Foreign Direct Investment as a Determinant of Digital Economy

Growth

José Botelho

1a

, Obidjon Khamidov

2b

, Olena Burunova

3c

, Volodymyr Kulishov

4d

and Ilyos Mamanazarov

5

1

Independent Researcher, Lisbon, Portugal

2

Bukhara State University, Uzbekistan

3

Jan Dlugosz University in Czestochowa, Poland

4

State University of Economics and Technology, Ukraine

5

Ministry of Economic Development and Poverty Reduction of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Uzbekistan

imamanazarov2020@mail.ru

Keywords: Digital Economy, Economic Recovery, Foreign Direct Investment, Innovation, Pandemic Crisis.

Abstract: The world economy crashed in 2020 due to pandemic crisis with a consequent collapse of global trade and

foreign direct investment (FDI). Digital economy links the society and the business environment, creates

qualified human capital and promotes innovation. Foreign direct investment in the digital economy powers

the digital economy and the digital economy increases the appetite for more foreign direct investment. Foreign

direct investment is key to supporting social and economic recovery and boosting the digital economy, and

conversely, the digital economy is key to increase foreign direct investment flows. The article analyses the

impact of foreign direct investment on digital economy and consequently on economic growth.

1 INTRODUCTION

The digital economy is defined as «the application of

Internet-based digital technologies to the production

and trade of goods and services» (UNCTAD, 2017, p.

156) or as «the economic activity that results from

billions of everyday online connections among

people, businesses, devices, data, and processes.

Digital economy is hyperconnectivity which means

connect people, organizations, and machines through

the Internet, mobile technology and the internet of

things (IoT)» (Deloitte, 2021).

The digital economy accelerates the economic

growth, links citizens to jobs and services, increases

the competitiveness of enterprises, generate new

opportunities for business and entry in new markets

and new e-value chains. The pervasiveness of the

digital economy brings new challenges related with

regulatory laws, social and developments impacts

(UNCTAD, 2017; WB, 2020).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4001-6563

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4902-759X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0502-0644

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8527-9746

The digital economy and investment are linked,

greater investment promotes more digital economy

and for a great digital economy, more investment is

needed. The digital economy has consequences on the

market activity of multinational enterprises (MNEs)

market activity due to the creation of new forms of

access to international markets and may have impacts

arising from the expansion of the physical network or

the opposite effect resulting in the expansion of

digital markets (UNCTAD, 2017).

FDI is defined as «an investment involving a long-

term relationship and reflecting a lasting interest and

control by a resident entity in one economy (foreign

direct investor or parent enterprise) in an enterprise

resident in an economy other than that of the foreign

direct investor (FDI enterprise or affiliate enterprise

or foreign affiliate)» (UNCTAD, 1997, p. 245). FDI

is fundamental to the rapid development of the digital

economy and this investment has impact on economic

growth (OECD, 2008).

76

Botelho, J., Khamidov, O., Burunova, O., Kulishov, V. and Mamanazarov, I.

Foreign Direct Investment as a Determinant of Digital Economy Growth.

DOI: 10.5220/0011341800003350

In Proceedings of the 5th International Scientific Congress Society of Ambient Intelligence (ISC SAI 2022) - Sustainable Development and Global Climate Change, pages 76-84

ISBN: 978-989-758-600-2

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

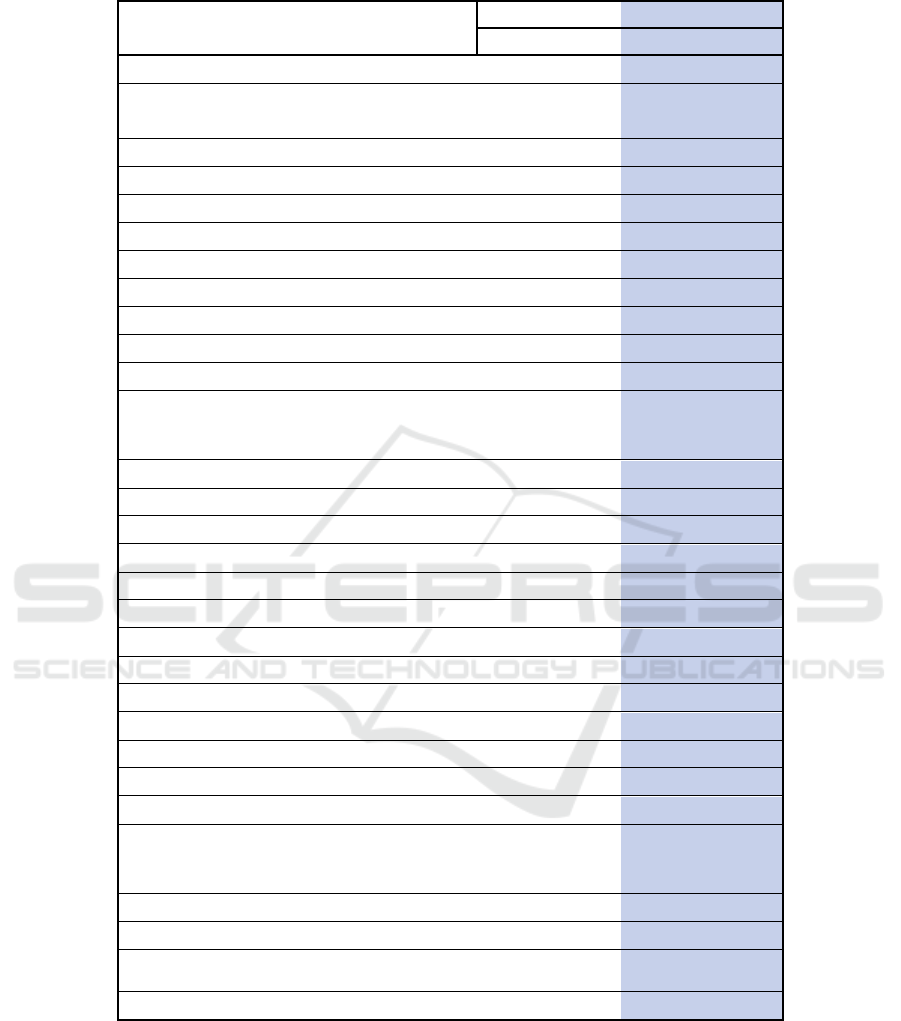

Table 1: Overview of the World Economic Outlook Projections.

Regions/Countries %

Projections (%)

2019 2020 2021 2022

World Output 2.8 –3.1 5.9 4.9

Advanced Economies 1.7 –4.5 5.2 4.5

United States 2.3 –3.4 6.0 5.2

Euro Area 1.5 –6.3 5.0 4.3

Germany 1.1 –4.6 3.1 4.6

France 1.8 –8.0 6.3 3.9

Italy 0.3 –8.9 5.8 4.2

Spain 2.1 –10.8 5.7 6.4

Japan 0.0 –4.6 2.4 3.2

United Kingdom 1.4 –9.8 6.8 5.0

Canada 1.9 –5.3 5.7 4.9

Other Advanced Economies [1] 1.9 –1.9 4.6 3.7

Emerging Market and Developing

Economies

3.7 –2.1 6.4 5.1

Emerging and Developing Asia 5.4 –0.8 7.2 6.3

China 6.0 2.3 8.0 5.6

India [2] 4.0 –7.3 9.5 8.5

ASEAN-5 [3]

4.9 –3.4

2.9 5.8

Emerging and Developing Europe 2.5 –2.0 6.0 3.6

Russia 2.0 –3.0 4.7 2.9

Latin America and the Caribbean 0.1 –7.0 6.3 3.0

Brazil 1.4 –4.1 5.2 1.5

Mexico –0.2 –8.3 6.2 4.0

Middle East and Central Asia 1.5 –2.8 4.1 4.1

Saudi Arabia 0.3 –4.1 2.8 4.8

Sub-Saharan Africa 3.1 –1.7 3.7 3.8

Nigeria 2.2 –1.8 2.6 2.7

South Africa 0.1 –6.4 5.0 2.2

Memorandum

World Growth Based on Market Exchange

Rates

2.5 -3.5

5.7 4.7

European Union 1.9 –5.9 5.1 4.4

Middle East and North Africa 1.0 –3.2 4.1 4.1

Emerging Market and Middle-Income

Economies

3.5 –2.3

6.7 5.1

Low-Income Developing Countries 5.3 0.1 3.0 5.3

[1] Excludes the Group of Seven (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United

Kingdom, United States) and euro area countries.

[2] For India, data and forecasts are presented on a fiscal year basis, and GDP from 2011

onward is based on GDP at market prices with fiscal year 2011/12 as a base year.

[3] Indonesia, Mala

y

sia, Phili

pp

ines, Thailand, Vietnam.

Foreign Direct Investment as a Determinant of Digital Economy Growth

77

The coronavirus crisis had a major impact on

economic growth, dragging economies into recession

in 2020. Despite negative growth in almost countries,

China grew by 2.3% due to the state financial support

(table 1).

The growth of the world economy dropped

significantly -3.1% in 2020, but projections for 2021

and 2022 are positive, 5.9% and 4.9%, respectively.

The economic growth projections by regions in 2021

and 2022 are:

Advanced economies fell -4.5% in 2020 and are

expected to grow 5.2% and 4.5% in 2021 and 2022,

respectively. The United States will lead the recovery

with economic growth projections of 6% and 5.2% in

2021 and 2022, respectively. The Euro Zone, with a

drop of -6.3% in 2020, will grow 5% and 4.3% in

2021 and 2022, respectively. Emphasis on growth

projections for 2021 and 2022 in the Eurozone for

Germany, France, Italy and Spain, with 3.1%, 4.6%;

6.3%, 3.9%; 5.8%, 4.2%; 5.7%, 6.4%, respectively.

Other advanced economies, such as Japan, United

Kingdom and Canada, will grow based on

projections, 2.4%, 3.2%; 6.8%, 5%; 5.7%, 4.9%,

respectively, in 2021 and 2022.

Emerging Market and Developing Economies fell

-2.1% in 2020 and are expected to grow 6.4% and

5.1% in 2021 and 2022, respectively. China is one of

the few countries in the world that did not have

negative growth in 2020 (+ 2.3%) and therefore China

will lead the recovery in emerging markets and

developing economies, along with India, with

economic growth projections 8% and 5.6% in 2021

and 2022, respectively, and India with economic

growth projections of 9.5% and 8.5% in 2021 and

2022, respectively.

ASEAN-5 (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines,

Thailand, Vietnam) fell -3.4% in 2020 and is

expected to grow 2.9% and 5.8%, according to

economic projections for 2021 and 2022,

respectively.

In Emerging and Developing Europe, the most

representative country is Russia which fell -3% and is

expected to grow 4.7% and 2.9% in 2021 and 2022,

respectively. T

In Latin America and the Caribbean, the most

representative countries are Brazil and Mexico, which

fell -4.1% and -8.3% in 2020, respectively, and the

economic growth projections for 2021 and 2022, for

Brazil are 5.2% and 1.5%, respectively, and for

Mexico 6.2% and 4%, respectively.

In the Middle East and Central Asia, the most

representative country is Saudi Arabia that fell -4.1%

in 2020 and the economic growth projections for

2021 and 2022 are 2.8% and 4.8%, respectively.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the most representative

countries are Nigeria, South Africa which fell -1.8%

and -6.4% in 2020, respectively, and the economic

growth projections for 2021 and 2022, for Nigeria are

2.6% and 2.7%, respectively, and for South Africa

5% and 2.2%, respectively.

2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVE AND

METHODOLOGY

The pandemic crisis has changed the world and the

digital economy is one of the challenges of the global

economy that can contribute to disrupt the way of

working and doing business. It is important to learn

from the new reality and discover new opportunities

in the post-pandemic economy, related with the

technology and digitization. Foreign direct

investment can help the digital economy development

to create new opportunities and contribute to

economic growth, removing obstacles and creating

new markets.

The objective of this study is to determine whether

FDI has an impact on the digital economy and,

consequently, on economic growth.

Based on several empirical review studies, this

study aims to understand the injection of foreign

direct investment into the economy and its

consequences on economic growth. The literature

review research method is adopted in this

investigation. The research includes a systematization

of several articles that are related to the theme of the

impact of FDI on the digital economy and,

consequently, on economic growth.

The study has a qualitative approach depending

on the context and objectives of the current research.

For this type of research, it is convenient to follow

qualitative research in order to better understand and

interpret the context, given the established objectives

(Ritchie, Nicholls & Ormston, 2013). Sources of

information come from various academic works,

books and publications.

3 LITERATURE REVIEW

The digital economy is disseminated by the internet

and associated technologies such as artificial

intelligence, blockchain, data analysis, cloud

computing and the internet of things (UNIDO, 2020).

The combination of these digital technologies created

a technological capability that experts called the

Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). The 4IR will

ISC SAI 2022 - V International Scientific Congress SOCIETY OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE

78

disrupt the way the global economy is structured

(UNCTAD, 2019). The Fourth Industrial Revolution

has immense potential to achieve inclusive and

sustainable industrial development and contribute to

create opportunities for developing and middle-

income countries with digitalization and

industrialization.

.

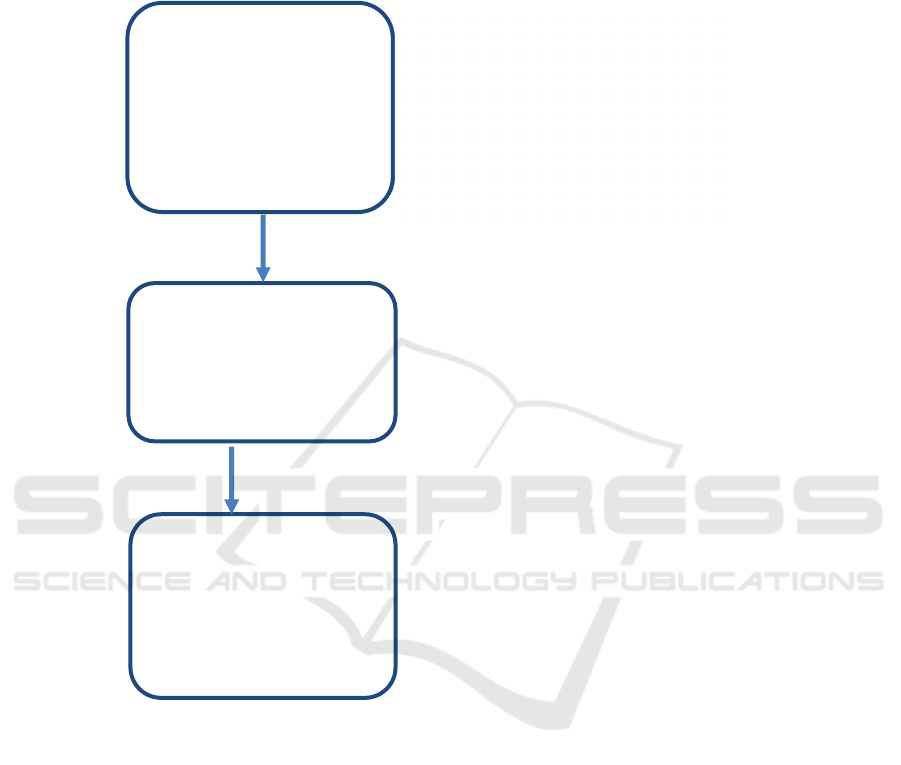

Figure 1: The Structure of Digital Economy.

The structure of the digital economy comprises

three dimensions (Figure 1). The narrow scope is

made up of the physical telecommunications and

internet infrastructure that includes cell phones,

laptops, fiber optic cables, telecommunications

towers, and the software that brings the infrastructure

to life. Associated with the narrow scope is the core

sector (IT / ICT) which has digital devices to connect

software applications to the broader economy, which

represents the delivery of the structured system. The

broader scope comprises businesses, governments,

institutions and consumers around the world who use

connectivity and products and services (UNCTAD,

2019).

The value of the digital economy and its potential

impact on the development of growth can lead to the

creation of new opportunities. Impacts can be

measured by indicators (gross domestic product

(GDP), employment, value added, income, trade) and

for each of the dimensions of the digital economy

(digitalized economy, digital economy and IT/ICT

sector).

Information and Communication Technologies

(ICTs) are considered one of the main engines of

economic growth, whose positive effects are

confirmed by different studies (Stanley,

Doucouliagos and Steel, 2018).

From a business perspective, digitalization and

infrastructure complemented by platforms and the

network can take the production of goods and

services to a higher level of quality. Its use will allow

for a better understanding of the customer and it will

CORE: DIGITAL

(IT/ICT) SECTOR

NARROW SCOPE:

DIGITAL ECONOMY

• Digital services

• Platform economy

BROAD SCOPE:

DIGITALIZED

ECONOMY

• e-Business

• e-Commerce

• Industry 4.0

• Precision agriculture

• Algorithmic economy

• Sharing economy

• Gig economy

• Gig factory

• Hardware manufacture

• Software & IT consulting

• Information services

• Telecommunications

Foreign Direct Investment as a Determinant of Digital Economy Growth

79

be possible to offer personalized products and

services.

As the main platforms belong to multinational

companies (MNEs) or digital (Evans & Gawer,

2016), the digital economy does not lead developing

countries to have more opportunities for national

companies (Foster et al., 2018).

To overcome this weakness, digital ecosystems

are the solution to support online platforms that allow

connecting companies, data and processes. Digital

ecosystems in developing countries are national start-

ups, such as service and payment providers (Bukht &

Heeks, 2017).

Digital platforms, which are called «digital

business ecosystems» (Sussan & Acs, 2017), can

promote lower transaction costs, create more

opportunities, open new markets, reduce barriers to

entrepreneurship and increase funding for start-ups

(Lehdonvirta et al., 2018).

For society, through digital platforms, individuals

have a choice with a greater diversity of goods and

services, eventually customized, delivered faster and

at lower costs. The digital economy, in developing

economies, can create new highly skilled jobs,

particularly in the digital sector and associated areas

that require technical and analytical skills (WB,

2018).

The government will benefit from greater

digitalization through increased tax collection due to

increased productivity that will lead to increased

economic activity. Furthermore, new benefits for the

government may be the use of data for the

development of society and for the solution of

society's problems. The management of data can help

in solving global matters related with human health,

natural environment, improve efficiency of resources

and with businesses and civil society. In addition, the

United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable

Development could benefit from digital data as this

can help to compile indicators that support the agenda

(MacFeely, 2019).

Platforms may be a marketplace for businesses

where companies can access to foreign markets

through e-commerce. More broadly, the digitalization

of the economy can lead to a new level of efficiency

and, in the future, to changes in established sectors in

developing countries. With greater efficiency and

automation of production, work in developing

countries can disappear or, alternatively, be

«relocated» back to more advanced economies

(Banga and Willem, 2018; Hallward-Driemeier and

Nayyar, 2018).

The digital economy has its drawbacks for small

businesses and the brick-and-mortar industries, who

find it hard to fight big online stores like amazon.com.

Digitalization can have negative consequences in

terms of job losses and increasing inequality. In

addition, digital platform owners can apply tax

optimization, which will negatively impact

government tax collection. Finally, there are new

concerns related to privacy, security, democracy and

ethical issues (Couldry & Mejias, 2018; Mayer-

Schönberger & Ramge, 2018).

From an international point of view, the impacts

on trade may be insufficient and will depend on the

country's degree of development, its commercial

structure and its level of digitization. Developing

countries may not fully enjoy the benefits of

digitalization and become dependent on global digital

platforms.

Investing in certain sectors of the digital economy

of developing countries providing digital platforms

for transacting can have consequences on the nature

of transactions and in the ability of companies to

expand rapidly, affecting sector structure model.

Analysing the nature of transactions the trend is to

change from a «pipeline» models to models where

platforms are being used (Van Alstyne et al. 2016). In

pipeline models, goods and services are produced and

«pushed» to the customer through several phases

which add value while in platform models companies

and individuals can enter easily and provide various

products and services to customers (Cusumano &

Gawer, 2002). Therefore, in the platform economy,

traditional supply and demand (and production and

consumption) no longer apply. The structure of the

new economic model assumes a circular shape as a

simultaneous sending and receiving cycle in which

data and interactions constitute the main resource and

source of value. In fact, in the digital economy, what

dominates is an omni-channel approach and as the

digital transition takes place, production and

transaction processes can be established in different

contexts between the physical and virtual world and

can be purely physical or digital or a combination of

both.

The platform economic models allow companies

to achieve economies of scale faster. The platform

offers to the different parties the possibility of

carrying out transactions as a «marketplace» and, in

this sense, is a «physical asset light». The global

expansion and dominance of so-called ride-sharing

platforms demonstrate this fact. The platforms have a

very low investment due to the lack of goods (taxis)

and no employees (drivers are hired) and, therefore,

scale up is faster with lower costs (Parker et al.,

2016).

There is a risk of expansion of the «physical light

asset», as the platform's competitors can offer lower

ISC SAI 2022 - V International Scientific Congress SOCIETY OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE

80

costs and, consequently, users can easily change

supplier. To avoid this practice, platform owners can

restrict some activities, adopting non-competitive

procedures (Parker et al., 2016). Platforms represent

a major shift in the digital economy, where platforms

are the foundation of the value sharing framework.

Platform owners are interested in boosting the

market by allowing the entry of large small

companies and end users to create more opportunities

in developing countries and, at the same time, digital

companies can appear to support platform models.

Platform owners are interested in driving the

market, allowing the entry of large small businesses

and end users to create more opportunities in

developing countries, and at the same time, digital

companies can appear to support platform models.

However, there is a real risk that the platform will be

closed and the platforms will reinforce their power

creating unfavourable conditions for companies and

individuals. This is primarily an issue for small

businesses or individuals who may feel that they are

dependent on a particular platform that offers few

alternatives under unfavourable conditions.

Thus, it seems that the best strategy for

developing countries is for digital companies to adopt

platform models and drive local businesses,

competing with global digital platforms. However,

the distribution of results can be uneven between

onwers and users and large platforms can charge large

costs and provide few market opportunities and,

therefore, companies must analyse the costs and

market opportunities and decide to maintain or move

to another platform. Several studies suggest that

digital platforms can support small businesses in

developing countries to conquer new markets (eBay,

2013). However, researchers can help identify the

trajectories of these companies on digital platforms.

At the same time, it is very important to identify the

value creation that is being done by these digital

companies in developing countries so that it is

possible for policy makers to understand and

conclude about the economic consequences of digital

platforms.

In the modern economy, value is shared between

companies operating through networks and supply

chains. The value is measured by analysing prices,

incomes, profits, gender balance. Developing

countries must analyse and decide to outsource core

activities and focus on their competencies (Prahalad

and Hamel, 1990). Activities in developing countries

of lesser value, such as goods or services produced

and less labour intensive, should be disregarded

(Gereffi, 1994). In addition, a study of workforce

outcomes shows that employees who are in the

process of creating value often have low wages and

occupy unstable positions (Berg et al., 2018). If low-

value activities grow, this will lead to negative

outcomes across the economy and hence value

distribution can be considered to review policy

options.

Governments are key in the process of defining

strategies to attract FDI into digital economy. They

must encourage the attraction of FDI to the digital

economy by three ways. First, they have to build the

policy and regulatory archetype to protect

stakeholders and national interests. Second, the rules

for foreign participation must be clearly defined in to

maximize the investors involvement. Third, they

must have an active involvement that allows

governments to find investors with digital economy

projects (UNCTAD, 2019). Foreign direct investment

in the digital economy contributes to economic

growth and economic growth benefits from the

development of the digital economy (UNCTAD,

2019). The question that arises is whether FDI has an

impact on economic growth.

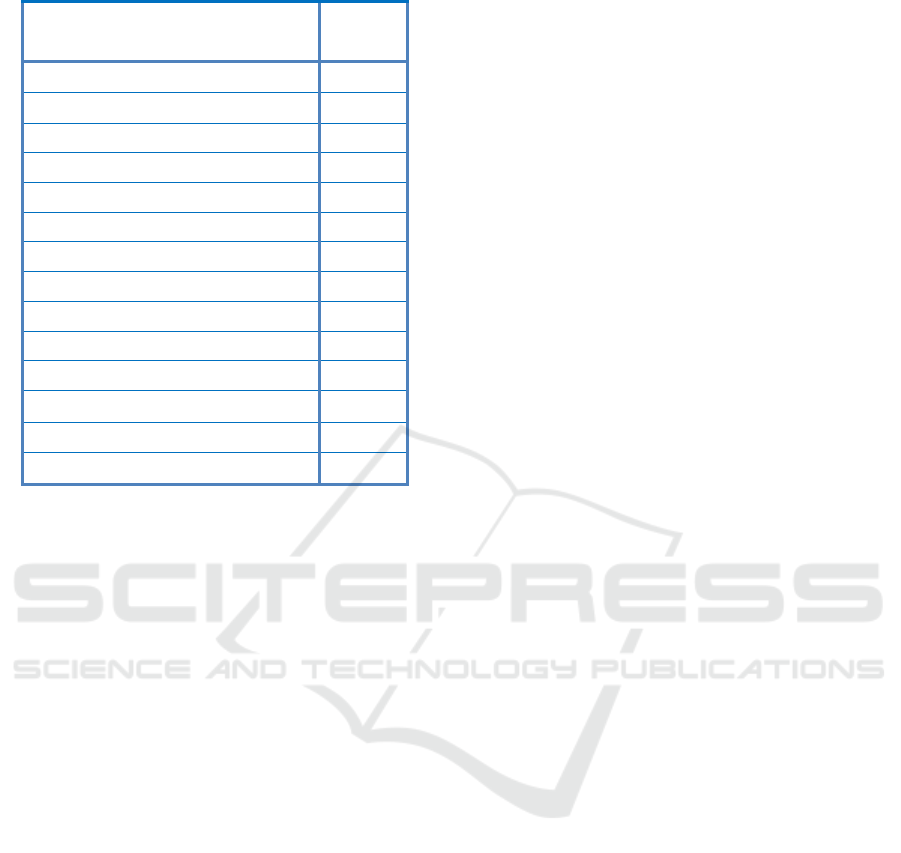

Several studies concluded that there is a positive

relationship between FDI and economic growth (table

2).

Muse (2021) analysed the impact of FDI on

Ethiopia's economic growth. Muse finds that FDI has

a positive impact on Ethiopia's economic growth in

the short and long term, and that human capital and a

stable macroeconomic environment converge on FDI

economic growth. To attract more FDI, Ethiopia has

to invest in human capital and needs to restructure the

financial sector.

Ayamba (2020) investigated the impact of FDI on

sustainable development in China and concludes that

FDI helps financial deficits. Low financial deficit will

contribute to a stable macroeconomic environment

and, therefore, to economic growth.

Florina (2020) concluded that FDI is a strategic

factor that contributes to a country's economic

development and that there is a correlation between

the volume of FDI flows and a country's development

potential.

Alzaidy (2017) investigated the impact of FDI on

Malaysia's economic growth during the period 1975-

2014 and concludes that FDI plays a key role in

Malaysia's economic growth. The financial sectors

are well developed and must lead and facilitate FDI

overflows to boost economic growth.

Lessmann (2013), based on a panel data set of 55

countries, concluded that FDI is an important

determinant of economic growth.

Foreign Direct Investment as a Determinant of Digital Economy Growth

81

Table 2: Studies over FDI Impact on Economic Growth.

Researchers Ano

Muse 2021

Ayamba 2020

Florina 2020

Alzaidy 2017

Lessmann, C. 2013

Kentor & Jorgenson 2010

Iwona 2010

Al-Iriani & Al-Shamsi 2009

Mengistu & Adams 2007

Andreas 2006

Lumbila, K. 2005

Sylwester 2005

Bengoa & Sanchez-Robles 2003

Hermes & Lensink 2003

Kentor & Jorgenson (2010) explored the impact

of FDI from foreign subsidiaries on economic growth

in less developed countries between 1970 and 2000.

They concluded that foreign subsidiaries had a

positive effect on economic growth in less developed

countries.

Iwona (2010) investigated the influence of FDI on

countries’ economies and concluded that FDI brings

capital, new technologies, know-how and

management skills. Poland is an excellent example of

a FDI host country with a coherent policy for foreign

investment and a favorable environment for investors.

Al-Iriani & Al-Shamsi (2009) studied the

association between FDI and economic growth in the

six countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council

(Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and

the United Arab Emirates). FDI was identified as a

determinant of economic growth through its role in

technological diffusion.

Mengistu & Adams (2007) examined the

influence of FDI on economic growth in 88

developing countries and concluded that FDI is

positively correlated with economic growth. The

study also found that a country's institutional

infrastructure is positively correlated with economic

growth.

Andreas (2006) analysed the potential of FDI

inflows to affect host country economic growth. The

paper carried out a cross-sectional and panel data

analysis of a dataset of 90 countries in the period

1980-2002 and concluded that FDI inflows impact in

developing economies but not developed economies.

Lumbila (2005) conducted an analysis of the

impact of FDI on economic growth using data from

47 African countries and concluded that FDI has a

positive impact on economic growth in Africa. The

study also concluded that qualified human capital, a

favourable investment environment, lower country

risk and a stable macroeconomic environment are

factors that contribute to the impact of FDI on

economic growth.

Sylvester (2005) examined the impact of FDI on

economic growth in less developed countries and

concluded that FDI is positively associated with

economic growth in this sample of countries.

The study by Bengoa & Sanchez-Robles (2003)

concluded that it is a positive relationship, but only if

the host country has several dimensions fulfilled

(level of education, technology, human capital,

political stability).

The study of Hermes & Lensink (2003) suggests

that FDI has a positive impact on economic growth

when the host country has a financial system

sufficiently developed.

4 CONCLUSIONS

After the 2020 crash, the post-pandemic crisis

presents challenges. Even with the pandemic

escalating again and its duration unknown, there may

be a need for ongoing health care costs. At the same

time, in several countries, public finances will face

high levels of debt and, to be sustainable, they need

strong policies to facilitate growth and address

opportunities related to green technology and

digitalization.

Investment in digital economies is needed and

governments have a fundamental role in the process

of institutionalizing the policy and regulatory

framework in order to protect national and foreign

interests. Furthermore, governments must invest in

broadband to bring internet access to everyone and

close the gap between those who have access and

those who don't.

Foreign direct investment is a key financial

instrument to improve the digital economy and

therefore increase economic growth.

Analysing several studies carried out in

different countries and times, it is possible to

conclude that there is a positive influence of FDI on

economic growth and, therefore, on the digital

economy. To attract FDI into the digital economy and

bring economic growth, these studies suggested that

ISC SAI 2022 - V International Scientific Congress SOCIETY OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE

82

governments should create a FDI framework that

contains attractive factors for investors, such as a

stable macroeconomic environment, a high level of

education, a skilled workforce, procedures to make

doing business easier, political stability and a strong

financial sector.

REFERENCES

Al-Iriani, M. & Al-Shamsi, F., 2009. Foreign direct

investment and economic growth in the GCC countries:

A causality investigation using heterogeneous panel

analysis. Available at:

https://meea.sites.luc.edu/volume9/PDFS/Al-

Iriani%20-%20paper.pdf, accessed in 13.12.2021.

Alzaidy, G, Ahmad & Mohd Naseem Bin Niaz, 2017. The

Impact of Foreign-direct Investment on Economic

Growth in Malaysia: The Role of Financial

Development. International Journal of Economics and

Financial Issues, Vol 7, Iss 3, Pp 382-388.

Andreas, J., 2006. «The Effects of FDI Inflows on Host

Country Economic Growth», CESIS - Electronic

Working Paper Series

Ayamba, E.; Haibo, C.; Abdul-Rahaman, A-R.; Serwaa, O.

and Osei-Agyemang, A., 2020. The impact of foreign

direct investment on sustainable development in China.

Environmental Science and Pollution Research, Jul.;

27; 20; p25625-p25637.

Banga, K. & Willem, D., 2018. Digitalisation and the future

of manufacturing in Africa. Overseas Development

Institute, London.

Bengoa, M., & Sanchez-Robles, B., 2003. Foreign direct

investment, economic freedom and growth: new

evidence from Latin America. European Journal of

Political Economy, 19, 529–545.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0176-2680(03)00011-9,

available at:

http://ciberoamericana.com/documentos/BengoaySanc

hez-Robles%5B2003%5D.pdf, accessed in 14.12.2021.

Berg, J., Furrer, M., Harmon, E., Rani, U. and Silberman,

M., 2018. Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of

Work: Towards Decent Work in the Online World.

International Labour Organisation, Geneva

Bukht, R. & Heeks, R., 2017. Defining, conceptualising and

measuring the digital economy. GDI Development

Informatics Working Papers, no. 68. University of

Manchester, Manchester

Couldry, N. & Mejias, U., 2018. Data colonialism:

Rethinking big data’s relation to the contemporary

subject. Television & New Media. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476418796632.

Cusumano, M. and Gawer, A., 2002. The elements of

platform leadership. MIT Sloan Management Review,

43(3): 51–58.

Deloitte, 2021. What is digital economy? Unicorns,

transformation and the internet of things.

Available from:

https://www2.deloitte.com/mt/en/pages/technology/art

icles/mt-what-is-digital-economy.html, accessed in

10.12.2021.

eBay, 2013. Commerce 3.0 for development: The promise

of the Global Empowerment Network. San Francisco,

CA. Available from:

https://www.ebaymainstreet.com/sites/default/files/eB

ay_Commerce-3-for-Development.pdf.

Evans, P. & Gawer, A., 2016. The rise of the platform

enterprise: A global survey. The Emerging Platform

Economy Series, 1. The Centre for Global Enterprise,

New York, NY.

Foster, C., Graham, M., Mann, L., Waema, T. and

Friederici, N., 2018. Digital control in value chains:

Challenges of connectivity for East African firms.

Economic Geography, 94(1): 68–86

Florina, P., 2020. Some aspects regarding the impact of

foreign direct investment in economic development.

Studies & Scientific Research: Economics Edition,

2020, Issue 31, p70-78, 9p. Publisher: Vasile

Alecsandri University of Bacau, Faculty of Economic

Sciences.

Gereffi, G., 1994. The organization of buyer-driven global

commodity chains: How US retailers shape overseas

production networks. In: Gereffi G and Korzeniewicz

M, eds. Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism.

Praeger, Westport, CT: 95–122.

Hallward-Driemeier, M. & Nayyar, G., 2018. Trouble in the

Making? The Future of Manufacturing-Led

Development. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Hermes, N., & Lensink, R., 2010. Foreign direct

investment, financial development and economic

growth. Journal of Development Studies, 40(1), 142–

153.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331293707,

available at:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/002203

80412331293707?needAccess=true, accessed in

14.12.2021.

Iwona, N., 2010. The impact of foreign direct investment

on economic development in Poland. Human

Resources: The Main Factor of Regional Development.

2010, Issue 3, p129-133. 5p.

Kentor, J. & Jorjenson, A., 2010. Foreign Investment and

Development: An Organizational Perspective. Sage

Journals – International Sociology.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580909360299.

Lehdonvirta, V., Kässi, O., Hjorth, I., Barnard, H. and

Graham, M., 2018. The global platform economy: A

new offshoring institution enabling emerging-economy

microproviders. Journal of Management, 45(2): 359–

383.

Lessmann, C., 2013. «Foreign direct investment and

regional inequality: A panel data analysis», China

Economic Review 24, 129–149

Lumbila, K.N., 2005. «What makes FDI Work? A Panel

Analysis of the Growth Effect of FDI in Africa», Africa

Region Working Paper Series No. 80, available at:

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/1087514

68002680983/pdf/331190PAPER0wp80.pdf, accessed

in 14.12.2021.

Foreign Direct Investment as a Determinant of Digital Economy Growth

83

MacFeely, S., 2019. The big (data) bang: Opportunities and

challenges for compiling SDG indicators. Global

Policy. Wiley online library, volume 10 - supplement 1.

January.

Mayer-Schönberger, V. & Ramge, T., 2018. Reinventing

Capitalism in the Age of Big Data. John Murray,

London.

Mengistu, B., & Adams, S., 2007. Foreign direct

investment, governance and economic development in

developing countries. The Journal of Social, Political,

and Economic Studies, 32(2), 223, available at:

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10

.1.1.680.6234&rep=rep1&type=pdf, accessed in

14.12.2021.

Muse, N. & Mohd, S., 2021. Impact of Foreign Direct

Investment in Ethiopia. In: Latin American Journal of

Trade Policy, Vol. 4, Nº. 10 (Ejemplar dedicado a:

LAJTP Vol 4 N° 10), pages 56-77 Language: English,

Base de dados: Dialnet

OECD, 2008. Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development. Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct

Investment, fourth edition. Available from:

https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investmentstatisticsanda

nalysis/40193734.pdf, accessed in 14.12.2021

Parker, G., Alstyne, M. and Choudary, S., 2016. Platform

Revolution: How Networked Markets are Transforming

the Economy – And How to Make Them Work for You.

1st edition. W. W. Norton & Company, New York, NY.

Prahalad, C. and Hamel, G., 1990. The core competence of

the corporation. Harvard Business Review, (May–

June): 3–22.

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R.

(Eds.)., 2013. Qualitative Research Practice:

Satyanand, N., 2021. Foreign Direct Investment and the

Digital Economy. ARTNeT on FDI Working Paper

Series, No. 2, July 2021, Bangkok, ESCAP.

Stanley T., Doucouliagos H. and Steel P., 2018. Does ICT

generate economic growth? A meta-regression

analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys, 32(3): 705–

726.

Sussan, F. & Acs, Z., 2017. The digital entrepreneurial

ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 49(1): 55–73.

DOI 10.1007/s11187-017-9867-5

Sylwester, K., 2005. Foreign direct investment, growth, and

income inequality in Less Developed Countries.

International Review of Applied Economics, 19(3),

289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02692170500119748,

available at:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/026921

70500119748, accessed in 14.12.2021.

UNCTAD, 1997. United Nations Conference on Trade and

Development. World Investment Report 1997:

Transnational Corporations, Market Structure and

Competition Policy (Geneva and New York: United

Nations), United Nations publication, available from:

https://unctad.org/system/files/official-

document/wir2007_en.pdf, accessed in 14.12.2021.

UNCTAD – United Nations Conference on Trade and

Development, 2017. World Investment Report.

Available from:

https://unctad.org/system/files/official-

document/wir2017_en.pdf, accessed in 10.12.2021.

UNCTAD – United Nations Conference on Trade and

Development, 2019. Value Creation and Capture:

Implications for Developing Countries. Available from

https://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?

publicationid=2466, accessed in 14.12.2021.

UNIDO – United Nations Industrial Development

Organization, 2020. Industrial Development Report

2020: Industrializing in the Digital Age. Available from

https://www.unido.org/resources-publications-

flagshippublications-industrial-development-report-

series/idr2020, accessed in 14.12.2021.

Van Alstyne, M., Parker, G. and Choudary, S., 2016.

Pipelines, platforms, and the new rules of strategy.

Harvard Business Review, 94(4): 54–62.

WB – World Bank, 2018. Information and

Communications for Development 2018: Data-Driven

Development. Washington, DC. Available from:

file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/9781464813252.pdf,

accessed in 26.12.2021.

WB – World Bank, 2019. The Digital Economy in

Southeast Asia Strengthening the Foundations for

Future Growth. Available from:

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handl

e/10986/31803/The-Digital-Economy-in-Southeast-

Asia-Strengthening-the-Foundations-for-Future-

Growth.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, accessed in

16.12.2021.

WB – World Bank, 2020. Digital Development Global

Practice. Available from:

https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/digitaldevelopme

nt, accessed in 10.12.2021.

ISC SAI 2022 - V International Scientific Congress SOCIETY OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE

84