Identifying User Experience Aspects for Voice User Interfaces with

Intensive Users

Kristina K

¨

olln

1 a

, Jana Deutschl

¨

ander

2 b

, Andreas M. Klein

3 c

, Maria Rauschenberger

1 d

and

Dominique Winter

4 e

1

Faculty of Technology, University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer, Emden, Germany

2

Berliner Hochschule f

¨

ur Technik, Berlin, Germany

3

Department of Computer Languages and Systems, University of Seville, Seville, Spain

4

University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany

Keywords:

Voice User Interface, VUI, User Experience, UX, Voice Assistant, HCI, User-centered.

Abstract:

Voice User Interfaces (VUIs) are becoming increasingly available while users raise, e.g., concerns about pri-

vacy issues. User Experience (UX) helps in the design and evaluation of VUIs with focus on the user. Knowl-

edge of the relevant UX aspects for VUIs is needed to understand the user’s point of view when developing

such systems. Known UX aspects are derived, e.g., from graphical user interfaces or expert-driven research.

The user’s opinion on UX aspects for VUIs, however, has thus far been missing. Hence, we conducted a

qualitative and quantitative user study to determine which aspects users take into account when evaluating

VUIs. We generated a list of 32 UX aspects that intensive users consider for VUIs. These overlap with, but

are not limited to, aspects from established literature. For example, while Efficiency and Effectivity are already

well known, Simplicity and Politeness are inherent to known VUI UX aspects but are not necessarily focused.

Furthermore, Independency and Context-sensitivity are some new UX aspects for VUIs.

1 INTRODUCTION

A Voice User Interface (VUI) is any kind of software

and device combination controlled by user’s spoken

input. VUIs have become increasingly popular

in recent years, and their use is predicted to rise

even more in the future (Strategy Analytics, 2021).

However, although a lot of people own a VUI (e.g., in

their smartphone), they do not necessarily use them.

Possible reasons for non-use are diverse, e.g, fear of

data misuse and monitoring. Yet, on the other end

of the spectrum is a group of intensive users (Klein

et al., 2021). These intensive users show an appreci-

ation for the use of VUIs that goes beyond the pure

functionality, i.e., user experience aspects of VUIs.

To develop a positive User Experience (UX), the

Human-Centered Design (HCD) Framework has be-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8625-4903

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3851-4384

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3161-1202

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5722-576X

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2697-7437

come widely accepted. HCD is a holistic approach for

designing a UX that fits the target group by focusing

on the user (ISO 9241-210, 2019). We should know

which UX aspects users take into account when eval-

uating the quality of VUIs, since different UX aspects

are important for different users or products (Meiners

et al., 2021). For example, some users are concerned

about which data is collected and how, while others

mention the need for higher accuracy of commands

(Rauschenberger, 2021; Klein et al., 2021).

Recent research includes several attempts to de-

fine important UX aspects of VUI using an expert-

driven process (Hone and Graham, 2000; Kocaballi

et al., 2019; Klein et al., 2020a). To the best of our

knowledge, however, there is no user-driven identifi-

cation of relevant UX aspects for VUIs that is based

on up-to-date user data.

In this article, we present the identified UX as-

pects using a user-centered mixed-methods approach

(McKim, 2017; ISO 9241-210, 2019). We chose to

concentrate on intensive users because they engage

with VUIs in depth and can offer profound insights

Kölln, K., Deutschländer, J., Klein, A., Rauschenberger, M. and Winter, D.

Identifying User Experience Aspects for Voice User Interfaces with Intensive Users.

DOI: 10.5220/0011383300003318

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2022), pages 385-393

ISBN: 978-989-758-613-2; ISSN: 2184-3252

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

385

into extensive usage scenarios.

This article is structured as follows: Section 2 in-

troduces UX, recent research about UX of VUIs, and

mixed methods. Section 3 explains our methodology

by describing the interview and survey process, the

participants, and the qualitative content analysis. Sec-

tion 4 presents and discusses our results. Section 5

finishes with a conclusion and future work.

2 BACKGROUND & RELATED

WORK

Current challenges when using VUIs are, e.g., speech

intelligibility, correct command execution, data secu-

rity, and privacy (Klein et al., 2021; Tas et al., 2019;

Rauschenberger, 2021). UX assessment by consider-

ing specific UX aspects for VUIs is an essential evalu-

ation method for overcoming barriers and skepticism

as well as meeting users’ needs. In the following, we

briefly introduce UX, how to identify UX aspects for

VUIs, and VUI assessment approaches and methods.

UX is a holistic concept that considers emotion,

cognition, and physical action before, during, and af-

ter using a product (ISO 9241-210, 2019). UX has

a set of distinct quality criteria: pragmatic, i.e., clas-

sical usability criteria such as efficiency, and hedo-

nic, i.e., non-goal criteria such as stimulation (Preece

et al., 2002). These UX quality criteria, also called

UX aspects, can be identified and evaluated, e.g.,

by conducting empirical studies. Focusing on rel-

evant UX aspects enables efficient product develop-

ment and evaluation, e.g., by using the most suitable

questionnaires (Winter et al., 2017).

Still, there is no consensus on UX measurement

specifically for VUIs (Seaborn and Urakami, 2021).

Various methods are available for VUI evaluation,

but they do not necessarily focus on UX. A study

analyzed six questionnaires that are commonly ap-

plied for VUI evaluation and assessed their suitability

regarding various UX dimensions (Kocaballi et al.,

2019). Its authors recommend either combining

questionnaires to cover UX more comprehensively

or measuring a distinct UX dimension in detail.

Another VUI evaluation method is the application

of heuristics, which are guidelines for design and

evaluation. They mostly focus on usability and

overlook certain UX aspects (Wei and Landay, 2018;

Langevin et al., 2021).

Another option to measure different UX aspects

for VUIs is the modular questionnaire concept UEQ+

(Schrepp and Thomaschewski, 2019b). Because

of the flexible approach, researchers could, for

example, utilize three voice quality scales mixed

with, say, 3 out of 17 other UEQ+ scales. Thereby,

the researchers create a questionnaire related to

their research question for product-specific UX

aspect evaluation (Klein et al., 2020b). Examples of

other UEQ+ scales are Attractiveness, Novelty, and

Efficiency. The voice quality scales are constructed

with consideration of human-computer interaction

(HCI) and the VUI design process (Klein et al.,

2020a). User, system, and context all influence HCI

significantly (Hassenzahl and Tractinsky, 2006).

Improving the VUI design process requires a deep

understanding of context, user, and application to

define relevant evaluation criteria (Cohen et al.,

2004) but the definition back then was only targeting

usability instead of the holistic UX concept.

In recent studies, mixed-methods approaches have

become more popular (McKim, 2017), as they pro-

vide certain advantages. For example, mixed meth-

ods can be applied in single questionnaire experi-

ments if there is a questionnaire with a combination

of standardized and open questions (Biermann et al.,

2019). Another example is comprehensive study de-

sign (Iniesto et al., 2021), where the combination of

standardized questionnaires and semi-structured in-

terviews allows the researchers to cover broader as-

pects and gain in-depth information at the same time.

Our mixed-methods approach aims to identify the

missing UX aspects that users take into account when

evaluating VUIs.

3 METHODOLOGY

Our target group comprises intensive VUI users who

use VUIs regularly, i.e., from daily to several times a

week, in a private or professional environment (Klein

et al., 2021). They have at least one year of usage ex-

perience and use VUIs in various scenarios. Hence,

intensive users have already dealt with VUIs more

deeply and can provide comprehensive insights into

their use. We aim to identify the target group’s UX

aspects when using VUIs. For this purpose, we for-

mulated the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: What is intensive users’ VUI frequency of use?

RQ2: What are intensive users’ reasons for VUI use?

RQ3: What are intensive users’ UX aspects for VUI?

First, we explore the frequency of use (RQ1) of in-

tensive users by considering shorter time intervals, as

in previous literature. Next, we ask users about their

reasons for use (RQ2) to reveal the intensive users’

usage patterns and scenarios. We then asked the in-

tensive users’ to share their positive and negative VUI

WEBIST 2022 - 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

386

Table 1: Participants’ durations, devices, and applications.

Participants

Duration

of use

Devices Application

P1 3 years Alexa Accessibility (visual), smart home control

P2 >5 years Alexa, Siri Accessibility (visual), librarianship

P3 >10 years Alexa*, Siri Accessibility (visual), smartphone control

P4 3 years Alexa, Siri Accessibility (visual), search queries

P5 >10 years Dragon, Siri Accessibility (visual), working tool, smartphone control

P6 >10 years Alexa, Dragon, Siri Accessibility (motor), working tool, smartphone control

P7 >5 years Alexa, Siri VUI development

P8 >5 years Alexa, in-car entertainment Smart home control

P9 1 year Google Assistant Timer, search queries

P10 >5 years Alexa, smartphone** Radio substitute, (fun) search queries

(*stopped using Alexa, **unknown smartphone brand)

experiences as well as suggestions for VUI improve-

ments in order to determine noteworthy UX aspects

for the target group (RQ3).

To answer the RQs, we follow a mixed-methods

approach: we conduct a qualitative study with semi-

structured interviews followed by a quantitative study

with an online questionnaire. The questionnaire is de-

signed to verify the results of the interviews and to

compare them with a broader sample of participants.

3.1 Qualitative User Study with

Interviews

We conducted ten semi-structured interviews with a

heterogeneous group of intensive users in the qualita-

tive study. We then analyzed the collected data with a

qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 1994).

3.1.1 Procedure

From April to May 2021, we conducted ten inter-

views applying the semi-structured expert-interview

methodology (Bogner et al., 2014). In order to answer

our three RQs, we constructed the interview guide-

lines to consist of questions about the participants’

positive and negative expectations and experiences re-

garding VUIs as well as their contexts of use.

We run two pretests to ensure that the guidelines

were useful and guiding. Afterwards, we translated

the interview guidelines into English to include inter-

national participants and made an additional version

to interview a user whose children also use the VUI.

The interview guidelines are available in the original

language German and English translation in the re-

search protocol (K

¨

olln et al., 2022).

We conducted the interviews during online video

sessions using Microsoft Teams, or, in one case, a

phone call. The interviews were recorded and subse-

quently transcribed with a simple scientific transcript

(Dresing and Pehl, 2018) and made anonymous. Two

interviews had to be documented with a memory log

because the recording failed. All transcriptions and

memory logs are available in the research protocol

in their original language (K

¨

olln et al., 2022). Af-

terwards, the collected data was analyzed with the

qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 1994).

3.1.2 Interview Participants

All interview participants (see Table 1) meet our re-

quirements for our target group, which are: they all

use VUIs daily in a private or professional context

and have at least one year of usage experience (see

Table 1 column Duration of use). We included P7,

who works with VUIs daily in VUI software develop-

ment, but does not actually consider themself a reg-

ular user. P7 responded to a social media call on the

platform LinkedIn. Other participants, who were al-

ready known to use VUIs more intensively, were ac-

quired from the personal networks of the authors.

The interviewees are heterogeneous, e.g., in their

contexts of use and characteristics. Four out of ten

use VUIs in a professional environment, and the

other six in private environments. Six out of ten

participants have an impairment, while the other four

have none. The participants are 27 to 69 years old.

P10 also uses the VUI with their children, who are

four and six years old. Two participants are female,

eight are male. Most participants use Alexa (8/10),

followed by Siri (6/10). The speech recognition soft-

ware Dragon is used as a working tool (2/10). Least

used are an in-car entertainment system, Google

Assistant, and an unspecified smartphone VUI (each

1/10) (see Table 1 column Devices).

The main usage scenarios of the participants are:

making their daily lives easier as users with impair-

ments (6/10), smartphone control and search queries

(each 3/10), and smart home control (2/10). In addi-

tion, there are some specific main applications, such

as librarianship, timer, radio substitute, or VUI devel-

opment (each 1/10) (see Table 1 column Application).

Identifying User Experience Aspects for Voice User Interfaces with Intensive Users

387

3.1.3 Qualitative Content Analysis

We applied the summarizing content analysis, one

form of the quality content analysis that is well-

known and most often used in German-speaking

countries (Mayring, 1994).

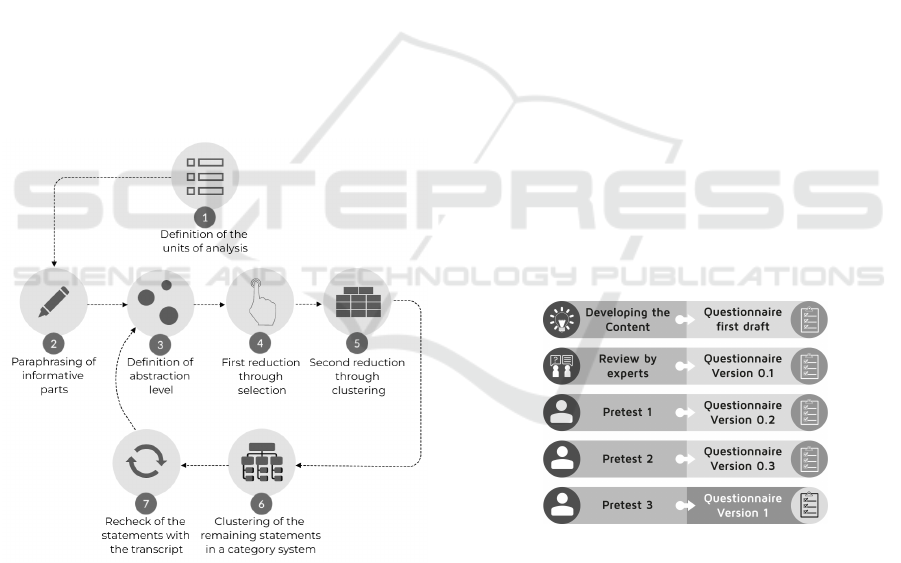

In the summarizing content analysis process (see

Fig. 1), we analyzed the transcripts using a tech-

nique called “coding”: first, we defined the transcripts

as the units of analysis. We then highlighted the

information-bearing parts and summarized their key

message on an abstraction level that fit our purpose.

These key messages are now called “codes.” We then

removed all selections that were not related to our re-

search questions to make a first reduction, followed

by clustering codes with similar key messages. The

remaining codes were then clustered into a category

system that is the basis for our list of UX aspects. We

finally rechecked all interviews with the developed

code system in a second round of coding to ensure all

interviews were coded with the same procedure. Be-

cause only minor changes were made to the code sys-

tem in the second round, an additional control round

was unnecessary.

Figure 1: Process of conducting a summarizing content

analysis based on (Mayring, 1994).

Following this method, two authors alternately

coded using the software tool MAXQDA Standard

2000 (Release 20.4.1) in the following way: author

A codes P1, then author B codes P2, and so on un-

til P10 is reached. In the second round, the authors

changed the participants’ transcriptions, so author A

coded P2, then author B coded P1, and so on.

3.2 Quantitative User Study with a

Survey

We conducted an online survey with intensive users to

obtain more comprehensive results. We obtained an

additional amount of qualitative data from the ques-

tionnaires, which was also analyzed with an adjusted

qualitative content analysis.

3.2.1 Procedure

We conducted a survey with German-, English- and

Spanish-speaking participants using Google Forms

from April to June 2021.

We developed our questionnaire as follows (see

Fig. 2): first, we developed the content based on

the research questions and the findings of the inter-

views. The questionnaire combines quantitative and

qualitative questions. In our first pilot test, we pre-

sented our survey draft to four UX experts. We made

changes, e.g., to the informative texts or order of ques-

tions. Then we did three pretests consecutively, each

with the reworked version from the preceding pretest.

After each pretest, we mostly just made changes in

the wordings in order to help the participants to bet-

ter understand the questions. Our final questionnaire

contains 19 questions about the experiences and ex-

pectations of the VUI users regarding the VUIs. The

complete questionnaire can be found in the research

protocol in English, German, and Spanish versions

(K

¨

olln et al., 2022).

Figure 2: The development process of the questionnaire.

The survey was then shared on the social media

platforms LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter as well

as through the personal networks of the authors.

Contacts then also shared the survey with their

contacts and on their social media channels. We

repeated the call to participate a few times to gain

additional participants.

For the qualitative content analysis, we partly ad-

justed the summarizing content analysis to our re-

search needs: we did not build a new code system but

used the code system that we had developed for the

WEBIST 2022 - 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

388

interviews. Hence, we were able to match the results

of the survey with our findings from the interviews.

3.2.2 Survey Participants

We collected 76 participant responses and excluded

24 due to the following reasons: one duplicate, five

records had fewer than three questions answered,

and 18 participants did not meet the target group

requirements of a high frequency of use. For the

analysis, we took 52 participants into account. We

found that 69% (36/52) of the survey participants

were male, 29% (15/52) were female, and 2% (1/52)

did not answer the question. The average age of the

survey participants is 43 (SD 13). The participants

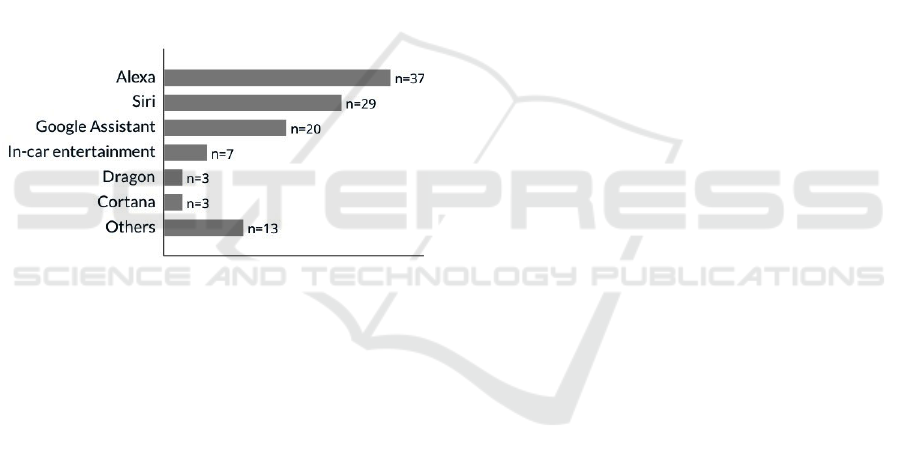

use diverse software and devices (see Fig. 3). Of all

named devices, Alexa is the most commonly used

(37/52), followed by Siri (29/52). The third most used

device of the participants is Google Assistant (20/52).

This keyword combines all mentions of Google

Figure 3: Devices used by the target group (N = 52).

VUIs because the participants were not always clear

about which Google device they used (some wrote

“Google,” “Google Voice,” or even “Google Home,

or Google Assistant?”). Voice-controlled navigation

or entertainment systems of cars, disregarding the

manufacturer of the car, were summarized as in-car

entertainment (7/52). Least frequently named were

the speech recognition software Dragon (3/52) as

well as Cortana (3/52), followed by a few other VUIs

that were each named by max. 2 participants (13/52).

While we identified Alexa and Siri as the most

commonly used VUIs among our participants, a

representative German study (N = 3184) found that

Google Assistant (12%) and Alexa (9%) are the

most commonly used (Tas et al., 2019). This may

differ from our participants, but since we did not

look for brand-specific evaluations, we do not expect

significant discrepancies in our results.

4 RESULTS & DISCUSSION

We processed our collected data according to the

description in the previous sections with the con-

tent analysis (Mayring, 1994). Hence, the quali-

tative data from both studies were analyzed using

the data analysis software MaxQDA Standard 2020

(Release 20.4.1) both with the operating system Mi-

crosoft Windows 10. Quantitative data were analyzed

in Microsoft Excel (Version 2204).

We consider 62 participants for the qualitative and

quantitative study, 71% male (n = 44), 27% female

(n = 17), and 2% (n = 1) who did not answer. Al-

though our study is not representative, its distribution

is in line with current literature (77% (Pyae and Joels-

son, 2018), 72% (Sciuto et al., 2018), and 79% (Klein

et al., 2021) male participants). As in other studies,

our distribution of gender among our participants is

biased towards male users for VUIs.

We first report our interview results (n = 10) and

then the survey results (n = 52) in each section. Quo-

tations are translated from the original language Ger-

man, English, or Spanish, and the original quotes are

available in the research protocol (K

¨

olln et al., 2022).

4.1 What Is Intensive Users’ VUI

Frequency of Use?

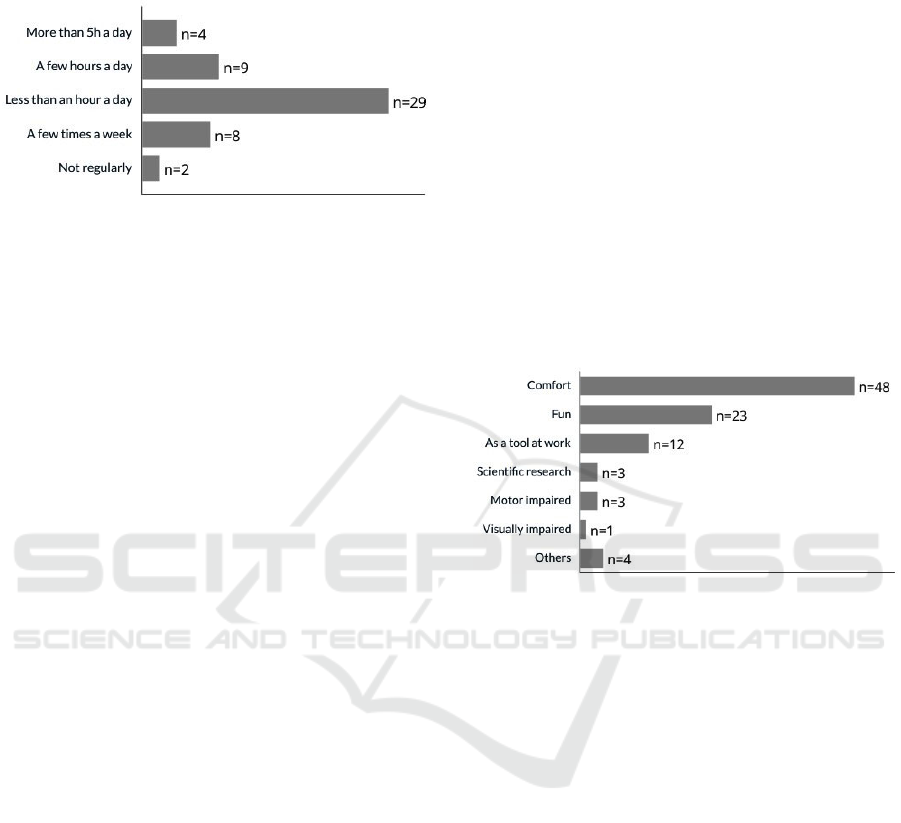

Even though all interview participants (n = 10) meet

our definition for intensive users, considerable differ-

ences in the scope of the frequency of use were re-

ported by the participants. Therefore, we asked the

survey participants (n = 52) to be more specific about

their frequency of use. That is why we have subdi-

vided the answer options for daily use into three op-

tions: less than an hour a day, a few hours a day, and

more than five hours a day. Out of the survey partici-

pants who use their VUI daily, most use it less than an

hour a day (29/52). This is followed by a few hours

a day (9/52) and more than five hours a day (4/52).

Fewer survey participants use their VUI a few times a

week (8/52) and some VUI developers use it not reg-

ularly (2/52) (see Fig. 4).

Another study, which also examined the frequency

of use, found that 76.6% of the identified inten-

sive users used VUI on a daily basis (Klein et al.,

2021), which is in line with our results. However,

the intensive users were only distinguished between

approximately once a day and several times a day.

A population-representative study conducted in Ger-

many in 2019 revealed 11% of daily VUI users and

19% several times a week, resulting in 30% intensive

users (SPLENDID RESEARCH GmbH, 2019).

Our findings are in line with these results and

Identifying User Experience Aspects for Voice User Interfaces with Intensive Users

389

show the survey participants’ distribution for VUI fre-

quency of use in more detail.

Figure 4: Frequency of use of the survey participants (N =

52).

The frequency of use distribution could have its

origin in the different usage scenarios of the VUIs.

One typical usage scenario of Alexa is, e.g., the timer

function. This only takes a few seconds to execute.

However, if a user uses Dragon to dictate their emails,

they sometimes use the device the whole day as a

tool at work or even in their private time. Therefore,

the frequency of use is connected not only to the VUI

system, but also to the context of use. For a more

precise analysis, the context needs to be considered

in the design of VUIs.

4.2 What Are Intensive Users’ Reasons

for VUI Use?

The interview participants named various reasons for

their VUI usage. P2 describes how, as a blind person,

using VUIs gives them the opportunity to do things

for which they have no easy alternative solution. For

example, they uses Alexa to order audiobooks from

the library since the library website does not have an

accessible checkout. Due to motor impairment, P6

uses Dragon as a tool at work to write most of their

email correspondences. P8 uses a VUI out of con-

venience for the navigation system in their car and

to control their smart home. P10 describes how their

children use Alexa for fun.

Since we identified multiple possible reasons for

use, we formed reasons-for-use categories to which

the survey participants could assign themselves (see

Fig. 5). It was possible to select multiple categories

and to give custom answers.

Most of the survey participants use VUIs for com-

fort (48/52). This was followed by fun (23/52) and as

a tool at work (12/52). A few use VUIs because they

do scientific research on VUIs (3/52) or because of

some kind of impairment, e.g., motor (3/52) or visual

(1/52). This is mostly in line with the answers of the

interview participants. Almost all of them mention

various scenarios in which the VUI grants them com-

fort. Participants with impairments, especially men-

tion several positive experiences with their VUIs: P1

explains that not having to stand up from the sofa to

turn the lights on or off is especially comfortable for

them, since they have low vision. P2 says, “Of course,

I don’t need it in my life, but as a blind person, I

can benefit greatly from smartphones and such assis-

tance systems.” Similarly, P3 says that “as a blind

person, typing on an Iphone is just awkward.” Fun

is also mentioned several times by the interview par-

ticipants: the children of P10 mostly use Alexa to ask

fun questions, and P2 likes to tease Alexa with cheeky

questions and listen to her answers. However, we do

have more interview than survey participants that use

VUIs because of some kind of impairment. In ad-

dition, we have no interview participants that do sci-

entific research on VUIs, unlike some of the survey

participants.

Figure 5: Reasons for using VUIs of the target group (N =

52).

Existing literature has investigated the context of

use, but not the motivation for the usage scenarios

(Klein et al., 2021). However, the motivation for use

also has a major influence on what is important to

the users. (Hassenzahl, 2008) calls these the do- and

be-goals of the users. The do-goals describe what the

user wants to do, while the be-goals describe how the

user wants to feel. The results of our study provide

insights into these do- and be-goals of the target

group, e.g., the participants want to use VUIs for

smart home control (do-goal), or to stay comfortably

on the sofa (be-goal).

We have found that users with disabilities perceive

great potential for VUIs to assist them in their daily

lives. Currently, participants explore VUI features

with a focus on comfort and fun. A few interview

participants stated that they would like to use VUIs for

even more practical applications when VUIs or linked

technologies have a more versatile skill set available,

e.g., using VUIs in autonomous drive to give direction

would be ideal for P2.

WEBIST 2022 - 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

390

Table 2: The identified aspects the target group named for evaluating UX of VUIs.

Index Aspect Interpretation of the participants Int.

(N = 10)*

Sur.

(N = 52)*

1 Comprehension The VUI understands the user correctly, even if they do not speak very clearly. 10 37

2 Error-free Both the result and the operation do not give errors, wrong answers or misunderstandings. 6 34

3 Aesthetic The hardware of the VUI is supposed to be minimalistic. Visual feedback about the status

(listening, processing, disabled, etc.) is positively received as long as it is discreet.

3 35

4 Range of functions The VUI has as many functions and application possibilities as possible. 4 29

5 Simplicity The operation is easy to perform and contains as few steps as possible. 8 23

6 Effectivity The user reaches their goal. 9 17

7 Support of the User The VUI helps users to achieve their goals. 3 22

8 Humanity The user has the feeling of talking to a human being. They can conduct a normal dialogue, the

VUI persona responds with humor and empathy, and the voice sounds natural.

4 21

9 Personal fulfillment The VUI allows the user to live out their personality. They can speak in their dialect and do not

have to disguise themselves in order to be better understood.

3 21

10 Context-sensitivity The VUI knows its user, understands the current situation, and can remember the context of

the conversation.

4 20

11 Efficiency The user reaches their goal without detours. 7 17

12 Privacy The VUI should not permanently listen in, interrupt, or even record private conversations. 6 16

13 Data Security If personal information must be provided, it can be trusted that it will not be shared and will be

handled ethically.

7 15

14 Time-saving The user does not need to fetch a device or press a button and can immediately start the usage

process. They receives the results immediately after the request.

6 14

15 Politeness The VUI does not insult the user; it allows them to finish their sentences and does not activate

without being asked.

0 19

16 Linking with third-

party products

Many third-party products should be compatible. The VUI can easily be connected with them,

and there are no errors in communication.

8 11

17 Safety The VUI gives the user physical and privacy security. For example, security is given by

enabling operation in the car without removing the hands from the steering wheel, or by

protecting the data from external access.

2 16

18 Capability to learn The VUI can learn new commands, learn the personality of its user, and exercise appropriate

reactions. Incorrectly learned commands can be deleted.

2 15

19 Intuitiveness The user does not need to learn a complicated vocabulary, but can immediately communicate

with the VUI using their everyday language. Setting up and learning how to use the VUI is

possible without additional help.

5 12

20 Practicality The VUI helps the user with everyday challenges. 7 10

21 Reliability The VUI responds only when it is addressed, without false activation. The results are correct

and verified. The quality of the interaction should be consistently high.

0 15

22 Help with errors If an error occurs, a way to fix it is shown. There is a help function. 3 11

23 Convenience The user can use the VUI from any situation without having to make an effort. For example,

they can use it from the sofa, bed or desk.

7 7

24 Fun The VUI is fun to use and its humor is appropriate. 3 8

25 Customizability The persona of the VUI can be set by the user according to their preferences (gender,

language, humor, voice, etc.).

0 8

26 Flexibility The VUI can adapt to different users and situations. 4 4

27 Voice The voice of the VUI is pleasant and clearly understandable. 0 7

28 Responsiveness The VUI responds as soon as it is addressed, but only when it is addressed. 0 6

29 Independency The user does not need any assistance in using the VUI. It allows additional independence for

users who would have problems operating a GUI (for example, those with visual or motor

impairment, dyslexics, and children).

4 2

30 Innovation The VUI has new, modern and unique features. 2 1

31 Ad-Free Advertising is not played or can be turned off. 0 2

32 Longevity The VUI can be used for a long time, does not break quickly, and does not need to be

repeatedly replaced with the latest model.

0 2

The aspects are sorted by the total number of mentions. *Mentioned by participants from either the interviews or surveys.

4.3 What Are Intensive Users’ UX

Aspects for VUI?

In total, we identified 32 UX aspects of intensive

users for VUIs (see Table 2). We specify them

through the statements of the interview participants,

which are available in the research protocol (K

¨

olln

et al., 2022). This way, they can be compared

with existing scales and terms based on the core

statements of the users, without requiring additional

associations from preceding research. In the results,

we consider only a single mentioning per participant

of a UX aspect. The number of mentions by a single

participant is not necessarily a measure of impor-

tance. Emphasis, context, and wording also provide

information on priority, but are hardly measurable.

For this reason, the evaluation was based on the

number of interview (see Table 2, column Int.) and

survey participants (see Table 2, column Sur.) who

mentioned a UX aspect. Due to the small number of

participants, we have decided not to set a minimum

number of participants who must have named a UX

aspect. It is possible that the distribution of numbers

could be different with a larger group of participants.

A few of our identified UX aspects had already

been defined throughout established literature, e.g.,

Efficiency and Effectivity (ISO 9241-210, 2019) or

Aesthetic (Schrepp and Thomaschewski, 2019a), but

not necessarily for VUIs. Other UX aspects are part

of other known UX factors, e.g., Simplicity and Polite-

ness, which may be part of the UX factor Likeability

Identifying User Experience Aspects for Voice User Interfaces with Intensive Users

391

of the Subjective Assessment of Speech System Inter-

faces (SASSI) (Hone and Graham, 2000), but are not

explicitly considered. Additionally, we did identify

several new UX aspects for VUIs, e.g., Independency

or Context-sensitivity.

Instead of following a theoretical approach on

what a UX aspect should mean, we followed a more

user-centered approach to identify UX aspects for

VUIs. These UX aspects represent what intensive

users think about when evaluating the UX of VUIs

and can be used, e.g., to choose the best UEQ+ scales

to combine with the VUI scales (Klein et al., 2020b)

4.4 Limitations

Our study is limited to a smaller group of participants,

which is put into perspective using a mixed-methods

approach. Despite being limited to ten interviews, this

study provides meaningful results in the qualitative

section, confirmed by the quantitative part of this sur-

vey. Below a sample size of twenty interviews, data

saturation usually appear (Francis et al., 2010).

We also have to consider, that our study has a gen-

der bias towards male participants. The unstable gen-

der distribution of the participants is because, e.g.,

females use VUIs less than males (SPLENDID RE-

SEARCH GmbH, 2019; Tas et al., 2019). The partic-

ipants are heterogeneous concerning the VUI usage

in professional and private locations as well as par-

ticipants with or without impairments, so we do not

expect relevant selection bias.

Although this study was internationally con-

ducted, most of our participants are from the West-

ern European region, specifically Germany and Spain.

The results of the study may be different with more

participants from, e.g., the Asian or African regions.

5 CONCLUSION & FUTURE

WORK

We explored the usage behavior as well as the expec-

tations and experiences of intensive users of VUIs.

This allowed us to make statements about the fre-

quency and reasons of use for the target group accord-

ing to our user-centered, mixed-methods approach.

Additionally, we were able to determine which UX

aspects the target group applies to evaluate VUIs.

We have found that many intensive users not only

use their VUI almost daily, but often even for sev-

eral hours a day. Most of the target group use VUIs

for comfort and to make their daily lives easier, e.g.,

in their smart home. Particularly noteworthy is the

potential of VUIs in supporting users with disabili-

ties. We created a list with 32 UX aspects for VUIs

of the target group. Although some of the terms are

already known, we explain the UX aspects from the

user’s point of view and what they expect from a VUI

regarding this UX aspect. Additionally, we were able

to identify several new UX aspects for VUIs.

Prioritization of these UX aspects should still be

performed in the future. We will use the UX as-

pects for VUIs in future work to determine which

UX measurement method considers which UX aspect.

Thereby, VUI designers can choose a UX measure-

ment method that fits their users’ needs. For example,

a comparison with the UEQ+ scales could show the

total scales needed to assess the UX of a VUI. This

would allow researchers to better adapt their method-

ology to the UX aspect they wish to evaluate.

REFERENCES

Biermann, M., Schweiger, E., and Jentsch, M. (2019). Talk-

ing to Stupid?!? Improving Voice User Interfaces.

In Fischer, H. and Hess, S., editors, Mensch und

Computer 2019 - Usability Professionals, pages 1–4,

Bonn. Gesellschaft f

¨

ur Informatik e.V. Und German

UPA e.V.

Bogner, A., Littig, B., and Menz, W. (2014). Interviews

mit Experten: Eine praxisorientierte Einf

¨

uhrung.

Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden.

Cohen, M. H., Giangola, J. P., and Balogh, J. (2004). Voice

User Interface Design. Addison-Wesley, Boston.

Dresing, T. and Pehl, T. (2018). Praxisbuch Interview, Tran-

skription & Analyse, Audiotranskription. Dr. Dresing

und Pehl, Marburg.

Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L.,

Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., and Grimshaw, J. M.

(2010). What is an adequate sample size? Opera-

tionalising data saturation for theory-based interview

studies. Psychology & Health, 25(10):1229–1245.

Hassenzahl, M. (2008). User experience (ux): Towards

an experiential perspective on product quality. IHM,

September 2008:11–15.

Hassenzahl, M. and Tractinsky, N. (2006). User experience

- a research agenda. Behaviour & Information Tech-

nology, 25(2):91–97.

Hone, K. S. and Graham, R. (2000). Towards a tool for

the subjective assessment of speech system interfaces

(sassi). Natural Language Engineering, 6(3&4):287–

303.

Iniesto, F., Coughlan, T., and Lister, K. (2021). Imple-

menting an accessible conversational user interface. In

Vazquez, S. R., Drake, T., Ahmetovic, D., and Yaneva,

V., editors, Proceedings of the 18th International Web

for All Conference, pages 1–5, New York, NY, USA.

ACM.

ISO 9241-210 (2019). Ergonomics of human-system

interaction Part 210: Human-centred de-

WEBIST 2022 - 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

392

sign for interactive systems. Technical report,

https://www.iso.org/committee/53372.html.

Klein, A. M., Hinderks, A., Schrepp, M., and

Thomaschewski, J. (2020a). Construction of

UEQ+ Scales for Voice Quality. In Proceedings of

the Conference on Mensch Und Computer, MuC ’20,

pages 1–5, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

Klein, A. M., Hinderks, A., Schrepp, M., and

Thomaschewski, J. (2020b). Measuring User

Experience Quality of Voice Assistants. In 2020

15th Iberian Conference on Information Systems

and Technologies (CISTI), pages 1–4, Seville, Spain.

IEEE.

Klein, A. M., Rauschenberger, M., Thomaschweski, J., and

Escalona, M. J. (2021). Comparing Voice Assistant

Risks and Potential with Technology-Based Users: A

Study from Germany and Spain. Journal of Web En-

gineering, 7(16):1991–2016.

Kocaballi, A. B., Laranjo, L., and Coiera, E. (2019). Un-

derstanding and measuring user experience in con-

versational interfaces. Interacting with Computers,

31(2):192–207.

K

¨

olln, K., Deutschl

¨

ander, J., Klein, A. M., Rauschenberger,

M., and Winter, D. (2022). Protocol for identifying

user experience aspects for voice user interfaces with

intensive users.

Langevin, R., Lordon, R. J., Avrahami, T., Cowan, B. R.,

Hirsch, T., and Hsieh, G. (2021). Heuristic evaluation

of conversational agents. In Kitamura, Y., Quigley,

A., Isbister, K., Igarashi, T., Bjørn, P., and Drucker,

S., editors, Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 1–15,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Mayring, P. (1994). Qualitative content analysis, volume

1994. UVK Univ.-Verl. Konstanz.

McKim, C. A. (2017). The value of mixed methods re-

search: A mixed methods study. Journal of Mixed

Methods Research, 11(2):202–222.

Meiners, A.-L., Kollmorgen, J., Schrepp, M., and

Thomaschewski, J. (2021). Which ux aspects are im-

portant for a software product? importance ratings

of ux aspects for software products for measurement

with the ueq+. In Mensch Und Computer 2021, MuC

’21, page 136139, New York, NY, USA. Association

for Computing Machinery.

Preece, J., Rogers, Y., and Sharp, H. (2002). Interaction

design: beyond human-computer interaction. In Inter-

action design: beyond human-computer interaction. J.

Wiley & Sons, New York.

Pyae, A. and Joelsson, T. N. (2018). Investigating the us-

ability and user experiences of voice user interface.

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference

on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices

and Services Adjunct, pages 127–131, New York, NY,

USA. ACM.

Rauschenberger, M. (2021). Acceptance by Design : Voice

Assistants. In 1st AI-DEbate Workshop : work-

shop establishing An InterDisciplinary pErspective on

speech-BAsed TEchnology, page 27.09.2021, Magde-

burg, Germany. OvGU.

Schrepp, M. and Thomaschewski, J. (2019a). Construction

and first validation of extension scales for the user ex-

perience questionnaire (ueq).

Schrepp, M. and Thomaschewski, J. (2019b). Design

and Validation of a Framework for the Creation of

User Experience Questionnaires. International Jour-

nal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelli-

gence, 5(7):S. 88–95.

Sciuto, A., Saini, A., Forlizzi, J., and Hong, J. I. (2018).

hey alexa, whats up?: A mixed-methods studies of in-

home conversational agent usage. In Proceedings of

the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference,

DIS 18, page 857868, New York, NY, USA. Associa-

tion for Computing Machinery.

Seaborn, K. and Urakami, J. (2021). Measuring voice ux

quantitatively. In Kitamura, Y., Quigley, A., Isbister,

K., and Igarashi, T., editors, Extended Abstracts of the

2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, pages 1–8, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

SPLENDID RESEARCH GmbH (2019). Digitale

Sprachassistenten.

Strategy Analytics (2021). Absatz von intelligenten laut-

sprechern weltweit vom 3. quartal 2016 bis zum 3.

quartal 2021.

Tas, S., Hildebrandt, C., and Arnold, R. (2019). Voice As-

sistants in Germany. WIK Wissenschaftliches Institut

f

¨

ur Infrastruktur und Kommunikationsdienste GmbH,

Bad Honnef, Germany. Nr.441.

Wei, Z. and Landay, J. A. (2018). Evaluating speech-based

smart devices using new usability heuristics. IEEE

Pervasive Computing, 17(2):84–96.

Winter, D., Hinderks, A., Schrepp, M., and

Thomaschewski, J. (2017). Welche UX Fak-

toren sind f

¨

ur mein Produkt wichtig? In Hess,

S. and Fischer, H., editors, Mensch und Computer

MuC 2017. Gesellschaft f

¨

ur Informatik e. V. und die

German UPA e.V.

Identifying User Experience Aspects for Voice User Interfaces with Intensive Users

393