Consequences of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lebanese Adolescents’

Experience of eLearning: A Call to Action

Nadine Daibess

a

, Nabil Georges Badr

b

, Joumana Yeretzian

c

and Michele Asmar

d

Higher Institute of Public Health, Saint Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon

Keywords: eLearning, Adolescent Learning Experience, Lifestyle Disruption, COVID-19 Lockdown.

Abstract: In general, adolescents are vulnerable to lifestyle changes, with implications on their physical and mental

health. During COVID-19 lockdown, mental disorders emerged among the Lebanese youth, with prevalence

of psychiatric symptoms related to insomnia, depression, and anxiety. The case of the adolescent population

in Lebanon was alarming. Suicidal intentions appeared among Lebanese adolescents from 9th to 12th grades.

Our study identifies depressive tendencies, stress and anxiety indicators in the respondents remarks. Our

adolescent informants have volunteered a few suggestions for coping strategies. Following knowledge to

action theory we provide some insight into call to action. Based on the findings from a qualitative review, we

organize some insights to promote the development of the adolescent condition in a challenging eLearning

environment. Finally, based on the comments from our students, we suggest that eLearning needs to be

personalized, on demand, and gamified to keep our adolescent learners engaged.

1 INTRODUCTION

After its emergence from China in December 2019,

the World Health Organization (WHO) declared

COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease) a global pandemic

on March 11, 2020. As a result, the WHO imposed a

confinement in form of a series of lockdowns that

spanned two academic years, to limit the spread of the

virus. Consequently, for adolescent learners, distance

learning became the option of reference to contain the

spread of the virus and to overcome the disruption of

the academic year (Salmi, 2020). Diverse psychiatric

disorders have alarmingly emerged since, where 1.6

billion children and adolescents were affected by the

unprecedented lifestyle changes of the pandemic

(Fegert et al., 2020). Stress, depression, post-

traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and even

suicide rates have dramatically increased all over the

globe (Shi et al., 2021). Additionally, violence,

substance abuse and addictive behaviours were found

to be the effects of COVID-19 related to changes in

lifestyle and isolation (Mengin et al., 2020).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0774-1341

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7110-3718

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5805-4915

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5526-0924

The setting of this study is in the country of

Lebanon. Lebanon has been facing uncertainty due to

the political and economic crises, even before the

onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Diwan and Abi-

Rached, 2020). On February 29th, 2020, a lockdown

was mandated by the education ministry. This left no

time for preparation. The education ecosystem of

curriculum, schools, teachers, parents and students

were unprepared, not ready for the quick transition to

virtual eLearning. Due to the COVID-19 lockdown,

instead of being at school, making social connections

and creating their own personality, adolescents were

confined at home, adapting to new ways to learn.

School closures and social isolation were enough to

subvert adolescents’ daily routine (Chaabane et al.,

2021). Adolescents adapted to texting to socialize

with friends, using social media as a source of

information about COVID-19 infection, and playing

video games during the lockdown. All have

contributed to severe social anxiety (SSA) among

Lebanese adolescents (Itani et al., 2021).

Daibess, N., Badr, N., Yeretzian, J. and Asmar, M.

Consequences of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lebanese Adolescents’ Experience of eLearning: A Call to Action.

DOI: 10.5220/0011538700003335

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2022) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 149-157

ISBN: 978-989-758-614-9; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

149

1.1 Motivation

In general, adolescents are vulnerable to lifestyle

changes, with implications on their physical health

(Fares et al., 2017) and mental health (Younes et al.,

2021). During COVID-19 lockdown, mental

disorders emerged among the Lebanese youth, with

prevalence of psychiatric symptoms related to

insomnia, depression, and anxiety (Younes et al.,

2021). The case of the adolescent population in

Lebanon was alarming. Suicidal intentions appeared

among Lebanese adolescents from 9th to 12th grades

(Chahine et al, 2020). At the time of this research, we

did not find studies covering eLearning impact on

Lebanese adolescents during lockdown. As such, this

paper explores the experience of the Lebanese

adolescent scholars during the Covid-19 lockdown.

So we attempt to answer the following questions:

How did the Lebanese adolescents experience

eLearning during the COVID-19 lockdown?

Moreover, what learnings and call to action can be

presented to improve the experience?

2 BACKGROUND

ELearning, also sometimes referred to as distance

learning, nowadays, is a collection of “educational

processes that utilize information and

communications technology to mediate synchronous

as well as asynchronous learning and teaching

activities” (Jereb and Smitek, 2006). Synchronous

eLearning requires attendance at scheduled meetings

or lectures. The participants can interact with each

other, exchange knowledge and experience, and get

real-time feedback from the audience. Whereas,

asynchronous learning happens when the learner,

teacher, and other participants are not engaged in the

learning process at the same time. They do not benefit

from real-time feedback and interaction, but they are

able to balance different tasks such as school, work,

activities, and family in a way fitting their schedules

(Tsolakidis and Fokides, 2002). Schools’ systems,

worldwide, have shown inconsistent adaptation to

eLearning (Salmi, 2020), while teachers have

developed different approaches and lesson plans

(Commodari and La Rosa, 2021). Among students,

adoption of online platforms for learning has

increased during the pandemic (Dost et al, 2020).

2.1 Lifestyle Disruption and Social

Isolation

ELearning provides flexibility in time and place.

Distance learning provides flexibility for travelling

and the opportunity for self-paced learning; however,

this was relevant to a share of adolescent students

worldwide (Dost et al., 2020). International students

are able to pursue schooling from their own country.

In Malaysia, for instance, two-thirds agreed that

eLearning was flexible in time and place, and one-

third of students felt that eLearning was easy to

understand and use (Ming Moy and Han Ng, 2021).

Another study in Indonesia, reports similar outcome

(Thamri et al., 2022), identifying that comfort-in-

place was conceived as a major advantage of

eLearning during the lockdown. From another

perspective, spending long hours on online platforms

disrupts students’ lives and results in serious

implications on their well-being, but also on their

physical health (Viner et al., 2020). In a sense,

physical neck pain or known as “iHunch” can be

significantly related to prolonged neck flexion while

studying and/or using smartphones and tablets.

Before the pandemic and the wide diffusion of

distance learning, studies showed how facing the

screen for long hours may lead to bad consequences.

Such as, the exposure to cyberbullying, particularly

among adolescents, personal stress and sleep

disturbance, in addition to several mental health

disorders (Sansone and Sansone, 2013). ELearning,

social restrictions, and implications for daily life

related to COVID-19 lockdown have been found to

disrupt sleep habits (Cielo et al., 2021; Viner et al.,

2020), eating pattern among adolescents (Martin-

Rodriguez et al., 2022), who find themselves on

unhealthy eating behaviour, including stress induced

food consumption with no hunger feeling; in addition

to a decreased physical activity.

Students learning from their homes have reported

difficulties in the space available for them to focus on

the lessons away from disruption, such as family

distractions, noise and other activities with their

siblings (Dost et al., 2020). Conversely, others have

reported boredom and anxiety when isolated in a

closed area all day with extreme cases of depression

and suicidal tendencies, due to feeling alone (Mamun

et al., 2020).

Further, unprepared and taken by surprise, low

income countries, Bangladesh and India for instance

(Salmi, 2020), faced serious difficulties related to

Information Technology (IT) infrastructure and

access to internet services, essential to distance

learning. Halfway around the world, Brazil’s 69 state

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

150

university programs were disrupted, while their host

governments scramble to provision solution to extend

such infrastructure (Rios-Campos et al, 2021).

Incidentally, poor internet connection was connected

to increase in anxiety levels of the learners (Dost et

al., 2020) and their ability to perform academically

(Thamri et al., 2022). Sadly, news of like the one of a

15-year old girl awarded “academic brilliance” by her

school, who committed suicide after being unable to

participate in the online classes or watch television

lessons as she did not have a well-functioning

television at home, neither a smartphone, are not rare

cases (Lathabhavan and Griffiths, 2020).

2.2 The Double Edged Sword of

eLearning

While eLearning is shown to be a protective factor in

such health emergencies, researchers found that

undergraduates experienced anxiety, depression,

changes in quality of sleep, and other mental

symptoms due to Covid-19 outbreak (Di Giacomo et

al., 2021). Some students feel that eLearning makes it

easier for them to understand lessons and interact

with teachers and their fellow classmates (Ming Moy

and Han Ng, 2021), others gain technological skills

by using new digital media tools (Hasan and Bao,

2020) facilitating their interaction with their new

virtual environment. Still, however, a significant

population of adolescent learners do not receive

adequate support from their teachers, in this remote

learning setting connected with ineffective

interaction, misunderstandings and

miscomprehension, students could be more

distracted, have difficulty organizing their study

(Commodari and La Rosa, 2021). Due to a lack of

feedback from students, the absence of face-to-face

interaction with teachers may lead to biased

conclusions about academic performance in general

(Eccles and Roeser, 2009). Those who cannot

overcome their bad situations will be at more risk of

having negative emotions, thus mental health

disorders; affecting then their academic performance

(Dost et al., 2020). A stressor event such as academic

stress can generate anger, confusion and depression

(Zhang et al., 2020). Emotional resilience, the ability

to generate positive emotions and recover quickly

from negative emotional experiences is then a coping

mechanism, especially as adolescents are vulnerable

psychologically (Konrad et al., 2013). Having

positive emotions creates emotional resilience

affecting by so the learning efficiency among middle

school students (Zhang et al., 2020).

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

For our qualitative study, we recruited informants

between 10 and 19 years old, Lebanese, living in

Lebanon and registered at one of the Lebanese

schools that adopted e-learning practices during the

Covid-19 lockdown. Nineteen students volunteered

for this study with a median age of 14 (Table 1). We

purposefully selected two private schools one in

Saida and one in Beirut administrative for they have

different socio-economic status (Yaacoub and Badre,

2012; LRCAS, 2020). We used a voluntary response

sampling to gather quality and dependable research

data (Murairwa, 2015). Data collection was

completed until saturation; adopting semi-structured

interviews with open-ended questions. Interviews

were private, lasting between 12 and 20 min. each,

over a span of three days March, 5th, 2022; May 7th,

2022; and May 30th, 2022; after a period of two

academic years of the COVID-19 lockdown.

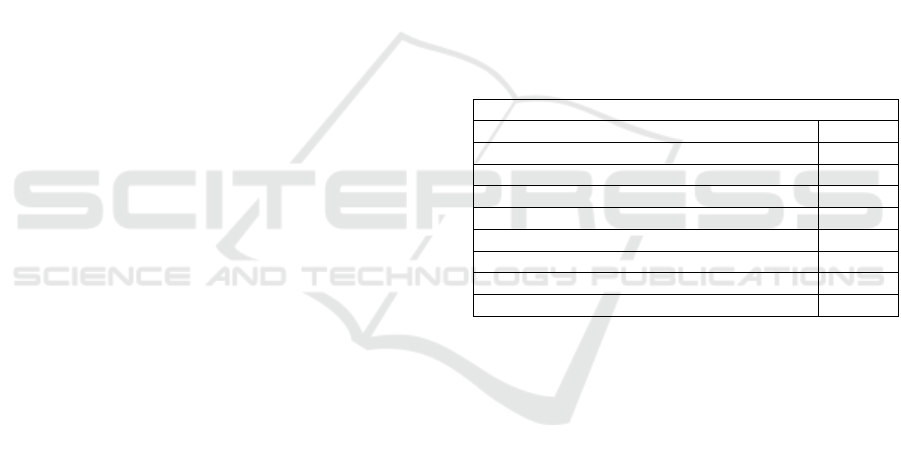

Table 1: Our Student Sample profile.

Sam

p

le Profile (n=19)

Avera

g

e A

g

e13

Median Age 14

Female 8

Male 11

Grade 1

–

6

(

Elementar

y

- A

g

es 6

–

12

)

* 32%

Grade 7

–

9

(

Intermediate - A

g

es 12

–

15

)

* 42%

Grade 10

–

12 (Secondary Ages 15-18)* 26%

School A 32%

School B 68%

*

https://www.scholaro.com/pro/Countries/Lebanon/Education-

System

School A: Saint-Joseph school - Saida

School B: Our Lady College of Angels- Beirut administrative

We then coded the response to identify emerging

categories, themes and patterns. We used themes

from section 2; themes of (1) lifestyle disruption; (2)

Depression, anxiety and stress; and (3) coping with

eLearning stressor events (Appendix C). We

uncovered reports of lifestyle disruption, namely,

reduced activity, studying in unfavourable

environments, the impactful effects of isolation and

changes in appetite and sleep. We also learned about

anxiety and depressive tendencies, stress indicators

and the consequent coping mechanisms, as we

explain in section 4. We finally organize the concepts

into a call to action for a better adolescent eLearning

experience, in section 5.

Consequences of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lebanese Adolescents’ Experience of eLearning: A Call to Action

151

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Students participating in this study appreciated

learning from their own place, at first. They perceived

at-home-comfort as a major advantage of eLearning

during the lockdown. The flexibility and extra time

that is not spent commuting to and from school,

opened an opportunity for them to pursue

extracurricular activities online; “In my spare time, I

was studying online, and also doing something I love,

like painting, watching videos about space, etc.”

[S#3]. As the lockdown extended, and reality set in.

“The limitation on outdoor activities drove me stir

crazy”, shared Student #6. “I don’t have sisters or

brothers. It was boring”, said S#9 with a saddened

voice.

4.1 Lifestyle Disruption

Our study reports that students staying alone, in their

place, during the whole hours of learning, makes

them uneasy, and uncomfortable. When trying to

change their sitting, they face difficulties because of

the noisy environment, internet connection issues,

and undesirable settings (Dost et al., 2020); especially

if they want to take notes [S#5].

Spending long hours facing the screen disrupts

students’ life (Viner et al., 2020). S#1 was “stifled

during online classes. From 9AM till 2PM, daily, in

the same place, on that chair without moving”. Our

findings are consistent with Viner et al. findings.

“Staying in a room for that long, really changes us”

[S#5]. “It’s like nothing. I study, take a shower,

dinner, sleep”, he adds. “It is a waste of time” [S#6].

Eating patterns in general, have also been

disturbed among adolescents during COVID-19

lockdown, leading to unhealthy diet and a decreased

physical activity (Martin-Rodriguez et al., 2022).

Students experienced variations in their weight and

appetite despite their cravings all the day. Cravings

were due to several reasons. Among them all, late

hour sleep at night, easy access to kitchen, no place to

go to, boredom, frequent use of smartphones, and

online classes. Student#11, mentioned that he ate less

because of the high cost of food.

The experience affected students’ wellbeing,

making them lazy, feeling bodily spasms [S#5],

lonely and fatigued [S#6], depressed [S#9] and bored

[S#12; #17]. During online classes, all students

reported bad virtual interaction, leading them to lose

focus [S#18] during sessions. “I remember when the

teacher called on us, no one answered. As if she was

speaking to herself. I wanted to answer, but I was not

feeling okay. I was lazy to answer”, said S#6.

One student had reversed the daily sleep cycle to

meet her new schedule. “My classes were in the

afternoon, I was sleeping late at 2 AM or 4 AM and

wake up at 2 PM, I was skipping breakfast, sometimes

lunch, so I wait for my parents to have my dinner” [S#

9]. This finding echoes the study of Cielo et al.

(2021), showing that changes in sleep habits of

adolescent scholars are the results of several stressors.

Among them, massive eLearning, social restrictions,

and implications for daily life related to COVID-19

lockdown (Viner et al., 2020).

To complicate matters, Lebanon has been under

shortage of electric power, due to the existing

economic crisis. All students complained from

electric power disruption and internet connection

issues during online classes. Consequently, missing

basic information and misunderstanding the lessons.

“I get disconnected often and I have to re-watch the

recordings to understand what I have missed”, a few

students exclaimed. “I sometimes look the lesson

material up on YouTube, so to better understand the

concepts”, stated another. Those who had internet

connection issues feared that teachers would reduce

their grades. Teachers were often late to start the

session as they also had to deal with interrupted

power and internet. When online, the connection

would be intermittent, “adding distortion to the

lecture and making it hard to follow” [S#12]. “At

school, we understand better. We can hear well” [S

#16]. Our findings are consistent with the literature,

especially in the context of developing countries,

where such challenges are more commonly observed

(Dost et al., 2020; Thamri et al., 2022).

4.2 Depression, Anxiety and Stress

One student’s words: “I was trying not to end up

here, but I felt depressed. I was feeling like there is

nothing to do in life, locked in a place. I was not

used to it. I tried many times to overcome it. What

really helped me was songs. I was fearing to show

my anxiety to my friends, or open social media. They

will bully those who are depressed. But I became

more active on tiktok”.

High prevalence of stress, depression and low-

self-confidence are perceived as results of massive

eLearning adoption, and social isolation. Some of the

participants reported bad organization of their tasks,

leading to accumulation of their studies and confusion

in their lesson plans. “There are many activities and

homework that accumulate from course to course and

scattered materials” [S#1] – “I am finding myself

studying all the time and not keeping up” [S#6].

Another student exclaimed in frustration: “I was

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

152

cheating during exams, because of my lack of

understanding. I was not understanding well”.

One student has reported having depression when

listening to her teacher’s monotonous voice. Others

complained of teachers’ attitudes during their online

classes, feeding into their stress and anxiety. “I was

feeling stress because of the teacher’s voice and

attitude when she asks me questions in front of the

class. Also when reciting, all microphones are muted,

I cannot sense their reaction” [S#11].

Students saw that some of the teachers were not

explaining well, unexperienced in digital platforms

and not following-up with students as needed. “I was

getting depressed. Studying was no longer my top

priority. I was sleeping all day, and I lost interest in

studying” [S#15]. In this case, our study lines up with

the findings of (Commodari and La Rosa, 2021).

Luckily, no suicidal intention was reported by

students. However, our informants stated that they

have experienced anxiety and loss of self-esteem,

because they were afraid of bullying. The main

mental health issues felt by participants in this study

were stress, depression and anxiety. The main reasons

of those psychological problems were: fear of bad

failure [S#5], daily routine [S#1], exam anxiety [S#7;

#10], and stressful frustrations with internet

connection issues [S#6] “to the extent of suffering

from insomnia, or sweating, or even tachycardia!”

[S#3].

4.3 Coping with eLearning Stressors

Some students exhibited low self-confidence due to

the misunderstanding of lessons, leading them to

cheat during exams. However, only one person

reported having high confidence, for she was using

Tiktok. The application was giving her a sense of

motivation [S#13]. Social isolation has driven

students#5, 6, 7, 11, 19 to feel depressed and wanted

to deal with it slightly, in fear of societal judgement.

Nonetheless, to cope and motivate themselves, some

rushed to social media, others started listening to

music, practicing yoga and meditation, painting, and

receiving psychological support from their families.

To note, positive emotions, and coping strategies are

known to be essential for learning efficiency among

students (Zhang et al., 2020). Knowing that, students

who cannot overcome their bad situations will be at

more risk of having negative emotions, thus mental

health disorders; affecting then their academic

performance. While the majority of the adolescent

students liked the comfort of studying in a warm bed

in the morning, staying in pyjamas all day [S#9], and

the opportunity to slack off, sleeping during classes,

cheat in exams, two stood out stating that “online

learning has brought in them the sense of

responsibility [S#12].

All in all, students preferred a traditional school

setting – some expressed no interest in continuing

such online experience and others saw that the online

experience saved their academic year.

When asked about their input as opportunities for

improvement of the online experience – some stated

the desire for a better connection experience (Power

and Internet) – ensuring continuous access to

resources through resilient communication platforms.

Others suggested more opportunities for teacher-

student interaction exercises of blended learning,

specifically designed for the adolescent audience –

such as subjects of discussion that are more

interactive to spar a debate and liven the sessions.

A student came forth with the recommendation to

make psychologist services available for students -

“maybe having access to a psychologist once a week

for one hour could help” [S#12].

A suggestion of hybrid, in-school-at-home

modality for teaching was popular; “we can go at

least one day per week to school; like, we can go

every two days”.

To improve their experience, students recorded

their lessons. A suggestion of hybrid, in-school-at-

home modality for teaching was a popular ask with a

clear expression of need for teachers who are more

adept in using technology tools. Students suggested

that teachers should be trained on manipulating

technology and digital devices, while having more

follow-up with students and maybe including 3D

technology tools “to see our teacher in front of us”

[S#17]; to improve the experience - “better to study

with hologram, to see our teacher, like in a virtual

reality school”. Great ideas of innovation in using

holographic teachers to closely simulate the real

experience, in addition to online content delivery,

mobile apps for building awareness and multimedia

tools to enable captive interaction and reduce feelings

of isolation.

Parents of our informants also offered suggestions

for opportunities to get closer to the interaction

between teacher and student with the opportunity to

lessen the burden on the teachers and student and

improve the distant learning experience. A parent,

who was present at the interview of a student,

suggested a more rigorous parent teacher conference

during such conditions so that parents could closely

supervise the academic progress of their adolescent

kid. Another parent, a student’s mom, stated that they

are supplementing the schooling with a private at

Consequences of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lebanese Adolescents’ Experience of eLearning: A Call to Action

153

home teacher as she lost confidence in the efficacy of

eLearning.

5 CONCLUSION

This study shows how Lebanon was grappling with

an education emergency. Our empirical inquiry has

identified depressive tendencies, stress and anxiety

indicators in the respondents remarks. Unable to

become interested or involved, worrying about

performance and possible loss of control and

intolerance of interruption or delay, are high scorers

in the DASS-21 scales, assessing Depression,

Anxiety and Stress conditions (Osman et al, 2012).

One of the main risk factors for depression during the

pandemic is disruption of physical activity (Giuntella

et al., 2021). Our findings have uncovered significant

effects of isolation, lack of activity, while having to

accommodate to an unfavourable study environment.

In these trying times, our adolescent student

population have joined other university students

(Fawaz and Samaha, 2021) who were eLearning

during the pandemic in Lebanon. Due to the stressful

workload required, students have developed anxiety

and depression symptoms as a result of the abrupt

shift to exclusive eLearning methods of instruction,

notwithstanding issues raised by risks to privacy,

cyberbullying, and the increased appetite for

plagiarism (Alier, 2021).

In order to curb the effect of this emergency and

the potential of more damage in future ones,

researchers, stakeholders, public health workers, and

educational institutions must set in motion plans for

improving educational strategies, setting a

preparedness emergency plans for eLearning.

5.1 Call to Action

Knowledge that has been acquired from this small

sample could be informative under the theory of

knowledge to action (Graham and Tetroe, 2010). We

have identified the thematic problem of

disengagement and, from the outcome of the study,

provide a call to action to remedy this situation for the

future. Students have exhibited some evidence for

lessons learned in the diversification of learning

modality, content, self-motivation, gamification,

suggestion to how teachers ought to be trained on

managing the knowledge delivery during such

disruptive change, introduced by the pandemic.

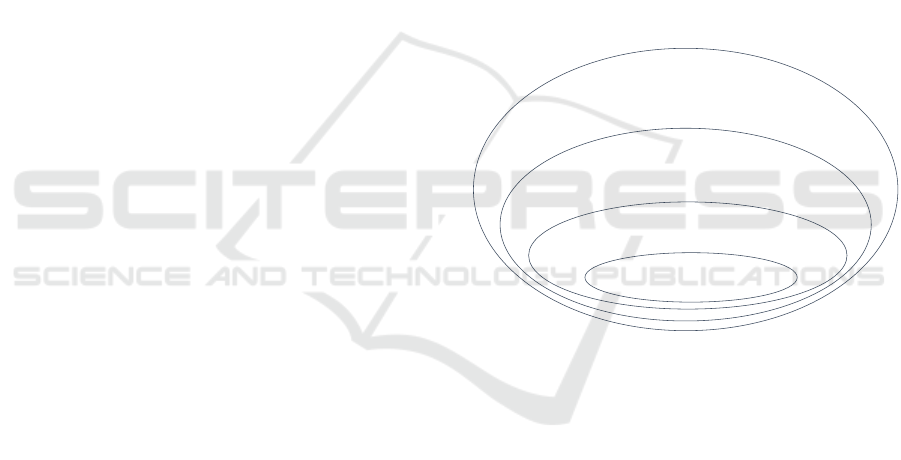

We use the socio-ecological model of

Bronfenbrenner (1977) to organize some insights

from our work and promote the development of the

human condition in a changing eLearning

environment conceived around an ecosystem of

individual, community, organizational and policy

making (Figure 1).

At the individual level, a creation of a healthy

lifestyle program during a health emergency, is a

must. Each member of society should be aware of

their risks and prevention steps to take with coping

mechanisms to apply so to relieve the consequences

of a pandemic on their daily life. Students would have

resources available to them to use to organize their

day, by prioritizing their tasks, eating healthy,

sleeping well, avoiding bad behaviours and also

providing them with healthy diet plans regarding

students’ weight, height and health problems, if any.

Schools should be always in close contact with

teachers and students ensuring a healthy delivery of

information that will be used for ever at any time. In

doing so, eliminating many potential unsatisfactory

consequences.

Figure 1: Call to Action for a better adolescent eLearning

experience, adapted from Bronfenbrenner (1977).

Further, our work has revealed that parents have

an integral role in the improvement of the eLearning

experience – they must be encouraged to do so in

closer supervision of the interaction between teacher

and student, at the community level.

At the organizational level, schools should be

elaborating an educational preparedness plan for such

health emergencies to be implemented timely and

appropriately. Schools must develop opportunities for

teacher-student interaction through exercises in

blended learning designed for the adolescent, lesson

plans designed to liven the sessions, potentially

through innovations in 3D technology and

gamification. Further, to preserve adolescents’

mental health, schools should provide regular mental

health assessment not only for their students, but also

for their teachers and staff, aiming to prevent,

diagnose, and treat any mental health disorder. Thus,

Enabling

Enviro n m ent

Organizational

Community

Individual

Improve digital literacy of teachers;

Ensure access to communication resources;

Legislation, standards and financing mechanisms

Educational preparedness plan;

Improve teacher-student interaction;

Mental health support for students and teachers

Oversight role of parents in hybrid learning experiences

Healthy lifestyle awareness program;

Coping mechanisms

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

154

reducing the risk of potential mental health

repercussions on the physical health of individuals.

Priority should be given to investing in

technological equipment in schools for the majority

of students, as well as training teachers in digital

competence. Educational institutions in collaboration

with ministry of education should provide teachers

with more intensive courses related to digital

technology to help teachers modify their way of

teaching and make it better; by improving their

technological skills, academic acuity and adaptability

(Hennessy et al., 2021). Private agencies, public

service providers must ensure access to

communication resources such as power and

telecommunications, to ensure the continuity of the

experience, while policy makers must legislate

around standards and financing mechanisms for

successful implementation.

5.2 Contribution and Limitations

Our work is informative, to confirm that Lebanon’s

adolescents are no different to adolescents all over the

world in how they have responded to COVID-19.

Some have learnt from the experience, but the overall

impact was quite disruptive, our informants

disengaged from the learning process, however, many

provided good insight into improvement, especially

in societies living with low social economic status.

We plan to improve on this study via a triangulated

statistical analysis in the near future.

We suggest that further research would explore

further on complementary contexts of this study, so

to address some of the natural limitations in scope and

breadth of this study as public school students were

not represented in this scope and the sample size was

restricted to two private schools. Still however, our

paper is a strong seminal work and the sample size is

adequate for this successful pilot (Isaacs, 2014) that

will undoubtedly spark an interest for further

discoveries.

In closing, this study provides some useful advice

to lesson planners on how to improve the experience.

First, by limiting potential academic disruption if the

course modality unexpectedly shifts and providing

students with course materials in efficient and

accessible ways, potentially gamified by the use of

3D holographic technology, or online videos to

supplement the coursework. Students expressed the

necessity for more flexibility, control, and options

regarding when and how they learn. Allowing faculty

to engage in the process of building their courses over

time, was also key in the ability to transition modality

in course delivery for effective participation.

REFERENCES

Alier, M. (2021). Information Systems, E-Learning and

Knowledge Management (in the Times of COVID).

Sustainability, 13(19), 10674.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental

ecology of human development. Am Psychol, 32:513–

531.

Chaabane, S., Doraiswamy, S., Chaabna, K., Mamtani, R.,

& Cheema, S. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 School

Closure on Child and Adolescent Health: A Rapid

Systematic Review. Children (Basel, Switzerland),

8(5), 415.

Chahine, M., Salameh, P., Haddad, C., Sacre, H., Soufia,

M., Akel, M., Obeid, S., Hallit, R., & Hallit, S. (2020).

Suicidal ideation among Lebanese adolescents: scale

validation, prevalence and correlates. BMC Psychiatry

(20), 304.

Cielo, F., Ulberg, R., & Di Giacomo, D. (2021).

Psychological impact of the covid outbreak on mental

health outcomes among youth: a rapid narrative review.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 18, 6067.

Commodari, E., La Rosa, V.L. (2021). Adolescents and

distance learning during the first wave of the COVID-

19 pandemic in Italy: what impact on students ‘well-

being and learning processes and what future

prospects? Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ., 11,

726–735.

Di Giacomo, D., Martelli, A., Guerra, F., Cielo, F. &

Ranieri, J. (2021). Mediator effect of affinity for e-

Learning on mental health: buffering strategy for the

resilience of university students. Int. J. Environ. Res.

Public Health (18), 7098.

Diwan, I., &Abi-Rached, J. M. (2020, April). Killer

lockdowns. In Economic Research Forum Policy Portal

(Vol. 21).

Dost, S., Hossain, A., Shehab, M., Adbelwahed, A., Al-

Nusair, L. (2020). Perceptions of medical students

towards online teaching during the covid-19 pandemic:

a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 uk medical

students. BMJ Open.

Eccles, J.S.; Roeser, R.W. Schools, Academic Motivation,

and Stage-Environment Fit. In Handbook of Adolescent

Psychology; Lerner, R., Steinberg, L., Eds.; Wiley:

New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 404–434.

Fares, J., Fares, M., &Youssef, F. (2017). Musculoskeletal

neck pain in children and adolescents: risk factors and

complications. Surgical Neurology International (8),

72.

Fawaz, M., & Samaha, A. (2021, January). E‐learning:

Depression, anxiety, and stress symptomatology among

Lebanese university students during COVID‐19

quarantine. In Nursing forum (Vol. 56, No. 1, pp. 52-

57).

Fegert, J., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. & Clemens, V. (2020).

Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (covid-

19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a

narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs

in the acute phase and the long return to normality.

Child Adolescent Psychiatry Mental Health, 14,20

Consequences of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lebanese Adolescents’ Experience of eLearning: A Call to Action

155

Giuntella, O., Hyde, K., Saccardo, S., & Sadoff, S. (2021).

Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-

19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

118(9), e2016632118.

Graham, I. D., & Tetroe, J. M. (2010). The knowledge to

action framework. Models and frameworks for

implementing evidence-based practice: Linking

evidence to action, 207, 222.

Hasan, N. & Bao, Y. (2020). Impact of “e-Learning crack-

up” perception on psychological distress among college

students during covid-19 pandemic: a mediating role of

“fear of academic year loss”. Children Youth Services

Review.

Hennessy, S., D’Angelo, S., McIntyre, N., Koomar, S.,

Kreimeia, A., Cao, L., ... & Zubairi, A. (2021).

Technology, teacher professional development and

low-and middle-income countries: technical report on

systematic mapping review.

Isaacs, A. (2014). An overview of qualitative research

methodology for public health researchers.

International Journal of Medicine and Public Health, 4

(4).

Itani, M., Eltannir, E., Tinawi, H., Daher, D., Eltannir, A.

& Moukarzel, A. (2021). Severe social anxiety among

adolescents during covid-19 lockdown. Journal of

Patient Experience, (8)1–10.

Jereb, E., & Šmitek, B. (2006). Applying multimedia

instruction in e‐learning. Innovations in Education and

Teaching International, 43(1), 15-27.

Konrad K., Firk, C. & Uhlhaas, P. (2013). Brain

development during adolescence: neuroscientific

insights into this developmental period. Deutsches

Ärzteblatt International, 110 (25): 425–31.

Lathabhavan, R., & Griffiths, M. (2020). First case of

student suicide in India due to the COVID-19 education

crisis: A brief report and preventive measures. Asian

journal of psychiatry, 53, 102202.

LRCAS, 2020. Labor Force and Household Living

Conditions Survey 2018-2019 in Saida. Lebanese

Republic Central Administration of Statistics. (2020).

Mamun, M., Chandrima, R., & Griffiths, M. (2020). Mother

and son suicide pact due to covid-19-related online

learning issues in Bangladesh: an unusual case report.

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction.

Martín-Rodríguez, A., Tornero-Aguilera, J.F., López-

Pérez, P.J., Clemente-Suárez, V.J. (2022). Dietary

patterns of adolescent students during the COVID-19

pandemic lockdown. Physiol Behav.

Mengin, A., Allé, C., Rolling, J., Ligier, F., Schroder, C.,

Lalanne, L., Berna, F., Jardri, R., Vaiva, G., Geoffroy,

A., Brunault, P., Thibaut, F., Chevance, A., Giersch, A.

(2020). Psychological consequences of confinement.

L’Encéphale, 46 (3), S43-S52.

Ming Moy, F., Han Ng, Y. (2021). Perception towards e-

learning and covid-19 on the mental health status of

university students in Malaysia. Science Progress,

104(3), 1–18.

Murairwa, S. (2015). Voluntary sampling design.

International Journal of Advanced Research in

Management and Social Sciences, 4(2), 185-200.

Osman, A., Wong, J. L., Bagge, C. L., Freedenthal, S.,

Gutierrez, P. M., & Lozano, G. (2012). The depression

anxiety stress Scales—21 (DASS‐21): further

examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and

correlates. Journal of clinical psychology, 68(12),

1322-1338.

Rios-Campos, C., Macias, P. M. T., González, J. E. R.,

Araujo, M. R. Q., Tirado, W. C. G., Castro, M. Á. V.,

... & Herrera, D. S. (2021). Brazilian Universities–

Problems, COVID-19 & Efforts: Universidades

Brasileñas–Problemas, COVID-19 y Esfuerzos. South

Florida Journal of Development, 2(4), 5838-5850.

Salmi, J. (2020). COVID’s lessons for global higher

education.

Sansone R. & Sansone, L. (2013). Cell phones : the

psychosocial risks. Innov Clin Neurosci.,10, 33–7

Shi, L., Que1, Y., Lu1, A., Gong, M., Liu, L., Wang, H.,

Ran, SH., Ravindran, N., Ravindran, V., Fazel, S., Bao,

P., Shi, J., & Lu, L. (2021). Prevalence and correlates

of suicidal ideation among the general population in

china during the covid-19 pandemic. European

Psychiatry, 64 (1), 1-10.

Thamri, T., Chitra Hasan, D., Rina, N., Hariri Gani, M.,

Hariri Gani, M., & Maharani Miranda, A. (2022).

Advantages and disadvantages of online learning

during the covid-19 pandemic: The perceptions of

students at Bung Hatta University. KnE Social

Sciences, 7(6), 329–338.

Tsolakidis C. & Fokides, M. (2002). Distance education:

synchronous and asynchronous methods. A

comparative presentation and analysis in proceedings

"Interactive Computer Aided Learning, ICL”.

Σεπτεμβρίου, Carinthia Tech Institute, Kassel

University Press, 25-27, ISBN 3-933146-83-6-2002

Viner, R., Russell, S., Croker, H., Packer, J., Ward, J.,

Stansfield, C., et al. (2020). School closure and

management practices during coronavirus outbreaks

including covid-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet

Child Adolesc Health., 4, 397–404.

Yaacoub, N. & Badre, L. (2012). Population and housing in

Lebanon. Central Administration of Statistics (2).

Younes, S., Safwan, J., Rahal, M., Hammoudi, D., Akiki,

Z., & Akel, M. (2021). Effect of covid-19 on mental

health among the young population in Lebanon.

Encéphale.

Zhang, Q., Zhou, L., & Xia, J. (2020). Impact of covid-19

on emotional resilience and learning management of

middle school students. Medical Science Monitor.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

156

APPENDIX

A Participant Information

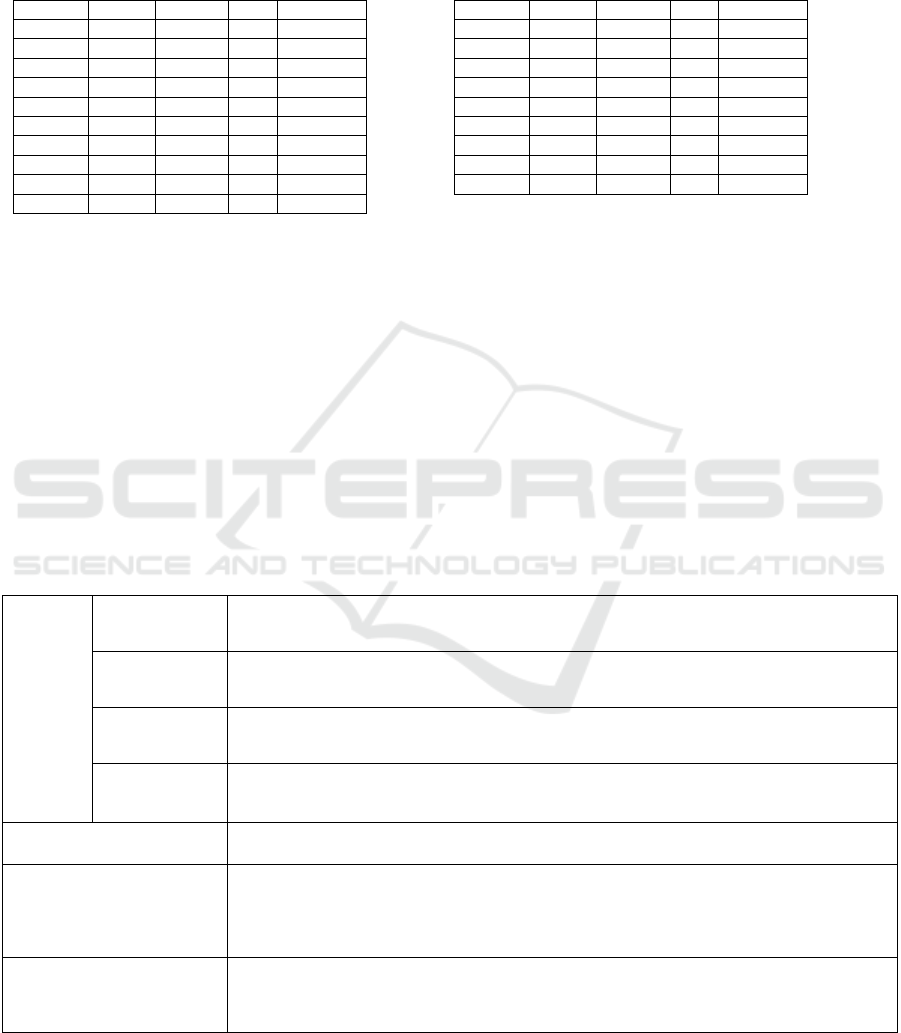

Table 2: Participants Profile.

Student School Gender Age Grade

S#1 A Female 15 10 (Bac.1)

S#2 A Female 13 9

S#3 A Female 14 9

S#4 A Male 15 9

S#5 A Male 11 5

S#6 A Female 14 9

S#7 B Male 16 10 (Bac.1)

S#8 B Female 16 11 (Bac.2)

S#9 B Female 14 8

S#10 B Male 11 6

Student School Gender Age Grade

S#11 B Male 12 6

S#12 B Male 18 12 (Bac.3)

S#13 B Female 18 12 (Bac.3)

S#14 B Female 12 7

S#15 B Male 14 9

S#16 B Male 11 6

S#17 B Male 12 7

S#18 B Male 11 6

S#19 B Male 11 6

B Questionaire

1. Tell me about yourself (age/place of residence)

2. Do you love to study?

3. Tell me about what was entices you to go to school everyday

4. Tell me about your relationship with your teachers and schoolmates.

5. Do you find school demanding?

6. Tell me about what you did during the lockdown. Have you changed your daily lifestyle?

7. Do you think that eLearning made your life easier when it comes to studying?

8. Do you think distance learning is easy?

9. What challenges did you face?

10. How did you feel during the lockdown? How did you overcome the situation?

11. How do you think we can improve distance learning in Lebanon?

C Coding Results

Table 3: Consequences of eLearning in Pandemic times with samples from the student interviews (Partial Illustrative Sample).

Lifestyle

Disruptio

n

Reduced activity “The limitation on outdoor activities drove me stir crazy” [S#6]; “…stifled during online classes. From

9AM till 2PM, daily, in the same place, on that chair without moving” [S#1]; “It’s like nothing. I

study, take a shower, dinner, sleep” [S#5]; “… It is a waste of time”[S#6].

Unfavourable

environment

Noisy environment, internet connection issues, and undesirable settings especially if they want to take

notes. [S#5]; “I get disconnected often, adding distortion to the lecture and making it hard to follow”

[S#12]

Effect of

isolation

The experience affected the students’ wellbeing, making them lazy, feeling bodily spasms. “I don’t

have sisters or brothers. It was boring” [S#9]; “Staying in a room for that long, really changes us”

[S#5]

Change in Habits

(Eat / and Sleep)

“My classes were in the afternoon, I was sleeping late at 2 AM or 4 AM and wake up at 2 PM, I was

skipping breakfast, sometimes lunch, so I wait for my parents to have my dinner” [S#9]. “Stifled during

online classes. From 9AM till 2PM, daily, in the same place, on that chair without moving” [S#1];

Anxiety

Feared that teachers would reduce their grades; “to the extent of suffering from insomnia, or sweating,

or even tachycardia!” [S#3]; “I am finding myself studying all the time and not keeping up” [S#6].

Depressive tendencies

Lonely and fatigued [S#6]; depressed [S#9]; bored [S#12; #17]; lose focus [S#18] during sessions; “I

was trying not to end up here, but I felt depressed. I was feeling like there is nothing to do in life,

locked in a place…. [S#8]”; “There are many activities and homework that accumulate from course to

course and scattered materials” [S#1]; “I was getting depressed, studying was no longer my top

priority, I was sleeping all day and lost interest in studying” [S#15].

Stress indicators

“I was cheating during exams, because I was not understanding well!”; “I was feeling stress because

of the teacher’s voice and attitude when she asks me questions in front of the class…” [S#11]. “When

the teacher called on us, no one answered. As if she was speaking to herself. I wanted to answer, but I

was not feeling okay. I was lazy to answer”[S#6]

Consequences of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lebanese Adolescents’ Experience of eLearning: A Call to Action

157