Telehealth: A Viable Option for Optimizing Health System

Performance during COVID-19: Call to Action for Future Pandemics

Layal Mohtar

a

and Nabil Georges Badr

b

Higher Institute of Public Health, Saint Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon

Keywords: Health Care, Quadruple Aim, Covid Pandemic, Scoping Review, Healthcare Services, Health System

Performance.

Abstract: Delve into the 21st century to welcome telehealth! It has taken so long coming, only to be accelerated by the

COVID -19 pandemic. With the advent of telehealth solutions, healthcare systems are on the edge of the

biggest gush in activity in over a century. In this paper, we look for evidence in the literature that treats the

disruption introduced by Telehealth diffusion and the resulting, long awaited, contribution to optimizing

health system performance. In our paper, we attempt to use the scoping review to detect evidence to answer

this question. We performed a search up to April of 2021. Data were extracted on general study characteristics,

clinical domain, technology, setting, category of outcome, and results. We then concluded with a synthesis of

the information and call to action. We then coded the findings through the lens of the quadruple aim, provided

reflections from the scoping review to inform how telehealth can be a dynamic element of system resilience.

Though faced with unintended consequences, telehealth promises to be a viable alternative to in-person care,

optimizing health system performance especially in times of constrained resources during a pandemic.

1 INTRODUCTION

As the pressing need to expand the delivery of

healthcare has surpassed the traditional limits of

implementation, the substantial burden of the

COVID-19 pandemic has placed the provision of

healthcare services under duress. Embracing

telehealth paves the way for all those vigilant in the

work of improving and transforming health care

systems, to usher in the new era of delivering

healthcare services through a reconfiguration of

technology to improve healthcare.

A US study conducted before the COVID-19

Pandemic, shows that the use of telemedicine was in

the most part, to address issues of accessibility and

reach of care to underserved areas (Barnett, 2018).

By January 2020, as COVID-19 was becoming

ostensible, the demand for telehealth services spiked

a 2000% increase in visits before the end of April

2020, and in-person visits declined 80% (Kaplan,

2020). In response to the pandemic, some research

has reported the surge in the use of telehealth services

as an option for clinic appointments, in some cases,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2771-3169

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7110-3718

83% of the surveyed, cited the COVID-19 pandemic

as the impetus for implementation of such services

(Parisien et al, 2020).

Quick telehealth expansion is an astounding

example of what can happen in a matter of weeks that

was reputed to take a decade. As we explore the

outcomes associated with the implementation of

telehealth technology in healthcare ecosystems, we

are mindful of the challenge in bridging the gap

between the potential for extending healthcare

technology to overcome the disruption in the

provision of health services and the potential impact

on the quality of healthcare services and health

ecosystem performance.

This phenomenon was a worldwide event as

countries moved towards a hurried adoption of

telehealth-based practice to reduce the risk of the

pandemic spread. Health systems have added billing

codes on their schedules that differentiate

Telemedicine based care. Even prehospital telecare

became common, more in Europe than the US

(Winburn et al, 2018). The uptake of telehealth

implementations has been reported in Urgent and Non

Mohtar, L. and Badr, N.

Telehealth: A Viable Option for Optimizing Health System Performance during COVID-19: Call to Action for Future Pandemics.

DOI: 10.5220/0010647400003123

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2022) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 279-288

ISBN: 978-989-758-552-4; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

279

Urgent Care (Parisien et al, 2020), clinical

consultations (Smith et al, 2020), for children and

adult care (Tan, 2020) and has accelerated with the

increased restrictions. Even developing countries

reported an increase in video consultations as a

primary means of care (Helou et al, 2020). This is an

indication that Telehealth use came as an urgent,

temporary, alternative care to face – face

consultations, fuelling the reconfiguration of the care

ecosystem (Badr et al, 2021). Technology

implementers have joined the front line of the medical

provider workforce to deploy and maintain the

platforms that make these “at a distance” services

possible. A new level of interaction between the care

team and a new set of sociotechnical complexity

arise.

Have some implementations of telehealth

solutions disrupted the quality of care or were they a

long awaited contribution to optimizing health system

performance? In our paper, we attempt to use the

scoping review to detect evidence to answer this

question.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Telehealth: Care at a Distance

Efficiency of healthcare service, effectiveness in

resource usage, and patients’ satisfaction occupy

central attention in the discourse around care at

distance. These sustainability principles are essential

to the optimization of the services that would

otherwise be traditionally with one building and

controlled setting. With telehealth technologies, it has

become possible to extend these principles to distance

care solution such as care at home for instance (Polese

et al., 2018). Hence, telehealth is the delivery of

healthcare services by healthcare professionals using

information and communication technologies, for the

exchange of valid information for diagnosis,

treatment, and injuries and prevention of disease,

evaluation and research, and the healthcare providers’

continuing education (Fisk et al., 2020).

The modes of delivery of telehealth incorporate

technologies such as videoconferencing, mobile

applications, and secure messaging. Furthermore,

telehealth services include provider-to-provider

services with patient presence, provider to provider

without patient presence, tele monitoring, and health

education etc. (Tuckson et al., 2017). In our paper, we

1

http://www.ihi.org/Topics/TripleAim/Pages/Overview.

aspx

refer to telehealth as the overarching term to signify

the service of providing care, which the central notion

of our work.

2.2 Optimizing Health System

Performance

The pandemic has accentuated the focus on distant

care, pushing the limits on telehealth deployments for

safety concerns and for the optimization of the

resources in the healthcare systems. The facilitation

of telemedicine services has made care possible and

accessible. Though in some cases disruptive to the

existing traditional processes and care delivery

models, this new way of mainstream care may

continue to contribute to optimizing the provision of

care. Indeed, practitioners and academics have

advocated leveraging health information technology

to achieve the “triple aim” of healthcare reform

(Bisognano and Kenney, 2012; Sheikh, 2015).

Improving care quality while containing costs of

care are the central arguments for the Triple Aim

framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare

Improvement (IHI)

1

for optimizing health system

performance. The framework directs health systems

to pursue three dimensions, simultaneously for

Improving the patient experience of care (including

quality and satisfaction); Improving the health of

populations; and Reducing the per capita cost of

health care. Extending this recommendation, the

Quadruple Aim adds the dimension of improving the

work life of health care providers, including

clinicians and staff (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014).

In our scoping review, we choose the Quadruple

Aim Framework as a lens to evaluate our findings and

synthesize on lessons we can glean from the current

literature.

3 METHODOLOGY

We conducted a scoping review to evaluate the

potential for improvement in the healthcare

ecosystem performance driven by the implementation

of telehealth. A scoping review, in this case, can be

useful to synthesize the relevant evidence in the

literature and identify opportunities for further

research or calls to action (Munn et al, 2018). Our

search involved online databases including Google

Scholar and PubMed, exploring articles from the

Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, Journal of

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

280

American College of Surgeons, International Journal

of Medical Informatics, New England Journal of

Medicine, JAMA Dermatology, NEJM Catalyst

Innovations in Care Delivery, JMIR Public Health

Surveillance, International Journal of Environmental

Research and Public Health, and JAMA Intern Med.

The initial search was performed using the search

filter of "Telehealth" AND "Impact on Quality of

Care” in which 209 queries were retrieved.

Then, in a second step, we refocused our lens on

the combined terms "Telehealth" AND "Quadruple

Aim" AND "impact on quality of care" to isolate the

content that would address our research question. We

found limited material (6 papers) on the narrow

subject. In scanning the literature, the terms telehealth

and telemedicine were found to be often used

interchangeably which echoed a primary concern

making the evidence more problematic to evaluate.

Upon review, we found that most telehealth literature

refers to telehealth as the broader practice of the

concept of delivering healthcare services at a distance

and refers to examples from the field of practice for

telemedicine as the term that describes the actual

practice of medicine at a distance. Therefore, we

expanded our narrow search on the combined terms

"Telemedicine" AND "Quadruple Aim" AND

"impact on quality of care" (six papers were also

found).

Thus, our results offered little evidence in the

literature to support the conversation on the potential

of telemedicine for healthcare improvement guided

by principles of the quadruple aim. We found sparse

evidence on how Telehealth and Telemedicine use

would influence the ability of a healthcare ecosystem

to fulfil the quadruple aim. We therefore proceeded

with the initial 209 articles in an attempt to be most

encompassing to yield the subset of articles for our

coding, hoping to develop hidden information in the

direction of our research question. After the

screening, the relevant articles were identified, only

those that were written in the English language were

chosen. Duplicate publications in different journals

were removed and student dissertation excluded.

Articles were read in full to confirm eligibility. The

review was narrowed to 50 articles. After carefully

inspecting the identified articles, we further refined

our synthesis to extract evidence of improvement in

the healthcare system performance. Each author

reviewed findings individually, and then coded using

themes from the four principles of the quadruple aim:

(1) Improving the patient experience of care,

(2) Improving the work life of healthcare

providers,

(3) Reducing the per capita cost of health care;

And

(4) Improving the health of populations.

The coding revealed secondary codes that we

categorized under the main codes, adding depth to our

findings.

4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Despite the existence of some literature on Telehealth

and Telemedicine to impact on quality of care, few

papers trace the connection between these same

technologies and the context of Quadruple AIM.

The dialogue in the context of telemedicine and

the impact on quality in the context of the goals of the

quadruple aim has been limited to very few

inferences. One paper addressed how telemedicine

and smartphones are enabling more flexible and

mobile work (Nakagawa and Yellowlees, 2019) with

emphasis on continuity of care at home (Helmer-

Smith, et al, 2020). In other examples, healthcare

technology in general has shown evidence of impact

on healthcare quality (Buntin, 2011; Fiani, 2020).

Innovative health technologies such as telehealth can

possibly help improve training, patient centeredness,

access, agreeableness, decency, efficiency, quality,

outcomes, and cost viability (Fund, 2017; Lopo,

2020). Therefore, we found sparse evidence on how

Telehealth and Telemedicine use would influence the

ability of a healthcare ecosystem to fulfill the

quadruple aim; this paper puts the focus on this

context, as our scoping review isolated the concepts

of the quadruple Aim in the context of Telehealth

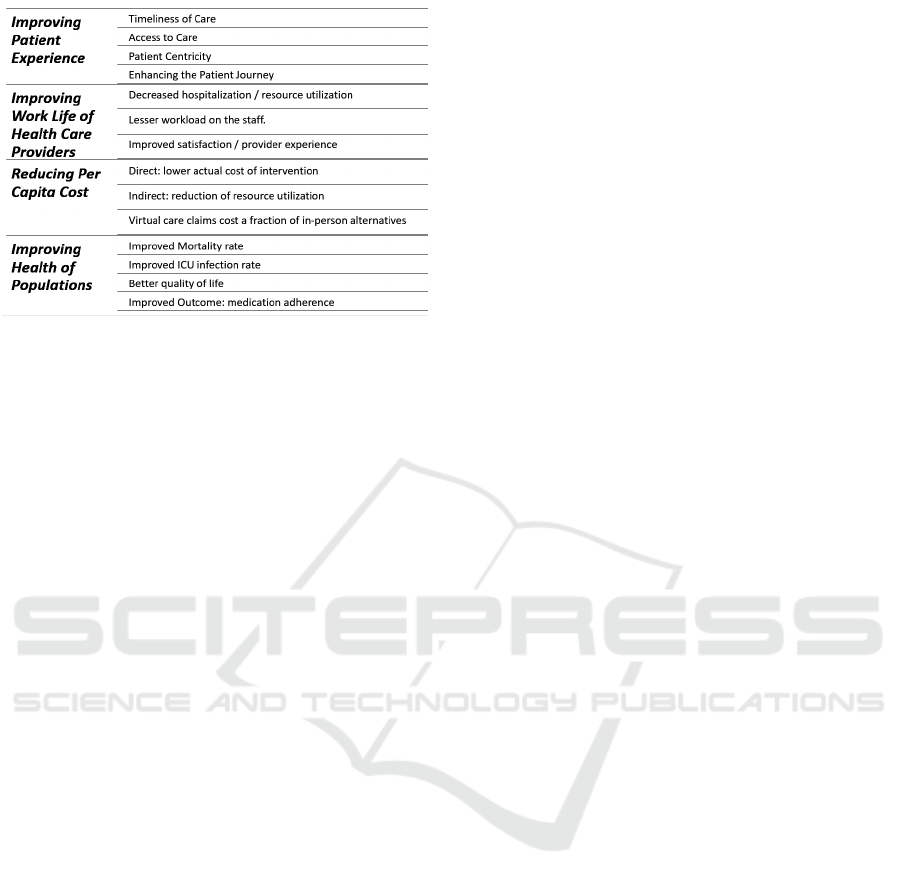

adoption (Figure 1).

We have identified some works that demonstrate

telehealth as a technology to improve the patient

experience through timeliness of care (Caffery et al,

2016; Gattu et al, 2016; Lum et al, 2020); and better

access (Qureshi et al, 2015; Lurie and Carr, 2018;

Lavin et al, 2020); leading to an improved quality of

life for care seekers (Waibel et al, 2017). Other works

connected a decreased hospitalization and resource

utilization to the implementation of telehealth

solutions (Gattu et al, 2016), lessening the workload

on the care staff (Bashir and Bastola, 2018), thus

improving the work life of health care providers

(Lopo et al, 2020). Our investigation revealed that

Telehealth has the potential of reducing cost of care

(Mehrotra et al, 2013; Liu et al, 2016) and improving

the outcome of care (Flodgren et al, 2015; Snoswell

et al, 2017).

Telehealth: A Viable Option for Optimizing Health System Performance during COVID-19: Call to Action for Future Pandemics

281

Figure 1: Telehealth & Optimizing Health System

Performance – from our Scoping Review.

4.1 Improving Patient Experience of

Care

Timeliness of Care: Evidence suggests that the

adoption of telehealth has improved timely access to

care, especially for low acuity conditions or serious,

time-sensitive situations; hospitals are adopting

telehealth to improve operational efficiencies and

provide timelier access to specialty care (Lum et al,

2020).

Our review has identified a case, with a

significant (75%) reduction in patient wait times for

urgent care conditions, through a telehealth triage

program (Caffery et al, 2016). In another case, while

chronic pain clinic patients waited for an in person

consultation, they have received useful advice in 86%

of cases, through their telehealth portals, reducing the

negative impact of the long wait times on their day to

day lives. Using virtual visits for low-acuity patients,

reduced the emergency departments wait from 2.5

hours to 40 minutes (Caffery et al, 2016) and timely

diagnosis of minor illnesses in children and

adolescents has improved school attendance (Gattu et

al, 2016).

Access to Care: Our scoping review has

identified instances of improved access to care with

telehealth services, while also recognizing access

barriers of technology reach in some rural populations

of Central Asia (Qureshi et al, 2015) and Africa

(Lurie and Carr, 2018). By placing the technologies

directly in patients' homes or at local clinics near them

(Lavin et al, 2020), patients have reported an

improved quality of life, ameliorating their

experience and almost half strongly disagreed

whether they still must see the provider in person and

most (86%) of them strongly agreed on the use of

telehealth again (Waibel et al, 2017).

Patient Centricity: Consumers are willing to use

telehealth for everything from prescription renewals

to chronic disease management and behavioural

health (Lum et al, 2020). Patients seeking virtual care

rated their satisfaction as “very good” to “excellent”

(Thomas et al, 2020). To note, patients feel in charge

if their records and the levels of care they receive as

their contribution and input through online available

systems, with complete histories, and physical

examinations, contribute to the outcome of correct

diagnoses in 76.5% of the visits (Schoenfeld et al,

2016). Still, one study identified that lab tests may

have been unnecessarily ordered due to a

conservative approach of ordering antibiotics

(Mehrotra et al, 2013).

Enhancing the Patient Journey: Telehealth

implementations have brought the information to the

patients, whereby a decrease in emergency

department’s visits (Wosik et al, 2020), especially in

pediatric visits (DeJong et al, 2014). Patients are

finding their answers with Telemedicine tools and

more digital means of interaction with the care

providers. Case studies have reported a two-fold

improvement in the completeness of documentation

and increase in appropriate antibiotic prescribing

within six months due to the use of telehealth services

(DeJong et al, 2014). This implies a lesser workload

on the care staff and reduction of fatigue. Other cases

have noted a reduction in hospitalizations, length of

stay, and 30-day readmission rate (DeJong et al,

2014), especially among the home based telehealth

patient population (Lum et al, 2020). Video visits

combined with remote patient monitoring enable

healthcare organizations to better monitor patients,

relieve workload and reduce consumption of care

resources.

4.2 Improving Work Life of Health

Care Providers

Decreased Hospitalization / Resource Utilization:

Hospitals are adopting telehealth to improve

operational efficiencies and provide timelier access to

specialty care (Lum et al, 2020). For example, timely

diagnosis, with the use of telehealth for minor

illnesses in children and adolescents decreased

emergency department utilization by 22% (Gattu et

al, 2016). This reduction reflects on lesser workload

on the staff.

Improved Satisfaction / Provider Experience:

Telehealth has improved the quality of the nursing

practice and reflected on the quality of the care

services (Bashir and Bastola, 2018). With the

implementation of telehealth in the model of care,

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

282

satisfaction levels at the provider experience have

improved (Caffery et al, 2016). Studies in our scoping

review reflected on healthcare practitioner’s morale

affecting workforce engagement and safety such as

workforce burn-out (Sikka et al, 2015). The literature

review has noted provider experience satisfaction in

94% of cases of telehealth implementations (Lopo et

al, 2020).

4.3 Reducing per Capita Cost of Health

Care

Our investigation revealed that Telehealth has the

potential of reducing cost of care. Telehealth

programs can be cost saving for intermediate and

high-risk patients over a 1- to 5-year window (Liu et

al, 2016). The cost reduction can be direct through

actual cost of intervention or consultation and also

indirect through reduction in the consumption of

hospital services (Mehrotra et al, 2013). Service cost

a weighted average of $47.35/case, compared with

$133.60/case for traditional refer (Caffery et al,

2016). In one case, the service cost has decreased to

third for traditional referrals (Caffery et al, 2016) and

virtual care claims have saved the health plan an

average of 30% per claim (Lum et al, 2020).

4.4 Improving Health of Populations

Telehealth consultations contribute to the adherence

to clinical management guideline (Steinman et al,

2015), and the satisfaction of both patients and

providers (Waibel et al, 2019) and showed no

significant difference in adherence to treatment

guidelines across the multiple care modalities

(primary care, urgent care, etc.) of which

telemedicine has become one. There has been some

pleasing news on the decrease in mortality rates in

ICUs (DeJong et al, 2014) and especially concerning

the reduction of risks (30%) of sepsis (Steinman et al,

2015). Telemedicine intervention decreased overall

mortality and length of stay within progressive care

units without substantial cost incurrences (Armaignac

et al, 2018). Additionally, we found evidence of

improved quality of life where participants with

diabetes had a lower glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c

%) levels, a decrease in LDL, and blood pressure

(Flodgren et al, 2015). DeJong et al 2014 elaborated

that uniform transparency about care and referral

protocols would be helpful. Creating a consumer-

dominated regulator, which could compile

information on e-visit websites’ performance, may

improve outcomes. Telehealth tools can aid in

improving medication adherence, thus contributing to

improved patient outcomes, decreased likelihood for

hospital admissions, reduced healthcare cost burden,

and improved mortality in heart failure patients, a

study finds (Broadway, 2021). An interesting article

in our review, noted that by understanding societal

values such as patient preference and willingness-to-

pay, we might be able to quantify the value of new

interventions and extra-clinical outcomes associated

with telehealth more effectively (Snoswell et al,

2017).

5 REFLECTION FROM THE

SCOPING REVIEW

Telehealth implementations are starting to prove

some contributions for optimizing health system

performance, as evidenced by our scoping review.

The literature provides a favourable view on the

potential for Telehealth to improve the patient

experience of care through increasing access to timely

care, focusing more on the needs of care for each

patient. With Telehealth there is a great opportunity

to decrease hospitalization and optimize health

resource utilization. This will also drive an

improvement in the quality of life of the practitioners,

lower the cost of care, improve medication adherence,

etc. leading to improved health of the population. As

a viable alternative to in-person care, Telehealth is

now a dynamic element of care system resilience. The

scoping review has inspired a few calls to action to

reign in and understand the risks incurred while

providing care virtually and how an interruption in

the virtual service may affect the outcome. The

complex care ecosystem with all its actors and

stakeholders must be prepared and the access to latent

information must be ushered to curb likely misuse.

The literature does not reflect on how privacy was

ensured in such visits and what happened when a

breach in privacy and confidentiality took place and

how this affected the satisfaction (Badr et al, 2021,

January). The COVID-19 pandemic coupled with the

rapid explosion of telehealth services grants an

unparalleled opportunity to examine related ethical,

legal, privacy and confidentiality, information

technology infrastructure and social challenges

during a time of crisis in healthcare. Just like the

current and potential benefits, conversely telehealth

has limitations which are essential to address into the

mainstream of telehealth deployment.

Telehealth: A Viable Option for Optimizing Health System Performance during COVID-19: Call to Action for Future Pandemics

283

5.1 Unintended Consequences of

Benefits

Innumerable technologies can be applied through

telehealth to empower patients to have control over

their healthcare, but despite current research, rigorous

investigation needs to be completed to determine all

the possibilities where technology could be beneficial

and useful (fit for use), and also under which

circumstances (fit for purpose). A full understanding

is needed in order to curb the risk of some unintended

consequences.

Fit for Use: Although, one of the benefits of

telehealth implementation is reducing the cost

through providing access to rural areas, reducing

emergency department utilization, and avoiding

hospitalizations; implementing telehealth may not be

cost-effective in the short term due to high

infrastructure and operational cost and capability

building required for the mainstream of practitioners

to use the new technologies. Our review highlighted

the importance of removing financial barriers to use

telemedicine, implementing waivers to purchase

essential devices and internet access, and offering

education and training, could be options in that

direction.

Fit for Purpose: For instance, attention must be

given to avoid risks of unintended consequences.

Examples of such risks are identified in cases of

patient interaction and practitioner satisfaction in

administering care. Studies have persistently shown

that telehealth implementation can improve patient

outcomes due to a timely patient-provider interaction.

Telehealth can encourage more personal encounters

and assist healthcare providers by increasing their

ability to develop improved relationships with

patients, which may lead to better patient compliance

and thus enhance patient outcomes. However, in the

absence of tactile examination, physicians may

perceive the absence of the physical contact with the

patient as inadequate evaluation, incomplete

diagnosis or inappropriate treatment. Thus, a dual

need for evidence-based provision of care along with

easy contextual upskill may be strategically

addressed through a complementary approach

between physical and virtual care. Results of another

study showed that 42.9% of doctors believed that

telemedicine disrupts the doctor-patient relationship

and causes a breach of patient privacy. Cyber related

malpractice insurance would be required for

telehealth practitioners to protect patients from fake

providers and breaches in data security and privacy

(Gogia et al, 2016).

Risks of Technology Fatigue among

Practitioners: Studies in our scoping review

reflected on healthcare practitioner’s morale affecting

workforce engagement and safety such as workforce

burn-out. Telehealth has improved the quality of the

nursing practice which reflected on the quality of the

care services. In addition to reducing the burden of

scheduling, physical and mental exhaustion of the

care providers, telehealth helps lessen transportation

costs for the latter, relieve time lost at work, improves

access to specialists, and promotes continuity in care.

This is a significant improvement to the work life of

health care providers, leading to a better system

performance overall. Opposing views may see that

when people spend a lot of time virtually, may expose

health care professionals to “zoom fatigue” which

may eventually reflect on their ability to provide care

– A moderation is required with the use of virtual

platforms of communication.

5.2 Telehealth a Dynamic Element of

System Resilience

Resilience is commonly portrayed as a positive

capability that allows actors in a system to thrive in

dynamic contexts, adapting, reconfiguring and

developing sustainability (Pisano, 2012). A resilient

healthcare system exhibits an ability to overcome the

disruption in healthcare services the latest

experiences provide evidence that telehealth is no

more the cherry on top but has become an essential

component of care delivery. Telehealth aids the

healthcare system in achieving healthcare equity by

closing care gaps that have been created by current

care models and hence ensuring continuity of care.

After decades of measured implementation of

telemedicine and telehealth (Flores et al, 2020), the

COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed not

only the frequency of patient-clinician visits

conducted via technology across a distance, but also

the urgency to practice at a distance, in order to

prevent the spread (Turer et al, 2020). Telehealth

became a component of the personal protective

equipment gear, designated as Electronic PPE

(ePPE), in the medical practice (Wosik et al, 2020),

giving this new interaction experience a mainstream

(Vilendrer et al, 2020; Li et al, 2020). Thus, bridging

the digital divide for a tranche of the population, and

creating new challenges for others vulnerable sectors

of society (Ramsetty and Adams, 2020). Clinicians

now could practice from the hospital and from home.

While practitioners used teleconferencing equipment

and connected remote devices to collect their patients

vitals and provide a remote assessment (Badr et al,

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

284

2021), patients were able to access their information

through their mobile app, interfaced with the health

record. (Munn et al, 2020). Although extending

healthcare engagement into the patient home was

pursued out of necessity, it is evolving around easier

access to care and timely patient-provider interaction.

While Telehealth can facilitate swift and

successful reconfiguration of care, it also creates

tensions among the complex health system that

require careful consideration (Cho and Robey, 2007).

A call to action is indispensable now, as we embark

on this untethered diffusion of telehealth innovations.

Firstly, when evaluating the literature, we found

lack of evidence in studies that shown the impact of

technology interruption on the care provided. The

literature did not depict whether any adverse events

took place while providing care virtually and how an

interruption in the virtual service affected the

outcome. Providers may potentially become more

frustrated and stressed out of dealing with patients

who delay treatment.

Secondly, when scoping to the future, healthcare

organizations shall assess the organization readiness,

put the policies in places, provide education and

continuous support, check financial reimbursements,

consider IT breakdowns, consider laws of physician

provision of services within the boundaries, and most

importantly, consider privacy and confidentiality. All

these factors shall be sought when determining the

future of telehealth.

Thirdly, access to telemedicine software shall be

escorted with simple guidelines on its proper use and

what to do in case an interruption happens. A

continuous evaluation and monitoring model shall be

put in place to unceasingly assess the system.

Finally, decision-makers still lack adequate

information on comparing the effects of telemedicine

applications to alternative health care strategies. They

also lack good evaluation of the infrastructure

implications and financial requirements for

sustaining telemedicine post COVID. Telemedicine

shall be included as a part of regional disaster health

care systems and provide some of the needed

protections for patients and providers. Disaster

planners and telehealth clinicians shall leverage

technology to improve health care delivery and

prevent the disruption of services during such times

(Gogia et al, 2016).

5.3 Telehealth – Viable Alternative to

In-person Care

The former year has brought the vital nature of virtual

care to the vanguard. Mitigating the spread of the

COVID -19 pandemic has linked isolated patients,

provided care for non-COVID-19 patients, and led to

the accelerated diffusion of telehealth services.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen the

perceptual cycle of ineffective/absent public

healthcare processes compounded by lack of access

to healthcare services. The provision of health care

services through telehealth technologies has revealed

a reassuring effect in the lives of patients.

The public is increasingly in need to access

personalized advice with ease, which will lead to

better quality of healthcare services and, particularly,

improving the overall patient experience. In this era

of Netflix, Uber, Amazon, Zoom, mobile banking,

and a technology facility that enables a 3-year-old to

log in to online classes, unaided, it will not be proper

for the healthcare sector to tumble behind. An average

consumer finishes nearly all aspects of their life

online; healthcare shall be just as convenient,

reachable, and innocuous as online banking.

Leveraging telehealth may produce a higher level

of access and new ways for patients and providers to

participate in the care system resulting in increased

satisfaction for both patients and providers.

Telemedicine while evolving and changing the

current landscape of healthcare, can in a way take us

back to a time when home visits were a part of normal

practice; however, it is now virtually (Shockley,

2020). Immunocompromised, homebound or patients

who live in remote areas, for example, could receive

uninterrupted access to healthcare services.

Furthermore, other patients who want to save time

and cost by reducing travel may continue to seek

virtual care if it is available.

Progressively, for telehealth to become a more

viable alternative to in-person care, research

recommends that healthcare leaders must be less

reactive and more adaptive in the development and

implementation of telehealth solutions (Shockley,

2020) in order to face the challenges in this complex

healthcare ecosystem,. Henceforth, the authors offer

a few recommendation, as calls to action, motivated

by of the findings of this review

Firstly, as we look forward, virtual care will

persist to build the needed foundation to provide safe

and effective care with the right clinician, at the right

time, and at the convenience of the patient. Remote

patient care should be provisioned virtually to

improve effectiveness and enhance patient outcomes.

It offers instantaneous communication with the

healthcare provider at the convenience of the patient

(according to his or her time schedule, saving travel

time for those in rural areas). With the rapid

expansion of telemedicine in the light of the COVID-

Telehealth: A Viable Option for Optimizing Health System Performance during COVID-19: Call to Action for Future Pandemics

285

19 pandemic, ensuring that remote care reaches

diverse, low-income patients and promotes health

equity rather than exacerbating health disparities is

critical. One important aspect to take into deliberation

is that telemedicine may not be accessible to specific

individuals with disabilities and older adults, and

hence affects the treatment delivery via telehealth

technology; the odds of leveraging telemedicine will

be those aged 64 or younger. As mental health

problems are more prevalent in older adults, tele-

mental health services are urgently needed, especially

during the pandemic, for this age category.

Secondly, a deployment of a digital health

strategy that includes telehealth can be effective to

decrease service costs, improve satisfaction, and

improve the entire experience as the hospital rooms

will be extended outside of the physical facility and

into patients’ homes. Such strategy will move us in

the direction of optimizing health system

performance. Nevertheless, in the implementation of

telehealth, we shall acknowledge the perilous role of

the workforce in the healthcare revolution (Fiks et al.,

2021). To ensure that the service that is delivered to

the patient is a service of superior quality, some

aspects of the patient journey are still to be evaluated.

Improvement programs in telehealth technology must

seek the participation of practitioners as important

ambassadors for programmatic success (Smith et al,

2020).

Thirdly, for the near future, Telehealth ought to be

first, an extension, not a replacement of traditional

care services where we shall monitor for those

potentially negative effects and mitigate them. A

quality improvement system is needed to ensure that

services are being provided within best practice

guidelines, demanding quality of the care monitoring

across all levels regardless of location; by monitoring

compliance to standardized treatment protocols, data

collection procedures, and professional behaviour.

5.4 Summary and Calls to Action

Telehealth endures to advance in both developed and

developing countries within the all-embracing setting

of information technology. The former year has

brought the vital nature of virtual care to the

vanguard. Mitigating the spread of the COVID -19

pandemic has linked isolated patients, provided care

for non-COVID-19 patients, and led to the

accelerated diffusion of telehealth services. During

the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen the

perceptual cycle of ineffective/absent public

healthcare processes compounded by lack of access

to healthcare services. The provision of health care

services through telehealth technologies has revealed

a reassuring effect in the lives of patients, especially

during constraints imposed by the pandemic

response.

Our review is valuable in producing calls to action

to improve the performance of the healthcare

ecosystem through Telehealth, in response to

pandemics (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Calls to action to improve the performance of the

healthcare ecosystem through Telehealth during

pandemics.

Hence, designers and implementers of the

telehealth solutions must ensure broader accessibility

to include unencumbered access for people with

disabilities, special needs, and provide governance

and oversight through a comprehensive deployment

strategy with a quality improvement system to reduce

the potential risks of service disruption.

Moreover, technology developers must forge

partnership in the implementation of telehealth that

include users of the technology experience (care

seekers and givers) for value co-creation to

complement the existing complex care ecosystem.

Finally, we call on disaster planners to include

telehealth services disaster risk reduction plans and

work on raising the awareness of use, train on better

usage to improve preparedness and enhance the

resilience of the health provision ecosystem.

6 CONCLUSION

The scoping review provides a few lessons from the

literature. Telehealth has crossed the stage of

disillusionment in the technology hype cycle (Fenn

and Raskino, 2008). The technology’s potential for

mainstream application has become more broadly

understood. Telehealth, a mode of providing care at a

distance has entered the mainstream largely gated by

the latest pandemic needs. We have learned how

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

286

Telehealth become a significant mediator for the

resilience of the care system during the COVID-19

Pandemic.

REFERENCES

Alami, H., Lehoux, P., Gagnon, M. P., Fortin, J. P., Fleet,

R., & Ahmed, M. A. A. (2020). Rethinking the

electronic health record through the quadruple aim:

time to align its value with the health system. BMC

medical informatics and decision making, 20(1), 1-5.

Armaignac, D. L., Saxena, A., Rubens, M., Valle, C. A.,

Williams, L. S., Veledar, E., & Gidel, L. T. (2018).

Impact of Telemedicine on Mortality, Length of Stay,

and Cost Among Patients in Progressive Care Units:

Experience From a Large Healthcare System. Critical

care medicine, 46(5), 728–735.

Badr, N. G., Carrubbo, L., & Ruberto, M. (2021).

Responding to COVID-19: Potential Hospital-at-Home

Solutions to Re-configure the Healthcare Service

Ecosystem.

Badr, N., Drăgoicea, M., Walletzký, L., Carrubbo, L., &

Toli, A. M. (2021, January). Modelling for Ethical

Concerns for Traceability in Time of Pandemic “Do no

Harm” or “Better Safe than Sorry!” In Proceedings of

the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences (p. 1779).

Barnett, M. L., Lau, A. S., & Miranda, J. (2018). Lay health

worker involvement in evidence-based treatment

delivery: a conceptual model to address disparities in

care. Annual review of clinical psychology, 14, 185-

208.

Bashir, A., & Bastola, D. R. (2018). Perspectives of nurses

toward telehealth efficacy and quality of health care:

pilot study. JMIR medical informatics, 6(2), e35.

Bisognano, M., & Kenney, C. (2012). Pursuing the triple

aim: seven innovators show the way to better care,

better health, and lower costs. John Wiley & Sons.

Bodenheimer, T., & Sinsky, C. (2014). From triple to

quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the

provider. The Annals of Family Medicine, 12(6), 573-

576.

Broadway, D. M. (2021). Implementation of Telephone-

based Medication Adherence Conferences to Improve

Health Outcomes of Heart Failure Patients.

Buntin, M. B., Burke, M. F., Hoaglin, M. C., & Blumenthal,

D. (2011). The benefits of health information

technology: a review of the recent literature shows

predominantly positive results. Health affairs, 30(3),

464-471.

Caffery, L. J., Farjian, M., & Smith, A. C. (2016).

Telehealth interventions for reducing waiting lists and

waiting times for specialist outpatient services: A

scoping review. Journal of telemedicine and telecare,

22(8), 504-512.

Cho, S., Mathiassen, L., & Robey, D. (2007). Dialectics of

resilience: a multi–level analysis of a telehealth

innovation. J. Inf. Technol, 22(1), 24-35.

Chuo, J., Macy, M. L., & Lorch, S. A. (2020). Strategies for

Evaluating Telehealth. Pediatrics, 146(5).

DeJong, C., Santa, J., & Dudley, R. A. (2014). Websites

that offer care over the Internet: is there an access

quality tradeoff?. JAMA, 311(13), 1287-1288.

Fenn, J., & Raskino, M. (2008). Mastering the hype cycle:

how to choose the right innovation at the right time.

Harvard Business Press.

Fiani, B., Quadri, S. A., Farooqui, M., Cathel, A., Berman,

B., Noel, J., & Siddiqi, J. (2020). Impact of robot-

assisted spine surgery on health care quality and

neurosurgical economics: a systemic review.

Neurosurgical review, 43(1), 17-25.

Fiks, A. G., Jenssen, B. P., & Ray, K. N. (2021). A defining

moment for pediatric primary care telehealth. JAMA

pediatrics, 175(1), 9-10.

Fisk, M., Livingstone, A., & Pit, S. W. (2020). Telehealth

in the context of COVID-19: changing perspectives in

Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Journal of medical Internet research, 22(6), e19264.

Flodgren, G., Rachas, A., Farmer, A. J., Inzitari, M., &

Shepperd, S. (2015). Interactive telemedicine: effects

on professional practice and health care outcomes.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9).

Flores, A. P. D. C., Lazaro, S. A., Molina-Bastos, C. G.,

Guattini, V. L. D. O., Ump-ierre, R. N., Gonçalves, M.

R., & Carrard, V. C. (2020) Teledentistry in the

diagnosis of oral lesions: A systematic review of the

literature. JAMIA, 27(7), 1166-1172.

Fund, M. M. (2017). The Impact of Primary Care Practice

Transformation on Cost, Quality, and Utilization.

Gattu, R., Teshome, G., & Lichenstein, R. (2016).

Telemedicine applications for the pediatric emergency

medicine: a review of the current literature. Pediatric

emergency care, 32(2), 123-130.

Gogia, S. B., Maeder, A., Mars, M., Hartvigsen, G., Basu,

A., & Abbott, P. (2016). Unintended consequences of

tele health and their possible solutions: contribution of

the IMIA working group on telehealth. Yearbook of

medical informatics, (1), 41.

Helmer-Smith, M., Fung, C., Afkham, A., Crowe, L.,

Gazarin, M., Keely, E., & Liddy, C. (2020). The

feasibility of using electronic consultation in long-term

care homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors

Association, 21(8), 1166-1170.

Helou, S., El Helou, E., Abou-Khalil, V., Wakim, J., El

Helou, J., Daher, A., & El Hachem, C. (2020). The

effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on physicians’ use

and perception of telehealth: The case of Lebanon.

International journal of environmental research and

public health, 17(13), 4866.

Kaplan, B. (2020). Revisting Health Information

Technology Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues and

Evaluation: Telehealth/Telemedicine and COVID-19.

International journal of medical informatics, 104239.

Lavin, B., Dormond, C., Scantlebury, M. H., Frouin, P. Y.,

& Brodie, M. J. (2020). Bridging the healthcare gap:

Building the case for epilepsy virtual clinics in the

current healthcare environment. Epilepsy & Behavior,

111, 107262.

Telehealth: A Viable Option for Optimizing Health System Performance during COVID-19: Call to Action for Future Pandemics

287

Li, G., Fan, G., Chen, Y., & Deng, Z. (2020) What patients

“see” doctors in online fever clinics during COVID-19

in Wuhan?. JAMIA, 27(7), 1067-1071.

Liu, S. X., Xiang, R., Lagor, C., Liu, N., & Sullivan, K.

(2016). Economic modeling of heart failure telehealth

programs: when do they become cost saving?.

International journal of telemedicine and applications,

2016.

Lopo, C., Razak, A., Maidin, A., Rivai, F., Mallongi, A., &

Sesa, E. (2020). Technology impact on healthcare

quality of the hospital: A literature review. Enfermería

Clínica, 30, 81-86.

Lum, H. D., Nearing, K., Pimentel, C. B., Levy, C. R., &

Hung, W. W. (2020). Anywhere to anywhere: use of

telehealth to increase health care access for older, rural

veterans. Public Policy & Aging Report, 30(1), 12-18.

Lurie, N., & Carr, B. G. (2018). The role of telehealth in the

medical response to disasters. JAMA internal medicine,

178(6), 745-746.

Mehrotra, A., Paone, S., Martich, G. D., Albert, S. M., &

Shevchik, G. J. (2013). A comparison of care at e-visits

and physician office visits for sinusitis and urinary tract

infection. JAMA internal medicine, 173(1), 72-74.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur,

A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or

scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing

between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC

medical research methodology, 18(1), 1-7.

Nakagawa, K., & Yellowlees, P. M. (2019). The

physician’s physician: the role of the psychiatrist in

helping other physicians and promoting wellness.

Psychiatric Clinics, 42(3), 473-482.

Parisien, R. L., Shin, M., Constant, M., Saltzman, B. M., Li,

X., Levine, W. N., & Trofa, D. P. (2020). Telehealth

utilization in response to the novel coronavirus

(COVID-19) pandemic in orthopaedic surgery. JAAOS

Pisano, U. (2012). Resilience and Sustainable

Development: Theory of resilience, systems thinking.

European Sustainable Development Network (ESDN),

26, 50.

Polese, F., Carrubbo, L., Caputo, F., & Sarno, D. (2018).

Managing healthcare service ecosystems: Abstracting a

sustainability-based view from hospitalization at home

(HaH) practices. Sustainability, 10(11), 3951.

Qureshi, I. A., Raza, H., Whitty, M., & Abdin, S. Z. U.

(2015). Telemedicine implementation and benefits for

quality and patient safety in Pakistan. Knowledge

Management & E-Learning: An International Journal,

7(3), 367-377.

Ramsetty, A., & Adams, C. (2020) Impact of the digital

divide in the age of COVID-19. JAMIA, 27(7), 1147-

1148.

Schoenfeld, A. J., Davies, J. M., Marafino, B. J., Dean, M.,

DeJong, C., Bardach, N. S., & Dudley, R. A. (2016).

Variation in quality of urgent health care provided

during commercial virtual visits. JAMA internal

medicine, 176(5), 635-642.

Sheikh, A., Sood, H. S., & Bates, D. W. (2015). Leveraging

health information technology to achieve the “triple

aim” of healthcare reform. JAMIA, 22(4), 849-856.

Shockley, T. (2020). Telehealth and Achieving the

Quadruple Aim in Rural communities: A Vision for the

21st Century. Health Science Journal, 14(6), 1-3.

Sikka, R., Morath, J. M., & Leape, L. (2015). The quadruple

aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work.

Smith, W. R., Atala, A. J., Terlecki, R. P., Kelly, E. E., &

Matthews, C. A. (2020). Implementation guide for

rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the

American College of Surgeons, 231(2), 216-222.

Snoswell, C., Smith, A. C., Scuffham, P. A., & Whitty, J.

A. (2017). Economic evaluation strategies in telehealth:

obtaining a more holistic valuation of telehealth

interventions. Journal of telemedicine and telecare,

23(9), 792-796.

Steinman, M., Morbeck, R. A., Pires, P. V., Abreu Filho, C.

A. C., Andrade, A. H. V., Terra, J. C. C., ... &

Kanamura, A. H. (2015). Impact of telemedicine in

hospital culture and its consequences on quality of care

and safety. Einstein (Sao Paulo), 13(4), 580-586.

Tan, L. F. (2020). Ho Wen Teng V, Seetharaman SK, Yip

AW. Facilitating telehealth for older adults during the

COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: strategies from a

Singapore geriatric center. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 20,

993-995.

Thomas, E. E., Haydon, H. M., Mehrotra, A., Caffery, L. J.,

Snoswell, C. L., Banbury, A., & Smith, A. C. (2020).

Building on the momentum: Sustaining telehealth

beyond COVID-19. Journal of telemedicine and

telecare, 1357633X20960638..

Tuckson, R. V., Edmunds, M., & Hodgkins, M. L. (2017)

Telehealth. NEJM, 377(16), 1585-1592.

Turer, R. W., Jones, I., Rosenbloom, S. T., Slovis, C., &

Ward, M. J. (2020) Electronic personal protective

equipment: a strategy to protect emergency department

providers in the age of COVID-19. JAMIA, 27(6), 967-

971.

Vilendrer, S., Patel, B., Chadwick, W., Hwa, M., Asch, S.,

Pageler, N., & Sharp, C. (2020) Rapid deployment of

inpatient telemedicine in response to COVID-19 across

three health systems. JAMIA, 27(7), 1102-1109.

Waibel, K. H., Cain, S. M., Hall, T. E., & Keen, R. S.

(2017). Multispecialty synchronous telehealth

utilization and patient satisfaction within Regional

Health Command Europe: a readiness and recapture

system for health. Military medicine, 182(7), e1693-

e1697.

Winburn, A. S., Brixey, J. J., Langabeer, J., & Champagne-

Langabeer, T. (2018). A systematic review of

prehospital telehealth utilization. Journal of

telemedicine and telecare, 24(7), 473-481.

Wosik, J., Fudim, M., Cameron, B., Gellad, Z. F., Cho, A.,

Phinney, D., & Tcheng, J. (2020). Telehealth

transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care.

JAMIA, 27(6), 957-962.

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

288