Sharing Knowledge in the Social Media Era: Strengths and

Weaknesses for Knowledge Workers

Kamla Ali Al-Busaidi and Ibtisam Al-Wahaibi

College of Economics & Political Science, Sultan Qaboos University, University Street, Al-Khod, Oman

Keywords: Knowledge Sharing, Social Media, Knowledge Workers.

Abstract: Sharing knowledge is a very critical process for professional knowledge workers as it enables the creation

and accumulation of individual and organizational knowledge. The use of information and communication

technologies (ICT) and social media platforms to boost formal and informal knowledge sharing among

knowledge workers is inevitable, and the recent COVID-19 pandemic has forced digital transformation. This

study aims to examine the strengths and weaknesses of social media platforms for sharing knowledge by

assessing its characteristics from knowledge management (KM) and information security perspectives. Hence,

the study assesses the capability of social media platforms as a KM platform in terms of reach, depth, richness,

aggregation, confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Based on the literature review, the main strengths of

social media platforms are reach, richness, and availability, whereas some weaknesses are related to

confidentiality and depth. The findings of this research can help researchers in this area, and help

organizations and decision-makers set policies for sharing knowledge through social media platforms.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge workers are the core resource of the

knowledge economy. They are individuals with high

levels of creativity, formal education, and learning,

and apply their analytical and theoretical knowledge

to solving problems in their field of expertise; the

productivity of knowledge workers is the most

valuable asset in the 21st century (Drucker, 1999).

Knowledge has become the key resource and

organizations can gain sustainable advances from

“what it collectively knows, how efficiently it uses

what it knows and how quickly it acquires and uses

new knowledge” (Davenport & Prusak, 2008).

Knowledge sharing is a critical yet challenging

process in knowledge management because it

depends on knowledge workers’ willingness to share

their best practices. The knowledge sharing process

can enhance an organization’s operational and

strategic plans and impact several of its aspects:

employees, customers, business processes, products,

and finance (Becerra-Fernandez et al., 2014).

Information and communications technologies

are critical for knowledge sharing in today’s global

and digital society. The COVID-1 pandemic has

illustrated that ICT is the only option or the most

preferred option for knowledge workers’

collaboration and knowledge sharing. Social media

platforms are a booming technology among

knowledge workers. They provide knowledge

workers with several functionalities, including email,

chat, discussion forum tools, content management,

document management, search functionality, and

virtual meetings. The use of social platforms for KM

facilitates sustainability and allows organizations to

manage challenges. The characteristics of social

media platforms, such as collaboration, ease of use,

convenience, effectiveness, and implementation

promote their use for KM for small and medium-sized

organizations (Given et al., 2013). Organizations

utilize social media platforms for relationship

management with customers (Büyüközkan & Ilıcak,

2019) and for e-commerce (Abed et al., 2015). Social

media platforms enable knowledge workers to

strengthen bonds with their co-workers (Yoganathan

et al., 2021), and facilitate employee online learning

and education, improved interactivity (Al-Busaidi et

al., 2017), and employee agility (Pitafi et al., 2020).

However, there is no technology that is without

risk, and according to the literature, social media

platforms include several serious potential threats,

such as security, privacy, personal identity,

information overload, and productivity loss (Al-

192

Al-Busaidi, K. and Al-Wahaibi, I.

Sharing Knowledge in the Social Media Era: Strengths and Weaknesses for Knowledge Workers.

DOI: 10.5220/0011550400003335

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2022) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 192-199

ISBN: 978-989-758-614-9; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Busaidi et al., 2017; Marchegiani et al., 2020), all of

which might further disrupt already challenging

knowledge sharing in organizations.

To help in outlining the potential opportunities

and threats for sharing knowledge through social

media platforms, this study aims to answer the

research question: what are the strengths and

weaknesses of social media platforms for knowledge

workers? Consequently, this study aims to examine

the characteristics of social media systems (strengths

and weaknesses) from knowledge management and

information security perspectives. IT researchers

adopt SWOT to strategically analyze and understand

an organization’s current status in any IT deployment

(Al-Busaidi, 2014; Phadermrod et al., 2019). SWOT

enables organizations to identify a good fit that

maximizes a firm’s strengths and minimizes its

weaknesses, seizes opportunities, and eliminates

threats.

From a knowledge management perspective,

Becerra-Fernandez et al. (2014) indicated that a

knowledge management system should provide

reach, depth, richness, and aggregation. From an

information security perspective, Anderson (2003)

underlined three information system security

dimensions: Confidentiality, Integrity, and

Availability (CIA). Hence, the study assesses the

capability of the social media platform as a KM

platform in terms of reach, depth, richness,

aggregation, confidentiality, integrity and

availability.

2 BACKGROUND LITERATURE

2.1 Knowledge Workers & Knowledge

Sharing

Knowledge workers are the core resource and driving

force of the knowledge economy. Knowledge

workers are rapidly becoming the largest single group

in the workforce of every developed country

(Drucker, 1999), and have become an asset for every

organization based on their intellectual capital (Al-

Busaidi & Olfman, 2017; Nezafati et al., 2021). The

term ‘knowledge worker’ is attributed to Peter

Drucker; knowledge workers are individuals with

high levels of creativity, formal education, and

learning, and apply their analytical and theoretical

knowledge to solving problems in their field of

expertise to develop new products or services

(Drucker, 1999). They allow exercising considerable

autonomy and discretion in performing their work

(Viñas-Bardolet et al., 2020). Examples of knowledge

workers include professionals such as teachers,

lawyers, architects, physicians, nurses, engineers, and

scientists (Frick, 2010).

The productivity of knowledge workers is the

most valuable asset of the 21st century (Drucker,

1999). Knowledge has become the key resource and

organizations can gain sustainable advances from

“what it collectively knows, how efficiently it uses

what it knows and how quickly it acquires and uses

new knowledge” (Davenport & Prusak, 2008). A

knowledge worker’s productivity is determined by

the “extent a knowledge worker delivers outputs or

achieves the intended goals of his/her job in a

creative, efficient and effective way within a specific

time period considering his/her own competencies

(knowledge, skills and standard abilities required for

the job)" (Butt et al., 2019, pg. 1771).

Knowledge workers may face several challenges.

KM engagement of knowledge workers is a crucial

challenge for organizations in the twentieth century

(Butt et al., 2019). In order for knowledge workers to

be creative, they must exist as free individuals who

can liberally challenge their knowledge and

imagination (Shin et al., 2021). In terms of

technology use for knowledge workers, three specific

characteristics may “challenge established views on

computer support for office work; diversity of output,

low dependence on filed information and importance

of spatial layout and materials” (Kidd, 1994).

The literature identified several tasks and

activities for knowledge workers in terms of

traditional KM activities/processes. Gold et al. (2001)

KM processes included knowledge acquisition,

knowledge conversion, knowledge application, and

knowledge protection. Some researchers (Alavi &

Leidner, 2001) developed more than one framework

for KM processes; one of these included knowledge

creation, knowledge storage/ retrieval, knowledge

transfer, and knowledge application (Alavi &

Leidner, 2001). According to Becerra-Fernandez et

al. (2014), KM processes include knowledge

discovery, knowledge storage, knowledge sharing,

and knowledge application.

Knowledge sharing is a critical and challenging

process in knowledge management because it

depends on knowledge workers’ willingness to share

their best practices.

Knowledge sharing plays a major role in creating

organizational memory (Davenport & Prusak, 1998;

Becerra-Fernandez et al., 2014; Nezafati et al., 2021).

Knowledge sharing includes subtasks and sub

processes. According to Becerra-Fernandez et al.

(2014), Knowledge sharing process includes

socialization (sharing tacit knowledge) and exchange

Sharing Knowledge in the Social Media Era: Strengths and Weaknesses for Knowledge Workers

193

(for sharing explicit knowledge). Information and

communication technologies can enhance the

effectiveness and efficiency of the knowledge sharing

process. Several organizational mechanisms and

information and communications technologies (ICT)

can be adopted for knowledge sharing. Mechanisms

such as brainstorming retreats, cooperative projects,

conferences, employee rotation, and technologies

such as video-conferencing, electronic discussion

groups, and email can be used to share tacit

knowledge. Explicit knowledge sharing mechanisms

may include memos, manuals, letters, presentations,

etc., whereas KM technologies may include team

collaboration tools, groupware technologies, and

web-based access to databases. Community of

practice is the basic building block for knowledge

sharing; directories of experts and mapping the flow

of knowledge are critical elements for knowledge

sharing (Davenport & Prusak, 1998; Dalkir, 2017).

Traditional ICT can be used to enhance the

knowledge sharing process, such as communication

and collaboration tools, groupware, databases,

internet technologies, and portals. Current social

media tools for knowledge workers include wikis,

blogs, chats, discussion forums, and several platforms

such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, etc.

(Al-Busaidi, 2014; Al-Busaidi et al., 2017; Pitafi et

al., 2020).

2.2 Social Media Platform for Sharing

Knowledge

Advanced social media tools have brought about

changes in the way people interact, communicate, and

share content, and have attracted global attention due

to their pervasiveness and social impact (Ahmed et

al., 2019). Social media tools include micro blogs,

such as Twitter; personal blogs; word-of-mouth

forums; social networking services (SNS), such as

MySpace and Facebook; and video and picture

sharing applications, such as Flickr and YouTube

(Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010). Moreover, mobile apps –

such as Skype, WhatsApp, Tango, and Viber - are

used among groups for knowledge sharing.

These types of social media tools are considered

prominent and well-established spaces for creating

knowledge sharing channels, where people are able to

find other individuals with similar interests and share

their thoughts with them (Bilgihan et al., 2016).

The main use of social media among employees

is communication. Social media tools contribute

directly to horizontal and vertical communication

within organizations (Ma et al., 2020). Social media

platforms are also used for internal brand building

(Yoganathan et al., 2021), effectively guiding the

opinions of employees, and involving them in

managerial decision-making processes.

Another use of social media among employees is

for learning purposes; empirical findings show that

the users of social technologies in workplace learning

value the interactivity, peer support, and instant

feedback offered by these tools, and that the more the

employees use social media at work, the more they

learn. In more specific examples, empirical evidence

from case studies showed that wikis were efficient as

corporate tools in informal learning (Milovanović et

al., 2012), mobile Web 2.0 applications were

effective aids for informal learning in the workplace

(Gu et al., 2014), and virtual social environments

were useful in mentoring employees (Hamilton et al.,

2010), enabling team learning, and creating

collaborative learning atmospheres (Bosch-Sijtsema

and Haapamäki, 2014).

3 SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORM

CHARACTERISTICS

This study assesses the strengths and weaknesses of

using social media platforms for sharing knowledge

by examining their characteristics from a KM

perspective (reach, depth, richness, and aggregation)

based on Becerra-Fernandez et al. (2014); this is also

based on an IS security perspective (confidentiality,

integrity, and availability), which was created by

Anderson (2003). From an IS security perspective,

confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) are

essential dimensions according to IS security

researchers (Anderson, 2003; Samonas & Coss,

2014).

According to the KM researchers, “one possible

way of systematically viewing the IT is to consider

the capabilities it provides in four important aspects:

reach, depth, richness, and aggregation” (Becerra-

Fernandez et al., 2014; Daft & Lengel, 1986; Evans

& Wurster 1999). Knowledge security and protection

are also critical issues for KM platforms (Gold et al.,

2001; Jennex & Durcikova, 2014).

3.1 Reach of the Social Media Platform

Reach refers to access and connection and the

efficiency of such access (Becerra-Fernandez et al.,

2014). Reach ideally refers to being able to connect

to “anyone, anywhere (Keen, 1991). Reach can also

be considered as the distance data must travel for its

exchange (Bleeker, 2020).

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

194

One strength of social media is that it increases

the reach of communication (El Ouirdi et al., 2015).

Social media can have a huge impact in reaching

global audiences and providing an open portal to

events unfolding in real-time (Johns, 2019). Social

media facilitates interaction, communication, and

building better and wider connections with co-

workers (Yoganathan et al., 2021). Organizational

members can collaborate and communicate remotely

(Zhang et al., 2020).

For instance, Rowan-Kenyon (2016) indicated

that the strength of social media in higher education

is that it allows professionals to create a community

around a common interest despite the distance

between them. Bizzi (2019) indicated it allows better

communication with customers, traders, social media

sources, and stakeholders. Furthermore, Bertoni

(2012) noted that social media platforms support

young engineers in exploiting the network of

connections of the more experienced engineers.

Hence, social media platforms enhance reach by

enabling vertical and horizontal communication (Ma

et al., 2020) among people within and across

organizational boundaries (Kwayu et al., 2021).

3.2 Depth of the Social Media Platform

Depth refers to the detail and amount of information

that can be effectively communicated over a medium

(Becerra-Fernandez et al., 2014). This dimension

relates to the aspects of bandwidth and customization

(Evans & Wurster, 1999).

In terms of depth of the social media platform for

KM, Allan (2019) indicated that the weakness of KM

in social media is that it does not really allow detailed

knowledge sharing entries. Fernandez (2009)

indicated that the weakness of social media in

libraries is that some have limitations on the amount

of information you can input. In addition, Bertoni

(2012) mentioned that social media platforms do not

sufficiently store and classify knowledge over long

periods of time. In contrast, Al-Busaidi (2014)

indicated that one of the strengths of social media is

information storage capacity.

3.3 Richness of the Social Media

Platform

The richness of a medium is based on its ability to:

“(a) provide multiple cues (e.g., body language, facial

expression, tone of voice) simultaneously; (b) provide

quick feedback; (c) personalize messages; and (d) use

natural language to convey subtleties (Daft and

Lengel 1986)” (Becerra-Fernandez et al., 2014, pg.

47).

One strength of social media is that it increases

the richness of communication (El Ouirdi et al.,

2015), and it also offers rich data that facilitate robust

analysis (Keppeler & Papenfuß, 2021). One strength

of KM through social media is that it enables posting

video tutorial walk-throughs of complex tasks on

specialized databases (Allan, 2019).

A social media platform is a rich tool for KM. The

strength of social media related to KM is the ability

to upload documents, images, and content that can be

easily stored, recovered, and disseminated (Narazak

et al., 2020). Social media also enables the recording

and sharing of contextual knowledge (mainly know-

why and know-how), and the capturing and

structuring of conversational knowledge (Bertoni,

2012). In addition, it facilitates both structured and

unstructured knowledge sharing (Grant, 2016).

For instance, in personal branding, Johnson

(2017) indicated that social media enables the use and

sharing of pictures, videos, and image-oriented

illustrations of users and their abilities. In customer

relationship management, Büyüközkan and Ilıcak

(2019) noted social enabled engagement with

customers via a variety of tools on social media, such

as videos, images, and sounds. Furthermore, in

competitive intelligence, Kim et al. (2016) indicated

that the strength of social media is that it is a

significant resource for understanding customer

sentiments and satisfaction, as well as the reputation

of the products/services

Videos enable the communication of body

language and voice tone. Thus, richness is a major

strength of social media platforms.

3.4 Aggregation of the Social Media

Platform

IT has significantly enhanced the ability to store and

quickly process information. This enables the

aggregation of large volumes of information drawn

from multiple sources (Becerra-Fernandez et al.,

2014).

One of the main strengths of social media

platforms is integration with social media and

collaboration tools, and links to mobile applications

(Al-Busaidi, 2014). The geographic information

system (GIS) information embedded in mobile

devices enables the integration of social messages

with the GIS information (Xu et al., 2016). Users can

share the spatial information in the posted message

(Xu et al., 2016). In addition, another integration

strength of social media usage in knowledge sharing

Sharing Knowledge in the Social Media Era: Strengths and Weaknesses for Knowledge Workers

195

and business decision-making in organizations is

using tools such as “data visualisation” and the “data

dashboard” (Siti-Nabiha et al., 2021).

3.5 Confidentiality of the Social Media

Platform

Confidentiality means that only authorized users can

take advantage of information stored on the computer

(Samonas & Coss, 2014). Researchers (Al-Busaidi,

2014; Chi, 2021) indicated a few weaknesses in social

media platforms: lack of security, safety, and privacy.

Each of these issues underlines the confidentiality

issue.

For instance, users can see the interactions

between other users (Yang et al., 2021). Knowledge

leakage is also a major concern in social media

technologies (Bertoni, 2012).

In sharing knowledge in project management,

Hysa and Spalek (2019) indicated one major

confidentiality concern is the disclosure of project

data and confidential information through social

media platforms. Thus, social networking sites can

result in a vulnerability that criminals can exploit to

attack organizations (El Ouirdi et al., 2015).

However, other researchers, such as Chandran

(2016), had different perspectives and indicated that

ensuring a high level of privacy and confidentiality is

a strength of social media platforms. The lack of

users’ knowledge about social media privacy settings

causes the confidentiality breaches and leakage.

3.6 Integrity of the Social Media

Platform

Integrity means that information accuracy and

modification (making changes in the stored

information) must be restricted to only authorized

people (Samonas & Coss, 2014). It assures the

accuracy and consistency of the information

(Tausczik & Huang, 2020). Samonas and Coss (2014)

also indicated that modification of the data by

unauthorized users can be conducted without seeing

the information. Research indicated several views on

the information integrity of social media. One

positive issue is the exchange of relevant, useful, and

effective information and knowledge (Fernandez,

2009; Given et al. 2014; Grant, 2016; Hysa & Spalek,

2019; Ma et al., 2020; Yoganathan et al., 2021). One

major strength is that social media facilitates the

creation, editing, and exchange of web-based content

(Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010; Leidner et al., 2018) and

user-generated content (Given et al., 2014).

However, researchers (Al-Busaidi, 2014;

Razmerita et al., 2016) highlighted the issue of

information overload and irrelevance that might

impact information integrity. Venkatesh et al. (2013)

underlined the validity issue that can occur during

data collection and analysis through social media

platforms.

3.7 Availability of Social Media

Platforms

Availability means authorized users should be able to

use, refer to, or modify information at any time

(Samonas & Coss, 2014). One of the main strengths

of social media is that it is freely available (Al-

Busaidi, 2014; Fernandez, 2009; Johns, 2019).

For knowledge workers, the accessibility and

availability of social media platforms enables

employees to better cope with challenging or

ambiguous situations (Yoganathan et al., 2021). The

prominence of social media communication can

enhance knowledge exchange and support work

efficiency (Yang et al., 2021). For instance, Chi

(2021) indicated that infrastructure (e.g., good

internet access and modern computers) makes social

media available to facilitate information services

between librarians and university library users.

4 CONCLUSIONS & FUTURE

DIRECTION

4.1 Summary

This study aims to examine the capability of social

media platforms as a KM platform in terms of reach,

depth, richness, aggregation, confidentiality,

integrity, and availability. Based on the literature

review, the main reported strengths of social media

platforms for knowledge sharing are reach, richness

and availability, whereas some weaknesses are

related to confidentiality and depth. Aggregation was

also reported to some extent as a strength. The

integrity of social media platforms for knowledge

sharing was also mainly reported as a strength;

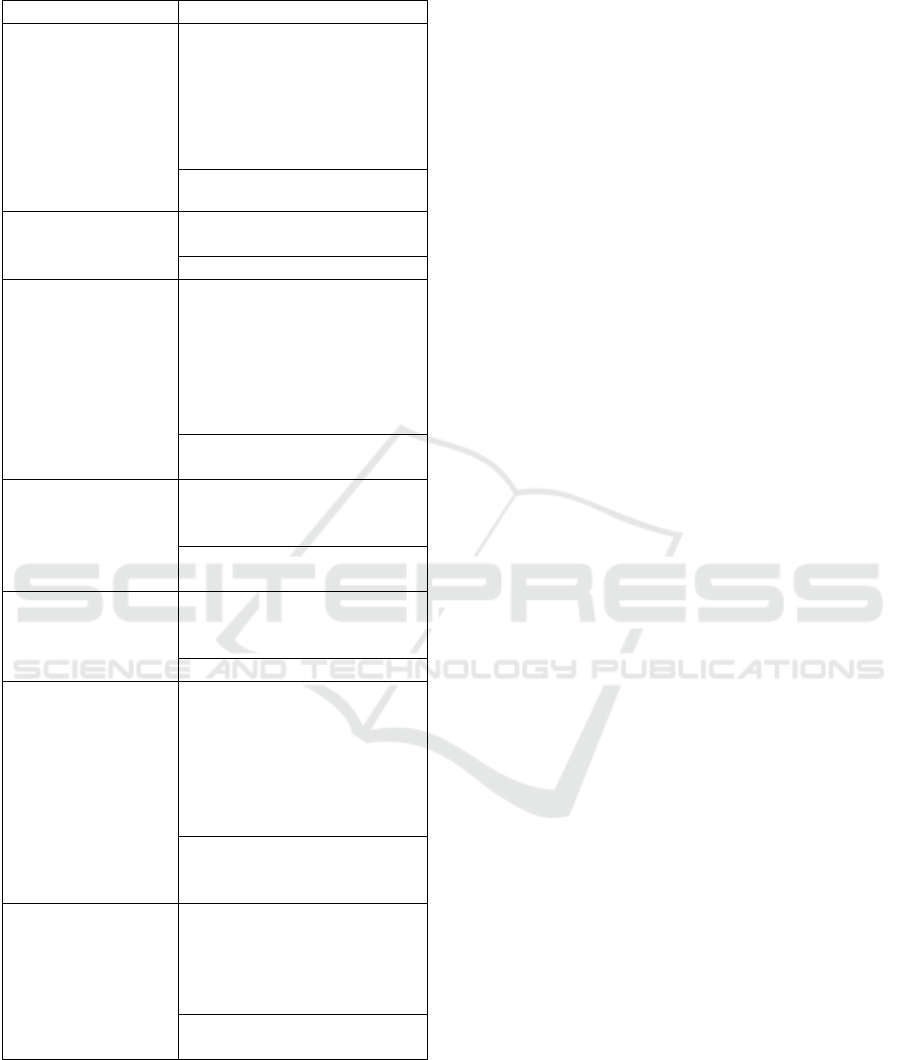

however, some concerns were raised about it. Table 1

illustrates these dimensions of the findings.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

196

Table 1: Social Media Dimensions for Knowledge Sharing

Dimension Supportin

g

References

REACH Strength: Bertoni (2012), El

Ouirdi et al. (2015), Rowan-

Kenyon (2016), Bizzi (2019),

Johns (2019), Ma et al. (2020),

Zhang et al., 2020), Kwayu et

al. (2021). Yoganathan, et al.

(2021).

Weakness: No supporting

re

f

erence.

DEPTH Weakness: Fernandez (2009),

Bertoni, (2012), Allan (2019).

Strength: (Al-Busaidi, 2014).

RICHNESS Strength: (Bertoni,(2012), El

Ouirdi et al.(2015),

Grant(2016), Kim et

al.(2016), Johnson (2017),

Allan (2019), Büyüközkan

and Ilıcak (2019), Narazak et

al. (2020).

Weakness: No supporting

reference.

AGGREGATION Strength: Al-Busaidi (2014),

Xu et al. (2016), Siti-Nabiha et

al. (2021).

Weakness: No supporting

reference.

CONFIDENTIALIT

Y

Weakness: Bertoni (2012), El

Ouirdi et al. (2015), Hysa

(2019), Yang et al. (2021).

Strength: Chandran (2016)

INTEGRITY Strength: Fernandez(2009),

Kaplan and Haenlein(2010),

Given et al.(2014),

Grant(2016), Leidner et

al.(2018), Hysa(2019), Ma et

al., (2020), Yoganathan et

al.(2021).

Weakness: Al-Busaidi(2014),

Venkatesh et al. (2013),

Razmerita et al.(2016).

AVAILABILITY

Strength: Fernandez(2009),

Al-Busaidi(2014), Chi (2021),

(Yang et al., 2021), Johns

(2019), Yoganathan et

al.(2021).

Weakness: No supporting

reference.

4.2 Implications

The use of information and communication

technologies to build-human resources is a

prerequisite for the development of a knowledge-

based economy, especially in developing countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the role of ICT

and social media as key collaboration and knowledge-

sharing tools among knowledge workers. This study

provides implications for researchers by identifying

the strengths and weaknesses of social media

platforms that might lead to potential opportunities

and threats. The literature indicated there are some

potential threats to using social media platforms (Al-

Busaidi et al., 2017; Marchegiani et al., 2020). Hence,

researchers should further investigate each weakness

and the related possible threats. The study also

provides implications for practitioners by providing

insights to help them on setting policies on their

organizational use of social media platforms and in

helping individuals use social media to enhance their

productivity and innovation with manageable threats

and risks.

4.3 Future Directions

This proposed study aims to integrate qualitative

(literature review and interviews) and quantitative

(survey) approaches. A questionnaire will be

developed and a survey will be conducted to

empirically test this proposed framework among

knowledge workers with different profiles and in

different sectors. In addition, a deep investigation on

the different characteristics of different types of social

media platforms is critical as some characteristics

might be different in different social media platforms,

which may impact its utilization for knowledge

sharing by knowledge workers. Furthermore, the

cross-cultural investigation will enrich the findings.

REFERENCES

Abed, S. S., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Williams, M. D. (2015).

Social media as a bridge to e-commerce adoption in

SMEs: A systematic literature review. The Marketing

Review, 15(1), 39-57.

Ahmed, Y. A., Ahmad, M. N., Ahmad, N., & Zakaria, N.

H. (2019). Social media for knowledge-sharing: A

systematic literature review. Telematics and

informatics, 37, 72-112.

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Knowledge

management and knowledge management systems:

Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS

Quarterly, 25(1), 107-136.

Al-Busaidi, K. A. (2014). SWOT of social networking sites

for group work in government organizations. VINE:

The journal of information and knowledge management

systems, 44 (1), 121 – 139.

Al-Busaidi, K. A., Ragsdell, G., & Dawson, R. (2017).

Barriers and benefits of using social networking sites

versus face-to-face meetings for sharing knowledge in

Sharing Knowledge in the Social Media Era: Strengths and Weaknesses for Knowledge Workers

197

professional societies. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst., 25(2), 145-

164.

Allan, C. (2019). Sharing is caring: Using knowledge

management to enhance subject librarian-student

contact. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 24(3-4), 123-130.

Anderson, J. M. (2003). Why we need a new definition of

information security. Computers & Security, 22(4),

308-313.

Chandran, D. (2016). Social media and HIV/AIDS:

implications for social work education. Social Work

Education, 35(3), 333-343.

Chi, D. T. P. (2021). Social media in academic libraries: a

swot analysis. Знак: проблемное поле

медиаобразования, 1 (39), 59-67.

Drucker, P. F. (1999). Knowledge-worker productivity:

The biggest challenge. California management review,

41(2), 79-94

Becerra-Fernandez, I., & Sabherwal, R. (2014). Knowledge

management: Systems and processes. Routledge, New

York, NY.

Bertoni, M. (2012). Social Technologies for Cross-

Functional Product Development: SWOT Analysis and

Implications. The 45th Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences, pp. 3918-3927.

Bilgihan, A. (2016). Gen Y customer loyalty in online

shopping: An integrated model of trust, user experience

and branding. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 103-

113.

Bizzi, L., (2019). The double-edged impact of social media

on online trading: opportunities, threats, and

recommendations for organizations. Business

Horizons, 62(4), 509–519.

Bleeker, A. (2020). Strengthening ICT and knowledge

management capacity in support of the sustainable

development of multi-island Caribbean SIDS, Studies

and Perspectives series-ECLAC Subregional

Headquarters for the Caribbean, No. 81

(LC/TS.2019/115 -LC/CAR/TS.2019/4), Santiago.

Boddy, J., & Dominelli, L. (2017). Social media and social

work: The challenges of a new ethical space. Australian

Social Work, 70(2), 172-184.

Bosch-Sijtsema, P. M., & Haapamäki, J. (2014). Perceived

enablers of 3D virtual environments for virtual team

learning and innovation. Computers in Human

Behavior, 37, 395-401.

Butt, M. A., Nawaz, F., Hussain, S., Sousa, M. J., Wang,

M., Sumbal, M. S., & Shujahat, M. (2019). Individual

knowledge management engagement, knowledge-

worker productivity, and innovation performance in

knowledge-based organizations: the implications for

knowledge processes and knowledge-based systems.

Computational and Mathematical Organization

Theory, 25(3), 336-356.

Büyüközkan, G., & Ilıcak, Ö. (2019). Integrated SWOT

analysis with multiple preference relations. Kybernetes.

48 (3), 451-470.

Daft, R.L. and Lengel, R.H. 1986. Organization

information requirements, media richness, and

structural design. Management Science, 32(5), 554–

571.

Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working

knowledge: How organizations manage what they

know. Harvard Business Press, Boston, Mass.

El Ouirdi, A. El Ouirdi, M. Segers, J & Henderickx, E.

(2015). Employees' use of social media technologies: a

methodological and thematic review. Behaviour &

Information Technology, 34:5, 454-464

Evans, P. and Wurster, T.S. 1999. Getting real about virtual

commerce. Harvard Business Review, 77(6), 85–94.

Fernandez, J. (2009). A SWOT analysis for social media in

libraries. Online, 33(5), 35-37

Keppeler, F., & Papenfuß, U. (2021). Employer branding

and recruitment: Social media field experiments

targeting future public employees. Public

Administration Review, 81(4), 763-775.

Frick, D. E. (2010). Motivating the knowledge worker.

Defense Intelligence Agency, Washington Dc.

Given, L. M., Forcier, E., & Rathi, D. (2013). Social media

and community knowledge: An ideal partnership for

non‐profit organizations. Proceedings of the American

Society for Information Science and Technology, 50(1),

1-11.

Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001).

Knowledge management: An organizational

capabilities perspective. Journal of management

information systems, 18(1), 185-214.

Grant, S. B. (2016). Classifying emerging knowledge

sharing practices and some insights into antecedents to

social networking: a case in insurance. Journal of

Knowledge Management,20(5), 898-917.

Hamilton, C., Langlois, K., & Watson, H. (2010). Virtual

Speed Mentoring in the Workplace-Current

Approaches to Personal Informal Learning in the

Workplace: A Case Study. International Journal of

Virtual and Personal Learning Environments

(IJVPLE), 1(2), 59-66.

Hysa, B., & Spalek, S. (2019). Opportunities and threats

presented by social media in project management.

Heliyon, 5(4), 1-28.

Jennex, M., & Durcikova, A. (2014). Integrating IS security

with knowledge management: Are we doing enough?

International Journal of Knowledge Management,

10(2), 1-12.

Johns B, (2019). Improve Reproducibility in clinical and

research applications. Stem Cells Translational

Medicine, 8(1), pp 1226–1229.

Johnson, K. M. (2017). The importance of personal

branding in social media: educating students to create

and manage their personal brand. International Journal

of Education and Social Science, 4(1), 21-27

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world,

unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social

Media. Business horizons

, 53(1), 59-68.

Keen, P. 1991. Shaping the future: Business design through

information technology. Boston: Harvard Business

School Press.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

198

Kidd, A. (1994, April). The marks are on the knowledge

worker. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on

Human factors in computing systems (pp. 186-191).

Kim, Y., Dwivedi, R., Zhang, J., & Jeong, S. R. (2016).

Competitive intelligence in social media Twitter:

iPhone 6 vs. Galaxy S5. Online Information Review,

40(1), pp. 42-61.

Kwayu, S., Abubakre, M., & Lal, B. (2021). The influence

of informal social media practices on knowledge

sharing and work processes within organizations.

International Journal of Information Management, 58,

p.102280.

Ma, L., Zhang, X., & Ding, X. (2020). Enterprise social

media usage and knowledge hiding: a motivation theory

perspective. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(9),

2149-2169.

Marchegiani, L., Brunetta, F., & Annosi, M. C. (2020).

Faraway, Not So Close: The Conditions That Hindered

Knowledge Sharing and Open Innovation in an Online

Business Social Network. IEEE Transactions on

Engineering Management, 69(2), 451-467.

Milovanović, M., Minović, M., Štavljanin, V., Savković,

M., & Starčević, D. (2012). Wiki as a corporate learning

tool: case study for software development company.

Behaviour & Information Technology, 31(8), 767-777.

Narazak R, Silveira Chaves M, Drebes Pedron C, (2020). A

project knowledge management framework grounded

in design science research. The journal of corporate

transformation, 27(3), pp 1-14.

Nezafati, N., Razaghi, S., Moradi, H., Shokouhyar, S., &

Jafari, S. (2021). Promoting knowledge sharing

performance in a knowledge management system: do

knowledge workers’ behavior patterns matter? VINE

Journal of Information and Knowledge Management

Systems. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-11-

2020-0202

Pitafi, A. H., Rasheed, M. I., Kanwal, S., & Ren, M. (2020).

Employee agility and enterprise social media: The Role

of IT proficiency and work expertise. Technology in

Society, 63, 101333.

Razmerita, L., Kirchner, K., & Nielsen, P. (2016). What

factors influence knowledge sharing in organizations?

A social dilemma perspective of social media

communication. Journal of knowledge Management,

20(6), 1225-1246.

Rowan-Kenyon, (2016). Social media in higher education.

Ashe Higher Education Report, 42(5), 7–128.

Samonas, S., & Coss, D. (2014). The CIA strikes back:

Redefining confidentiality, integrity, and availability in

security. Journal of Information System Security, 10(3),

21–45.

Siti-Nabiha, A. K., Nordin, N., & Poh, B. K. (2021). Social

media usage in business decision-making: the case of

Malaysian small hospitality organisations. Asia-Pacific

Journal of Business Administration, 13(2), pp 272-289

Tausczik, Y., & Huang, X. (2020). Knowledge generation

and sharing in online communities: Current trends and

future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 36,

60–64.

Viñas-Bardolet, C., Torrent-Sellens, J., & Guillen-Royo,

M. (2020). Knowledge workers and job satisfaction:

evidence from Europe. Journal of the Knowledge

Economy, 11(1), 256-280.

Xu, Z., Zhang, H., Hu, C., Mei, L., Xuan, J., Choo, K. K.

R., ... & Zhu, Y. (2016). Building knowledge base of

urban emergency events based on crowdsourcing of

social media. Concurrency and Computation: Practice

and experience, 28(15), 4038-4052.

Yang, X., Lyu, Y., Tian, T., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., & Zhang, X.

(2021, January). Rumor detection on social media with

graph structured adversarial learning. In Proceedings of

the twenty-ninth international conference on

international joint conferences on artificial

intelligence (pp. 1417-1423).

Yoganathan, V., Osburg, V. S., & Bartikowski, B. (2021).

Building better employer brands through employee

social media competence and online social

capital. Psychology & Marketing, 38(3), 524-536.

Zhang, X., Tang, J., Wei, X., Yi, M., & Ordóñez, P. (2020).

How does mobile social media affect knowledge

sharing under the “Guanxi” system? Journal of

Knowledge Management, 24(6), 1343-1367.

Sharing Knowledge in the Social Media Era: Strengths and Weaknesses for Knowledge Workers

199