Customer Need-based Product Positioning for Disruptive Innovations

Günther Schuh

1

, Tim Wetterney

2

and Florian Vogt

2

1

Laboratory for Machine Tools Production Engineering (WZL) RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany

2

Fraunhofer-Institute for Production, Technology IPT, Aachen, Germany

Keywords: disruptive innovations; market segmentation; customer needs; cluster analysis; product positioning.

Abstract: Developing disruptive innovations is still a daunting tasks for established companies. They are unmatched in

creating sustaining innovations, but when it comes to highly innovative products, the success score of most

corporates still lacks market-changing innovations. Incumbents’ New Product Development (NPD) failure

rates of ~40% most of all indicate an insufficient product-market-fit. Studies on disruptive innovations show

that disruption is a continuous process that starts with introducing products in niche markets – defined as

customers with a similar set of needs – from where they gain market share step-by-step. The problem is that

popular market segmentation approaches are not suitable to group customers with a similar need-set and,

hence, make it difficult if not impossible to define products with a great product-market-fit. In this paper, the

authors present a decision model for a need-based product positioning approach. For this, an integrative

framework is presented that connects the three object layers customer needs, market segments and product

positioning in a holistic manner. The decision model will help companies to align product attribute positioning

and customer needs more systematically in context of disruptive innovations – a starting point to increase new

product success.

1 INTRODUCTION

Across industries many companies are confronted

with a commoditization of their product base and a

growing dynamic in their established markets – most

often resulting in incumbents loosing market shares

to new entrants (Christensen, 2015). As a result,

companies increasingly try to avoid growing

competition by either targeting new customer groups

in existing markets or opening up entirely new

markets (Kim and Mauborgne, 2016; King and Tucci,

2002 ). Long-term successful companies such as

Procter&Gamble or Microsoft continuously open

new markets before competitors do – even if it means

cannibalizing current assets in order to profit from

future business (Tellis, 2006). If new competitors

with new products change an existing market

structure permanently at the expense of established

companies, this is called disruption (Yu and Hang,

2010; Sood and Tellis, 2011; Christensen et al, 2015

). Companies across industries are striving to secure

and expand their competitive position by introducing

new products with a disruptive character on their own

before new or existing competitors do (Hang,

Garnsey, and Ruan, 2015; Yu and Hang, 2011;

Schmidt and Druehl, 2008 ). Yet, the task of

introducing new products to new, normally small

niche markets is most often not very successful (Yu

and Hang, 2010): depending on the industry, the new

product failure rate varies between 35-49%

(Castellion and Markham, 2013). As a consequence,

companies are hesitant to allocate resources for

radically new, potentially disruptive projects and,

instead focus on topics with a higher success rate –

mostly being incremental innovations (Reinhardt and

Gurtner, 2011).

The high NPD failure rate is somewhat surprising

considering that incumbents’ products are often

technologically superior and, yet, only manage to

acquire low market acceptance (Chiesa and Frattini,

2014; Talke and Snelders, 2013). With regard to

CHRISTENSEN, one of the key reasons for this high

failure rate is that companies are often following a

one-size-fits-all approach, resulting in products that

are not entirely fulfilling customers' actual needs

(Christensen et al, 2007).The reason for this is that

the customer needs within defined market segments

often highly vary, making the definition of product

features that resonate with the customers’ needs very

difficult. While established market segmentation

300

Schuh, G., Wetterney, T. and Vogt, F.

Customer Need-based Product Positioning for Disruptive Innovations.

DOI: 10.5220/0010308100003051

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies (CESIT 2020), pages 300-307

ISBN: 978-989-758-501-2

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

methods create segments, which are homogeneous

regarding the underlying demographic, regional or

behavioral segmentation criteria, the actual needs of

the customers within those segments can hugely

differ. (Ulwick and Osterwalder, 2016) Hence,

defining products with a good product-market-fit for

these segments is very difficult.

Addressing this issue, the paper aims for

developing a customer needs-based product

positioning approach. For this, an integrative

framework is created that connects the three object

layers customer needs, market segments and product

positioning in a holistic manner. By describing

customers based on their needs using mathematical

vector models, similarity-identifying algorithms can

be applied in order to create homogeneous need

clusters. As these clusters are not yet targetable by

standard marketing instruments, a cross-tabulation of

these clusters with standard segmentation criteria

ensures that these customers can be addressed with

suitable marketing tools. Last, a decision model for

positioning product attributes relatively to a market

segments’ need profile is presented.

Chapter I discusses the general necessity of laying

the groundwork of developing a method to create

similarity-based customer clusters in order to derive

homogeneous market segments and respective

product value propositions. Then, the theoretical

background of customer needs, market segmentation

and product positioning is outlined in chapter II.

Subsequently, chapter III summarizes deficits of the

current state of research considering product

positioning approaches. Based on the previous

chapters, in Chapter IV a method for a need-based

product positioning is presented. The conclusion and

explanation of future research demand in chapter V

complete the paper.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

In the following, a short explanation and definition of

some key elements within this paper are provided for

an easier understanding of the methodology presented

in chapter IV.

2.1 Customer Needs

Across disciplines such as product development,

psychology, business administration or economics

there is no universal definition to describe what users

want. POHLMEYER states that terms such as

attributes, wants, values, jobs, requirements, wishes,

needs, demands, characteristics or wants are used

interchangeably in literature. (Pohlmeyer). However,

what can be differentiated is in how far these terms

are of generic nature versus directed to specific

objects. KOTLER defines needs as basic human

requirements such as needs for food, air or safety .

Needs turn into wants when they are directed to

specific products such as – for the example food – a

cheeseburger or a cake. (Kotler and Keller, 2012)

Since the customer clustering serves as starting point

for the definition of disruptive products that so far are

non -existing, a non-product specific definition is

more suitable. Thus, in the following the term

customer needs shall generally describe

“opportunities to deliver a benefit to a customer”.

Following ULWICK these needs can be of functional

or emotional nature, addressing either psychological

or social needs (e.g. feeling appreciated) versus more

practical ones (e.g. cleaning the apartment) (Ulwick

and Osterwalder, 2016) Generic needs such as need

for comfort or safety are referred to as basic needs in

the following. In contrast, product attributes are

physical or digital solutions in order to address those

needs (Pohlmeyer).

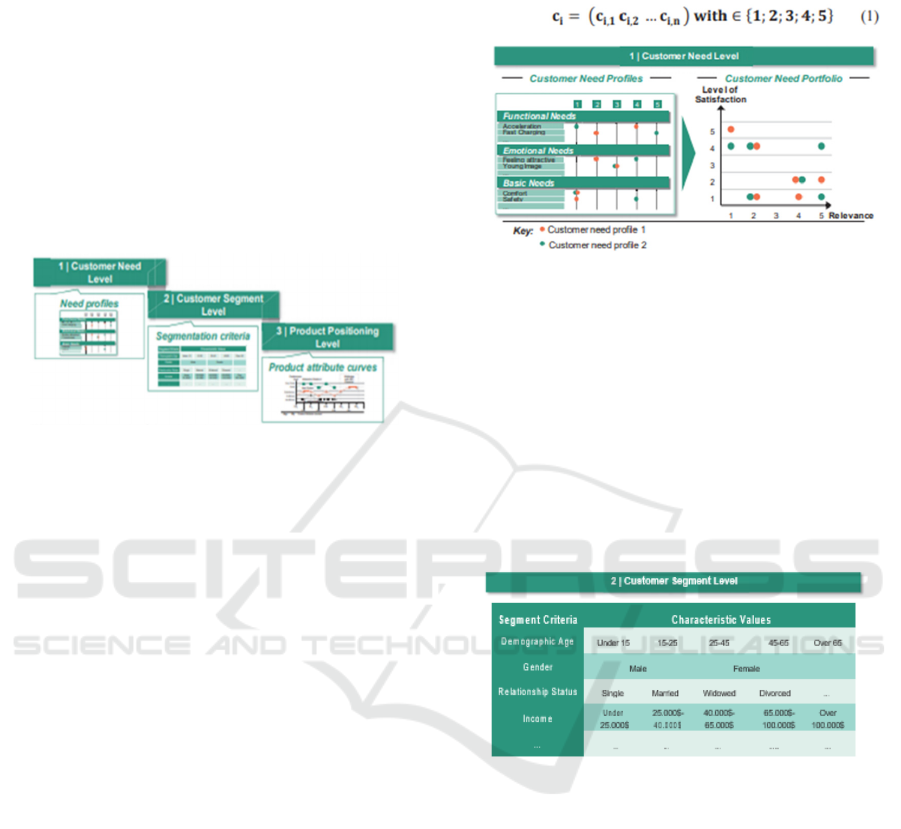

Figure 1: Types of customer needs and product attributes

2.2 Market Segmentation

There are varying definitions on how markets can be

defined, i.e. definitions that concentrate on the goods

that are traded – product- and industry markets – or

definitions separating between real and virtual

markets (Froböse and Thurm, 2016; Kotler et al,

2011). From a marketers’ perspective ‘the providers

of goods and services form an industry and the

(prospective) buyers represent the market’ (Kotler et

al, 2011). This customer-centric market

understanding is also referred to as sales market

(Froböse and Thurm, 2016) and shall apply for this

paper as it puts the customer and his needs in focus.

In the context of disruptive innovations, in general

one specific market niche is addressed with a specific

product strategy (Yu and Hang, 2010). Market niches

are also called segments. A market segment consists

of a group of customers that share similar

Customer Need-based Product Positioning for Disruptive Innovations

301

characteristics (Kotler and Keller, 2012). Segments

are defined based on different segmentation criteria.

Most often, criteria for segmentation are – among

others – demographic, geographic or socioeconomic.

By describing segments with these criteria they

become targetable with different marketing mix

instruments (Aumayr, 2016; Meffert et al, 2019).

ULWICK criticizes the former mentioned criteria,

stating that customer needs might be identical across

several of those segments (Ulwick and Osterwalder,

2016). This criticism also motivates the overall

objective of this paper which is grouping customers

based on their needs to form more homogeneous

groups.

2.3 Product Positioning

Product Positioning describes the position of a

product within the perception space of a customer

(Meffert et al, 2019; Herrmann and Huber, 2013). The

perception space is defined as the key performance

criteria (needs) that are relevant for the customers

when evaluating a product (Bruhn, 2016). Positioning

a product is conducted in comparison to competitor

products and is successful if – from the customers

perspective – the products’ perceived value is

superior to that of the competitor products (Aumayr,

2016). Hence, the product positioning is the core

activity when it comes to creating a great product-

market-fit.

3 RELATED WORK

Section III analyzes different product positioning

approaches. For their evaluation, the subsequent

criteria– derived in previous research papers of the

authors (Schuh et a, 2018; Schuh et al, 2018) – are

taken into account: integrative consideration of

customer needs, market segments and product

positioning; product positioning on a product

attribute level; consideration of disruptive innovation

characteristics.

There are existing approaches that analyze

customer requirements, benefits or wants in order to

derive homogeneous customer segments (Tsai et al,

2015; Machauer and Morgner, 2001; Du, Jiao, and

Tseng, 2003). Also, there are various methods

focusing on matching customer requirements with

suitable product positioning strategies on a brand

level (Gursoy et al, 2005; Arora, 2006; Ibrahim and

Gill, 2005). Last, some authors derive product

designs on a product attribute and functional level

based on their requirements (McAdams et al, 1999;

Yang and Yang, 2011; Borgianni et al, 2012). Yet,

none of the above-mentioned approaches holistically

considers and integrates the need-, segment- and

product positioning-level.

Some authors describe product strategies that

focus on differentiating their value proposition from

competitor products (Kim and Mauborgne, 2016;

Yang and Yang, 2011; Borgianni et al, 2012). Yet, the

strategies in order to position these products are not

defined in context of the specific characteristics of

disruptive innovations. Focusing on the latter,

different authors define characteristics of disruptive

innovations that support market diffusion and

customer adoption (Slater and Mohr, 2006; Kassicieh

et al, 2002; Rueda et al, 2008; Sandberg 2008). But,

these characteristics, e.g. relative advantage,

compatibility, low complexity (Rogers, 2003), are

very generic and not suitable to successfully position

a product relative to competitor products.

In total, the existing approaches do not fulfill the

criteria for a need-based product positioning method

for disruptive products. Either, there is no consistent

approach that step-by-step derives market segments

based on customer needs which again could be used

to specifically position products. Or, the existing

product positioning strategies are formulated on a

brand level and, thus, are too generic. Last, the few

methods, which allow product positioning on a

product attribute level, do not consider the specifics

of disruptive innovations.

4 METHODOLOGY

In order to explain the developed methodology, this

chapter is structured as follows: First, the underlying

framework consisting of the three layers customer

needs,customer segments and product positioning is

explained. Afterwards, an approach to describe

customers based on their needs is introduced. Using

this description model, a way to define customer need

clusters based on a clustering algorithm is presented.

The fourth parts deals with transforming the customer

need clusters into addressable market segments. Last,

it is shown how product attributes can be derived

based on the identified customer needs considering

requirements of disruptive innovations.

4.1 Methodological Framework

The framework is derived from KOTLER’S generic

market segmentation approach and is built upon the

three elements customer needs, market segments and

segment positioning (Kotler and Keller, 2012). The

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

302

first level of the framework describes customers

based on their needs to solve a specific consumption

problem, laying the fundamentals to create a

successful product-market-fit. In order to be able to

address customers with traditional marketing tools,

customers have to be targetable. For this, on the

second level customer segments are defined based on

traditional segmentation criteria. The third level of

the framework addresses the product positioning for

the defined segments. Here, a product-attribute based

approach is chosen in order to match the customer

needs with suitable products attributes (Lilien et al,

2017).

Figure 2: Framework of the Methodology.

4.2 Description of the Framework

Levels

In this section the three layers of the framework are

described in detail starting with the customer need

level.

As described in chapter II, relevant types of

customer needs are basic needs, emotional needs and

functional needs. When it comes to the development

of a new, potentially disruptive product these needs

are gathered in context of a specific consumption

problem, e.g. using an electric scooter for urban

transport. As shown in (Schuh et al, 2018) and (Sood

and Tellis, 2011), disruptive innovations either offer

completely new performance dimensions for non-

addressed needs or radically simplified solutions for

too complicated products. Hence, needs have to

evaluated in regards to a) the customers’ level of

satisfaction by existing solutions and b) the general

relevance of the need for the customer. A widespread

tool for need the evaluation is the Likert Scale which

allows the transformation of qualitative information

into quantitative data (Meffert et al, 2019). In Figure

3 the customer needs are positioned in a two-

dimensional diagram – hereinafter referred to as

‘Customer Need Portfolio’ – against the

aforementioned criteria ‘relevance’ and ‘level of

satisfaction’. In order to group customers with similar

needs using statistical operations such as clustering

methods, a specific customer is described based on its

needs using a mathematical vector model. For this, i

indicates the number of the customer and m the

number of customer needs as shown in equation (1).

Figure 3: Customer need level described by customer need

profiles and the customer need portfolio.

For a successful product strategy, the right group

of customers (customer segments) have to be

addressed with a suitable offering (product

positioning) (Rogers, 2003; Meffert et al, 2019).

Customer segments are created based on different

geographic, demographic or behavioral segmentation

criteria, e.g. city size, age or customer loyalty, as

shown in Figure 4. Hereby, the customer groups

become ‘targetable’ by various marketing

instruments.

Figure 4: Customer segment level described by

segmentation criteria.

The third level of the framework deals with the

positioning of the product compared to competitor

products. For the visualization of product positioning

strategies, different mapping methods such as

perceptual or preference maps apply (Meffert et al,

2019; Bruhn, 2016). Since this paper aims for

positioning products based on specific product

attributes in relation to addressed and non-addressed

customer needs, an attribute-based perceptual map is

suitable (Lilien, 2017). This map – in the following

referred to as ‘Product Attribute Curve’ (see Figure

5) – lists selected product attributes on the abscissa

which are evaluated regarding their ‘performance

level’ on the ordinate.

Customer Need-based Product Positioning for Disruptive Innovations

303

Figure 5: Product positioning level described by a product

attribute curve.

4.3 Process of the Need-based Product

Positionig

This section explains the overall process of how to

derive a potentially disruptive product positioning on

an attribute-level based on customer needs.

First, addressing the initial critique that standard

market segmentation techniques develop clusters that

are very heterogeneous on a customer need level

(making it difficult to create a successful product-

market-fit), a 3-step approach to create customer

clusters based on their needs is presented. The first

step describes the identification of customer need

similarities. Then, using a clustering algorithm,

customers with similar needs are grouped with every

iteration until only one cluster is left (step 2).

Defining the most suitable number of clusters is the

third step. (Backhaus et al, 2016).

Figure 6: Steps for the creation of customer need clusters.

In statistics, identifying similarities between

objects (here: customers) is done using proximity

measures that calculate the distance between their

defining variables (here: customer needs) (Backhaus

et al, 2016). Since the authors described customers

using vector models in section B, the distance can be

calculated based on the Likert Scale data for every

customer need. For practical applications, a

widespread proximity measure is the ‘Manhattan’-

Metric (Backhaus et al, 2016). For an exemplary set

of three customer profiles, the Manhattan-Metric is

applied (see Figure 6). The results in the so-called

‘distance-matrix’ show that the shortest distance

exists between customer 1 (c1) and customer 2 (c2),

meaning that the similarity between their need

profiles is very high.

Clustering algorithms evaluate the distances

between objects under a wide set of rules in order to

create clusters. Since this process is very complex and

task specific, the selection of a suitable clustering

algorithm (step 2) as well as well as the evaluation of

the appropriate number of clusters (step 3) is out of

the scope of this paper. Interested readers are referred

to (Kuhn and Johnson, 2016; Kassambara, 2017;

Everitt, 2011).

Figure 6: Step 1 of the customer need cluster creation.

The developed customer need clusters from level

1 group similar customer need profiles and, thus,

allow the development of products with a good

product-market-fit. However, addressing these

customer clusters is not yet possible, as this step

requires the identification of mutual characteristics

within the clusters that make them targetable. For

this, segmentation criteria such as geographic,

demographic, behavioral or a combination of them

apply (Kotler and Keller, 2012) In order to identify

identical segmentation criteria between customers

within one customer cluster, a cross-tabulation

approach is used (Backhaus et al, 2016). As outcome,

each previously non-targetable customer need cluster

becomes a differentiable market segment with

homogeneous needs that can be specifically targeted

(see Figure 7).

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

304

Figure 7: Applying cross-tabulation with established

segmentation criteria on need-clusters in order to create

targetable market segments.

Each market segment from the second level

contains customers with similar need profiles. As

explained in section B of this chapter, the

corresponding customer need portfolio visualizes the

assessment of different customer needs against the

criteria ‘level of satisfaction’ as well as ‘relevance’.

As explained here (Christensen, 2015; Schuh et al,

2018; Druehl and Schmidt, 2009), disruptive

innovations either target non-addressed customer

needs (new-market disruptions) or those needs that

are over-fulfilled by current product solutions (low-

market disruptions), hereby creating a strong

differentiation from competitor products that is part

of their success. Hence, there is a close connection

between the customer need profile and the

corresponding product attribute positioning. Using a

new approach that builds on former works of

ULRICH (Ulwick and Osterwalder, 2016), five

different areas within the customer need portfolio are

defined and meant to support the decision-making

process considering if and how the respective needs

should be addressed, namely: Irrelevance, Over-

Fulfillment, Under-Fulfillment, Non -Fulfillment,

Fulfillment. While removing product attributes that

address irrelevant needs sounds like a trivial advice,

many products are over -specified due to ever -

growing specification sheets that are not challenged

with customers (Schuh et al, 2018). Simplifying

product attributes for needs that are over -fulfilled by

current product solutions is the second measure in

order to position products. Differentiation from

competitor products is possible for under-fulfilled

needs by optimizing respective product attributes.

Strong potential to build USP potential lies within

addressing currently non- fulfilled, highly relevant

needs with new product solutions which is mostly

enabled through technological breakthroughs

(Danneels, 2004). This applies for the initially

discussed ‘new-market disruptions’. Last, customer

needs located in the fifth area – fulfilled needs – have

the last potential for differentiation, as they are either

completely fulfilled or of low relevance for the

customer. Hence, aligning product attribute

performance to the established level of competitor

products is the best choice. The area definition in the

customer needs portfolio as well as the derived

measures for the product attribute curve are

visualized in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Deriving product attribute positioning measures

for selective customer needs based on their level of

satisfaction and relevance.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

RESEARCH

Incumbent companies are faced with challenges from

new entrants, increasing commoditization and a more

and more dynamic market in general. Thus, the ability

to constantly innovate and develop new markets

becomes a necessity. Yet, studies show that new

product development success is still a challenge many

companies struggle with. One of the reasons for this

is that often market segments are targeted that are

homogeneous considering traditional segmentation

criteria, but not in regards to the actual needs of the

customers within these segments (Ulwick and

Osterwalder, 2016).

In a previous paper on disruptive innovations

(Schuh et al , 2018) the authors motivate the

importance of a deep understanding of customer

needs and the necessity of deriving corresponding

product attributes that allow a strong differentiation

from competitor products. Such a process requires an

integrative model that combines customer needs,

respective market segments and product positioning.

Customer Need-based Product Positioning for Disruptive Innovations

305

This paper addressed this question by developing

a decision model that integrates all of the above-

mentioned layers. For each layer, description models

for the definition of (a) customer needs, (b) market

segments and (c) product positioning are developed.

Then, explanatory models for (i) a needs-based

customer clustering using similarity algorithms, (ii)

the transformation of customer need clusters into

market segments based on cross-tabulation, and (iii)

need-based derivation of product attribute positioning

is presented.

In the scientific community, the results will foster

the further discussion on how to bridge the gap

between individual customer needs and innovations

with a great product-market fit. Practioners,

especially from marketing and product management,

can use the results as framework in which they can

implement existing tools and herby increase product

success.

Yet, there is still more research necessary. For

instance, until now, the need area characterization

within the customer need portfolio was derived based

on a small number of conducted projects and needs a

more reliable quantitative grounding. Considering the

development of customer need clusters, more

research has to be conducted in regards to the

selection of appropriate clustering algorithms. Last,

the overall success of the models’ implementation in

order to develop potentially disruptive products has to

be validated.

Considering the increasing interest in disruptive

innovation research, we do feel confident that the

important discipline of positioning disruptive

products in relation to customer needs will receive

more attention as well. For this, we encourage other

researches to build upon the developed model in this

paper.

REFERENCES

Christensen, C. M., 2015. What Is Disruptive Innovation?,”

Harvard Business Review, pp. 44–53.

Kim, S., Mauborgne, R., 2016. Der Blaue Ozean als

Strategie.München. Hanser.

King, A. A., Tucci, C. L., 2002. Incumbent Entry into New

Market Niches. The Role of Experience and Managerial

Choice in the Creation of Dynamic Capabilities,”

Management Science, vol. 48,pp.171–186.

Tellis, G. J., 2006. Disruptive Technology or Visionary

Leadership?,” J Prod Innov Manag, vol. 23, pp. 34–38.

Yu, D., Hang, C. C., 2010. A Reflective Review of

Disruptive Innovation Theory,” International Journal of

Management Reviews, vol. 12, pp. 435–452.

Sood, A., Tellis, G. J., 2011. Demystifying Disruption. A

New Model for Understanding and Predicting

Disruptive Technologies,” Marketing Science, vol. 30,

pp. 339–354.

Christensen, C. M., Eichen, S. F. v. d., Matzler, K., 2015.

The innovator's dilemma. Warum etablierte

Unternehmen den Wettbewerb um bahnbrechende

Innovationen verlieren. München. Vahlen.

Hang, C. C., Garnsey, E., Ruan, Y., 2015. Opportunities for

disruption,” Technovation, 39-40, pp. 83–93.

Yu, D., Hang, C. C., 2011. Creating technology candidates

for disruptive innovation. Generally applicable R&D

strategies,” Technovation, vol. 31, pp. 401–410.

Schmidt, G. M., Druehl, C. T., 2008. When Is a Disruptive

Innovation Disruptive?,” J Product Innovation Man,

vol. 25, pp. 347–369.

Castellion, G., Markham, S. K., 2013. Perspective: New

Product Failure Rates: Influence of Argumentum ad

Populum and Self-Interest,” Journal of Product

Innovation Management, vol. 30,pp.976–979.

Reinhardt, R., Gurtner, S., 2011. Enabling disruptive

innovations through the use of customer analysis

methods,” Rev Manag Sci, vol. 5, pp. 291–307.

Chiesa, V., Frattini, F., 2011. Commercializing

Technological Innovation: Learning from Failures in

High-Tech Markets,” Journal of Product Innovation

Management, vol. 28, pp. 437–454.

Talke, K..,

Snelders, D.., 2013. Journal of Product

Innovation Management, vol. 30, pp. 732–749.

Christensen, C. M., Anthony, S. D., Berstell, G.,

Nitterhouse, D., 2007. Finding the right job for your

product,”, vol. 48, 38-+.

Ulwick, A. W., Osterwalder, A., 2016. Jobs to be done.

Theory to practice. New York. McGraw-Hill.

Pohlmeyer, A. E., Identifying Attribute Importance in Early

Product Development. Exemplified by Interactive

Technologies and Age.

Technische Universität Berlin.

Kotler, P., Keller, K. L., 2012. Marketing management.

Boston, Mass. Prentice Hall/Pearson.

Froböse, M., Thurm, M., 2016. Marketing. Wiesbaden.

Springer Fachmedien.

Kotler, P., Armstrong, G., Wong, V., Saunders, J.,2011

Grundlagen des Marketing. München. Pearson

Studium.

Aumayr, K., 2016. Erfolgreiches Produktmanagement.

Wiesbaden. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Meffert, H., Burmann, C., Kirchgeorg, M., Eisenbeiß, M.,

2019. Marketing. Wiesbaden. Springer Fachmedien

Wiesbaden.

Herrmann, A., Huber, F., 2013. Produktmanagement.

Wiesbaden. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Bruhn, M. 2016: Marketing. Grundlagen für Studium und

Praxis.Wiesbaden. Springer Gabler.

Schuh, G., Wetterney, T., Vogt, F., 2018. Characteristics of

Disruptive Innovations. A Description Model Focused

on Technical products, in ISPIM Connects Fukuoka.

ISPIM, Ed.

Schuh, G., Wetterney, T., Lau, F., Schmidt, T., 2018.

Disruption-Oriented Product Planning. Towards a

Framework for a Planning Process for Disruptive

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

306

Products, in Managing Technological

Entrepreneurship: The Engine for Economic Growth.

PICMET '18, Ed.

Tsai, C.-F., Hu, Y.-H., Lu, Y.-H., 2015. Customer

segmentation issues and strategies for an automobile

dealership with two clustering techniques, Expert

Systems, vol. 32, pp. 65–76.

Machauer, A., Morgner, S., 2001. Segmentation of bank

customers by expected benefits and attitudes, Intl Jnl of

Bank Marketing, vol. 19, pp. 6–18.

Du, X., Jiao, J., Tseng,, M. M., 2003. Identifying customer

need patterns for customization and personalization,

Integrated Mfg Systems, vol. 14, pp. 387–396.

Gursoy, D., Chen, M.-H., Kim, H. J., 2005. The US airlines

relative positioning based on attributes of service

quality,” Tourism Management, vol. 26, pp. 57–67.

Cooper, R. G., 2014. Research-Technology Management,

vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 20–31.

Arora, R., 2006. Product positioning based on search,

experience and credence attributes using conjoint

analysis,” Jnl of Product & Brand Mgt, vol. 15, pp.

285–292.

Ibrahim, E. E., Gill, J., 2005. A positioning strategy for a

tourist destination, based on analysis of customers'

perceptions and satisfactions,” Marketing Intelligence

& Plan, vol. 23, pp. 172–188.

Fung, R. Y. K., Popplewell, K., Xie, J., 1998. An intelligent

hybrid system for customer requirements analysis and

product attribute targets determination,” International

Journal of Production Research, vol. 36, pp. 13–34.

Tseng, M. M., Du, X., 1998. Design by Customers for Mass

Customization Products,” CIRP Annals, vol. 47, pp.

103–106.

McAdams, D. A., Stone, R. B., Wood, K. L., 1999.

Gestaltung der Integration von Lieferanten in den

Functional Interdependence and Product Similarity

Based on Customer Needs, Research in Engineering

Design, vol. 11, pp. 1–19.

Yang, C.-C., Yang, K.-J., 2011. An integrated model of

value creation based on the refined Kano's model and

the blue ocean strategy, Total Quality Management &

Business Excellence, vol. 22, pp. 925– 940.

Borgianni, Y., Cascini, G., Rotini, F., 2012. Rotini,

“Investigating the Patterns of Value-Oriented

Innovations in Blue Ocean Strategy,”International

Journal of Innovation Science, vol. 4, pp. 123–142.

Slater, S. F., Mohr, J. J., 2006. Successful Development and

Commercialization of Technological Innovation.

Insights Based on Strategy Type, J Prod Innov Manag,

vol. 23, pp. 26–33.

Kassicieh, S., Walsh, S., Cummings, J. C., McWhorter, P.

J., Romig, A. D., David Williams, W., 2002. Factors

Differentiating the Commercialization of Disruptive

and Sustaining Technologies”, vol. 49, pp. 375–387.

Rueda, G., Kocaoglu, Dundar, F, 2008. Diffusion of

emerging technologies. An innovative thinking

approach, in Technology Management for a Sustainable

Economy. IEEE, Ed., 2008, pp. 672– 697.

Sandberg, B.., 2008. Managing and marketing radical

innovations. Marketing new technology. Abingdon

England, New York, N.Y. Routledge.

Rogers, E. M., 2003, Diffusion of innovations. New York.

Free Press.

Lilien, G. L., Rangaswamy, A., de Bruyn,, A., 2017.

Principles of marketing engineering and analytics.

Backhaus, K., Erichson, B., Weiber, R., Plinke, W., 2016.

Clusteranalyse,” in Multivariate Analysemethoden. K.

Backhaus, B. Erichson, W. Plinke, R. Weiber, Eds.

Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016,

pp. 453–516

.

Kuhn, M., Johnson, K., 2016. Johnson, Applied predictive

modeling. New York. Springer.

Kassambara, A., 2017. Practical guide to cluster analysis in

R. Unsupervised machine learning. Frankreich.

STHDA.

Everitt B., 2011. Cluster analysis. Chichester. Wiley.

Backhaus, K., Erichson, B., Weiber, R., Plinke, W., 2016.

Kreuztabellierung und Kontingenzanalyse, in

Multivariate Analysemethoden. K. Backhaus, B.

Erichson, W. Plinke, R. Weiber, Eds.

Druehl, C. T., Schmidt, G. M., A Strategy for Opening a

New Market and Encroaching on the Lower End of the

Existing Market.

Production and Operations Management, vol. 17, pp. 44–

60, 2009

Danneels, E., 2004. Disruptive Technology Reconsidered:.

A Critique and Research Agenda,” J Product

Innovation Man, vol. 21, pp. 246– 258.

Customer Need-based Product Positioning for Disruptive Innovations

307