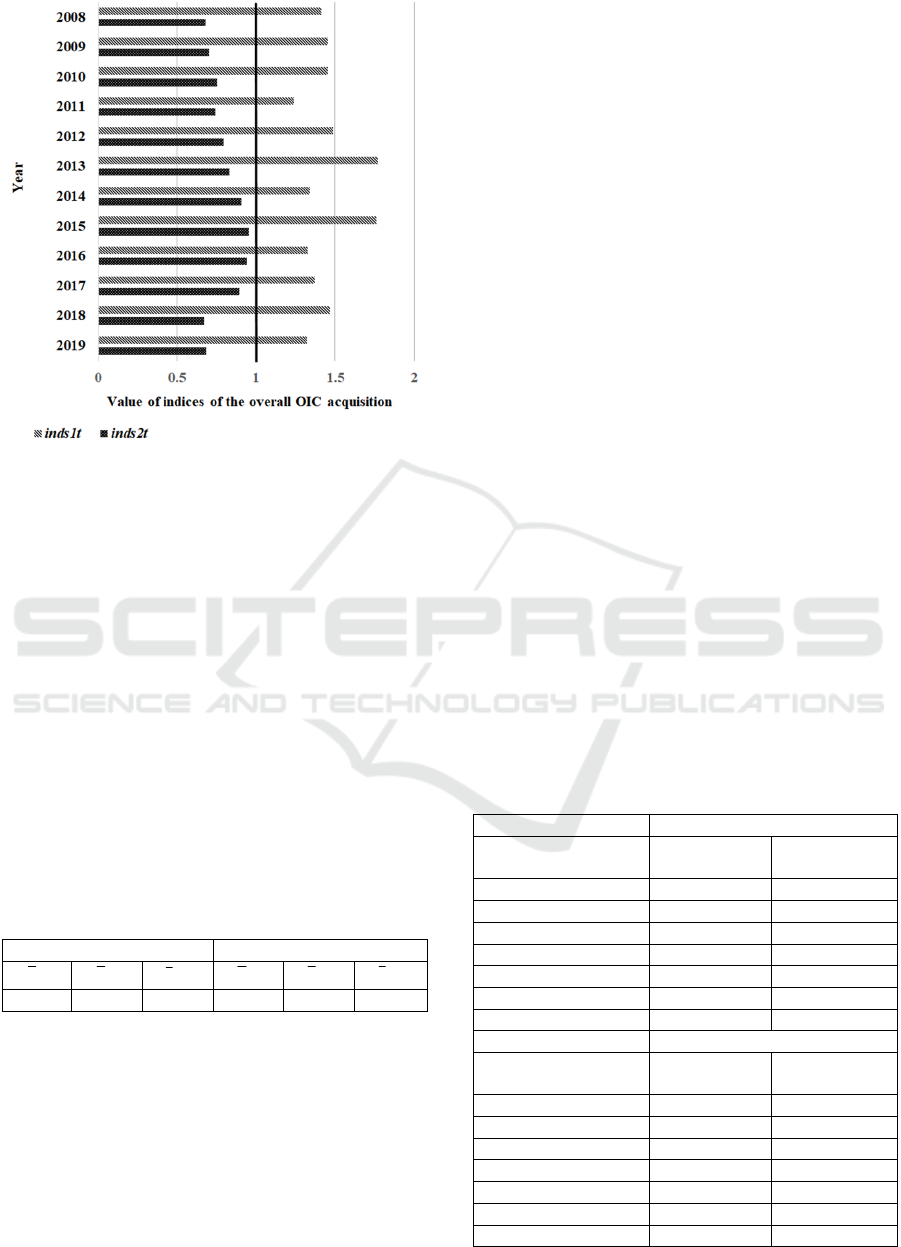

The calculation results above demonstrate that

OIC acquisition at the component level clearly varied

in both streams and compared branches. This

conclusion is confirmed by the graphical

representation of the internal and external streams of

OIC acquisition at the component level. Figure 2

shows the spectrum of OIC acquisition by the SMEs

belonging to branch 62. Figure 2 indicates that the

intersection of acquisition is insignificant, and the

larger areas are clearly different. These results lead to

the conclusion that the SMEs belonging to branch 62

acquired components mostly in the internal and

external OIC streams, and these acquisitions were

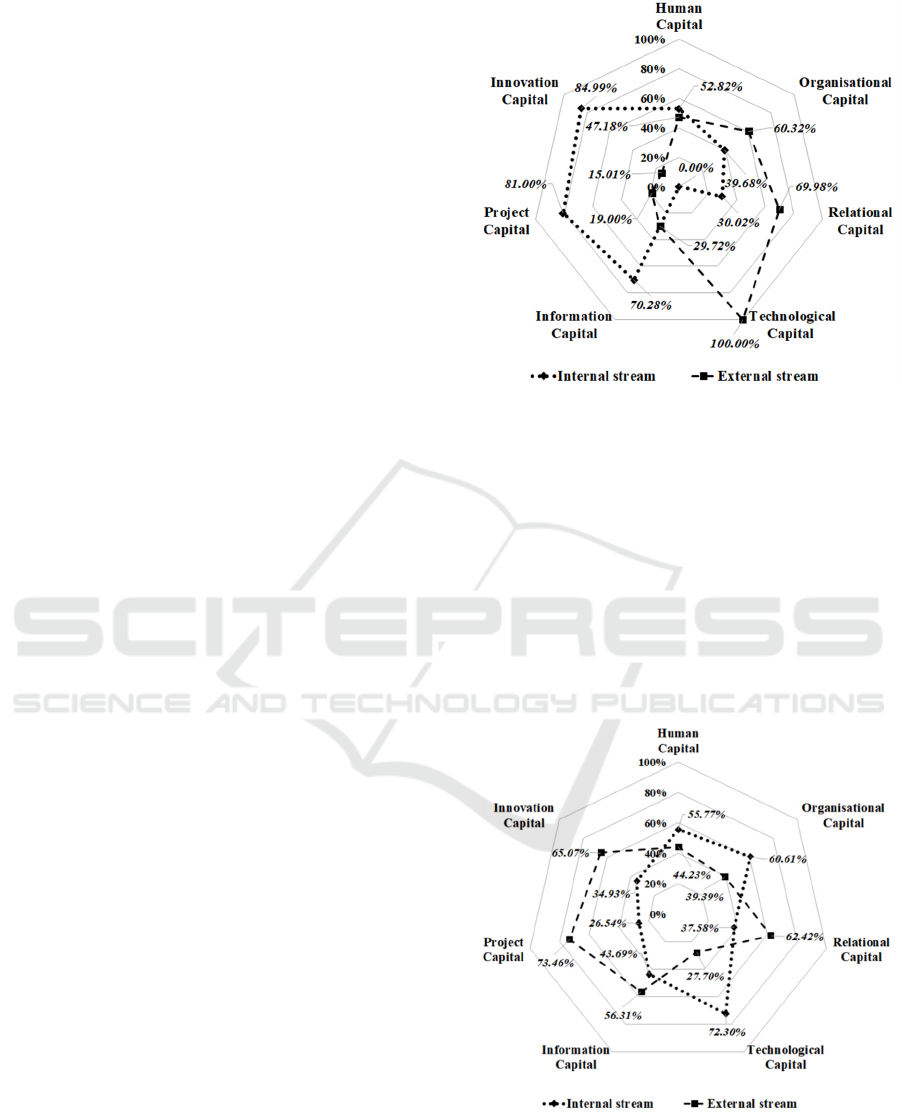

complementary. Figure 3 presents the spectrum of

OIC acquisition by the SMEs belonging to branch 26.

Conversely, Figure 3 shows that the intersection of

acquisition is significant, and the smaller areas are

clearly different. These results lead to the conclusion

that SMEs belonging to branch 26 components

acquired in the internal and external OIC streams, but

they are less complementary than in branch 62.

Figure 2: Diversified acquisition of OIC components in

branch 62.

Furthermore, a close examination of the locations of

the internal and external streams in Figures 2 and 3

reveal that they are located in opposing areas. The

external boundary of the internal stream of OIC

acquisition in branch 62 is designated by the

following components: human capital, innovation

capital, project capital and information capital (Figure

2). Three of these (innovation capital, project capital

and relational capital) designate the boundary of the

external stream of OIC acquisition in branch 26

(Figure 3).

Figure 3: Diversified acquisition of OIC components in

branch 26.

This situation indicates that the component

acquisition of OIC reveals significant differentiation

between the compared branches.

ICSBT 2022 - 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

76

Table 6 presents the results of the dynamic rate of

change calculation in the level of the acquisition of

individual OIC components separately in the internal

and external streams for branches 62 and 26 over the

entire research period. The calculations were

performed according to Equation 5.

Table 6: Calculated dynamic rates of change in acquisition

of the OIC components for branches 62 and 26.

B

ranch 62

OIC components

Internal

strea

m

External

strea

m

Human Capital 8.48% 10.13%

Organisational Capital 1.74% 3.11%

Relational Capital 4.13% 1.58%

Technolo

g

ical Ca

p

ital - 2.65%

Information Ca

p

ital 4.34% 8.03%

Pro

j

ect Ca

p

ital 3.82% 7.01%

Innovation Capital 4.54% 5.63%

B

ranch 2

6

OIC components

Internal

strea

m

External

strea

m

Human Capital 6.88% 6.93%

Organisational Capital 6.01% 0.30%

Relational Ca

p

ital 5.74% -1.32%

Technolo

g

ical Ca

p

ital 8.81% -7.61%

Information Ca

p

ital 1.82% 7.78%

Project Capital -1.70% 5.67%

Innovation Capital -2.65% 4.73%

The obtained calculation results indicated that for

the SMEs belonging to branch 62, human capital

grew in importance more than other components in

both streams of this branch (Table 6). Furthermore,

the dynamics level of acquisition of the OIC

components increased only in branch 62. Conversely,

the results obtained from the SMEs belonging to

branch 26 indicate a more diversified situation. The

level of acquisition of information capital,

organisational capital and human capital components

increased in both the internal and external streams.

The highest increase in the OIC acquisition level was

for human capital, which was an average of 6.88%

and 6.93%, respectively, year on year over the entire

research period.

Compared with other components, these results

allowed the conclusion that human capital is also one

of the most important components in branch 26. A

very interesting situation indicates the technological

component, where the level of OIC acquisition

increased in the internal stream year on year by 8.81%

and decreased in the external stream year on year by

7.78%. Such results could lead to the conclusion that

a significant part of the business activities of the

SMEs belonging to branch 26 contains not only

hardware production but also services and technical

support for hardware products introduced to the

market.

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

The literature review indicated that research has

focused on the use of IC in business. Those studies

concentrated on the effects of IC use on selected

business indices and enterprise performance

indicators and considered single-stream IC models,

which were understood as an internal enterprise

resource (Dimitrios et al., 2011; McConnell, 2019).

The acquisition of OIC was not often covered by past

research. Thus, IC acquisition seems to be a relatively

new field of study.

Although, the software-developing and hardware

producing businesses significantly evolved in the last

12 years, the management practice suggest that IC is

acquired both internally and externally (Ahmed et al.,

2022). What’s more, SMEs belonged to both

branches could be considered as knowledge-intensive

enterprises. There is almost impossible in nowadays

to create a new ICT equipment produced by SMEs in

both compared branches without acquisition of new

knowledge and technologies in their business

activities (Schiavone et al., 2022). The spread of a

new knowledge and technologies seems to be

unavoidable and play incremental role in business

activities. These issues triggered research into a new

field of IC acquisition that has not been explored

previously. This paper discussed research results

obtained in that field by comparing OIC acquisition

in two separate branches. The research covered

innovative SMEs conducting business activities in

Poland that belonged to two branches: branch 62,

represented by software-developing SMEs, and

branch 26, represented by hardware producing SMEs.

The research results discussed above clearly

demonstrate that the surveyed SMEs in both

compared branches acquire IC continually,

systematically and simultaneously from both external

and internal sources; this answers the first and second

research questions. Consequently, the analysis and

evaluation of IC acquisition, including comparisons

between any branches and groups of selected

enterprises, should be performed using OIC

acquisition concepts which, after being empirically

proven, can be considered an OIC model.

The calculated values of the indices of overall

OIC acquisition indicate that the internal stream is

Diversity of Open Intellectual Capital Acquisition by SMEs of Different Branches

77

more important for the software-developing SMEs

belonging to branch 62. In contrast, the external

stream is more important for the hardware producing

SMEs belonging to branch 26. This is the answer to

the third research question.

Considering the dynamic rate of change in OIC

acquisition at the component level, the results

obtained reveal the significant differentiation

between the compared branches. The OIC acquisition

of each component increased for the SMEs belonging

to branch 62 over the entire research period, while for

those belonging to branch 26, only the level of

acquisition of information capital, organisational

capital and human capital components increased in

both internal and external streams. The results reveal

significant differentiation in the level of OIC

acquisition in terms of project capital, innovation

capital, relational capital and technological capital.

The differences in acquiring OIC components are

related to the different business activities of the SMEs

belonging to the compared branches. Considering the

dynamic rate of change, human capital, project capital

and information capital were most important for the

SMEs belonging to branch 62, while human capital,

information capital and organisation capital were

most important for those belonging to branch 26. This

answers the fourth research question.

Considering the share in the level of acquired OIC

components, for the SMEs belonging to branch 62,

innovation capital and project capital were the most

acquired components in the internal stream.

Relational capital and organisational capital (except

technological capital) were most important in the

external stream. For those SMEs belonging to branch

26, technological capital and organisational capital

were most important in the internal stream. In

contrast, project capital and innovation capital were

most important in the external stream. These results

answer the fourth research question.

In addition, the results of the comparative analysis

of the graphic representation of OIC component

acquisition for branch 62 indicated that the

intersection of acquisition is insignificant, and larger

areas are clearly different since they are located

outside the intersection. This led to the conclusion

that the acquisition of OIC components by the SMEs

belonging to branch 62 is mostly complementary.

However, there is a different situation in branch 26,

where the intersection of acquisition is significant,

and smaller areas are clearly different because they

are located outside the intersection. This led to the

conclusion that the acquisition of OIC components by

the SMEs belonging to branch 26 is significantly less

complementary than for the SMEs of branch 62. A

close comparison of the areas of the internal and

external streams in Figs. 2 and 3 reveals that they are

located in opposing areas. The external boundary of

the internal stream of OIC acquisition in branch 62 is

designated by human capital, innovation capital,

project capital and information capital (Figure 2),

while innovation capital, project capital and relational

capital designate the boundary of the external stream

of OIC acquisition in branch 26 (Figure 3).

Accordingly, the component acquisition of OIC

reveals significant differentiation between the

compared branches.

5 FUTURE RESEARCH

This research was conducted in a new field and

undoubtedly extends the knowledge of OIC

acquisition by enterprises. The presented results

provide the opportunity and indicate the need to

continue research into more detailed topics in the

field of OIC acquisition in other branches. The

continued development of research will allow

comparative analyses of different groups of

enterprises and branches in terms of OIC acquisition.

This can contribute to the development of knowledge

on diversified OIC acquisition by enterprises

characterised by various sizes and who conduct

business in various industries. Continued research

will also improve the methods of comparative

analysis and evaluation of OIC acquisition with the

aim of building an OIC acquisition model.

REFERENCES

Abeysekera, I., 2021. Intellectual Capital and Knowledge

Management Research towards Value Creation. From

the Past to the Future. Journal of Risk Financial

Management. 14(6), DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/jr

fm14060238.

Ahmed, A., Bhatti, S. H., Gölgeci, I., Arslan, A., 2022.

Digital platform capability and organizational agility of

emerging market manufacturing SMEs: The mediating

role of intellectual capital and the moderating role of

environmental dynamism. Technological Forecasting

and Social Change. 177, 121513.

Alimov, A., Officer, M. 2017. Intellectual property rights

and cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Journal of

Corporate Finance, 45, 360-377.

Barney, J.B., Hesterly, W.S., 2019. Strategic Management

and Competitive Advantage. Pearson. Harlow. UK.

Dimitrios, M., Dimitrios, Ch., Charalampos, T., Theriou,

G., 2011. The impact of intellectual capital on firms'

market value and financial performance. Journal of

ICSBT 2022 - 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

78

Intellectual Capital. 12, 132-151, DOI:

10.1108/14691931111097944.

Edvinsson, L., Malone, M.S., 1997. Intellectual Capital:

Realizing Your Company’s True Value by Finding Its

Hidden Brainpower. Harper Business. New York.

European Communities, 2008. Statistical Classification of

Economic Activities in the European Community.

Office for Official Publications of the European

Communities. Luxembourg.

Hatcher, L., 2013. Advanced Statistics in Research.

Shadow Finch Media. Saginaw.

Hejase, H.J., Hejase, A., Assi, H.T., Chalak, H.C., 2016.

Intellectual Capital: An Exploratory Study from

Lebanon. Open Journal of Business and Management.

4, 571-605.

Lee, C., Wong, K., 2019. Advances in Intellectual Capital

Performance Measurement: A State-of-the-art Review.

The Bottom Line. 32(2), 118-134, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-12-2018-0051.

Mačerinskienė, I., Survilaitė, S., 2019. Company’s

Intellectual Capital Impact on Market Value of Baltic

Cuntries Listed Enterprises. Oeconomia Copernicana.

10(2), 309-339, DOI: https://doi.org/10.24136/

oc.2019.016.

Matricano, D., Candelo, E., Sorrentino, M., Cappiello, G.,

2020. Investigating the Link Between Intellectual

Capital and Open Innovation Processes: a Longitudinal

Case Study. Journal of Intellectual Capital. 3

rd

December, DOI:10.1108/jic-02-2020-0020.

McConnell, S., 2019. More Effective Agile: A Roadmap for

Software Leaders. Construx Press. Bellevue.

Nazari, J., 2015. Intellectual Capital Measurement and

Reporting Models. [In:] Knowledge Management for

Competitive Advantage During Economic Crisis,

Ordoñez de Pablos, P., Turró, L.J., Tennyson, R.D.,

Zhao, J. (eds.). IGI Global. Hershey, 117-139, DOI:

10.4018/978-1-4666-6457-9.ch008.

Pike, S., Roos, G., 2000. Intellectual Capital Measurement

and Holistic Value Approach. Works Institute Journal.

42 (October/November), 1-15.

Pulic, A., 2004, Intellectual Capital-Does it Create or

Destroy Value. Measuring Business Excellence. 8(1),

62-68, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/136830404105

24757.

Roos, G., Pike, S., 2018. The Strategic Management of

Intellectual Capital: Essentials for Leaders and

Managers. Routledge. New York.

Santis, S., Binachi, M., Incollingo, A., Bisogno, M., 2019.

Disclosure of Intellectual Capital Components in

Integrated Reporting: An Empirical Analysis.

Sustainability. 11(62), 1-15, DOI: 10.3390/su11010

062.

Schiavone, F., Leone, D., Caporuscio, A., Kumar, A., 2022.

Revealing the role of intellectual capital in digitalized

health networks. A meso‑level analysis for building and

monitoring a KPI dashboard. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change. 175, 121325.

Sharpe, N., Veaux, R., Velleman, P., 2014. Business

statistics. Pearson Publisher. Boston.

Stewart, T.A., 1998. Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth

of Organizations. Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

London.

Sveiby, K., 2001. Methods of Measuring Intangible Assets.

Sveiby Knowledge Associates Publisher, available at:

https://www.sveiby.com/files/pdf/1537275071_metho

ds-intangibleassets.pdf (accessed: Dec, 08, 2021).

Wiederhold, G., 2014. The Value of Intellectual Capital.

Springer. New York, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-

1-4614-6611-6_3.

Yovita, M., Kardina, G., Amrania, P., 2018. The Influence

of Intellectual Capital to Market Value with Return on

Assets as Intervening Variable. Journal of Accounting

Auditing and Business. 1(2), 9-16, DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.24198/jaab.v1i2.18267.

Diversity of Open Intellectual Capital Acquisition by SMEs of Different Branches

79