Knowledge Management and Benchmarking for Health Care System

Development Activities

Annamaija Paunu, Hannele Väyrynen and Nina Helander

Information and Knowledge Management, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Benchmarking, Healthcare, Case Study.

Abstract: Knowledge management (KM) has a central role in developing health care services both at the organization

and at the system level. Benchmarking can be used as a tool in KM especially for knowledge creation and

acquisition, but also for knowledge sharing phases of KM process. In the end, the value created by

benchmarking is still measured in the knowledge utilization phase. In all of these KM process phases there

can be several challenges for successful benchmarking. In this paper, the benefits and challenges of

benchmarking as a tool for KM is studied through two empirical, qualitative case studies from the Finnish

health care system. Empirical findings suggest that more effective benchmarking can be achieved by

strengthening strategy orientation and systematic approach. Strategy-driven benchmark practices ensure that

benchmarking is targeted correctly. In turn, systematic approach can be increased through well-planned

knowledge acquisition, sharing and documentation, and by harnessing operations in networks as a goal-

oriented part of the development of the health care organizations’ competencies and operations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Health care systems are one of the most critical

systems in societies (Keskimäki et al. 2019) and are a

solid foundation for the daily life of citizens.

Especially in the midst of crises, such as the COVID-

19 pandemics or wars which cause massive effects

around the world, resilience is required from

healthcare systems. The resilience of the health care

system can be seen in how quickly and at what

capacity health care can produce and provide health

care services to the entire community in the event of

a shock. (Lo Sardo et al., 2019) Knowledge

management (KM) has been identified as one of the

key factors in developing resilience (see e.g. Irfan et

al. 2022; Mafabi et al., 2013). The cornestones of KM

for development activities according to the work by

Sharma et al. (2013) can be listed as knowledge

creation; knowledge transfer and diffusion, and

knowledge utilisation and exploitation. As Sharma et

al. (2013) have stated, in many cases KM for

development activities requires benchmarks.

Benchmarking enables the process of acquiring and

transforming explicit and tacit knowledge (Massa &

Testa, 2004), which plays a central role in classic KM

models (Nonaka, 1994).

Benchmarking can be defined as the comparison

of strategies or processes within different industries;

finding best practices or benchmark can enhance

learning in the organisation (Grayson, 1992; Watson,

1994). Furthermore, benchmarking can prevent

unjustified complacency in an organisation, relying

on your own knowledge too much, for example

(Zairi, 1994) and it can also enhance problem solving

(Andersen and Moen, 1999). Thus it is no surprise

that an increasing need for benchmarking has been

identified in the public sector too (Raymond, 2008;

Hong et al., 2012). To succeed, benchmarking needs

management support, as a strategy-based

benchmarking process needs to be planned, organised

and managed besides requiring, understanding of the

organisation´s own processes before benchmarking

(Grayson, 1992). However, best practices are not

always transferable but may need modifications

because of the cultural context or sectoral legislation

(Watson, 1994).

Municipalities, including cities, often play a key

role in developing healthcare in societies. Thus, they

have huge responsibilities and face many challenges

in their development activities in the healthcare

context. In this paper, we aim to identify the benefits

and challenges of benchmarking in two cases from

Finland: a city organization involved in organizing

Paunu, A., Väyrynen, H. and Helander, N.

Knowledge Management and Benchmarking for Health Care System Development Activities.

DOI: 10.5220/0011540800003335

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2022) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 163-168

ISBN: 978-989-758-614-9; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

163

health care services and a Wellbeing services county

of Pirkanmaa.

The remain of the paper is organized as following.

Theoretical bases of benchmarking is first introduced.

Research method and the case organizations are then

briefly introduced and followed by the description of

the key results of the empirical study. The paper is

finalized by the conclusions and discussion section.

2 BENCHMARKING PROCESS

The benchmark process consists of many sources of

information, various actors and step-by-step phases of

different tasks. Benchmarking can target the

individual or team level, organizational level, urban,

regional or national level. (Spendolini, 1992) For

example, a single comparison can be made at city

level, with the aim of finding out how the city ranks

on a specific theme in a global-level comparison.

Another identifiable target could be the comparison

of the best practices regarding a product or process.

(Wolfram Cox et al., 1997) The tools of the

benchmarking process that are selected are also

influenced by whether the benchmarking is being

carried out to compare the organisation's own

practices or learning (Braadbaart and Yusnandarshah,

2008), strategy-level planning, strategic choices or

implementations (Chase, 1997), or to compare the

performance of the organisation against other

organisations (Kim and Lee, 2010). This paper

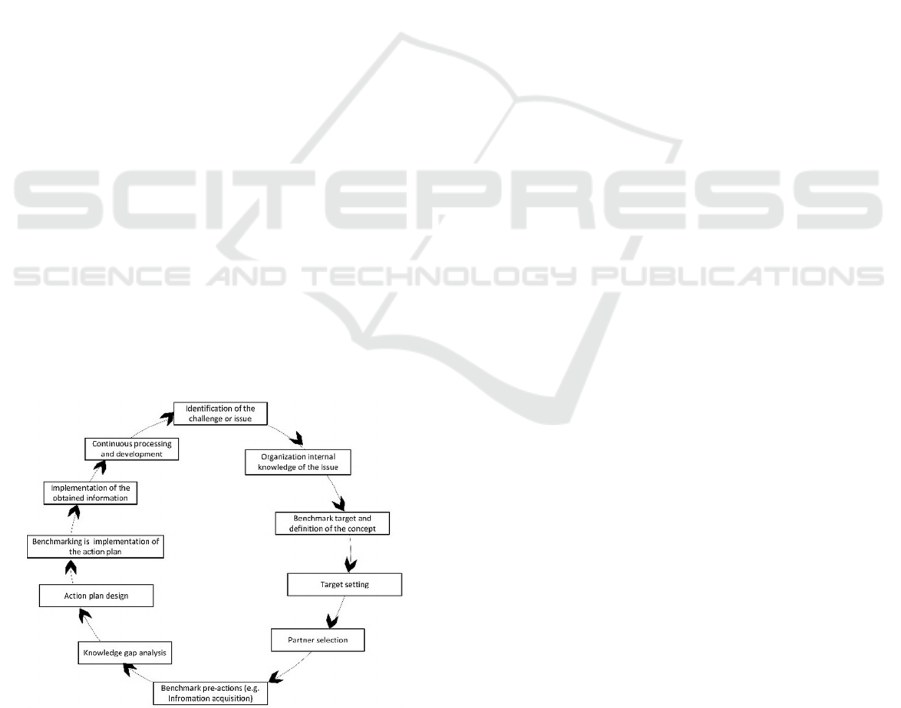

considers benchmarking through Anand and Kodali´s

benchmarking model (2008). The modified steps of

the benchmarking actions are introduced in Figure 1

below.

Figure 1: Benchmarking process steps (modified from

Anand and Kodali, 2008).

The benchmarking process begins by identifying the

topic, i.e. what kind of new and comparable

information is needed. There will be a lot of internal

tacit knowledge in the organisation, and it is worth

finding out about the organisation´s own knowledge

and expertise in the topic.

A more accurate definition of the benchmark is an

important step. Framing a topic with a specific

concept helps the benchmarkerkers in the data

acquisition process (e.g., Francis and Holloway,

2007). The point of comparison in the benchmarking

should also be limited, for example, regional

delimitation would targets the data acquisition source

material more precisely.

The setting of a target is important in order to

clarify the idea of the benchmarking objectives and to

have a common understanding of what one wants to

achieve (Watson, 1994). Target setting is also

important for assessing subsequently whether the

desired information was obtained and whether the

objectives set by the benchmarking were achieved.

Choosing a partner means, selecting a partner to

carry out the process itself or other collaborators.

Knowledge at the network level is multidimensional;,

partners share industry specific knowledge with

members of the network, as well as the organisation’s

internal knowledge (Sammarra and Biggiero, 2008)

Therefore, shared resources in implementation guide

the benhmarkers to focus on their own use of know-

how in the process itself. For example, external

organisations or research institutions may offer their

services to support the partial implementation (e.g.

literature review, interviews, etc.) or the process

implementation as a whole.

Before the actual visit the benchmarking terget, to

another city or country, benchmarking pre-work

includes the information acquisition process. There

are different search portals or databases for searching

for and analysing targeted information about

products, services or processes, e.g. case studies,

specific themes, cities or organisations that have been

made earlier (Castro and Frazzon, 2017). It is worth

formulating a few relevant benchmark questions with

the team is good to formulate in order to reflect on

and find answers to the benchmarking challenge or

issue in advance. Based on the benchmarking

material already found, a data gap analysis will reveal

what has already been studied on a particular topic

(and where).

The development of the benchmarking plan will

help to focus on the essential in the information

search: objectives for the benchmarking and how to

implement the benchmarking (e.g. visit, online

meeting, consultancy or database-based survey). It is

also a good idea to include, for example, the intended

contact persons, the scheduling of operations and the

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

164

persons responsible for the different stages in the

process itself (Watson, 1994).

The benchmarking process also includes the

implementation of the action plan (Shiem-Shin Then,

1996), which needs to be flexible. For example, the

original contact persons may change to another

person who uses their own networks to lead the

process perhaps in a different direction than planned.

Otherwise, in this phase it is essential to keep in mind

the objectives of the benchmarking and the

benchmark questions, to which answers are being

sought. If a large group participates in a visit or

network meeting, sharing the research questions

among the group members will help to focus on

capturing the most relevant information from the

discussions. The obtained information can be

documented later.

The obtained benchmark information needs a

implementation plan as well (as part of the action

plan); what and how the information is to be shared

with a wider range of organisations, what information

is to be shared publicly, how the results can be

documented easily and quickly, and how to

implement the obtained experience in the

organisation's activities or whether pilots are to be

carried out (Feizabadi et al., 2019). After these

questions, the organisation will evaluate what was

learnt in the benchmarking process, and share the

lessons learned more widely with the public.

Simultaneously, the final stage of the benchmarking

process, continuous processing and the development

phase, will lead the organisation to consider how the

data on different issues can be utilised and how the

experiences gained from the compared objects can be

implemented in its own operations, strategic planning

or decision-making processes.

3 RESEARCH METHODS AND

CASE STUDY DESCRIPTION

The case studies focuses on a medium sized city

(referred to later in the text as City) in Finland. The

City has a key role in organizing the healthcare

services for the citizens in the municipal area in close

cooperation with other local and national level

authorities. In order to provide empirical insights of

the current situation of using benchmarking as a tool

for knowledge management and development

activities, semi-structured interviews and facilitated

workshops were organized in first case. The

participants represented the different service units

with various positions in the City’s organisations. A

total of 30 interviews were conducted from December

2020 to January 2021, recorded and transcribed

afterwards. The interviewees’ positions in the

organization’s hierarchy varied from coordinators

on the operational level to the upper management.

The interviews were analysed using content analysis.

The workshops were held in spring and autumn 2021.

The second case had six facilitated workshops in

autumn of 2021. The participants represented

different health care and rescue service units with

various positions in the organizations of the

municipalities in Pirkanmaa area. With total 55

participants of which some of the participants were

taking part of several workshops. During the

workshop the more detailed explanation of the results

was asked from the participants to get deeper

understanding of the benchmark activities in

Wellbeing services county of Pirkanmaa. In the

following section we introduce, how the

benchmarking concept was understood, how the

information was stored and knowledge shared as well

as the challenges and benefits of benchmarking

identified in the case studies.

4 CASE STUDY RESULTS

In the current situation, benchmark is understood as

learning from others, the exchange of best practices,

experiences and exchange of knowledge. The

important role of benchmarking was in the utilization,

evaluation and comparison of different issues

concerning the knowledge obtained. Benchmarking

enabled the own positioning of the City with

regarding to health care providers with different

actors, countries or cities.

Currently, benchmarking activities are carried out

in different service units. In some units,

benchmarking has become part of the work activities

and culture, while on the other hand, benchmarking is

not considered to be part of the work tasks at all in

some units, although there is pressure for change.

Benchmarking activities currently lack planning and

systematicity, and the emphasis is more on the

random and unstructured nature of benchmarking

operating management. The basis and objectives of

benchmarking are derived from the City's strategy

(especially in development projects, new services or

emphasized priorities); however, this needs more

active internal presentation and structuring.

Benchmarking activities do not appear as part of the

units’ annual planning, except large for scale projects,

in which case the needs for benchmarking are

comprehensively written down in the action plan (i.e.

Knowledge Management and Benchmarking for Health Care System Development Activities

165

what items need to be benchmarked, goal setting is

considered and scheduled and the implementation of

the results is planned).

The cases addressed the utilisation of benchmark

data and information, storage, sharing and

implementation in benchmark activities. Currently,

benchmarking information is not collected, stored or

shared systematically using any program or tool. The

information remains with the individual employee,

who thus accumulates large amounts of tacit

knowledge. Information storage is often in a private

computer or network folder, and access to the data is

limited. The means for result sharing are team

meetings or management teams. Currently, the

benchmark information and results are distributed

randomly, and there is no mutually agreed practice for

storing or sharing of benchmark information and

result. Therefore there was a wish to develop a wide

range of services provided by the organisation, such

as a handbook or model for making an impact on

benchmarking, a means of prior preparation, easy and

practical guidance, a way to implement

benchmarking, training in benchmarking, and also

practical assistance for the benchmarking process and

supporting materials for learning and utilization of

health care IT systems.

Empirical results highlighted increasing

understanding of benchmarking as such, and the fact

that benchmarking process enhanced their

understanding of the benchmarked issue. In

benchmarking, "there is no need to reinvent the

wheel", but benchmarking makes it easier to set the

scale, identify errors, gain objectivity and

phenomenon-based examination” said one of the

interviewees. Benchmark activities are often reflected

positively in the operating and work culture, creating

trust, openness and co-creation between different

actors in international cooperation.

The benefits of benchmarking identified in the

workshops, especially in the health care context

include learning from others and particularly, the

need to make tacit knowledge visible and shared.

Benchmarking offers a tool for forming the security

situational picture of the overall health and welfare

sector at the national level, for example (i.e. risk

evaluation or administration or leadership needs).

Beside learning and the situational picture,

benchmarking reveals the opportunities for co-

operation between different actors in a certain field.

Furthermore, technology is developing rapidly and

technological solutions in the health and wellbeing

sector require constant learning, and benchmarking

was seen as a tool for co-learning.

There are also challenges or obstacles to

benchmarking. Our results highlighted time,

competence and human resources as the challenges

faced in benchmarking. The network challenges

identified were different cultures, differences in

services and systems (i.e. Finnish social security,

education arrangements, etc.) and language issues.

However, the City's internal policies and rules (i.e.

travel rules) constrain benchmarking operations. The

identified challenges in health care become

emphasized in the transformation of the operational

environment; technology shapes the operational

environment and the learning requirements are

continuous: increasing customer needs lead to a more

and more to customer-oriented approach and different

experiences from other actors are needed for service

development. The participants emphasized the need

for support for evaluation, object definition and

vision formulation, and benchmarking is one tool for

these. The empirical results highlighted several

aspects of the benefits as well as challenges (Table 1).

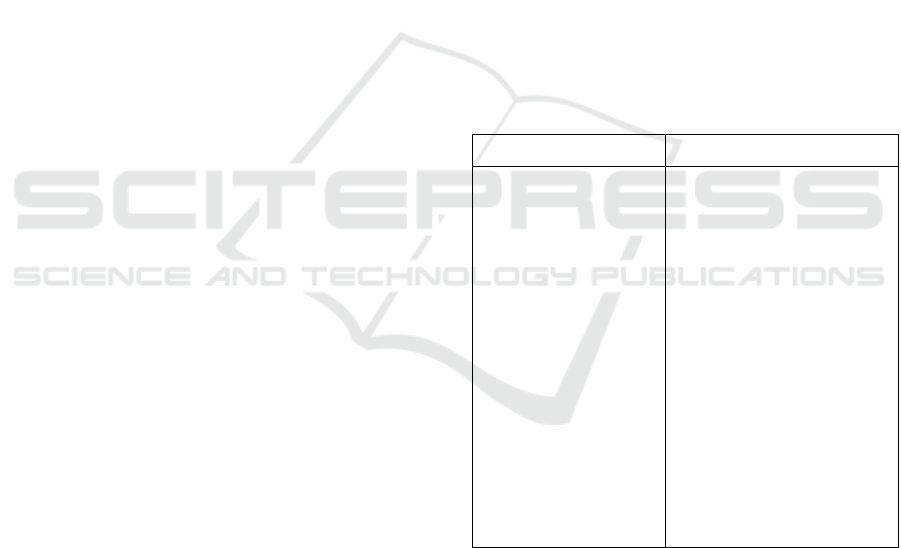

Table 1: Identified benefits and challenges of

benchmarking in the case studies.

BENEFITS CHALLENGES

LEARN

Lessons learned,

expanding your own

understanding and

experiences, new

insights

ACT

Trust, cooperation,

internationality, set

scale for operations,

positioning

DEVELOP

New ideas, piloting, co-

creation, reflected in the

operating culture,

enhanced knowledge,

attitude change

RESOURCES

Lack of time for

benchmarking, implementing

new ideas random

INFORMATION

Person-linked tacit

knowledge, employee

turnover, documentation,

knowledge exchange and

sharing

CULTURE

System and cultural

differences, language issues,

comparability, alignment

with context

PROCEDURE

Bureaucracy, policy

5 CONCLUSIONS AND

DISCUSSION

At its best, benchmarking information should be of

high quality and easily accessible to support decision

makers. In order to ensure the functioning of this

chain, it is necessary to reconcile both the more

technical side (such as functioning information

systems to enable data storage) and the softer, more

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

166

human side. One practical tool for information

processing could be the information management

process model developed by Choo (2002), which

begins with defining information needs and acquiring

information. The data analysis phase is when data

collected from different sources is analysed. The next

step in the process is information sharing and

utilisation. However, information will only become

valuable when it is used in decision-making and

operational development, and when real changes in

the organisation's operations take place. It is essential

to evaluate the changes through measuring and what

is learned from the benchmarking process. In that

way, by identifying new development needs, the

information management cycle starts again.

As in the benchmarking process, the information

process requires the selection of the theme and the

definition of the concept of the issue; what is actually

to be examined in benchmarking. The object setting

for benchmarking guides the benchmarkers and

potential data users to consider what is the desired

outcome as well as who will benefit from the results

and how.

The next step is to define the data source for data

acquisition and to define how the data source will be

analysed. Data can be retrieved using different

databases, and it is essential is to identify the most

relevant data for the benchmarking purpose. The

benchmark information obtained needs

implementation steps. The results gained in the

benchmark information process can guide

knowledge-based decision making.

In summary, more effective benchmarking can be

achieved by strengthening the strategy orientation

and systematic approach. Strategy-driven benchmark

practices ensure that benchmarking is targeted

correctly. In turn, a systematic approach can be

increased through systematic data collection, sharing

and documentation, and by harnessing operations in

networks as a goal-oriented part of the development

of the organisation's competence and operations.

Finally, the results obtained should mirror the

objectives set for the benchmarking (how the targets

were achieved or why they were not met).

This study has several limitations that affect

especially the generalizability of the research results.

The empirical data is gathered only from two cases,

both representing Finnish health care system, which

in turn is a representative of the so-called Nordic

health care system. Furthermore, empirical data was

gathered only by qualitative means, thus the study is

lacking quantitative evidence. However, this study

was able to provide initial empirical insights of the

benefits and challenges that health care service

organizations face in development activities. Further

empirical studies are needed, as well as more solid

analysis of the overall KM process and its relation to

benchmarking phases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is a part of the RECPHEALS project,

funded by Academy of Finland, Special funding for

research into crisis preparedness and security of

supply.

REFERENCES

Anand, G. and Kodali, R., 2008. Benchmarking the

benchmarking models. Benchmarking: An

International Journal, Vol. 15(3), pp. 257-291.

doi.org/10.1108/14635770810876593.

Andersen, B. & Moen, R. 1999. Integrating benchmarking

and poor quality cost measurement for assisting the

quality management work. Benchmarking: An

International Journal, Vol. 6(4), pp. 291-301.

Bhutta, M., Huq, F. 1999. Benchmarking – Best Practices:

An Integrated Approach. Benchmarking: An

International Journal, Vol 6 (3), pp. 254-268.

Braadbaart, O. and Yusnandarshah, B. 2008, Public sector

benchmarking: a survey of scientific articles, 1990-

2005, International Review of Administrative Sciences,

Vol. 74(3), pp. 421-433.

Castro, V. & Frazzon, E.M., 2017. Benchmarking of best

practices: an overview of the academic literature.

Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 24(3),

pp. 750-774. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-03-2016-0031.

Chase, R. L. 1997. Knowledge Management

Benchmarks. The Journal of Knowledge Management,

Vol.1(1), pp. 83-92.

Choo, C.W. 2002. Information management for the

intelligent organization: the art of scanning the

environment. Medford, New Jersey, Information

Today, Inc.

Feizabadi, J., Maloni, M. and Gligor, D., 2019.

Benchmarking the triple-A supply chain: orchestrating

agility, adaptability, and alignment. Benchmarking: An

International Journal, Vol. 26 (1), pp. 271-295.

https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-03-2018-0059.

Francis, G. & Holloway, J. 2007. What have we learned?

Themes from the literature on best-practice

benchmarking. International Journal of Management

Reviews, 9(3), pp. 171-189. doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-

2370.2007.00204.x.

Grayson, C. J. Jr. 1992. Taking on the world. The TQM

Magazine, Vol. 4(3), pp. 139-142. doi.org/10.1108

/09544789210034365

Hong, P., Hong, S.W., Roh, J.J. and Park, K. 2012.

Evolving benchmarking practices: a review for research

Knowledge Management and Benchmarking for Health Care System Development Activities

167

perspectives, Benchmarking: An International Journal,

Vol. 19(4/5), pp. 444-462.

Irfan, I., Sumbal, M.S.U.K., Khurshid, F. and Chan, F.T.S.

2022. Toward a resilient supply chain model: critical

role of knowledge management and dynamic

capabilities. Industrial Management & Data Systems,

Vol. 122(5), pp. 1153-1182. doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-

06-2021-0356

Keskimäki, I., Tynkkynen, L.-K., Reissell, E. et al. 2019.

Finland: health system review. World Health

Organization. Regional Office for Europe, European

Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

Kim, S. & Lee, H. 2010. Factors affecting employee

knowledge acquisition and application capabilities.

Asia-Pacific Journal of Business

Administration, Vol. 2(2), pp. 133-152.

Lo Sardo, D.R., Thurner, S., Sorger, J., Duftschmid, G.,

Endel, G., Klimek, P. 2019. Quantification of the

resilience of primary care networks by stress testing the

health care system. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1904826116. 2019.

Mafabi, S., Munene, J. C., & Ahiauzu, A. 2013.

Organisational resilience: Testing the interaction effect

of knowledge management and creative climate.

Journal of Organizational Psychology, 13(1/2), pp. 70-

82.

Massa, S., & Testa, S. 2004. Innovation or imitation?

Benchmarking: a knowledge‐management process to

innovate services. Benchmarking: An International

Journal, Vol. 11(6), pp. 610-620. doi.org/10.1108/

14635770410566519

Nonaka, I (1994) A dynamic theory of organizational

knowledge creation. Organization Science 5(1), pp. 14–

37.

Raymond, J. 2008. Benchmarking in public procurement,

Benchmarking: An International

Journal, Vol. 15(6), pp. 782-793.

Sammarra, A. and Biggiero, L. 2008. Heterogeneity and

specificity of inter-firm knowledge flows in innovation

networks, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 45(4),

pp. 800-829.

Sharma, R. S., Iqbal, M. I. N. A., & Victoriano, M. M. 2013.

On the use of benchmarking and good practices for

knowledge management for development. Knowledge

Management Research & Practice, 11(4), 346-360.

Shiem‐Shin Then, D. 1996. Minimum data sets ‐ finding

the balance in benchmarking. Facilities, Vol. 14(1/2),

pp. 47-51. doi.org/10.1108/02632779610108495

Spendolini MJ., 1992. The Benchmarking Process.

Compensation & Benefits Review, 24(5), pp. 21-29.

doi:10.1177/088636879202400505.

Watson, G. H. 1994. A Perspective on Benchmarking.

Benchmarking for Quality

Management & Technology, Vol. 1(1), pp. 5-10.

Wolfram Cox, J.R., Mann, L. & Samson, D. 1997.

Benchmarking as a Mixed Metaphor: Disentangling

Assumptions of Competition and Collaboration.

Journal of Management Studies, 34, 285-314.

doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00052.

Zairi, M. 1994

. Benchmarking: The Best Tool for

Measuring Competitiveness. Benchmarking for

Quality Management & Technology, Vol. 1(1), pp. 11-

24.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

168