State of Knowledge-based Management in Project Networks: Case in

Finnish Infrastructure Construction Sector

Viivi Siuko

a

, Jussi Myllärniemi

b

and Pasi Hellsten

c

Tampere University, Kalevantie 4, 33014 Tampere, Finland

Keywords: Project Networks, Knowledge-based Management, Maturity Model.

Abstract: Finnish infrastructure construction sector has challenges in productivity and advancing digitalization. We

suggest that these problems can be explained with inadequate knowledge-based management (KBM)

practices: When information goes missing, employees must collect the information repeatedly. When

organizations haven’t identified their information needs, data is collected but never used. The purpose of this

research is to discover what is the priority of development to improve KBM in project network. A project

network in Finnish infrastructure construction sector typically consists of project companies and public

customers. This research was conducted by distributing a survey on maturity of KBM to 22 Finnish

organizations in infrastructure construction. 10 of these organizations are customer organizations and 12 are

project companies. The results are analyzed with a framework suggested for the maturity survey. The results

show that, in the project network, customer organizations have less developed KBM practices than project

companies, which is not surprising. The interesting point, however, is that the results highlight the importance

of the customer organizations in information sharing in the project network. Therefore, the inadequate KBM

practices of customer organizations seem to weaken the productivity of the whole project network.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digitalization is a breakthrough way of operating in

many fields affecting our daily operations as the

organizations need to consider their effectiveness and

competitive edge in relation to their counterparts.

This has been so already for many years (Lindgren et

al. 2019). Digitalization, with its many novel tools

and functions enable faster operating, better handling,

more efficient time consumption, and improved

information availability (Parviainen et al. 2017,

Isaksson et al. 2018).

The need for productivity improvements, seen

also in the infrastructure construction sector,

necessitates the efficient utilization of knowledge

resources to improve organisations’ decision-making

and advance digitalization. Several studies show that

amount of available data or information is not an issue

(e.g. Myllärniemi et al. 2019). However, the

organisations need to practice knowledge-based

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7368-2610

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2846-0426

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7602-1690

management, as in determine which information is

relevant, how to make information more useful and

meaningful, and how to use it in decision-making

(Kaivo-oja et al. 2015; Choo 1998). Optimizing the

use of existing knowledge in order to make the best

of it helps organisations, for example, to enhance its

decision-making and knowledge processes.

Infrastructure covers commodities provided for

public use (Kasper 2015), including roads and

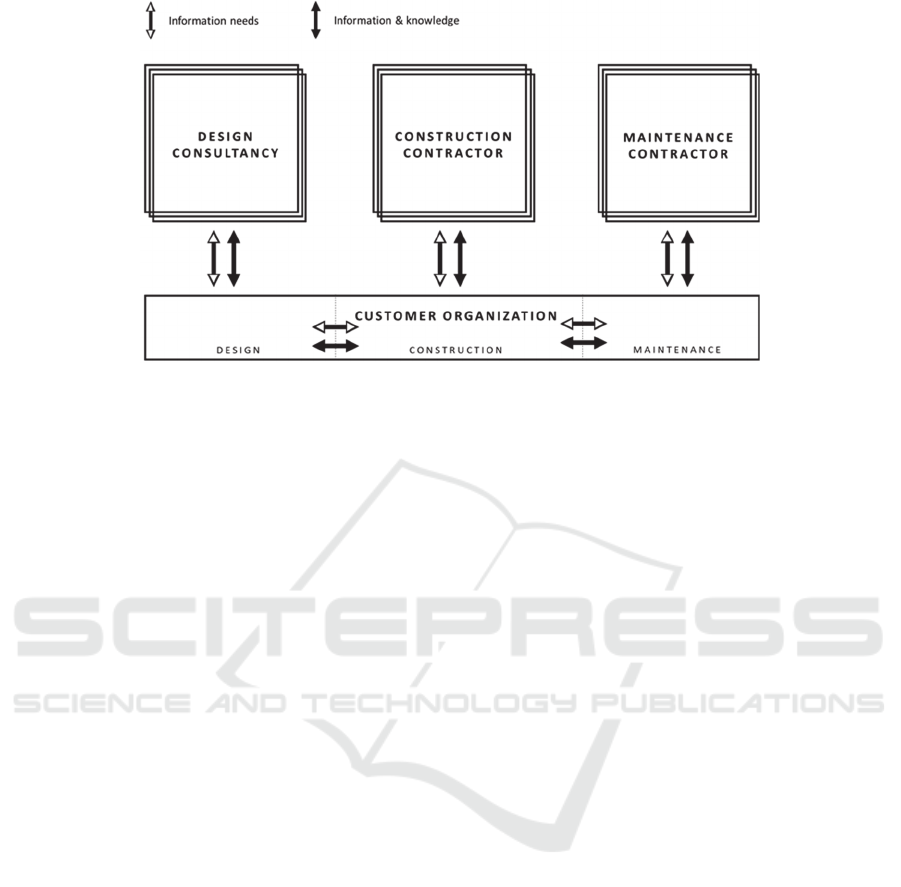

bridges. As described in figure 1, in Finnish

infrastructure construction sector the customer

organization typically orders infrastructure design

from design consultancies, and infrastructure

construction and maintenance from contractors. The

information needs and information are shared in the

network mainly through the customer organization.

The customer organization can have multiple projects

on going simultaneously with different consultancies

and contractors, which makes the project network

even more complex. Larsson et al. (2013) report a

similar infrastructure construction process in Sweden.

126

Siuko, V., Myllärniemi, J. and Hellsten, P.

State of Knowledge-based Management in Project Networks: Case in Finnish Infrastructure Construction Sector.

DOI: 10.5220/0011376300003335

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2022) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 126-133

ISBN: 978-989-758-614-9; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Figure 1: Project network in infrastructure construction sector.

To research digitalization and productivity

challenges in infrastructure construction we answer

the question “How is knowledge-based management

perceived and dealt with in Finnish public sector

project networks?” by studying KBM in project

networks in large Finnish cities. We also offer some

propositions to solve the challenges and make some

generalizations regarding the approach to these issues

to be considered also in larger extent. In next chapter

the related research is illuminated. Chapter three

shows how the study is conducted and how the

material was gathered. Chapter four presents the

results. Chapter five discusses the meaning of the

previous, and chapter six concludes the research.

This research provides new knowledge on KBM

in project networks. Research on interorganizational

KM or KBM in project networks is quite narrow

(Agostini et al. 2020). This research took a quite wide

perspective on KBM, not focusing only on

information sharing or protection. In addition, we

focus on a specific type of project network in which

customer organization has a key role. The

practitioners can derive ideas for developing KBM in

their project network, whether they represent a

customer organization or a project company.

2 RELATED RESEARCH

2.1 Knowledge-based Management

Factors, such as reducing resources, citizens’

expectations, and public pressure give the need to

constantly develop the operations (Gunasekaran

2005; Hellsten and Pekkola 2019). In today’s public

sector, the objective for KM is to provide means to

better understand the needs of the people on all levels

but also to offer the inhabitants of the city with better

and more inclusive services in the most resource-

efficient and sustainable way, in addition to mere

improving the operation. (Hellsten et al. 2021).

According to Wiig (1997) knowledge management

(KM) aims to improve organizations' effectiveness

and performance by stressing the importance of

knowledge creation, development, management, and

finally, leveraging. KM is an umbrella term of

understanding, defining and utilizing available

knowledge that provides the decision-makers a useful

tool for managing their organizations (Moss 1999).

KBM, on the other hand, is defined as an approach in

which organisational knowledge assetts, including

data, information and knowledge, is processed and

utilised to support decision-making. KBM is about

KM policies, practices and processes that are

understood as managerial practices designed to

support effective and productive information

management for the benefit of the organisation

(Inkinen 2016). Jalonen (2015) says it aims to reduce

uncertainty due to lack of information and to manage

the ambiguity arising from the amount of

information.

Knowledge is processed from data through

information into knowledge. One way to structure

knowledge process is the process model of

information management created by Choo (2002).

The model consists of six phases. It starts by defining

information needs to later be satisfied as efficiently as

possible by information acquisition from both

internal and external information sources. The

model’s third phase is information organisation and

storing. The following phases relate to information

analysis for systematic and advanced information

products or service, information sharing and usage.

State of Knowledge-based Management in Project Networks: Case in Finnish Infrastructure Construction Sector

127

After the latter, possible changes in the organisational

activities take place and the cycle starts over.

Choo’s model forms a basis for Jääskeläinen et

al.’s (2022) maturity model designed for information

and knowledge management (IKM) in public sector.

The IKM expands Choo’s model from both the

technical side of information handling and the

utilization of the information by humans

(Jääskeläinen et al. 2022). Jääskeläinen et al. add

sections called Vision & strategy and Governance and

organisation to their model. The IKM offers useful

and practical way to determine the state of an

organization’s information and knowledge

management and identify development needs

(Jääskeläinen et al. 2022). Later on Choo’s model

phases are called sections which consist of KBM

practices.

2.2 Knowledge-based Management in

Project Network

Projects are temporary systems formed by individuals

or organizational actors to accomplish complex and

unique tasks (Lundin & Söderholm 1995; Obstfeld

2012). An interorganizational network working on a

common project can be called a project network (Alin

et al. 2013). Because of the complexity, uniqueness,

and uncertainty of project activities, they require

increased focus on KBM (Ajmal et al. 2010). Projects

involving multiple organizations have become

increasingly important (Bakker 2011) which creates

additional challenges for knowledge sharing:

organizations need to balance between the risks and

benefits of knowledge sharing, the information

systems might be misaligned, and employees might

not share their knowledge in the network (Vuori et al.

2019).

Riege (2005) has identified dozens of barriers for

knowledge sharing, in individual, organizational and

technological levels. These barriers include e.g., lack

of time, low awareness on the value of the knowledge

possessed, fear of losing expert status when sharing

knowledge, differences in experience levels, lack of

leadership, missing integration of KM strategy and

business strategy, internal competitiveness,

inadequate IT systems, a mismatch with employees

needs and the tools, and lack of training. Vuori et al.

(2019) built on Riege’s (2005) model with the

purpose to leverage it to network level. They found

that Riege’s barriers are relevant in the network level

and there are also network-specific barriers in

addition. They suggest that geographical or cultural

distance, strength of the organizational ties and trust,

value positioned on the interorganizational

knowledge all have an important role in the network

level.

Knowledge-based theory argues that

organisations’ success depends strongly on their

knowledge-based resources (Grant, 1996; Spender

and Grant, 1996). The early studies on KM focused

on the intra-organizational level (Nonaka 1994,

Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995, Grant 1996). The interest

for interorganizational KM or KBM in networks has

followed as the value of interorganizational

relationships for accessing and combining knowledge

has been recognized (e.g., Buckley et al. 2009).

External partners have an increasingly important role

in filling internal knowledge gaps (Bojica et al. 2018)

and to benefit from the knowledge partners acquire,

organizations need to manage and align inbound

knowledge flows with the internal activities

(Brunswicker and Vanhaverbeke 2015). KBM in

networks has become increasingly important, as it can

be defined as managing the acquisition, sharing, and

co-creation of knowledge between organizations

(Lancini 2015), which enables organizations to

benefit from the knowledge in the network.

The focus on interorganizational KM research has

been narrow, concentrating mainly on specific types

of interorganizational relationships, knowledge

transfer among organizations and on knowledge

protection (Agostini et al. 2020). There are challenges

in capturing and reusing knowledge produced in

projects, and in utilizing the lesson’s learned.

Bhargav and Koskela (2009) suggest that KBM in

project networks can be effective in capturing project-

based knowledge, if it includes top management

support, an easy-to-use KM system, and creating the

right environment for knowledge sharing. The

strategies for knowledge management, information

technology and business need to be aligned to achieve

KBM objectives (Wang and Wang 2009). As

Omotayo (2015) puts it, if people are willing to share

knowledge, technology can enable a further reach.

However, applied tools and systems only won’t get

people to share their knowledge.

3 METHODS

The research was conducted by distributing a

maturity survey on KBM to 22 Finnish organizations

in infrastructure construction sector. These

organizations represent the three stages of

infrastructure construction: design, construction and

maintenance. 10 of these organizations are customer

organizations and 12 are project companies. In total,

we received 68 responses to this survey. The survey

is based on maturity survey on information and

knowledge management by Jääskeläinen et al.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

128

(2022). The survey includes eight different sections

on KBM: vision and strategy of an organization (A),

governance and organization of a project (B),

information needs in a project (C), information

acquisition in a project (D), information organization

and storage in a project (E), information products in a

project (F), information and knowledge sharing in a

project (G) and information usage in a project (H).

Each of these sections included between five and ten

statements on the development of practices. In

addition, each section included one statement

concerning the satisfaction to these practices. The

respondents chose in Likert scale if they strongly or

somewhat disagreed, neither disagreed nor agreed,

somewhat or strongly agreed, or didn’t want to

respond the statement. In addition, each section

included an open question, where respondents could

describe their thoughts more freely.

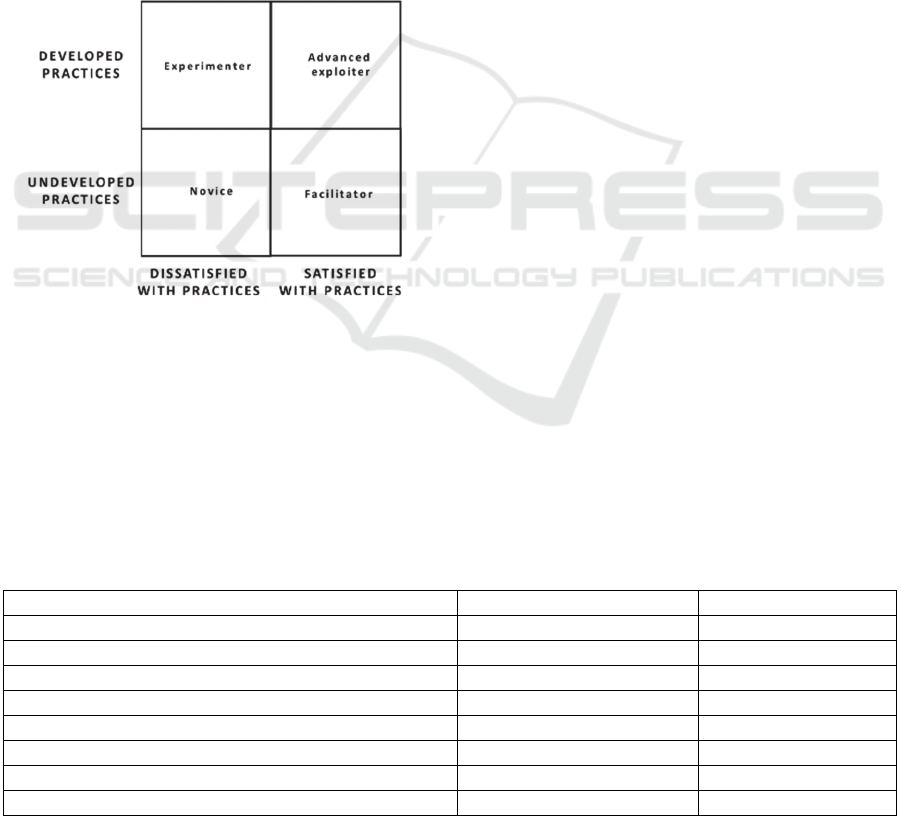

Figure 2: A framework for analyzing maturity survey on

KBM (Jääskeläinen et al. 2022).

Since the intervals between the Likert scale values

are not equal (Cohen et al. 2007), the responses were

grouped to two categories: agree and disagree. The

distribution of responses between these two

categories was calculated as a percentage while

leaving out the neutral responses. The responses

agreeing with the development of each KBM section

were based on five to ten statements each, and the

percentages representing the satisfied were based on

a single statement. When responses are distributed

equally between satisfied and dissatisfied, or

agreement and disagreement, the responses are

interpreted as dissatisfied and disagreement, as there

is a significant amount of respondents not satisfied

with the practices or thinking the practices are not

developed.

The results are analyzed using a framework

suggested for this maturity survey by Jääskeläinen et

al. (2022). The framework is a matrix with four

categories: novice, facilitator, experimenter, and

advanced exploiter (see figure 2). Jääskeläinen et al.

(2022) present the novice as having the practices in a

rather primitive level and suggest that these practices

should be prioritized in development. Facilitator

describes those practices that may not be very

developed but meet the needs of the organization.

Practices that fall into the experimenter area are

developed and even novel, but not implemented fully.

Advanced exploiter is described as the desired

situation: the practices are advanced and exploited. In

section 5, each section of KBM will be placed on this

framework separately for customer organizations,

and for project companies.

4 RESULTS

The results are presented in three tables. Table 1

presents the percentage of responses in agreement

with the development of the KBM. Table 2 presents

the percentages of respondents who were satisfied

with each section of KBM. Table 3 gathers the open

answers.

Table 1: The percentage of responses in agreement with the development of the KBM practices.

Sections of KBM

Customer or

g

anizations Pro

j

ect com

p

anies

A. Vision an

d

strate

gy

of an or

g

anization

66% 88%

B. Governance and or

g

anization of a

p

ro

j

ect

47% 61%

C. Information needs in a

p

ro

j

ect

57% 78%

D. Information ac

q

uisition in a

p

ro

j

ect

71% 70%

E. Information or

g

anization and stora

g

e in a

p

ro

j

ect 52% 62%

F. Information

p

roducts in a

p

ro

j

ect

45% 61%

G. Information and knowled

g

e sharin

g

in a

p

ro

j

ect 59% 69%

H. Information usa

g

e in a

p

ro

j

ect 62% 86%

State of Knowledge-based Management in Project Networks: Case in Finnish Infrastructure Construction Sector

129

Table 2: The percentage of respondents who were satisfied with the KBM practices.

Challenges Customer organizations Project companies

Difficulty of implementing practices 9 1

Insufficient skills 4 4

Insufficient resources 3 1

Lack of common practices 11 4

Undefined responsibilities 2 6

Inadequate information systems and interfaces 3 1

Inadequate information management processes 5 13

Inadequate information products 2 0

Undefined information needs (of one’s own organization) 7 1

Undefined information needs (of other organizations) 2 5

Sharing implicit knowledge 1 2

Table 3: Challenges mentioned in open-ended questions.

Sections of KBM Customer organizations Project companies

A. Vision and strategy of an organization 52% 59%

B. Governance and organization of a project 21% 50%

C. Information needs in a project 36% 62%

D. Information acquisition in a project 36% 65%

E. Information organization and storage in a project 38% 54%

F. Information products in a project 33% 73%

G. Information and knowledge sharing in a project 44% 64%

H. Information usage in a project 54% 65%

As shown in table 1, the respondents in customer

organizations are mostly agreeing with the

development of the practices in KBM. However, they

are clearly agreeing only on the development of the

practices in information acquisition. The sections of

governance and organization of projects and the

creation and usage of information products seem to

have undeveloped practices.

The project companies’ respondents are

significantly agreeing with the development of the

practices in most of the sections. The lowest

development of the practices seems to be in

governance and organization of projects, information

storage, and the usage of information products.

However, even these sections have more than 60% of

the respondents thinking the practices are developed.

Whereas the respondents in customer organizations

had more than 60% agreeing with the practice

development in only three sections.

Table 2 shows that customer organizations’

respondents were only satisfied with the practices

regarding organizational strategy, and information

usage. And even with these sections, the percentage

of satisfied respondents is only slightly more than

50%. The least satisfied they are with the practices in

governance and organization of projects.

Respondents in project companies are clearly

more satisfied with the KBM practices than their

counterparts in the customer organizations. They are

quite significantly satisfied with the usage of

information products, and slightly dissatisfied with

governance and organization of projects. With the

other sections, they are satisfied.

A significant number of respondents from

customer organizations reported challenges with

implementation, and a lack of common practices.

Multiple respondents mentioned that there is a lot of

development done in strategic level, but the practices

do not change in operational level. However, reasons

for this difficulty were not reported and therefore it is

not possible to state if this results from resistance to

change, insufficient efforts to implement the

practices, or other reasons. Lack of common practices

includes working in siloes, which results in time-

consuming information acquisition. In addition,

respondents mentioned not having rights to all

information they need, which increases the

fragmentation of work in the network. Lack of

common practices makes it also more difficult to

share information, as reported by the respondents.

Undefined information needs of the customer

organization were reported by the respondents from

both categories of organizations. It seems that the

undefined information needs of customer

organization creates challenges to gathering

information in both kinds of organizations.

Interestingly, same challenge in project companies

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

130

was not reported as many times by respondents in

either one of the categories of organizations.

Some respondents from project companies

mentioned that customer organizations do not

understand their information needs. This challenge

was not identified by customer organizations as it was

not mentioned even once. One respondent stated that

as customer organization has not identified their own

information needs, it is difficult to define roles and

responsibilities in the project company side too.

Another responder claimed it's the other way around:

if the roles and responsibilities are not clear, the

information needs cannot be clearly defined either.

Thus, the unidentified information needs, and unclear

roles and responsibilities seem to be connected, even

if the cause-and-effect relationship is unclear.

Respondents from project companies stressed the

central role of the customer organization in multiple

other responses too, including the mentions of

inadequate information management processes.

Information gets disorganized and stored in multiple

different locations, which results in information

getting outdated and disappeared. The respondents

from project companies highlight how the

information acquisition is even more difficult when

it’s managed by customer organization. Respondents

from the customers’ side did not stress the role of

other organizations in information management.

Another difference between customer organizations,

and project companies, is that the latter reported

insufficient skills mainly related to information

products whereas the first reported insufficient skills

relating to KBM.

5 DISCUSSION

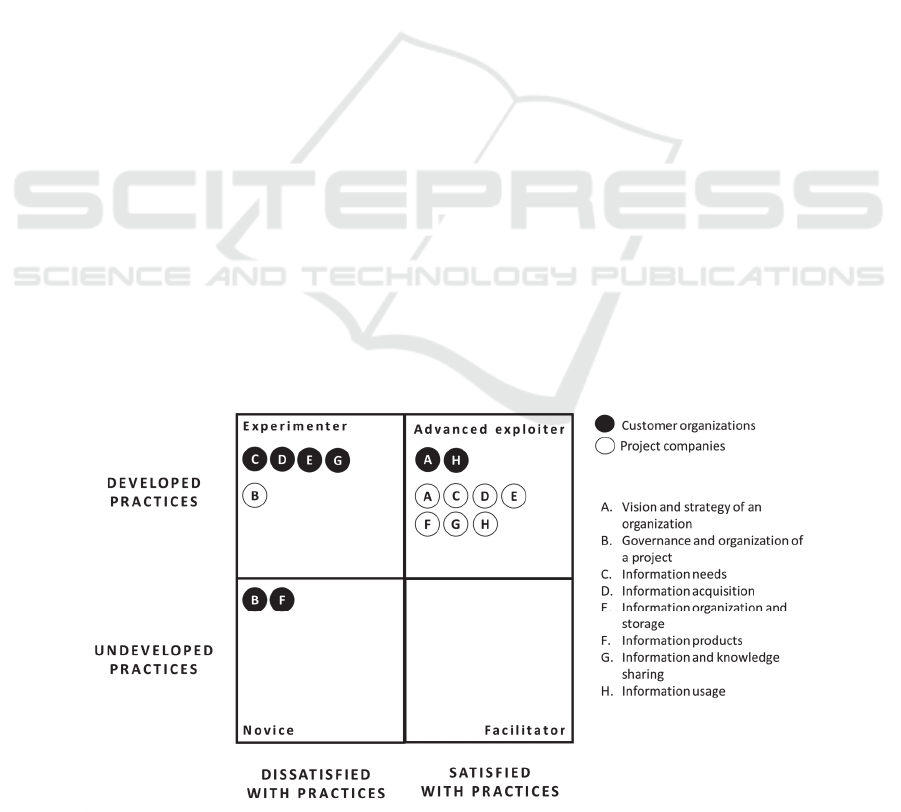

The results are visually presented in figure 3. This

figure shows how the KBM practices are less

developed in customer organizations than in project

companies. The most striking is the difference of

satisfaction with these practices: respondents from

customer organizations are mostly dissatisfied with

KBM practices whereas other respondents are mostly

satisfied. Jääskeläinen et al. (2022) state that the

organizations with high employee satisfaction to

KBM practices have in common that they link their

KBM better to strategy (A) and have better structures

supporting KBM (B), more advanced information

products (F), and better systems and processes for

storing information (E). This seems to apply for

project companies too.

As presented in figure 3, customer organizations

can be interpreted as experimenters with novice

tendencies. According to Jääskeläinen et al. (2022),

for experimenter and novice organizations it is

essential to focus on aligning their KBM practices

with their strategy i.e., implementing the practices that

have been developed in a strategic level. The difficulty

of implementing practices was also mentioned by

multiple respondents in the open answers. The

misalignment of KBM and business strategies, and

technology are known barriers for knowledge sharing

(Riege 2005; Wang and Wang 2009). The whole

project network would benefit if customer

organizations would also focus on identifying their

information needs (C) as it was reported as insufficient

by both categories of organizations. Diversified and

systematic fulfilment of information needs facilitates

decision-making (Hellsten and Myllärniemi 2019) and

helps organization-wide knowledge management.

Figure 3: KBM in customer organizations and project companies.

State of Knowledge-based Management in Project Networks: Case in Finnish Infrastructure Construction Sector

131

Project companies can be interpreted as advanced

exploiters with experimenter-level project

governance and organization (B). Advanced

exploiters have advanced KBM practices and can

exploit them fully (Jääskeläinen et al. 2022). Project

companies should focus on better governance and

organization of projects (B), including allocating

more resources to KBM and especially having more

defined roles and responsibilities. However, the open

answers highlighted how difficult it is to improve

these practices without cooperation with customer

organization. It seems that for project companies the

priority is to define common practices and processes

with customer organizations to enable better

information and knowledge sharing and acquisition.

KBM in project networks is cooperation, i.e.,

organizations need to align their internal activities

(Bruswicker and Vanhaverbeke 2015) and

communicate actively in the network (Vuori et al.

2019), in order to achieve fluent knowledge sharing

and acquisition. Especially the respondents from

project companies highlighted the importance of the

cooperation with customer organization in their open

answers. To make the change, organization and

governance in common projects need to develop

further: the importance of information and knowledge

sharing needs to be made clear for everyone, and time

and resources must be allocated sufficiently (Riege

2005). The respondents from both categories of

organizations reported that the information

management would be of better quality if there was

enough time to do it properly. The misalignment of

IT-systems is also noted by the respondents and

authors such as Vuori et al. (2019) and Riege (2005).

6 CONCLUSIONS

As reported in this research and by others (e.g.

Bhargav and Koskela 2009; Lancini 2015; Bojica et

al. 2018; Agostini et al. 2020) the interorganizational

cooperation is key for successful KBM in project

networks. Organizations cannot operate alone, and

internal knowledge gaps need to be increasingly filled

by cooperating with external partners (Bojica et al.

2018). This research has also shown that customer

organizations have a key role in developing KBM

further in project network. If they manage to fully

exploit their KBM practices, they can improve KBM

in project companies too in their common projects

Project companies should invest especially on

communication and cooperation with customer

organizations. By frequently communicating with the

customer organization, they can be more aware of the

customers’ information needs. Since project

companies have more developed practices, they could

take a more proactive role in information

management in their common projects.

This research provided more insight on KBM in

project network. According to Agostini et al. (2020)

research on interorganizational KM or KBM in

project networks is quite narrow, by focusing on

specific types of interorganizational relationships,

knowledge transfer among organizations and on

knowledge protection. This research took a quite

wide perspective on KBM and we had a specific type

of project network in which customer organization

has a key role, which doesn’t seem to be a much-

studied network in this field. We were able to

discover how important the customer organization’s

role is in a poject network.

The practical community can derive ideas for

developing KBM in their project network, whether

they represent a customer organization or a project

company. This research is also part of a research

programme ProDigial, which aims for further

digitalization initiatives and increased productivity in

Finnish infrastructure construction sector. Our

practical contribution from this research programme

is a guide for customer organizations to develop

KBM in their project networks.

REFERENCES

Agostini. L., Nosella, A., Sarala, R., Spender, J.-C.,

Webner, D. (2020) Tracing the ecolution of the

literature on knowledge management in inter-

organizational contexts: a bibliometric analysis. Journal

of Knowledge Management. Vol 24(2). pp. 463-490.

Ajmal, M. M., Helo, P., Kekäle T. (2010) Critical factors

for knowledge management in project business. Journal

of Knowledge Management. Vol. 14(1). pp. 156-168.

Alin, P., Maunula, A. O., Taylor, J. W., Smeds, R. (2013)

Aligning misaligned systemic innovations: Probing

inter-firm effects development in project networks.

Bakker, R. M. (2011) ”It’s only temporary”: Time and

learning in interorganizational projects. University

Tilberg. Tilberg.

Bhargav, D., Koskela, L. (2009) Collaborative knowledge

management – A construction case study. Automation

in Construction. Vol. 18. pp. 894-902.

Bojica, A. M., Estrada, I., del Mar Fuentes-Fuentes, M.

(2018) In good company: when small and medium-

sized enterprises acquire multiplex knowledge from

key commercial partners. Journal of Small Business

Management. Vol. 56(2). pp. 294-311.

Brunswicker, S., Vanhaverbeke, W. (2015) Open

innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises

(SMEs): external knowledge sourcing strategies and

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

132

internal organizational facilitators. Journal of Small

Business Management. Vol. 53(4). pp. 1241-1263.

Buckley, P. J., Glaister, K. W., Klijin, E., Tan, H. (2009)

Knowledge accession and knowledge acquisition in

strategic alliances: the impact of supplementary and

complementary dimensions. British Journal of

Management. Vol. 20(4). pp. 598-609.

Choo, C.W. (1998) The Knowing Organization: How

Organizations Use Information to Construct Meaning,

Create Knowledge, and Make Decisions. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Choo, C.W. (2002) Information management for the

intelligent organization: the art of scanning the

environment. Information Today, Inc.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., Morrison K. (2007) Research

methods in education. 6th ed. London: Routledge.

Grant, R. M. (1996) Toward a knowledge-based theory of

the firm. Strategic Management Journal. Vol. 17. pp.

109-122.

Gunasekaran, A. (2005). Benchmarking in public sector

organizations. Benchmarking: An international Journal.

Emerald Group.

Hellsten, P. and Myllärniemi, J. (2019) Business

intelligence process model revisited. KMIS 2019. pp.

341-348.

Hellsten, P., Paunu, A., Väyrynen, H. (2021) Notions on

Knowledge from Networks – Benchmarking in Public

Sector. KMIS 2021.

Hellsten, P. and Pekkoja, S. (2019) The impact levels of

digitalization initiatives. EGOV 2019.

Inkinen, H. (2016) Review of empirical research on

knowledge management practices and firm

performance. Journal of Knowledge Management Vol.

20. pp. 230–257.

Jalonen, H. (2015) Tiedolla johtamisen näyttämö ja kulissit.

Tiedolla johtaminen hallinnossa. Teoriaa ja käytäntöjä.

Jääskeläinen, A., Sillanpää, V., Helander, N., Leskelä, R.

L., Haavisto, I., Laasonen, V., & Torkki, P. (2022)

Designing a maturity model for analyzing information

and knowledge management in the public sector. VINE

Journal of Information and Knowledge Management

Systems.

Isaksson, A. J., Harjunkoski, I., & Sand, G. (2018) The

impact of digitalization on the future of control and

operations. Computers & Chemical Engineering. Vol.

114. pp. 122-129.

Kaivo-oja, J., Virtanen, P., Jalonen, H. and Stenvall, J.

(2015) “The effects of Internet of Things and Big Data

to organizations and their knowledge management

practices”, Knowledge Management in Organizations –

Lecture Note in Business Information Processing, Vol.

224. pp. 495–513.

Kasper, E. (2015). A Definition for Infrastructure -

Characteristics and Their Impact on Firms Active in

Infrastructure. Technische Universität München,

School of Management. Dissertation.

Lancini, A. (2015) Evaluating Interorganizational

Knowledge Management: The Concept of IKM

Orientation. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge

Management. Vol. 13(2). pp. 117-129.

Larsson, J., Eriksson, P.-E., Olofsson, T., Simonsson, P.

(2013) Industrialized construction in the Swedish

infrastructure sector: core elements and barriers.

Construction Management and Economics. Vol. 32(1-

2).

Lindgren, I., Østergaard Madsen, C., Hofmann, S., Melin,

U. (2019) Close encounters of the digital kind: A

research agenda for the digitalization of public services.

Government Information Quarterly. Vol 36(3). pp. 427-

436

Lundin, R. A., Söderholm, A. (1995) A theory of the

temporary organization. Scandinavian Journal of

Management. Vol. 11(4). pp. 437-455.

Moss, T. (1999) “Management forecast: optimizing the use

of organizational and individual knowledge”, Journal of

Nursing Administration. Vol. 29(1). pp. 57-62.

Myllärniemi, J., Helander, N., Pekkola, S. (2019)

Challenges in Developing Data-based Value Creation.

KMIS 2019. pp. 370–376.

Nonaka, I. (1994) A dynamic theory of organizational

knowledge creation. Organization Science. Vol. 5(1).

pp. 14-37.

Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H. (1995) The knowledge-creating

company: How Japanese companies create the

dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press.

Oxford.

Obstfeld, D. (2012) Creative projects: a less routine

approach toward getting new things done. Organization

Science. Vol. 23(6). pp. 1571-1592.

Omotayo, F. O. (2015) Knowledge management as an

important tool in organisational management: a review

of literature. Library philosophy and practice. Lincoln:

University of Idaho Library.

Parviainen, P., Tihinen, M., Kääriäinen, J., & Teppola, S.

(2017) Tackling the digitalization challenge: how to

benefit from digitalization in practice. International

journal of information systems and project

management. Vol. 5(1). pp. 63-77.

Riege, A. (2005) Three-dozen knowledge-sharing barriers

managers must consider. Journal of Knowledge

Management. Vol. 9(3). pp. 18-35.

Spender, J. C., Grant, R. M. (1996) Knowledge and the

firm: overview. Strategic Management Journal. Vol.

17. pp. 5-9.

Thierauf, R.J. (2001) Effective Business Intelligence

Systems. Quorum Books. Westport (CT).

Vuori, V., Helander, N., Mäenpää, S. (2019) Network level

knowledge sharing: Leveraging Riege’s model of

knowledge barriers. Knowledge Management Research

and Practice.

Wang, S., Wang, H. (2009) An induction model of

information technology enabled knowledge-

management: A case study. Journal of Information

Technology Management. Vol. 20(1). pp. 1-14.

Wiig, K.M. (1997) “Knowledge management: an

introduction and perspective”. The Journal of

Knowledge Management, Vol. 1(1). pp. 6-14.

State of Knowledge-based Management in Project Networks: Case in Finnish Infrastructure Construction Sector

133