Breathing Life into Models: The Next Generation of Enterprise Modeling

Peter Fettke

1,2 a

and Wolfgang Reisig

3 b

1

German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI), Saarbr

¨

ucken, Germany

2

Saarland University, Saarbr

¨

ucken, Germany

3

Humboldt-Universit

¨

at zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Keywords:

Systems Composition, Data Modeling, Behaviour Modeling, Process Modeling, Composition Calculus,

Algebraic Specification, Systems Mining.

Abstract:

Edsger W. Dijkstra has frequently suggested building a “firewall” between the technology- and application-

side of computer science. His justification: The methods to attack the computer scientists’ formal, mathemati-

cal “correctness problem” differ fundamentally from the methods to attack the applicants’ informal “pleasant-

ness problem”. In this setting, a model is always confined to one side or the other of this wall. This keynote

shows that a seamless transition between both sides can be achieved by a framework with architecture, statics,

and dynamics as the three pillars of modeling computer-integrated systems. Selected examples justify this

framework. It allows to “breath life” into (static) models, and it implies a new understanding of the “pleasant-

ness” of computer-integrated systems, which is well-needed in the age of “digital first”.

1 INTRODUCTION: THE TWO

FACES OF COMPUTER

SCIENCE

Computer-integrated systems exhibit two faces: the

technological and the applied face. Edsger W. Dijk-

stra has frequently suggested to strictly separate both

sides and to build a “firewall” between them (Dijkstra,

1989). His justification: The methods to attack the

computer scientists’ formal, mathematical “correct-

ness problem” differ fundamentally from the methods

to attack the applicants’ informal “pleasantness prob-

lem”. In this setting, a model is always confined to

one side or the other of this wall.

In contrast to Dijkstra, we understand modeling

as an activity that should allow a seamless transition

between formally and informally given or asserted

facts of a computer-integrated system. Technology

and applications must be interlocked by shared mod-

els, based on the same foundations.

This keynote shows that our goal can be achieved

by the HERAKLIT framework with architecture, stat-

ics, and dynamics as the three pillars of model-

ing computer-integrated systems (Fettke and Reisig,

2021a; Fettke and Reisig, 2021b). Selected examples

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0624-4431

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7026-2810

justify this framework. It allows to “breathe life” into

previous static, logic-based models, and it implies a

new understanding of the “pleasantness” of computer-

integrated systems. This is a key to understanding

systems in the age of “digital first”.

This contribution consists of five sections. After

this introduction, Section 2 explains what is needed

for the foundations of computer-integrated systems

from the application perspective. Section 3 presents

our approach to digital modeling through a plain case

study. Main characteristics of HERAKLIT and related

work are discussed in Section 4 and 5, respectively.

The paper concludes with Section 6.

2 TOWARDS FOUNDATIONS FOR

THE APPLICATION SIDE OF

COMPUTER SCIENCE

In the last decades, computing-oriented disciplines

have developed several strong ideas for the founda-

tions of computer science. Typically, foundations

of computer science stem from technical foundations

such as abstractions of hardware, physical devices,

sensors, actuators, etc. Another approach stems from

theoretical computer science, starting with alphabets,

formal languages, computable functions, etc.

Fettke, P. and Reisig, W.

Breathing Life into Models: The Next Generation of Enterprise Modeling.

DOI: 10.5220/0011376600003266

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Software Technologies (ICSOFT 2022), pages 7-14

ISBN: 978-989-758-588-3; ISSN: 2184-2833

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

7

But what are the foundations from the application-

side of computer science? In this contribution, we

argue that such foundations must cope with three fun-

damental phenomena:

• Architecture: Computer-integrated systems in the

real or an imagined world are not monolithic,

amorphous, or unstructured, but can best be de-

scribed and understood as the composition of dif-

ferent sub-systems. Hence, composing a system is

inevitable for the proper understanding of a com-

plex system. In one sentence: composition mat-

ters!

• Statics: Computer-integrated systems process

data. However, the world we live in consists

not only of symbolic data objects but of many

more relevant objects, e.g. invoices, customers,

agreements, orders, and products. These objects

need to be understood and represented adequately.

Again, in one sentence: objects matter!

• Dynamics: The world is not static, but continu-

ously evolving. Events happen all over the world

in time and space. A system’s progress in time

induces an order of events; however, this order is

irrelevant for a proper understanding of the event

flow. On the contrary, it spoils the causal order of

events, which orders two events a and b by a < b

if and only if a is a prerequisite for b. Of course,

a < b implies each potential clock to timestamp

a before b. But a timestamped before b only im-

plies that b is not a prerequisite for a. Again, in

one sentence: causality matters!

To sum up, composition, objects, and causality

are important for understanding the application side

of computer science. In other words, the world we

are living in matters. In our contribution, we show

that HERAKLIT, an integrated modeling framework

to formally describe the aspects mentioned before, is

indeed feasible.

3 A PLAIN EXAMPLE

The following subsections illustrate the three HER-

AKLIT’s pillars by the plain example of a digital

stamp, a stamp that is augmented with a matrix code.

Fig. 1 depicts one exemplar of a digital stamp; each

digital stamp carries a unique matrix code for individ-

ual identification.

3.1 Architecture

The basic concept of architecture is modules. Inside a

module, HERAKLIT typically uses Petri nets in vari-

Figure 1: Digital stamp with matrix code (right).

ous forms. In general, a module M has two interfaces,

the left interface

∗

M, and the right interface M

∗

. An

interface can contain Petri net places as well as transi-

tions. Graphically, a module is represented as a rect-

angle, with the elements of the left interface on the

left or top edge of the rectangle and the elements of

the right interface on the right or bottom edge.

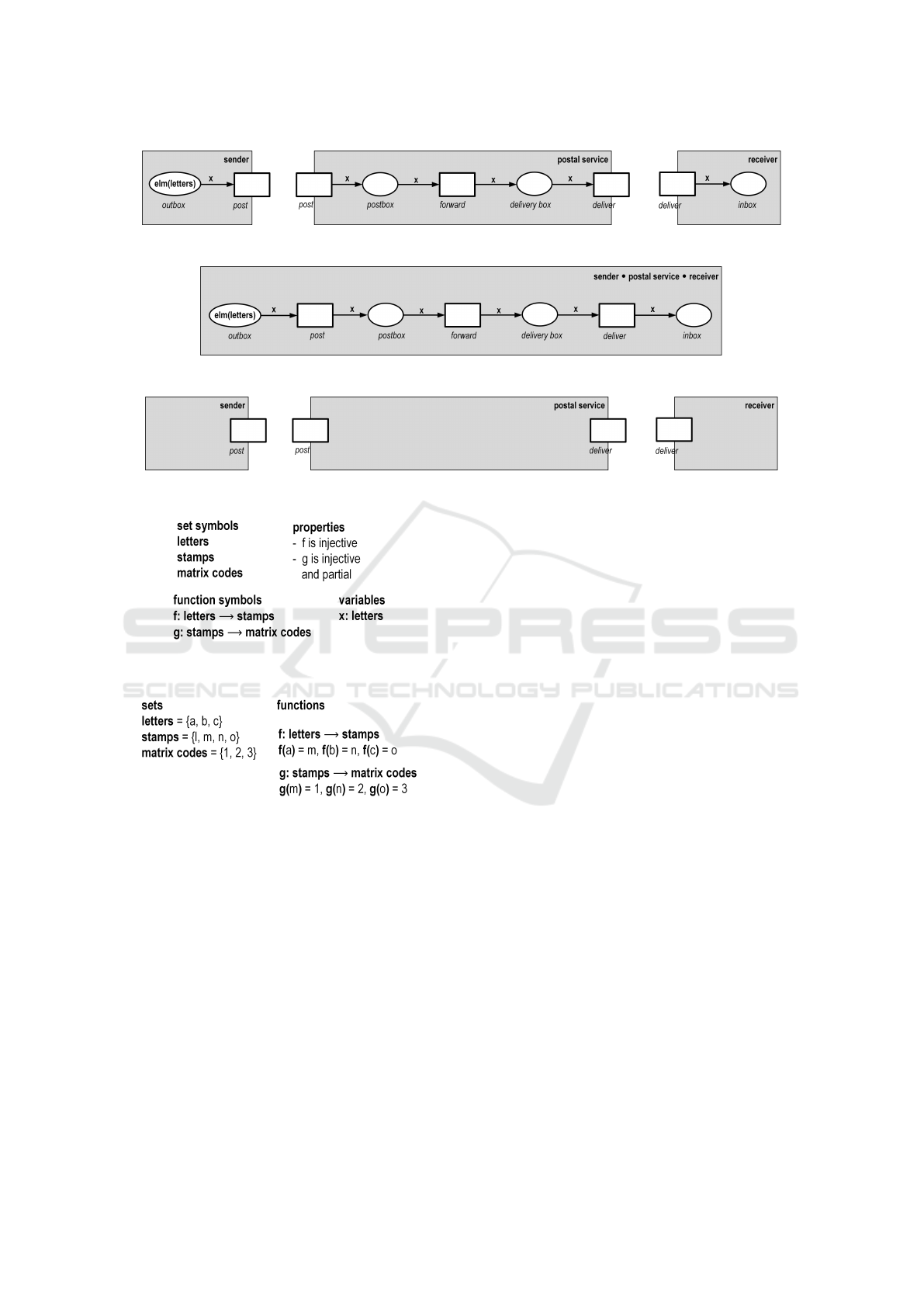

Fig. 2 shows a typical model for the transporta-

tion of conventional letters. There are three modules:

the sender, the postal service, and the receiver. The

left interface of the sender is empty, its right interface

contains a Petri net transition. The label of this tran-

sition, post, matches the labels of the transition of the

left interface of the postal service; transitions with the

same labels are merged later on when the two mod-

ules will be composed. Likewise, the right interface

of the postal service and the left interface of the re-

ceiver contain equally labeled transitions.

The labels of the interface elements indicate the

behavior and functionality of the modules: the sender

posts each letter to the postal service. The postal ser-

vice delivers each letter to the receiver. The receiver

finds the letter in its inbox.

Fig. 3 shows the composition of the three mod-

ules, namely:

sender • postal service • receiver (1)

with “•” being the universal composition opera-

tor. This bracket free notation is possible since the

composition operator is associative, i.e. for any three

models R, S, T holds (Reisig, 2019):

(R • S) • T = R • (S • T ). (2)

The greatest possible abstraction of the modules

is depicted in Fig. 4. Two activities of a postal ser-

vice are modeled: post and deliver a letter; techni-

cally as Petri net transitions in

∗

postal service and

postal service

∗

with the labels post and deliver, re-

spectively.

3.2 Statics

In each postal service, three sets of items play a cen-

tral role: letters, stamps, and matrix codes. In a

postal service, these quantities consists of different

elements: each postal service has different sets of let-

ters, stamps, and matrix codes.

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

8

Figure 2: Three modules: sender, postal service, and receiver.

Figure 3: The composition sender • postal service • receiver.

Figure 4: The abstract form of the three modules sender, postal service, and receiver.

Figure 5: Signature Σ

0

.

Figure 6: Σ-structure S

0

.

Nevertheless, to formulate the processes for all

postal services in the same way, we use a signature,

Σ

0

, shown in Fig. 5, a technique to model a schema.

This technique allows to characterize concrete objects

from the real and imagined world as instantiations of

such a schema. Here, we adopt notions such as struc-

tures, signatures, and instantiations of signatures, that

are well-known from first-order logic (Suppes, 1957).

Technically, a signature is just a set of sorted sym-

bols for sets, constants, and functions. An instantia-

tion interprets these symbols consistently. We extend

signatures by requirements to exclude “unwanted” in-

stantiations.

In the example, the signature contains the three

symbols letters, stamps, and matrix codes for the

three sets described above, plus two symbols ( f and

g) for functions. The symbol f stands for a function

that assigns to each letter its stamp; g for a function

that assigns to each stamp its matrix code. Both func-

tions are injective. The function symbol g stands for

a function that is only partially defined since some

stamps do not carry a matrix code.

The signature Σ

0

can be instantiated in many

ways. Each concrete postal service is characterized

by such an instantiation of the signature. In the case

study, we discuss the instantiation S

0

of Fig. 6. This

instantiation consists of three letters (a, b, c), four

stamps (l, m, n, o), three matrix codes (1, 2, 3), and

a particular assignment between letters, stamps, and

matrix codes. For example, letter a is assigned to

stamp m; stamp m is assigned to matrix code 1.

3.3 The Behavior of the Three Modules

at the Schema Level

Signatures and their instantiations can naturally be

transferred to define Petri net schemata. Such a sche-

ma can be instantiated in different ways; each instan-

tiation results in a concrete Petri net.

We model the behavior of each of the three mod-

ules from Fig. 2. Fig. 3 shows the behavior of each

module at the schema level, i.e. based on the signature

Σ

0

, rather than a single instantiation. As a mathemat-

ical concept, a place represents a predicate that ap-

plies to a set of objects. This set can grow and shrink

through the entry of transitions.

The sender module in Fig. 2 describes the letters to

be sent. The question of an appropriate initial mark-

ing arises: for a given instantiation, i.e. a concrete

Breathing Life into Models: The Next Generation of Enterprise Modeling

9

postal service, the place outbox initially contains all

letters as tokens. In the example of the structure S

0

from Fig. 6, these are the three tokens a, b, and c.

On the schematic level, we only know the symbol let-

ters, for which each instantiation can freely choose an

assignment with a set of letters. However, the intu-

itively obvious idea of labeling the place outbox with

the symbol “letters” falls short: when instantiating

the symbol letters with a set, for example {a, b, c},

initially this set would emerge as a single token. How-

ever, we want the three elements of this set as individ-

ual tokens. This is noted as “elm(letters)”.

Mathematically, the idea behind this is that a place

represents a predicate that currently applies to the to-

kens on the place. The place outbox with the inscrip-

tion elm(letters) thus stands for the logical expression:

∀x ∈ letters : outbox(x). (3)

The instantiation S

0

thus generates in the ini-

tial marking the logical expression ∀x ∈ {a, b, c} :

outbox(x). Thus, initially, the three tokens a, b, c lie

on the place outbox.

In a given instantiation S

0

, the transition post can

occur in the sender or postal service module as soon

as a token is present on the place outbox. The assign-

ment of the variable x can freely be chosen from the

set with which the instantiation S

0

instantiates the set

symbol letters. In analogy, the postal service module

forwards one letter from the postbox to the delivery

box. Finally, the letter is delivered to the receiver.

3.4 The Instantiation S

0

and its

Behavior

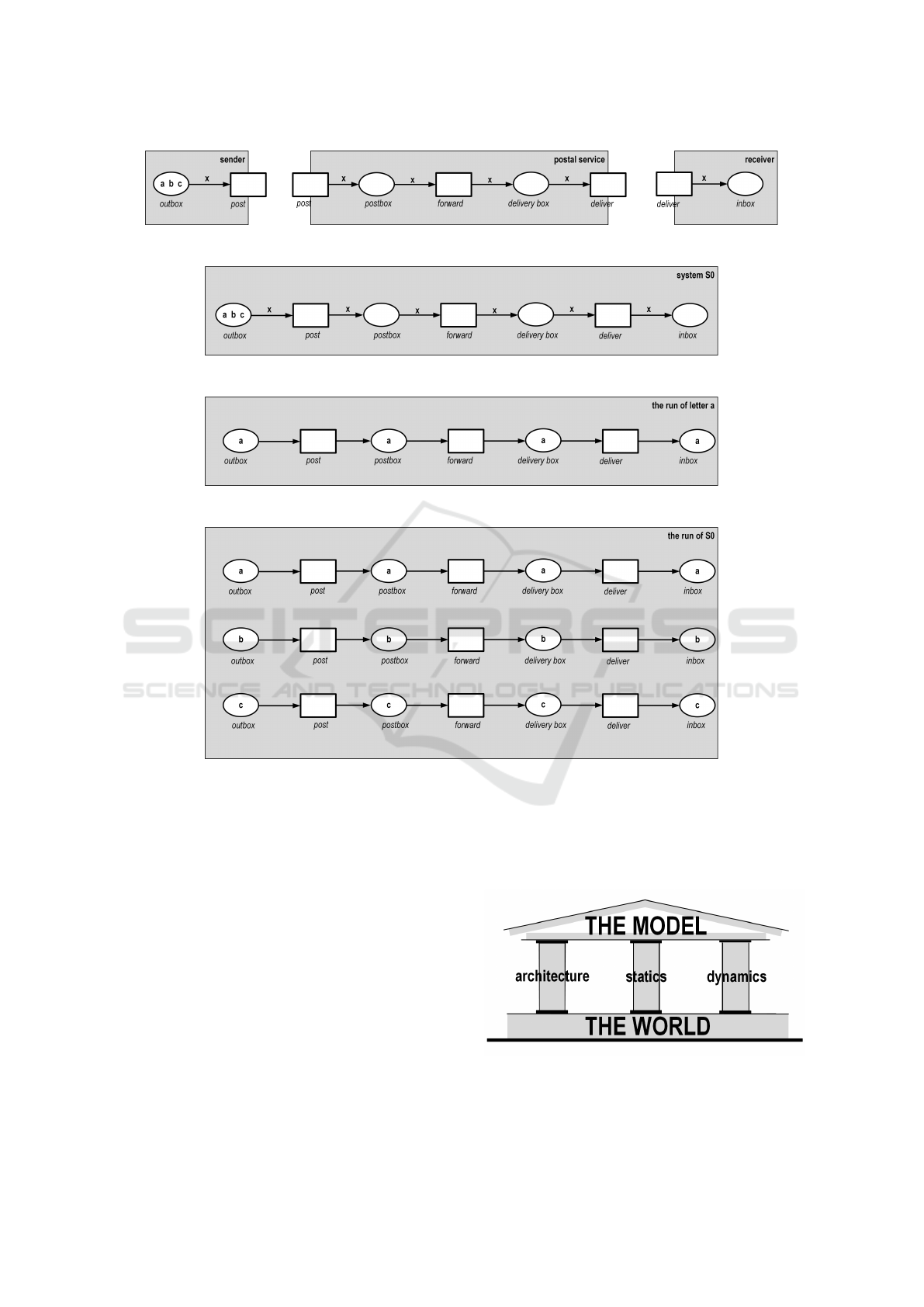

Fig. 7 shows three instantiated modules; Fig. 8 shows

the module system S

0

, which is created from the mod-

ules of Fig. 2 in two steps: first, the three modules

from Fig. 2 are composed into a single module, and

second, the signature Σ

0

of Fig. 5 is instantiated with

the structure S

0

of Fig. 6. In particular, the place out-

box now contains three tokens.

In the instantiation S

0

, one can now document the

processing of individual postal services. In the ini-

tial state, for example, the transition post is activated.

After that, the letter can be posted by the sender, for-

warded to the delivery box, and be delivered to the

receiver.

HERAKLIT models a behavior as a distributed run;

formally conceived as a module. This makes it easy to

compose distributed runs. The current example also

shows that distributed runs show details of behavior

much more explicitly than is possible with sequential

runs. In particular, relationships between objects and

causality is explicitly modeled.

Fig. 9 shows what happens with the letter a: The

letter moves from the sender’s outbox to the postbox,

then to the delivery box and finally to the receiver’s

inbox. Technically, this is the run of letter a in the

system S

0

. Fig. 8 depicts two more letters, b and c,

yielding corresponding runs. Together, the three runs

of a, b, and c define the overall run of the system

S

0

, shown in Fig. 10. In the run of each single letter,

the events post, forward and deliver occur strictly or-

dered. As the letters proceed independently of each

other, the events of different letters occur indepen-

dently, namely their occurrences are not ordered in

the overall run of the system S

0

.

Fig. 10 exemplifies that events are not ordered

along a time axis; instead, order represents causal-

ity. For example, the event forward for letter a oc-

curs causally after the event post for letter a, but is

causally independent from all events of the letters b

and c. The run of Fig. 10 is the only run of the sys-

tem S

0

in Fig. 8. System S

0

is deterministic, as there

is never a decision to be taken; and S

0

is concurrent,

as some events occur unordered. One may neverthe-

less introduce global views into the run of Fig. 10.

A global view is a maximal set of unordered places.

Each of the three letters can be in exactly one of the

four boxes. In technical terms, each such set corre-

sponds to one of the 64 (= 4 ×4 ×4) reachable mark-

ings of the system in Fig. 8.

4 MAIN CHARACTERISTICS OF

HERAKLIT

The main characteristics of the HERAKLIT frame-

work were introduced by means of a plain exam-

ple. From a conceptual point of view, the HERAK-

LIT framework is based on three pillars (Fettke and

Reisig, 2021a; Fettke and Reisig, 2021b). Each pillar

focuses on different but integrated aspects of model-

ing (Fig. 11):

• Architecture: A HERAKLIT model consists of

modules. Each module has an arbitrarily designed

interior; in particular, the level of abstraction of

the representation is freely selectable. The inter-

face of a module contains labeled elements. The

composition of modules is technically simple and

always associative. The formal basis of this ar-

chitectural principle is the composition calculus

(Reisig, 2019).

• Statics: For dealing with data and data structures,

HERAKLIT employs abstract data types and al-

gebraic specifications, as they have turned out to

be useful in computer science from the begin-

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

10

Figure 7: Three instantiated modules.

Figure 8: System S

0

.

Figure 9: The run of letter a.

Figure 10: The run of S

0

.

ning and have long been used in specification lan-

guages such as V DM, Z, etc. (Sanella and Tar-

lecki, 2012). Symbolic representations (in terms

of a signature) are used as in predicate logic. Each

module has a signature, i.e. a set of symbols for

sets, constants, and functions, from which, to-

gether with variables, terms are then formed. A

signature, and thus its terms, can be instantiated

in quite different ways.

• Dynamics: A module for describing behavior

contains a Petri net inside of it. Here, each place

of the Petri net is a logical predicate, each arrow

is labeled with a term of the module’s signature,

and each transition with a condition. For a given

instantiation of the signature, the set of objects

to which the predicate applies can grow or shrink

due to the occurrence of an event. In detail, this

is described by terms at the arrows of the Petri

net. This allows behavior to be represented ab-

stractly on a schematic level, but also concretely

for a “meant” instantiation.

Figure 11: The three pillars of HERAKLIT.

Breathing Life into Models: The Next Generation of Enterprise Modeling

11

5 RELATED WORK

In the last decades, a plethora of modeling frame-

works emerged (Frank et al., 2014; Sandkuhl et al.,

2018; Vernadate, 2020; Wand and Weber, 2002).

In 1992 already, some colleagues coined the term

“methodology jungle” for characterizing the variety

and diversity of the research field (ter Hofstede and

van der Heide, 1992). Nowadays, this field is still

evolving and maturing. Relevant work can be ap-

proached from different angles, e.g. the problem ad-

dressed or the solution purported.

In the field of business informatics, typical frame-

works used are Architecture for Integrated Informa-

tion Systems (ARIS) (Scheer, 1999), Business Process

Model and Notation (BPMN) (Object Management

Group, 2014), Event-Driven Process Chains (EPC)

(Keller et al., 1992), MEMO (Frank, 2014), the St.

Gallen Approach to Business Engineering (

¨

Osterle,

1995; Winter, 2001), and Unified Modeling Language

(UML) (Object Management Group, 2017). Most

of them offer graphical representations to describe

behavior (e.g. BPMN, EPC), some have expressive

means for data structures (e.g. ARIS, MEMO), and in

some cases also for schemas (MEMO). Some known

frameworks use more or less formally defined com-

position operations. None of the frameworks are fully

formally defined but describe many aspects only intu-

itively. Thus, no other framework reaches the scope

of expressive means of HERAKLIT. This characteri-

zation is also true for frameworks stemming from the

information systems discipline, e.g. Bunge’s ontolog-

ical model (Wand and Weber, 1990) or work system

theory (Alter, 2013).

From a computer science perspective, several

modeling frameworks were proposed, e.g. Abstract

State Machines (ASM) (Gurevich, 2000), Aloy (Jack-

son, 1987), High-level Petri Nets (Genrich and Laut-

enbach, 1981; Jensen and Kristensen, 2009), event-

B (Abrial, 2005), FOCUS (Broy, 1997; Broy and

Stolen, 2001), Statecharts (Harel, 1987), TLA (Lam-

port, 2002), and Z (Spivey, 1992). The central

ideas and concepts of HERAKLIT combine three well-

proven, intuitively easy to understand, and mathe-

matically sound concepts that have been used for the

specification of systems in the past:

• Architecture: The composition calculus for struc-

turing large systems. This calculus with its widely

applicable associative composition operator is the

most recent contribution to the foundations of

HERAKLIT. The obvious idea, often discussed in

literature, of modeling composition as fusion of

equally labeled interface elements of modules is

supplemented by the distinction of left and right

interface elements, and composition A • B as fu-

sion of right interface elements of A with left

interface elements of B. According to (Reisig,

2019), this composition is associative (as opposed

to the naive fusion of interface elements); it also

has several other useful properties. In particu-

lar, the composition is compatible with refinement

and with single (distributed) runs.

• Statics: Abstract data types and algebraic spec-

ifications for the formulation of concrete and

abstract data: since the 1970s such specifica-

tions have been utilized, built into specification

languages, and often used for (domain-specific)

modeling. (Sanella and Tarlecki, 2012) presents

systematically the theoretical foundations and

some applications of algebraic specifications.

• Dynamics: Petri nets for formulating dynamic be-

havior: HERAKLIT uses the central ideas of Petri

nets (Petri, 1962; Reisig, 2013). A step of a sys-

tem, especially of a large system, has locally lim-

ited causes and effects (Petri, 1977). This allows

processes to be described without having to use

global states and globally effective steps. The

connection with algebraic specifications is estab-

lished by (Reisig, 1991).

These three theoretical principles harmonize to-

gether and generate further best-practice concepts that

contribute to a methodical approach of modeling with

HERAKLIT and which could only be touched upon in

this keynote. On the downside, industrially mature

tools for HERAKLIT are still under development.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The fundamental focus of our approach becomes clear

in comparison with the firewall propagated by Dijk-

skra: HERAKLIT follows the tradition of logic, inte-

grating formal arguments as part of the scientific pen-

etration of real-life facts. Logic has successfully been

doing this for 2000 years. HERAKLIT extends for-

mal logic by including dynamic aspects, and shapes a

connection between informal and formal concepts.

Like no other framework, HERAKLIT combines

the three pillars of architecture, statics, and dynam-

ics for modeling computer-integrated systems. For-

mulated in buzzword form on a technical level:

HERAKLIT =

modules + relational structures + local steps,

and on the level of calculi:

HERAKLIT =

composition calculus + logic + Petri nets.

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

12

With HERAKLIT, both sides of Dijskrta’s wall can

be grounded on the same foundations. It is obvious

that this approach has decisive advantages and will

achieve tremendous gains: It is seamlessly possible

to capture the main ideas of a natural and intuitive

understanding of the world we live in, enrich this

understanding with formal concepts, and use the de-

scription as a foundation for (forthcoming) supporting

software.

The technical HERAKLIT concepts described can

be used to model aspects of discrete systems in a way

that no other modeling technique can:

• Modules of different hierarchical levels can be

composed, e.g. a module may represent the be-

havior of a component at the finest, operational

level. At the same time, its neighboring modules

are given only by their names and their interface.

• Real-world and abstract objects are coequal ele-

ments of formal reasoning. HERAKLIT follows

predicate logic and conceives both, real-world and

formal objects, as interpretations of terms of a sig-

nature (an alphabet with typed symbols).

• Behavioral models can be parameterized. Each

interpretation of the symbolic labels of a

schematic HERAKLIT module generates a sepa-

rate system model. For example, a schematic

module describes the principles of business pro-

cesses of all branches of a commercial bank; each

interpretation describes a concrete branch.

• The size of models grows linearly with the size

of systems. This is especially true for model-

ing dynamic behavior. To achieve this, HERAK-

LIT works without globally effective constructs,

in particular without global states. The notion of

single runs, as well as the composition operator

for modules, are likewise locally confined.

• HERAKLIT adopts verification techniques. Petri

nets provide a variety of efficient computational

verification techniques. The most important ones,

in particular place- and transition invariants, also

work at the symbolic (signature) level and – more

expressively – for individual interpretations of a

signature. Verification based on model check-

ing is only possible for individual interpretations

of a signature; efficient procedures exist for this.

A large, still open research area is compositional

verification: properties of a composed system are

derived from properties of the composed modules.

• A single run can be distributed. In a run of a

system, events often occur independently. For

example, in a bank branch, employees interact

with individual customers largely independently;

they are only occasionally synchronized when ac-

cessing scarce resources, such as meeting rooms.

Many modeling frameworks model this kind of

independent events as “occurence in any order” .

This leads to exponentially many supposedly dif-

ferent “sequential” processes. HERAKLIT explic-

itly models independence of events, not only in

sequences but any other partial order. This yields

a clear notion of non-determinism and a theorem

according to which the runs of a composed system

are derivable from the runs of its components.

• HERAKLIT uses intuitively simple basic concepts:

predicate logic is familiar to many users from

other contexts anyway. Petri nets are also widely

used in computer science and its application areas.

The composition calculus is immediately conceiv-

able from small examples. The graphical means

of expression of Petri nets and the composition

calculus complement each other harmoniously.

It is plausible that HERAKLIT will help to har-

monize the plethora of different phenomena asso-

ciated with computer-integrated systems. In other

words, it will be possible to describe the essence

of different application types, and system structures

of applications, including real-time systems, reac-

tive systems, data-intensive systems, cyber-physical

systems, service-based systems, integrated business

systems for enterprise resource planning (“ERP sys-

tems”), supply chain management (“SCM systems”),

customer relationship (“CRM systems”, “ticket sys-

tems”), product lifecycle management (“PLM sys-

tems), and many more system types in the “digital

world”.

In the future, more work is needed to develop the

HERAKLIT framework into a universal modeling in-

frastructure:

1. More case studies and industrial applications are

required, to identify special classes of models,

shorthands, best practices, etc.

2. HERAKLIT specific analysis methods have to be

developed, respecting and employing the local

character of events and modules, to formulate and

to prove decisive properties of models.

3. Powerful software tools have to be created, sup-

porting the construction of models, their analysis,

the integration of databases, etc.

So far, HERAKLIT provides fundamental pillars

for systematically developed, theory-based models,

covering a broader spectrum of aspects than any other

modeling infrastructure. It is now time to “breathe

life” into models with HERAKLIT.

Breathing Life into Models: The Next Generation of Enterprise Modeling

13

REFERENCES

Abrial, J.-R. (2005). The B-Book – Assigning Programs to

Meanings. Cambridge University.

Alter, S. (2013). Work system theory: Overview of core

concepts, extensions, and challenges for the future.

Journal of the Association for Information Systems,

14(2).

Broy, M. (1997). Compositional refinement of interactive

systems. Journal of the ACM, 44(6):850–891.

Broy, M. and Stolen, K. (2001). Specification and Develop-

ment of Interactive Systems: Focus on Streams, Inter-

faces, and Refinement. Springer.

Dijkstra, E. W. (1989). Reply to comments. Commun. ACM,

32(12):1414.

Fettke, P. and Reisig, W. (2021a). Handbook of HERAKLIT.

HERAKLIT working paper, v1.1, September 20, 2021,

http://www.heraklit.org.

Fettke, P. and Reisig, W. (2021b). Modelling service-

oriented systems and cloud services with HERAK-

LIT. In Zirpins, C., Paraskakis, I., Andrikopoulos, V.,

Kratzke, N., Pahl, C., El Ioini, N., Andreou, A. S.,

Feuerlicht, G., Lamersdorf, W., Ortiz, G., Van den

Heuvel, W.-J., Soldani, J., Villari, M., Casale, G., and

Plebani, P., editors, Advances in Service-Oriented and

Cloud Computing, pages 77–89, Cham. Springer In-

ternational Publishing.

Frank, U. (2014). Multi-perspective enterprise modeling:

foundational concepts, prospects and future research

challenges. Journal of the Association for Information

Systems, 13(2):941–962.

Frank, U., Strecker, S., Fettke, P., vom Brocke, J., Becker,

J., and Sinz, E. J. (2014). The research field ”mod-

eling business information systems“ – current chal-

lenges and elements of a future research agenda. Busi-

ness & Information Systems Engineering, 6(1):39–43.

Genrich, H. J. and Lautenbach, K. (1981). System mod-

elling with high-level petri nets. Theoretical Com-

puter Science, 13:109–135.

Gurevich, Y. (2000). Sequential abstract-state machines

capture sequential algorithms. ACM Transactions on

Computational Logic, 1:77–111.

Harel, D. (1987). Statecharts: A visual formalism for com-

plex systems. Science of Computer Programming,

8(3):231–274.

Jackson, D. (1987). Alloy: A language and tool for explor-

ing software designs. Communications of the ACM,

62(9):66–76.

Jensen, K. and Kristensen, L. M. (2009). Coloured Petri

Nets: Modelling and Validation of Concurrent Sys-

tems. Springer.

Keller, G., N

¨

uttgens, M., and Scheer, A.-W. (1992).

Semantische Prozeßmodellierung auf der Grundlage

Ereignisgesteuerter Prozeßketten (EPK). Techni-

cal Report 89, Ver

¨

offentlichungen des Instituts f

¨

ur

Wirtschaftsinformatik (IWi) an der Universit

¨

at des

Saarlandes.

Lamport, L. (2002). Specifying Systems: The TLA+ Lan-

guage and Tools for Hardware and Software Engi-

neers. Adison-Wesley.

Object Management Group (2014). Business process model

and notation (bpmn): Version 2.0.2. Technical Report

formal/2013-12-09, Object Management Group.

Object Management Group (2017). Omg unified modeling

language (omg uml): Version 2.5.1. Technical Report

formal/2017-12-05, Object Management Group.

Petri, C. A. (1962). Kommunikation mit Automaten. PhD

thesis, Institut f

¨

ur instrumentelle Mathematik der Uni-

versit

¨

at Bonn.

Petri, C. A. (1977). Non-sequential processes. Techni-

cal Report ISF-77-5, Gesellschaft f

¨

ur Mathematik und

Datenverarbeitung, St. Augustin, Federal Republic of

Germany.

Reisig, W. (1991). Petri nets and algebraic specifications.

Theoretical Computer Science, 80:1–34.

Reisig, W. (2013). Understanding Petri Nets. Springer.

Reisig, W. (2019). Associative composition of compo-

nents with double-sided interfaces. Acta Informatica,

56(3):229–253.

Sandkuhl, K., Fill, H.-G., Hoppenbrouwers, S., Krogstie,

J., Leue, A., Matthes, F., Opdahl, A., Schwabe, G.,

Uludag, O., and Winter, R. (2018). From expert dis-

cipline to common practice: A vision and research

agenda for extending the reach of enterprise mod-

elling, business and information systems engineer-

ing. Business and Information Systems Engineering,

60(1):69–80.

Sanella, D. and Tarlecki, A. (2012). Foundations of Al-

gebraic Specification and Formal Software Develop-

ment. Springer.

Scheer, A.-W. (1999). ARIS – Business Process Frame-

works. Springer, 3 edition.

Spivey, J. M. (1992). The Z Notation: A reference manual.

Prentice Hall, 2 edition.

¨

Osterle, H. (1995). Business in the Information Age – Head-

ing for New Processes. Springer.

Suppes, P. (1957). Introduction to Logic. Van Nostrand

Reinhold.

ter Hofstede, A. H. M. and van der Heide, T. P. (1992). For-

malization of techniques: chopping down the method-

ology jungle. Information and Software Technology,

34(1):57–65.

Vernadate, F. (2020). Enterprise modelling: Research re-

view and outlook. Computers in Industry, 122:57–65.

Wand, Y. and Weber, R. (1990). An ontological model of

an information system. Transaction on Software En-

gineering, 16(11):1282–1292.

Wand, Y. and Weber, R. (2002). Research commen-

tary: Information systems and conceptual modeling–

a research agenda. Information Systems Research,

13(4):363–376.

Winter, R. (2001). Working for e-business – the business

engineering approach. International Journal of Busi-

ness Studies, 9(1):101–117.

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

14