Agile in Higher Education: How Can Value-based Learning

Be Implemented in Higher Education?

Eva-Maria Schön

1a

, Ilona Buchem

2b

and Stefano Sostak

3c

1

Faculty Business Studies, University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer, Constantiaplatz 4, Emden, Germany

2

Faculty I Economics and Social Sciences, Berlin University of Applied Sciences, Berlin, Germany

3

Gorillas B.V. & Co KG, Berlin, Germany

Keywords: Agile, Value-based Learning, Student-Centered Learning, Teaching.

Abstract: The corona pandemic has shown how important it is to be able to react quickly to changing conditions. In

many organizations, agile process models and agile practices are used for this purpose. This paper examines

how agility can be implemented in higher education. Using two case studies, we analyze how agile practices

and agile values are implemented for knowledge and skills development. Our results present a student-

centered approach where lecturers supported self-organized learning. In the student-centered approach, prior

knowledge and experience of learners are taken into account, and the learning process is adjusted through

continuous feedback. With the introduction of agility, a value shift towards value-based learning is taking

place. Value-based learning supports competency-based teaching since the focus is less on imparting technical

knowledge and more on imparting competencies.

1 INTRODUCTION

The corona pandemic has brought nearly the entire

world into the home office and also turned teaching

in schools and universities upside-down. While some

of the lessons in schools are still held face-to-face

with changing groups, colleges and universities have

largely switched to digital teaching and exam

formats. This changeover has taken place in a short

period of time and poses challenges for both teachers

and students. The survey of students and teachers on

the first corona semesters by the CHE Center for

Higher Education Development showed that students

praised the variety of different digital formats, but at

the same time wished for better didactic

implementation and a motivating approach by

teachers (Berghoff et al., 2021). The results of the

study also show that both students and lecturers

would like to see blended learning and digitally

enriched face-to-face teaching in the future. In

addition to quantitative studies on teaching during the

corona pandemic, qualitative studies such as the HFD

working paper (Bosse, 2021) broaden the perspective

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0410-9308

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9189-7217

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3671-7551

on this topic. Bosse (Bosse, 2021) used interviews to

assess different departments, including social

sciences and economics, about their experiences with

the transition to online teaching during the pandemic

and their expectations for the future. The results show

a desire for curriculum development with the teaching

of competencies relevant to the digitized world as

well as consistent use of digital tools and the

development of new room concepts.

The shift to digital teaching has driven digital

transformation in higher education institutions as new

teaching and learning formats are tested and

collaborative technologies such as MS Teams, Zoom,

Miro, or Mentimeter are more widely used.

Experiences from past digital semesters provide a

good opportunity for lecturers to redesign their

teaching strategies in the digital age. As digitization

continues, traditional value systems are also being

challenged and are constantly changing. In the

economy, this is reflected in the increasing spread of

agile process models in all industries (Digital.ai,

2021). Organizations use agile process models to

solve complex problems and to be able to react

Schön, E., Buchem, I. and Sostak, S.

Agile in Higher Education: How Can Value-based Learning Be Implemented in Higher Education?.

DOI: 10.5220/0011537100003318

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2022), pages 45-53

ISBN: 978-989-758-613-2; ISSN: 2184-3252

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

45

quickly to changes in the environment. Agile process

models originated in software development and are

increasingly being used in areas outside of IT. For this

purpose, agile process models such as Scrum

(Schwaber et al., 2020) or Kanban (Anderson, 2010)

are adapted to other areas (Pfeiffer et al., 2016),

(Schön, 2018). A well-known example is represented

by eduScrum® (Stolze et al., 2020). With

eduScrum®, the Scrum framework was adapted for

the education sector and a co-creative process was

developed in which students feel responsible for their

own work and learning process.

This paper examines the research question: How

can agility be implemented in higher education? The

context of higher education has also been changing at

an accelerating pace in recent years, requiring

lecturers to explore new ways to support students in

acquiring knowledge and skills. To answer the

research question, we examine concepts for

integrating agile practices and agile values in higher

education using two case studies at German

universities of applied sciences in Berlin and

Hamburg.

This paper is structured as follows: section 2

provides a brief overview of theoretical concepts of

agile models and didactics. Section 3 describes the

research method for the two case studies conducted.

Section 4 presents our results and shows how agile

practices and agile values were implemented in

higher education in the two case studies. Then,

section 5 discusses similarities and differences.

Section 6 concludes this work with a summary and

future work.

2 BACKGROUND

In the following, we provide a brief overview of

theoretical concepts of agile process models and agile

practices as well as didactic concepts.

2.1 Agile Process Models and Agile

Practices

“Agile is the ability to create and respond to change.

It is a way of dealing with, and ultimately succeeding

in, an uncertain and turbulent environment.” (Agile

Alliance, 2020)

Agile process models have become a highly

discussed and popular topic in recent years. Many

organizations today are already using agile process

models and agile practices. Agile practices are

concrete procedures for implementing agile values

and principles. Agile values refer to a value set that is

used as a basis for the application of agile process

models. Originally, the agile values were captured in

the Agile Manifesto with four values (cf. individuals

and interactions, working software, customer

collaboration, responding to change) (Beck et al.,

2001). Agile process models such as Scrum

(Schwaber et al., 2020) or Kanban (Anderson, 2010)

have their origins in software development. In IT,

these models have been used for decades to solve

complex problems. The use of agile process models

is intended to increase transparency and accelerate

change, as well as minimize risks and errors in the

development process. To this end, it is attempted to

reduce the design phase to a minimum and to achieve

executable software as early as possible in the

development process. In comparison to plan-oriented

approaches, such as the waterfall model, the iterative

development and testing of incremental solutions and

the collection of feedback are in the foreground in

agile process models. This approach requires a

change of mindset, because solutions are not planned

in detail in advance, but are developed and optimized

on an ongoing basis and the basis of feedback from

relevant stakeholders.

Agile process models are also being used more

and more frequently in other areas outside IT, as

presented in the annual State of Agile study

(Digital.ai, 2021). The study shows that

organizational culture in particular has an influence

on the successful use of agility. Furthermore, it

becomes clear that resistance to change and a lack of

understanding of the agile mindset are often

problematic for the introduction of agility within an

organization. The agile mindset encompasses

fundamental assumptions such as believing in the

competence and responsibility of individuals,

encouraging collaboration, continuous learning and

improvement, encouraging creativity, promoting

innovation, and taking moderate risks (cf. Tolfo et al.,

2011). The agile mindset and the adaptation of agile

values, principles and practices are also interesting

for higher education didactics, as autonomous,

project-based and iterative learning in short cycles

with continuous feedback can support the

development of competencies in higher education.

2.2 Didactic Concepts

Didactic concepts for agility in higher education are

still a relatively, young field of practice and research.

On the one hand, there are concepts for agile didactics

in the sense of agile interactions of teachers and

learners in the classroom, and on the other hand,

didactic concepts for integrating agile practices from

WEBIST 2022 - 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

46

the field of software development into other subject

areas of higher education. As an example of concepts

for agility in higher education, the book Agile

University Didactics is often cited (Arn, 2020), in

which agile didactics, in contrast to planned didactics,

is defined as a mixture of planned and unplanned

teaching, a didactics that emerges from

communication and interaction, especially when

learners and teachers not only meet at eye level but

encounter each other openly (Arn, 2020). In this

approach, lecturers play the dual role of teachers and

coaches at the same time. They teach according to the

principle of structured improvisation and react to the

feedback of the learners in analogy to the interaction

with customers in agile software development (Arn,

2020).

Agile principles are used in different contexts and

disciplines, e.g. in economics with the aim to improve

lifelong learning and employability of students

(Cubric, 2013), in doctoral studies to support

collaborative learning between doctoral students

(Stewart et al., 2009, Schön, 2018), and at the

university with the aim to improve studying and

teaching (Mayrberger et al., 2017). Other didactic

concepts in higher education rely on methods of agile

software development and propose concepts and

principles for the redevelopment of universities. For

example, Baecker, (2017) emphasizes the conversion

from primarily vertical to primarily horizontal

organizational structures and acting in networks at

universities in the sense of scientific communities as

well as a stronger interlocking with professional

practice. This approach can be transferred both to the

management structures at universities and to the

design of teaching, in which not only one teacher is

involved, but different teachers interact, as the case

study at Berlin University of Applied Sciences shows.

Based on agile approaches and process models

such as Scrum, didactic methods such as eduScrum®

are also being developed and used. Here, eduScrum®

is described as a framework for coaching learners in

which the responsibility for the learning process is

transferred to the learners (Stolze et al., 2020).

eduScrum® is based, similar to Scrum, on the

collaboration of teams with the associated

descriptions of roles, ceremonies, artifacts, and rules.

Another example is the Agile Manifesto for Teaching

and Learning by Krehbiel et al., (2017), which defines

the agile principles, concepts and practices for higher

education in analogy to the Agile Manifesto from

software development. The objective is to increase

student engagement, encourage students to take

responsibility for learning, improve the level and

quality of collaboration, and produce high-quality

results in teaching. With a similar objective, the

concept of agile learning with Just in Time Teaching

(JiTT) is also proposed, which builds on the

principles of constructivism and self-determination

theory and emphasizes adaptive teaching with

coupled teaching-learning cycles and continuous

feedback loops (Meissner et al., 2014).

3 RESEARCH METHOD

This paper investigates the research question: How

can agility be implemented in higher education? To

this end, we conducted two case studies at two

universities of applied sciences in Germany during

the corona pandemic. Therefore, we examine

concepts for integrating agile process models and

agile practices in digital studies using two case

studies from universities in Berlin and Hamburg.

Complex phenomena with their respective contexts

are investigated in case studies (Baxter et al., 2008,

Yin, 2003). A case study allows us to collect data in

practice to better understand the context of higher

education.

3.1 Context of Case Study 1 - Berlin

University of Applied Sciences

Berlin University of Applied Sciences is a public,

technical University of Applied Sciences with around

13,000 students and over 70 accredited bachelor's and

master's degree programs in the fields of applied

engineering, natural sciences and economics. Key

qualifications such as the ability to work in a team and

social skills play a central role in the studies. The use

of digital technologies in teaching is part of the

university's digitization strategy.

The case study examined involves the mandatory

module Agile Project Management (6 CP with 4

SWS) in the degree program Business Administration

Digital Economy (B. Sc.), in the departments of

Economics and Social Sciences. The students are

rather interested in technology, but generally have

little to no prior knowledge of agile principles and

methods.

3.2 Context of Case Study 2 - HAW

Hamburg

HAW Hamburg is a public University of Applied

Sciences in northern Germany with over 70

accredited bachelor's and master's degree programs.

In the winter semester of 2020/2021, there were a

Agile in Higher Education: How Can Value-based Learning Be Implemented in Higher Education?

47

total of 17,125 enrolled students. HAW Hamburg

pursues the goal of developing sustainable solutions

for the social challenges of the present and the future.

The case study is the optional course Agile Project

Management (6 CP with 4 SWS), which is offered at

the Faculty of Technology and Information

Technology primarily for Bachelor students in the 5th

or 6th semester of the degree program Business

Informatics (B.Sc.). Students of other study programs

can also participate in the module, as far as the

capacities allow. Thus, the target group of the module

is rather technically affine and already has some prior

knowledge regarding agile process models.

3.3 Data Collection and Analysis

These two case studies were conducted during the

summer semester 21. Due to the corona pandemic,

digital teaching was conducted this semester and the

teaching and learning concepts were tailored

accordingly to the digital format. For the data

collection, an analysis of the course material of the

case studies was carried out. The course material was

analyzed with regard to didactic goals, teaching

concepts and methods as well as learning controls. In

addition, the extent to which agile practices and agile

values were applied in the course was examined. The

results of this analysis are presented in the form of a

narrative comparison in the following chapter. For

better comparability of the two case studies, a table is

created that presents an overview of implemented

agile practices and agile values.

4 RESULTS

In the following, the two case studies are described

and an analysis is made with regard to agile practices

and agile values.

4.1 Case Study 1 - Berlin University of

Applied Sciences

The Agile Project Management module at Berlin

University of Applied Sciences is a mandatory module

in the 3rd semester of the Business Administration

Digital Economy degree program and is offered

entirely in English in order to strengthen the

internationality in the degree program and prepare

students for working in international projects. In the

following, a description of the didactic goals, the

teaching concept and methods, as well as the learning

assessments and digital awards are given. In addition,

it will be explained how agile practices and agile

values have been implemented.

4.1.1 Didactic Goals

The learning objectives of the module were

developed as learning outcomes in the sense of

competence orientation in orientation to the revised

learning objectives taxonomy of (Anderson et al.,

2001) and formulated in the module handbook as

follows: (1) students know theoretical and

methodological basics of agile project management,

they can classify agile project management as a

methodological approach and compare it with other

approaches; (2) students have a general overview of

the central frameworks, methods, instruments and

application areas of agile project management in

business management practice; (3) students can apply

methods, instruments and decision-making tools of

agile project management in practice, taking into

account agile values and principles; (4) students are

able to plan and implement projects according to the

agile approach, evaluate and present the results.

4.1.2 Teaching Concepts and Didactic

Methods

The module Agile Project Management is based on

teamwork in small groups and its content is

interlinked with the module project seminar

marketing. Students work on projects from the project

seminar marketing and apply methods of agile project

management in the course.

The module consists of a seminar class (SC) and

a tutorial (T) with integrated project work. The

module is instructed by two lecturers, a professor

from the Berlin University of Applied Sciences (SC)

and a lecturer from the business world (T). The grade

for the module is composed of three sub-grades. The

A-grade is assigned to the SC and accounts for 40%

of the final grade. The A-grade is determined based

on the results of the eight online quizzes in terms of

continuous learning assessments. The B-grade is

assigned to the tutorial and also accounts for 40% of

the final grade. The B-grade is determined based on

team coaching sessions (8 sessions per team). In

addition, students can earn 5 bonus points in team

coaching. The C-grade is considered a common sub-

grade in the SC and the T and accounts for 20% of the

overall grade. The C-grade is based on the evaluation

of the final video reflection (one video per team).

Seminar class (SC): In the SC, the content on agile

project management is taught and basic agile

principles are learned, including project management

in transition; characteristics and types of projects in

WEBIST 2022 - 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

48

the digital economy; project leadership in the digital

age; agile values, mindset and principles; agile

frameworks such as Scrum, Kanban and DSDM. The

instructional design from SC is based on the ARCS

model, a motivational instructional design approach

from (Keller et al., 1987) with four basic principles:

attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction.

Various didactic methods are used in teaching,

including flipped classroom (i.e., preparation for SC

with learning videos, application in SC, follow-up

with learning scripts, weekly quizzes), game-based

learning (e.g., games for applying agile frameworks),

and collaborative learning in project teams. Various

digital learning materials are used to best support

students with different learning styles and

preferences, including interactive presentation slides

in Google Drive, scripts in PDF format in the Moodle

LMS, and learning videos on LinkedIn Learning.

Tutorial (T): In addition to the SC, there is a

weekly T for the students. The aim of the 90-minute

T is to deepen the knowledge gained in the SC and

supplement it with practical experience. Agile

working is to be made experienceable. This is done

by presenting and applying methods from the work

with agile project teams in software companies, as

well as creating a framework for agile collaboration

of the students on the projects in the marketing

seminar. The T is divided into five parts: warm-up,

knowledge reinforcement, team time, Lean Coffee,

and query of Return Of Time Invested (ROTI). The

warm-up takes place at the beginning of each T and

serves to activate the students. It includes an activity

to promote group interaction at the beginning of each

T (Przybylek et al., 2017). This common warm-up

creates a positive working atmosphere in the group. It

also increases the receptivity of the participants

(Mesquida et al., 2017). Typically, the warm-up lasts

five to 15 minutes and includes a previously

unfamiliar activity. This activity aims at a cognitive

stimulation of the students. The knowledge deepening

sub-section is about deepening the content learned in

the SC, which is complemented by practical case

studies. During team time, students work in their

teams on their specific projects for the marketing

project seminar. This gives students the opportunity

to apply what they have learned directly to their

project work. Lean Coffee is an agile practice that

facilitates discussions with minimal planning. It uses

innovative voting techniques such as dot voting to

support collaboration and the decision-making

process (Dalton, 2019). In Lean Coffee, students have

the opportunity to raise issues relevant to them and

discuss them with the lecturer and other students in

the course. At the end of each T, a survey of ROTI

was conducted. This asked students to indicate their

personal return on time invested in the T on a scale of

one to five. A rating of five indicates a very high

return on time invested. Students were also asked to

indicate what they lacked for a better rating if they

scored below five. This allows instructors to

iteratively adjust and improve the structure of the T.

Other methods include clarification of individual

expectations and two team retrospectives.

4.1.3 Learning Assessments and Digital

Awards

In the SC, there are weekly quizzes in Moodle as

continuous learning assessments to test the

knowledge on the central topics in Agile Project

Management week by week. The quizzes are created

in the LMS Moodle. Different question formats are

used, including multiple-choice, assignment, drag &

drop. In the exercise, starting from the answer to the

ROTI survey, the students' participation in the

exercise will be checked. Students will receive 5

points for each participation. In addition, students can

earn 5 bonus points by facilitating a team

retrospective. The end-of-semester video reflection

will be graded on a criterion-referenced basis. Each

team will create a 10-minute video in which each

team member reflects on the agile work in the team,

including the use of agile methods and tools,

according to the following criteria: (1) agile team (2)

agile principles (3) agile methods and tools (4)

takeaways.

In the Agile Project Management module, two

additional digital awards based on Open Badges in

the Moodle LMS are given to students who have met

certain requirements. Students who have achieved the

maximum score in the A-grade (knowledge-based

learning assessment) will receive an agile expert

digital badge. Students who have achieved the

maximum score in the B-grade (team coaching) will

receive an agile team digital badge. In addition,

students will be guided on how to use the digital

badges for profiling on social media, e.g. on

LinkedIn.

4.2 Case Study 2 - HAW Hamburg

In the following, a description of the didactic goals,

the teaching concept and methods, and the learning

assessments are provided. In addition, it is explained

how agile practices and agile values were

implemented.

Agile in Higher Education: How Can Value-based Learning Be Implemented in Higher Education?

49

4.2.1 Didactic Goals

The learning objectives of the course have been

formulated as learning outcomes within the

framework of competency-based teaching. For the

presentation, a user story (Cohn, 2004) has been

created and presented by means of a sketchnote (see

Figure 1). For the formulation of the acceptance

criteria, the taxonomy levels according to (Bloom et

al., 1956) have been used. The goal is for students to

be able to apply as many agile practices and agile

values as possible during the course.

Figure 1: Learning objectives in the user story format.

4.2.2 Teaching Concepts and Didactic

Methods

The optional module Agile Project Management is

divided into 2 SWS seminar classes (SC) and 2 SWS

tutorials (T). The module is taught by a professor

from HAW Hamburg. The professor brings both the

expertise and the application knowledge from

corporate practice. In addition, there are guest

lectures by well-known personalities of the agile

community from industry and science within the

framework of the SC.

Seminar class (SC): In the SC, the theoretical

basics of agile project management are provided. The

following topics are covered: agile mindset, state of

agile in practice, product discovery and product

execution, agile estimation and planning, agile

process models, scaling agile, and agile leadership.

Theoretical concepts are introduced and content is

supplemented with videos and interactive discussions

to implement activating teaching. In summer

semester 21, there were two guest contributions from

people in industry and academia who reported on

agility in practice and current research on the agile

way of working during the corona pandemic.

Tutorial (T): The tutorial consists of three

exercise units which are assessed with a pre-requisite

for the exam. The tutorial has been implemented by

means of a sprint logic. The duration of a sprint is

three weeks. During the SC, the new tasks are

presented (planning). The students then work on the

tasks in self-organized teams (doing). A shared

exercise date is then used for the teams to present the

results to each other and receive feedback (review).

At the end of the exercise, a retrospective takes place

in which the participants reflect together on what

went well, what can be optimized and what was

learned. The lecturer takes on the role of the product

owner in the T and presents the tasks to be worked on

and accepts the solutions at the end. During the first

T, the students conduct a product discovery and apply

the agile practices personas, story maps, and user

stories. During the second T, students perform agile

estimation and release planning. Here, the agile

practices magic estimation, release planning using a

story map and minimum viable product (MVP) are

applied. In the third T, a release retrospective is

conducted with the entire course in order to reflect on

learning outcomes and thus consolidate the content in

the long-term memory.

4.2.3 Learning Assessments

Different methods are used to assess the learning

progress. On the one hand, interactive quizzes are

regularly included in the SC; these can be group

discussions as well as smaller surveys or quizzes. On

the other hand, the students apply the contents of the

SC in the T. Another aspect is the exam of the

semester. The form of exam used is a presentation.

The students independently choose a topic from the

SC and create a scientific poster. The scientific poster

is presented in an audio presentation.

The course Agile Project Management was

conducted completely digitally due to the pandemic

regulations valid in the summer semester of 2020.

The following tools were used to conduct the digital

teaching: Miro, Trello, Retromat, MS Teams, Zoom,

Whiteboard, and Mentimeter.

5 DISCUSSION

In this section, we discuss the implications of our

findings and answer our research question of how

agility can be implemented in higher education.

5.1 How Can Agility Be Implemented

in Higher Education?

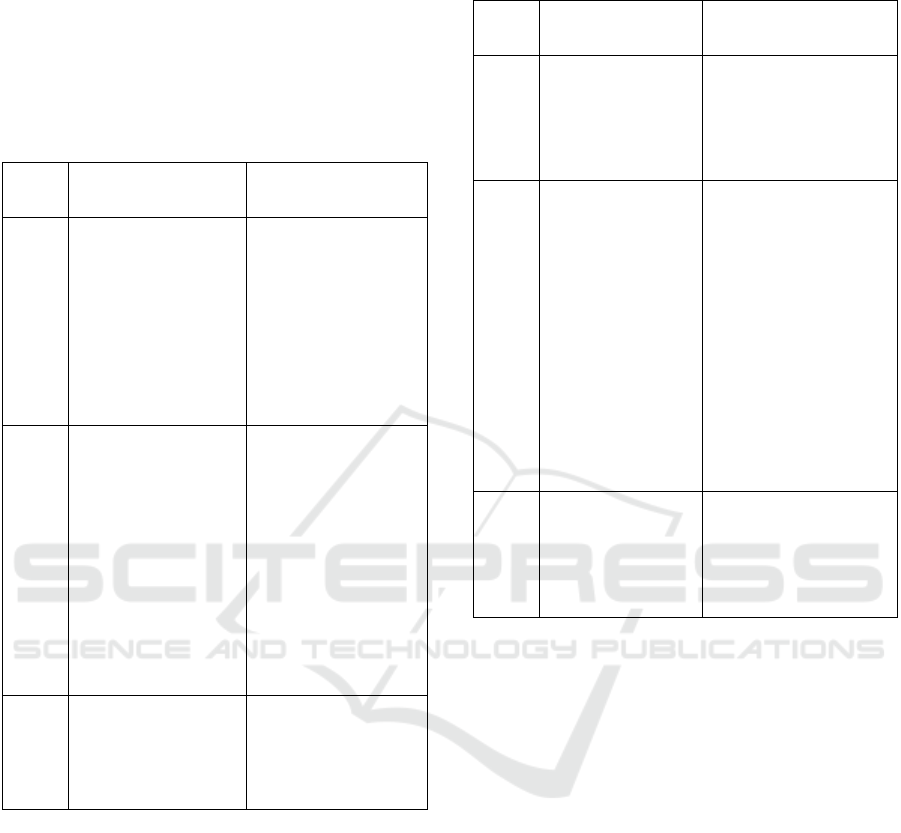

The analysis of the case studies (cf. section 4) has

shown how agile practices can be used in higher

education. We have conducted a comparison of the

WEBIST 2022 - 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

50

agile practices and agile values used in the two case

studies. Table 1 shows an overview of the

implemented agile practices and agile values in case

study 1 (Berlin University of Applied Sciences) and

Table 2 shows the results for case study 2 (HAW

Hamburg).

Table 1: Overview of agile values and agile practices in

case study 1.

Didactic

element

Agile values Agile practices

Seminar class (SC)

individuals and

interactions over

processes and tools,

customer

collaboration over

contract negotiation,

responding to change

over following a plan

scrum team, scrum

events, product

backlog, team board,

timebox, user story,

estimation, querying

expectations,

gathering feedback,

iteratively responding

to student needs and

feedbac

k

Tutorial (T)

individuals and

interactions over

processes and tools,

customer

collaboration over

contract negotiation,

responding to change

over following a

plan, working

software over

comprehensive

documentation

team building, team

phases, scrum events,

Lean Coffee,

retrospective, asking

for expectations,

collecting feedback,

iteratively responding

to student needs and

feedback, timebox,

project slicing, story

mapping, team time

to work on the

marketin

g

p

ro

j

ect

Exam

individuals and

interactions over

processes and tools

collaborative

reflection

With the introduction of agility into higher

education, the role of lecturers, students and the

interaction between these group changes. Lecturers

are seen as coaches who provide students with a

roadmap (e.g., didactic goals and course material) for

acquiring knowledge and skills. They accompanied

the students' learning process and are available as

advisors.

In addition, they motivated the students and

supported them in self-organized learning. In agile

process models, this role is also known as team coach

(Hawkins, 2021). The role of the learner also changes,

as a change in values takes place with the introduction

of agility and teaching evolves into a student-centered

approach, in which the students with their prior

knowledge

and attitudes regarding learning are the

Table 2: Overview of agile values and agile practices in

case study 2.

Didactic

element

Agile values Agile practices

Seminar class

(SC)

individuals and

interactions over

processes and

tools, responding

to change over

following a plan

product backlog,

kanban board, timebox,

user story, informal

documentation,

sketchnotes,

storytelling

Tutorial (T)

individuals and

interactions over

processes and

tools, working

software over

comprehensive

documentation,

openness, respect,

courage

product owner,

timebox, sprint logic,

planning meeting,

review meeting,

retrospective, user

story, product

discovery, personas,

story maps, agile

estimation and

planning, magic

estimation, story points,

release plan-ning,

minimum viable

product, release

retros

p

ective

Exam

individuals and

interactions over

processes and

tools, autonomy,

mastery and

p

urpose

timebox

focus. In both case studies (see chapters 4.1 and 4.2),

regular feedback was obtained from the students in

order to adapt the subsequent learning units to the

needs of the learners during the semester. Care is

always taken to ensure that the changes in the

teaching concept meet the requirements of the Agile

Project Management module in terms of content and

do not blur it. The regular collection of feedback from

the students serves as quality control of the iteration

process. Furthermore, the lecturers try to promote the

intrinsic motivation of the students and use didactic

concepts, e.g. growth mindset (Claro et al., 2016), so

that agile values such as autonomy, mastery, and

purpose (Pink, 2009) come into focus. This shift in

values towards value-based learning supports

competency-based teaching, as the focus is less on

teaching subject knowledge and more on teaching

competencies.

In addition, the linking of the Agile Project

Management module with other modules in case

study 1 makes it possible to apply and deepen the

teaching content across modules. In this way, students

benefit in several ways from what they have learned.

They experience the value-creating character of agile

Agile in Higher Education: How Can Value-based Learning Be Implemented in Higher Education?

51

working through the theory, as well as through

personal successes, e.g. positive feedback from the

customer in the marketing project seminar and/or

through a better grade.

5.2 Critical Review and Limitations

When using the taxonomies of cognitive learning

objectives, the affective level, (e.g. attitudes and

motivation), is currently missing in the learning

objective description. However, this level of learning

objectives is important if we want to develop attitudes

in orientation to values more strongly and integrate

them into the curricula. In future courses, we,

therefore, want to expand the learning objectives

descriptions by using other taxonomies that deal

specifically with attitudes and motivation. Thus, the

student-centered approach can be further improved.

The results are currently based on an analysis of

the authors' course material, as well as an evaluation

of learning assessments carried out. The agile

practices and agile values used (see Table 1 and Table

2) might have been perceived differently by the

students. We have increased the objectivity of the

analysis by having a discussion of the results in the

authors' group.

This research has so far been limited to the context

of higher education, as we have conducted the case

studies in higher education institutions. Value-based

learning is also suitable for other teaching and

learning contexts, such as adult education and also

other types of schools. However, this needs to be

evaluated in future studies. In addition, the authors

have already gained experience in how agile practices

and agile values can be incorporated into teaching in

other modules like programming, and information

systems. This is not part of the scope of this work as

the comparable data have not yet been evaluated.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper provides insights into how agility can be

implemented in higher education. For this purpose,

two case studies in Germany at Berlin University of

Applied Sciences and HAW Hamburg were

investigated. In both case studies, the Agile Project

Management module was analyzed in relation to the

respective context. We highlighted new ways to

support knowledge and skills acquisition that enable

rapid response to changing contexts through the use

of agile practices and agile values. Our results present

a student-centered approach to competency

development.

The implementation of agile working methods in

higher education leads to a change in values and thus

also to changes in the roles of lecturers and students.

In the future, lecturers will be seen as coaches who

accompany the learning process of students and

support them in their self-organized learning. In

comparison, teaching will evolve towards a student-

centered approach, where students with their prior

knowledge and attitudes towards learning will be the

focus. To this end, the learning process is adapted

with the help of continuous feedback. Thus, the role

of the learner also changes.

In future research, we want to collect further

empirical data on these two case studies in order to

gain more in-depth knowledge regarding the change

in values. In addition, we want to expand our learning

objectives for the modules so that the affective level,

including attitudes and motivation, is more strongly

considered in the description of the learning

objectives.

REFERENCES

Agile Alliance, X. (2020). What is Agile? What Is Agile?

Retrieved from https://www.agilealliance.org/agile101/

Anderson, D. J. (2010). Kanban - Successful Evolutionary

Change for your Technology Business. Sequim,

Washington: Blue Hole Press.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A Taxonomy

for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of

Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives:

Complete Edition. New York: Longman.

Arn, C. (2020). Agile Hochschuldidaktik (3. Auflage).

Juventa Verlag GmbH.

Baecker, D. (2017). Agilität in der Hochschule. Die

Hochschule. Journal Für Wissenschaft Und Bildung.

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study

methodology: Study design and implementation for

novice researchers. In The Qualitative Report (Vol. 13,

Issue 4).

Beck, K., Beedle, M., van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A.,

Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., Grenning, J., Highsmith,

J., Hunt, A., Jeffries, R., Kern, J., Marick, B., Martin,

R., Mellor, S., Schwaber, K., Sutherland, J., & Thomas,

D. (2001). Manifesto for Agile Software Development.

Retrieved from http://www.agilemanifesto.org/

Berghoff, S., Horstmann, N., Hüsch, M., & Müller, K.

(2021). Studium und Lehre in Zeiten der Corona-

Pandemie. Die Sicht von Studierenden und Lehrenden

(Issue CHE Impulse Nr. 3).

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., &

Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational

objectives: The classification of educational goals.

Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David

McKay Company.

WEBIST 2022 - 18th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

52

Bosse, E. (2021). Fachbereiche und Fakultäten in der

Corona-Pandemie. Erfahrungen und Erwartungen an

die Zukunft (Issue 57). Berlin.

Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Growth

mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic

achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences of the United States of America, 113(31),

8664–8668.

Cohn, M. (2004). User Stories Applied: For Agile Software

Development.

Cubric, M. (2013). An agile method for teaching agile in

business schools. The International Journal of

Management Education, 11(3), 119–131.

Dalton, J. (2019). Lean Coffee. In Great Big Agile (pp.

191–192). Berkeley, CA: Apress.

Digital.ai. (2021). 15th State of Agile. Retrieved from

https://digital.ai/resource-center/analyst-reports/state-

of-agile-report

Hawkins, P. (2021). Leadership team coaching:

Developing collective transformational leadership.

Kogan Page Publishers.

Keller, J. M., & Kopp, T. W. (1987). An application of the

ARCS Model of Motivational Design. In C. M.

Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional theories in action.

Lessons illustrating selected theories and models (pp.

289–320). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,

Inc.

Krehbiel, T., Salzarulo, P., Cosmah, M., Forren, J., Gannod,

G., Havelka, D., Hulshult, A., & Merhout, J. (2017).

Agile Manifesto for Teaching and Learning. The

Journal of Effective Teaching, 17(2), 90–111.

Mayrberger, K., & Slobodeaniuk, M. (2017). Adaption

agiler Prinzipien für den Hochschulkontext am Beispiel

des Universitätskollegs der Universität Hamburg.

Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation. Zeitschrift Fur

Angewandte Organisationspsychologie, 48(3), 211–

216.

Meissner, B., & Stenger, H.-J. (2014). Agiles Lernen mit

Just-in-Time-Teaching . Adaptive Lehre vor dem

Hintergrund von Konstruktivismus und intrinsischer

Motivation. O. Zawacki-Richter, D. Kergel, N.

Kleinefeld, P. Muckel, J. Stöter, & K. Brinkmann

(Eds.), Teaching Trends 2014. Offen für neue Wege:

Digitale Medien in der Hochschule (pp. 121–136).

Münste: Waxmann.

Mesquida, A.-L., Karać, J., Jovanović, M., & Mas, A.

(2017). A Game Toolbox for Process Improvement in

Agile Teams. In J. Stolfa, S. Stolfa, R. O’Connor, & R.

Messnarz (Eds.), Systems, Software and Services

Process Improvement. EuroSPI 2017. Communications

in Computer and Information Science (pp. 302–309).

Pfeiffer, T., Hellmers, J., Schön, E.-M., & Thomaschewski,

J. (2016). Empowering User Interfaces for Industrie

4.0. Proceedings of the IEEE, 104(5), 986–996.

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The Surprising Truth About

What Motivates Us. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

Przybylek, A., & Kotecka, D. (2017). Making agile

retrospectives more awesome.

Proceedings of the 2017

Federated Conference on Computer Science and

Information Systems, FedCSIS 2017, 11, 1211–1216.

Schön, E.-M. (2018). How Do Agile Practices Support

Organizing a Ph.D.? IT Professional, 20(6), 82–86.

Schwaber, K., & Sutherland, J. (2020). The Scrum Guide

(Issue v7).

Stewart, J. C., DeCusatis, C. S., Kidder, K., Massi, J. R., &

Anne, K. M. (2009). Evaluating agile principles in

active and cooperative learning. Student-Faculty

Research Day, CSIS, Pace University, May, B3.1 –

B3.8.

Stolze, A., & Fritsch, K. (2020). The eduScrum® Guide.

Tolfo, C., Wazlawick, R. S., Ferreira, M. G. G., &

Forcellini, F. A. (2011). Agile methods and

organizational culture: reflections about cultural levels.

Journal of Software Maintenance and Evolution:

Research and Practice, 23(6), 423–441.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: design and

methods. In Applied Social Research Methods Series

(Vol. 5). SAGE Publications.

Agile in Higher Education: How Can Value-based Learning Be Implemented in Higher Education?

53