I Wandered Lonely in the Cloud: A Review of Loneliness,

Social Isolation and Digital Footprint Data

Dominic Reedman-Flint

1

, John Harvey

1a

, James Goulding

1b

and Gary Priestnall

2

1

N/LAB, Nottingham University Business School, University of Nottingham, U.K.

2

School of Geography, University of Nottingham, U.K.

Keywords: Social Isolation, Loneliness, Human-Computer Interaction, Digital Trace Data.

Abstract: The harm that social isolation and loneliness can have on physical, mental, and emotional well-being is now

well evidenced. With social distancing and remote working now commonplace, the dangers of loneliness are

ever more acute. Consequently, information technologies have taken on renewed importance to support

healthy communication and reduce the negative impacts of social isolation. However, existing literature

remains highly conflicted as to the relationship between technology use and its impact on loneliness. This is

perhaps understandable: measures of loneliness have traditionally been examined within clinical settings, far

removed from the everyday realities of computational interactions. Yet data logged about such interactions

now offers potential to help identify isolation and loneliness and support those experiencing resulting health

issues. We present a scoping review of this domain, focusing on detection of loneliness and social isolation

through digital data. We interrogate a corpus of published articles from the HCI literature, identifying a series

of methodological, epistemological, and ethical tensions therein, as well as emerging opportunities for future

empirical study. We identify a need to examine such phenomena via actual behavioural data, rather than

reliance on historical proxies such as age and gender, to help modernize our understanding of this growing

social ill.

1 INTRODUCTION

"The world is the closed door. It is a barrier. And at

the same time it is the way through. Two prisoners

whose cells adjoin communicate with each other by

knocking on the wall. The wall is the thing which

separates them but it is also their means of

communication. … Every separation is a link."

The quote above by philosopher Simone Weil

(1997) draws on Plato’s concept of metaxu, meant

here as something that both separates and connects

simultaneously. It was originally intended to describe

the challenge of communion with God, but its

metaphor of a prison wall also serves as a useful

analogy for how contemporary researchers describe

technology and its effect on communication between

people more generally. Recent works summarising

loneliness and online social interaction have shown

how information technologies, and in particular

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4188-1900

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8892-6398

interconnected digital devices, appear in the literature

as both the cause of, and solution to, the growing

issue of loneliness (Dunbar, 2021; Hertz, 2021).

Much of the literature is therefore conflicted,

illustrating that the causal relationship between the

two categories is both complex and likely bi-

directional; such that the aetiology of loneliness is at

least partially context dependent. Technology

transforms social relations, and in doing so, creates

new opportunities for alienation and communion

alike.

Despite the complexity involved in potential

manifestations of loneliness, research conducted by

social neuroscientists (Cacioppo and Patrick, 2008)

provides scientific evidence that loneliness causes

physiological events that wreak havoc on our health.

Persistent loneliness leaves a mark via stress

hormones, immune function and cardiovascular

function (Knox and Uvnäs-Moberg, 1998) with a

cumulative effect that brings health outcomes similar

Reedman-Flint, D., Harvey, J., Goulding, J. and Pr iestnall, G.

I Wandered Lonely in the Cloud: A Review of Loneliness, Social Isolation and Digital Footprint Data.

DOI: 10.5220/0011578500003323

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2022), pages 225-235

ISBN: 978-989-758-609-5; ISSN: 2184-3244

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

225

to being a smoker (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010).

Furthermore, loneliness exacerbates the risk of

experiencing additional subsequent problems and

altering behaviour insofar as it increases the

likelihood ‘of indulging in risky habits such as drug

taking and plays a role in mental disorders such as

anxiety and paranoia’ (Griffin, 2010). Despite this,

many people experiencing loneliness do not interface

with medicalized settings; and few receive clinical

diagnosis or support. Due to the hidden nature of the

problem, estimates of loneliness are often absent from

national statistics despite potential to inform social

policy. As a result, researchers have often turned to

demographic proxies for loneliness, with much work

throughout the 20th century seeking to theorise the

phenomena, and the nature of those people

predisposed to it. In particular, the elderly (over 65s)

and disabled, widely cited in academia as being most

affected, underpin most analyses of loneliness

prevalence. Yet the UK’s Office of National Statistics

(ONS, 2018) and BBC, via the world’s largest

empirical study of loneliness (BBC, 2019), recently

showed that loneliness is far from constrained to these

communities; and affects the population in far more

ways than previously recognised

Recently, the issue has been further exacerbated

by Covid-19, and our increasing exposure to

conditions conducive to loneliness (Bu et al., 2020).

Dramatic societal change, lockdowns, and enforced

social distancing has spawned a flurry of research to

help identify those most at risk of loneliness and its

myriad health consequences (Ernst et al., 2022). Yet,

the mass transformation of work and socialization

into increasingly online settings has also created

opportunity for researchers: digital identification of

those at risk. Whether in cases where digital

technology exacerbates loneliness or in situations it

diminishes it, human-computer interactions leave

behind a rich corpus of digital logs. Such digital

footprint data, if handled responsibly, can offer new

avenues to help identify, characterize, and intervene

in this “wicked problem”. The development of big

data and ubiquitous digital architectures to log

everything from library records, transport

movements, health records, social interactions and

even shopping habits illustrates the wide range of

siloed information available; data that might be

harnessed to better understand vulnerability to

loneliness and to direct social policy accordingly.

With such potential, of course, comes risk:

approaches that depend on indirect, closed, or

proprietary data sources introduce new

methodological, ethical, and privacy challenges,

otherwise absent in clinical settings.

The overall aim of this work is therefore to

establish the contexts in which digital data are being

used when identifying people experiencing social

isolation or loneliness, or where data are being

inadvertently created by the interactions of those

people experiencing loneliness (particularly those

who are doing so in populations not typically

recognised within clinical settings). Unlike review

papers that have attempted to map the efficacy of

digital technologies as loneliness interventions from

a public health perspective (Shah et al, 2019; Ibarra et

al, 2020), we provide a scoping review of how social

isolation and loneliness interventions are already

conceived, discussed, and enacted within the

computing literatures. By examining epistemological

and methodological bases of previous research we

aim to expose some of the underlying intellectual

commitments and assumptions currently being made

in the field and contextualize ongoing debate. We first

outline the methodology and scoping approach used

to achieve this, before discussing emerging genres in

the field and the key analytical differences that

separate researchers. Finally, we discuss emerging

issues and empirical gaps in the domain that, if

addressed, can serve as the basis for addressing this

phenomenon.

2 METHDOLOGY

While ‘loneliness’ and ‘social isolation’ are well

accepted terms in everyday usage, definitions in

academic contexts vary significantly by scientific

discipline and empirical focus. Significant existing

work has sought to characterise loneliness and social

isolation through study of their respective aetiologies

from a public health perspective (Holt-Lunstad, 2017;

Elovainio et al., 2017; Stepto et al, 2013; Lubben,

2017). Various constructs are described in the

literature suggesting interconnectedness between the

conditions; and in much work the terms ‘loneliness’

or ‘social isolation’ are used interchangeably -

particularly in research which does not aim to

conceptualise the respective concepts. Yet there is

limited consensus here, with other research viewing

the conditions as entirely distinct and to be considered

independently (Matthews et al, 2016); and in

psychological and clinical research it is far more

common to differentiate the constructs. Social

isolation is typically described as the circumstance of

being physically alone or otherwise detached from

contact with friends, family, or society; Loneliness, in

contrast, is described as a negative psychological

response to such situations, commonly portrayed as

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

226

‘a subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of

companionship... [occurring] when we have a

mismatch between the quantity and quality of social

relationships that we have, and those that we want’

(Perlman and Peplau, 1981). Academic definitions

are contested for both terms, with some authors

speaking of multiple sub-types of loneliness (Weiss,

1975), yet a separation is commonly recognised

between them. As our intention is to synthesize

literature around these concepts, we do not challenge

such definitions - while the overlapping of language

creates challenges for comprehensive summarisation

of the field, it also highlights the need for consilience

and transdisciplinarity to support further advances.

Archetypal definitions of loneliness and social

isolation primarily came from diagnostic scales

developed in the latter part of the 20th century. Weiss

(1975) saw ‘social loneliness’ as a lack of or negative

change in social connections below a desired level,

whereas ‘emotional loneliness’ was a lack of deep,

meaningful (i.e. romantic or familial) connection.

This multidimensional approach to the study of

loneliness is not, however, reflected in the widely

used UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, 1996) which

treats loneliness as a unidimensional construct. While

this approach has been contested (Marangoni and

Ickes, 1989), Russell et al. (1984) have argued that,

despite different forms existing, that the UCLA scale

adequately summarises these different loneliness

states. UCLALS is the most widely used

measurement for loneliness, but several alternative

well-cited measures exist. Almost uniformly,

however, these predate widespread adoption of the

Internet and digital devices - whether de Jong

Gierveld’s Scale (De Jong-Gierveld, 1987), the

Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults

(DiTommaso and Spinner, 1993), Differential

Loneliness (Schmidt and Sermat, 1983) or the

Loneliness Rating Scale (Scalise et al, 1984).

One of the key, outstanding questions for digital

identification of loneliness, is therefore the extent to

which present-day research should revisit such

measures, given the rapid integration of technology

into our daily lives over the past two decades (e.g.,

mobile private messaging, social networking, and

livestreamed video). The impact the digital world has

had on our experience of loneliness and social

isolation remains unclear; do traditional metrics still

hold; and to what extent have traditional proxies

become anachronistic? Loneliness has predominantly

been identified in clinical settings through surveys

and self-diagnosis, or via direct medical assessment.

Do such environments overlook people in need of

support but who do not seek out practitioners, either

being unable or stigmatised from doing so? To

consider questions of this nature, Munn et al. (2018)

have advanced scoping reviews as useful tools to

examine emerging evidence; especially when it is still

unclear what other, more specific questions can be

valuably posed and addressed by future empirical

work. Such reviews aim to not only report on

evidence that informs practice in the field, but to

consider the way research has been conducted, and in

particular ‘in contrast to traditional literature reviews

scoping reviews are informed by an a priori protocol;

Are systematic; Aim to be transparent and

reproducible; and ensure data is extracted and

presented in a structured way’ (Munn et al., 2018).

This scoping review focuses on two databases

containing peer-reviewed papers in computing and its

associated sub-disciplines, the Association for

Computing Machinery (ACM) and the IEEE Xplore

(IEEE) digital libraries respectively. Both libraries

were searched, isolating abstracts containing the

terms ‘loneliness’ or ‘social isolation’. This produced

a total of 401 results, and the resulting corpus was

screened for non-English, inaccessible, or non-peer

reviewed articles or conference papers. Each article

was then reviewed to ensure that social isolation or

loneliness was not peripheral but a relevant empirical

or conceptual focus of the work. Papers either: (1)

identified social isolation or loneliness as part of their

sampling procedure; (2) used social isolation or

loneliness as a dependent or independent variable

within analysis; or (3) social isolation or loneliness

was specifically being explored or researched through

an inductive or conceptual approach. This process is

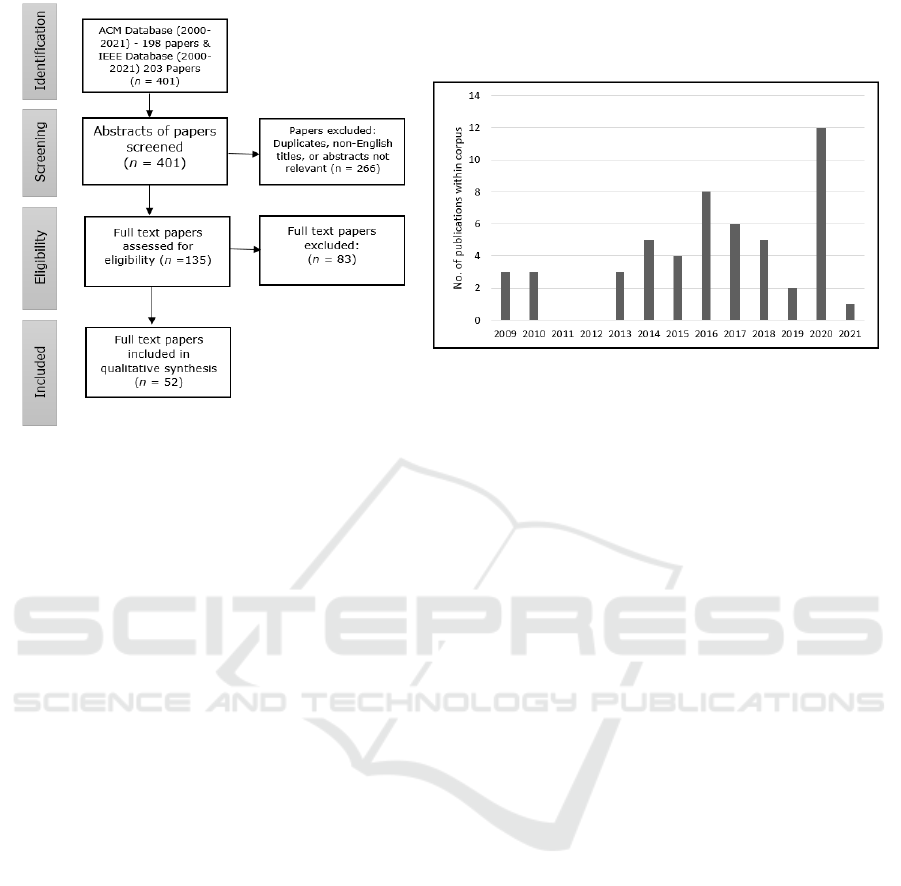

summarised via the PRISMA diagram in Figure 1.

The final output corpus yielded 52 articles, which

were taken forward to fine-grained analysis. Each

article was decomposed, and re-summarised into a

short commentary before then being analysed in

relation to a series of methodological questions.

Answers to these questions were tabulated, serving as

the basis thematic identification discussions between

the research team, who collaboratively identified

genres and epistemological commitments made by

the works.

The methodological research questions

considered are: (1) Is the work empirical (data

gathering) or conceptual? (2) Data provenance - if

data are gathered what is collected and how? (3)

Sampling - who is the focus of the research / who is

thought to be lonely? (4) Does the study aim to

identify people experiencing issues, intervene to help

people, or to conceptualize what loneliness is? (5) Is

loneliness or social isolation measured and if so, how;

is it a pre-existing measure or newly developed? (6)

I Wandered Lonely in the Cloud: A Review of Loneliness, Social Isolation and Digital Footprint Data

227

Is an expert identified within labelling (or not); who

gets to identify those being labelled lonely?; (7) What

methods were used to analyse loneliness data

generated? (8) what metadata is likely to exist as part

of the measures chosen e.g., social network data,

spatial data, or time series data; and (9) What

constitutes success and who are the beneficiaries?

The answers to these questions were then used to (a)

identify genres of work with clustered formulations

of loneliness problems/challenges addressed via

digital technology; (b) to examine contrasting

methodology and epistemology of studies in the field,

and (c) to indicate promising avenues for future

research.

3 ANALYSIS

52 papers were included in the final corpus. Figure 1

shows the earliest three papers from the corpus

(Zhang, 2009; Zhou et al., 2009; Waterworth and

Ballesteros, 2009) appeared in 2009, with a gradual

annual increase until 2020, which saw 12 relevant

papers published (search conducted 04/2021). 37

articles used established loneliness measures, of

which 16 used the UCLA loneliness scale. The vast

majority of papers that measured loneliness or social

isolation directly used survey questions using Likert

Scales or specific protocols (e.g., UCLA or De Jong

Gierveld scales). Those papers that did not use

established measures did so primarily due to an

inductive or exploratory qualitative focus, or because

of emphasis on intervention development (e.g. use of

robots) rather than intervention assessment.

A striking feature of the corpus is that two specific

demographics dominate the empirical work (the

elderly – 19 papers; and student populations – 9

papers). Such is their emphasis within the corpus that

in the following section we examine each of these

categories in turn as distinct genres. It is, however,

worth noting that this bimodal split is based upon a

priori demographic sampling decisions rather than

selections made due to indicators of loneliness or

social isolation. Most students graduate in their early

twenties, whereas retirees (particularly those in

nursing homes, a common setting of loneliness

research) normally exceed 65 years. This >40-year

gap reflects a large section of the populace absent

from research. Within the corpus 15 articles

explicitly sought to develop methods to identify

lonely or socially isolated people. 12 papers focused

explicitly on loneliness or social isolation

interventions. The remainder contained a mixture of

inductive, exploratory, and hypothetico-deductive

approaches in which loneliness or social isolation

featured.

In the following section, we describe genres

resulting from the analysis. Genres are structured

from clusters of research that frame problems of

loneliness, isolation, and digital technology in similar

ways. Given the recent emergence of much of the

work and the inevitable overlapping of some themes

within papers the genres should not be thought of as

internally consistent movements to which the authors

are aligned, rather the aim here is to illustrate

similarity of agendas and offer a lens through which

some of the key debates can be seen. There are five

identifiable genres within the corpus that describe all

but one paper (related to testing a loneliness scale in

Italy (Senese et al., 2020), albeit unrelated to digital

footprints); these are now discussed in turn.

Genre 1: The Elderly

18 papers contained an explicit focus on loneliness or

social isolation in the elderly, making it the largest

genre in the corpus (Broadbent et al. 2018; Eldib et

al.,2015; Yang and Bath, 2018; Pedell et al., 2010;

Baecker et al., 2014; Light et al., 2017; Zadeh et al.,

2020; Martinez et al., 2017; Austin et al., 2016; Ring

et al., 2013; Ha and Hoang, 2017; Bacciu et al., 2016;

Noguchi et al., 2018; Chang and Kalawsky, 2017;

Yoshida et al., 2018; Mulvenna et al., 2017; Petersen

et al., 2013; Waterworth et al., 2009). In these, older

people are identified as an at-risk group due to the

intersection of multiple life events - for example:

leaving the workforce through retirement; losing

family through bereavement; having children leave

home; or being forced into care homes for health

reasons. In each case, elderly people see

transformations of their social networks, losing

opportunities for meaningful social interaction. Such

features of ageing are well known; and because elderly

populations often tend to have limited geospatial

mobility and higher chances of interfacing with

medicalised settings, visibility of loneliness and

isolation is increased, allowing for more easily targeted

interventions. It is therefore understandable that this

genre also features the highest relative share of

interventions detailed within the corpus. In clinical

practice, algorithmic risk-based estimates of loneliness

in the elderly are likely to perform well, particularly

where personal data is available and where trust in the

robustness and explainability of the method can be

secured. Indeed, recent work showcases machine-

learning approaches already yielding reliable

performance (Yang and Bath, 2018). However, current

risk-based methods typically depend on presentation

or referral within a clinical setting.

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

228

Figure 1: (Left) Review Screening Process; (Right) Yearly breakdown of publications within final corpus.

Sampling issues of this nature raise concerns about

potentially under-served sub-populations (e.g., those

living alone), not evident in clinical settings; and who

may be more effectively identified via non-traditional

means (e.g., via digital footprint data).

Genre 2: The Student Experience

Academics have historically been criticised for an

overreliance on sampling students as part of

psychological and clinical research, but in this

instance, the need for research on the experience of

loneliness within student populations is of clear

relevance. Students often move cities to attend

university, with a sizeable minority moving

internationally to an unfamiliar place to live and work

amongst unfamiliar people. A range of papers use

students as an explicit empirical focus or do so

implicitly by only sampling from student populations

(Fuentes et al., 2016; Joyner et al., 2020; Zhou et al.,

2020; Zhang, 2010; Kindness et al., 2013; Lu and

Yao, 2010; Zhou et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2015; Ferrer

et al., 2020). Migration is a key cause of loneliness

for this cohort. Students can be made lonely and

isolated via their own movement, which fragments

prior social networks (in hope of the formation of new

ones), while limiting familial support structures. The

methodological tendency within this genre tends

towards consideration of online data sources useful

for identification of mental health problems, whereas

for the elderly genre research methods tend to focus

on interventions, and data generated by physical

technology in situ. Most papers in the corpus leverage

established survey measures to identify loneliness;

but only three papers seek to identify loneliness as a

dependent variable with the remainder focusing more

on interpersonal relationships and wellbeing. One

article (Zhou et al., 2020) notes, for instance that

‘Previous studies on loneliness have mainly focused

on using questionnaire-based loneliness scales, e.g.,

UCLA scale, for the measurement of loneliness.

Nevertheless, the lonely may prevent reporting their

real conditions since they are afraid of information

disclosure, discrimination, unfair treatment, thus it

makes the information accumulated by these

questionnaires unreliable.’ The challenge of reliable

sampling frames again raises the possibility to

supplement traditional approaches using alternative

health surveillance methods (particularly those that

examine social network or communication data - e.g.,

classroom collaboration network data). Incorporating

behavioural observation data with surveys is likely to

help scale prevalence estimates of loneliness across

broader populations (behavioural vs demographic

proxies) although risk-based probabilistic approaches

are better suited to population prevalence estimation

than deterministic assessments used in clinical

practice. There is likely a useful bifurcation in data

and methods used for population and individual level

assessment worthy of further inquiry, particularly due

to the sensitive nature of social network data.

Genre 3: Online Services, the Web, and Apps as

Windows into the Experience of Loneliness

A growing number of papers (Brueckner, 2020; De

Choudhury et al., 2014; Joseph et al., 2014; Weinert

et al., 2014; Jeong et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2017;

I Wandered Lonely in the Cloud: A Review of Loneliness, Social Isolation and Digital Footprint Data

229

Burke et al., 2010; Ananto and Young, 2021; Jeong et

al., 2016; Galunder et al., 2018; Pulekar and Agu,

2016; Rabani et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020; Wu et al.,

2016; Lu and Yao, 2010) draw on diverse data

sources being used from popular Web and Smart

Device applications such as (messaging, phone calls,

web browser logs, gaming, teleworking applications,

Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Grindr, and Amazon

Kindle) to explore loneliness within the respective

user populations. 7 articles in the corpus used

established survey measures, of which 5 applied the

UCLA survey. This genre is characterised by big data

and behavioural analytics approaches, with

commercial Web services often being repurposed for

prosocial reasons. For example Gao et al. (2019)

correlate usage of a dating website with loneliness

measures, regressing features engineered from

profiles, postings, and check-ins with ‘surveys [of]

psychological states by four professional

questionnaires measuring different kinds of mental

disorders: depression, loneliness, anxiety, and stress’.

Mixed method approaches of this nature, that

combine structured data (e.g. clinical surveys) with

wide-ranging and often unstructured social network

data, hold promise for prevalence risk estimates

within their user population; though are likely to

introduce potentially hidden forms of survivorship

bias that require triangulation within a broader

population before they could be validated. The

linking of social network usage (both time spent,

words/sentiments used, and people contacted) is a

common area of study amongst this genre. An

illustrative example can be seen in a study (Kaur et

al., 2020) of over 140 million tweets to analyse

personality insight, emotion, and sentiment analysis

in relation to social isolation during the pandemic.

The premise is a straightforward one: how we

describe ourselves and who we interact with is liable

to change throughout our lives, with such transitions

being mirrored in our digital footprints online. If this

is true, then as the authors note, aggregated results

might be used to support ‘a public health indicator to

anticipate the possibility of social isolation and design

health policies accordingly.’ However, despite

showing initial promise, further work is needed to

evaluate the efficacy of such claims, particularly

where approaches can be replicated alongside robust

clinical measures.

Genre 4: Physical Technology, Robots, and

Anthropomorphic Interactions

A series of papers (Lazányi, 2016; Eyssel and Reich,

2013; Lou et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020a; Li et al.,

2020b) focus on the creation or delivery of physical

resources, often robotic interventions, to help

alleviate social isolation and/or loneliness. The focus

of these papers is primarily development of new

technology rather than identification of loneliness.

The genre emphasises intervention (or what has been

called ‘prosocial interaction design’ – Harvey et al.,

2014), and specifically focuses on transforming the

physical environment around people likely to

experience loneliness. However, unlike interaction

design strategies that aim to pair people with other

people to foster communion and thus remove

loneliness, a far greater emphasis is placed on non-

human subjects and mastery of anthropomorphism.

The papers tend to focus on dyadic solutions to

loneliness i.e., creating a surrogate partner (either

high fidelity humanoids or non-humans such as pets

with human-like features – Lou et al., 2019) with

whom a person can form meaningful attachment.

Though Eyssel and Reich (2013) found that people

experiencing loneliness may be more likely to

anthropomorphise robots, Li et al. (2020a; 2020b)

find that the relationship is not so clear and that a

more nuanced understanding of what loneliness is can

better serve to predict efficacy of interventions,

specifically through reference to ‘trait’ versus ‘state’

loneliness. Whilst this concept - effectively

representing chronic and temporary loneliness - is not

unique in clinical literature, it is within the papers

identified within this corpus and suggests distinct data

sources could be considered for more general

measures. This genre points to the idea that

multidimensional measures of loneliness in the digital

world may help to develop subsequent interventions,

it is therefore worthy of further research, particularly

where new measures account for online experience

and can be paired with longitudinal clinical outcomes.

Genre 5: Edge Communities

The smallest identifiable genre, covering 4 papers,

considers differing edge communities - people living

in more extreme physical or mental conditions,

including refugees (Almohamed and Vyas, 2016),

mental health patients (Bearse et al., 2020), cancer

patients (Jacobs et al., 2015), ‘seafarers’, remote

communities in Greenland, and welfare claimants in

Northeast England (Jensen et al., 2020). Though these

groups represent relatively small sub-sets of the

broader population, they each nonetheless exhibit

distinct behavioural characteristics which might

prove useful in 1. generalized identification; and 2.

understanding variance across sub-populations. All

are characterised by transience i.e., people not

expected to remain a in lonely state in the long term.

They are, as Jensen et al. (2020) note, going through

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

230

‘digital liminal’ states and thus the data generated by

these people is likely to experience sharp phase

transitions. Given these demographics remain more

likely to experience loneliness at some point than the

general population they serve as excellent case

studies for designing health surveillance to

understand broader prevalence statistics. Further

research is required to identify how digital footprints

align across liminal populations and whether

metadata can be ethically obtained, especially given

the precarious lives these groups experience.

3.1 Epistemological and

Methodological Tensions

Tension 1 - Sampling and Exclusion: As noted

earlier, research into loneliness and social isolation

has to date heavily emphasised student and elderly

populations. Some exceptions exist, but children and

those in the range 21-60 have seldom been considered

as research subjects for digital footprints and

loneliness – a clear gap in the domain, made all-the-

more pressing due to changes in daily working

environments since COVID-19. Such an omission is

partly for good reason: students and the elderly are

stable populations, relatively accessible, and with

well reported challenges. Nonetheless, the corpus

excludes a huge portion of the average human life

course. Loneliness and social isolation do not, of

course, act across such neat demographics in practice.

A solution may be to develop encompassing

prevalence estimates derived from digital footprint

data.

Tension 2- Validity of Loneliness Measures: The

use of traditional scales, for example the UCLA or De

Jong Grieveld scales, may be anachronistic with the

forms of loneliness and social isolation occurring in

the modern world. Digital technology is enabling new

forms of rich and multi-faceted communication that

do not depend on being in the same place at the same

time. While the number of “contacts” we maintain has

increased due to technological innovations, has this

impacted on the shared social experience that

prevents loneliness? And is this divergence between

isolation and loneliness represented in the metrics

currently used? As most influential scales were

created prior to widespread Internet and smartphone

adoption they have little to say about the aspects of

social life now integral to work, play, and

socialisation. The notion of mixed modalities of

loneliness is something many authors note, but it is

rarely studied due to the absence of standardised

measures.

Tension 3 – Clinical versus Non-clinical

Populations and Non-overlapping Data Sets: This

tension is best illustrated by the contrast between

genre 1 (the elderly) and genre 3 (online services and

their associated big data). In the former, researchers

have excellent access to a population known to be

more likely lonely and who also likely frequent

clinical settings. This demographic is therefore easier

to identify through formal methods, but they are

likely to have sparser digital footprints when

compared with the broader populace that could be

used for prevalence estimates. In contrast, online

services such as social media have rich behavioural

data illustrative of the interactions of lonely people

and often these data cut across multiple demographics

but pairing clinical measures is harder from a

methodological and ethical perspective. Here, again

care must still be taken to avoid exclusionary bias.

Machine learning models retain biases inherent to the

datasets they are trained with - and the availability of

digital footprint data (or lack thereof) in

representative communities such as the elderly must

be considered. As such hybrid approaches seem a

sensible solution – there is no one size fits all.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Via this scoping review, several tensions, research

gaps and opportunities have been evidenced.

Unexpectedly, it is gaps in the current literature, that

potentially offer the most insight, indicating the

impact digital footprints might have in improving

loneliness prevalence estimation and modernizing its

characterization. If leveraged responsibly,

behavioural datasets promise to advance

understanding for public health and policy and help

augment a domain that has historically been forced to

rely on coarse proxy data such as age and general or

limited clinical records. Social network, mobility, and

behavioral data all hold potential to support more-

encompassing prevalence statistics of loneliness. Yet

our scoping analysis highlights several challenges

and tensions therein, issues that require continued

scholarly attention. The following opportunities, if

invested in, may help attend to these challenges,

consolidate knowledge and advance maturity in the

field:

Opportunity 1 – Sampling - The Need for

Longitudinal Study through the Life Course: To

make use of digital footprints researchers need to

ensure validity and efficacy, through ‘ground truths’

- labelling of loneliness in individuals, that can be

I Wandered Lonely in the Cloud: A Review of Loneliness, Social Isolation and Digital Footprint Data

231

paired to rich, observed behavioural data to determine

both indicators and antecedents. This is especially

relevant for middle-aged populations, who occur far

less in clinical contact records. Furthermore, inter-

and intra- person reliability measurements for

loneliness surveys are rarely conducted yet would be

highly valuable when pairing longitudinal digital

footprints for the purpose of identification and risk-

based prevalence estimates.

Opportunity 2 – Validity - Studying Digital

Loneliness as its Own Experience: distinct from the

loneliness measured and identified via surveys such

as the UCLA, the field should encourage research of

extended multi-dimensional measures and

identification tools to recognise new experiences

across mixed modalities. Our contact lists are ever

extending – however it is a lack of socially-shared

interactions which may be at the root of modern

experiences of loneliness.

Opportunity 3 – Make Data Useful, Open and

Transparent: As evidenced in Genre 3, much of the

data being studied by researchers is proprietary,

closed, and often commercial in nature.

Notwithstanding privacy concerns the need for open

data is a pre-requisite if the field is to develop. In

addition, only 3 papers include any spatial data, this

is surprisingly low because mobility/movement

tracking is often cited as a solution for loneliness

monitoring (particularly in the elderly). Broader

engagement of relevant communities, co-creation of

research studies, and focus on initiatives that engage

sufferers through open and transparent data sharing,

are required not only if we are to model loneliness

effectively – but if we are to generate practical

interventions from model explanations, with real-

world impact. Kurt Vonnegut once reportedly said

‘What should young people do with their lives today?

Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is

to create stable communities in which the terrible

disease of loneliness can be cured.’ To this we might

add, identifying and supporting those in need is a first

key step.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article is dedicated to the memory of the primary

author who sadly died near completion of the

manuscript. Dr Reedman-Flint was supported by the

Horizon Centre for Doctoral Training at the

University of Nottingham (UKRI Grant No.

EP/L015463/1)

REFERENCES

Almohamed, A., & Vyas, D. (2016). Designing for the

Marginalized: A step towards understanding the lives

of refugees and asylum seekers. In Proceedings of the

2016 acm conference companion publication on

designing interactive systems (pp. 165-168).

Ananto, R. A., & Young, J. E. (2021). We can do better! an

initial survey highlighting an opportunity for more HRI

Work on loneliness. In Companion of the 2021

ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot

Interaction (pp. 457-462).

Austin, J., Dodge, H. H., Riley, T., Jacobs, P. G., Thielke,

S., & Kaye, J. (2016) A smart-home system to

unobtrusively and continuously assess loneliness in

older adults. IEEE journal of translational engineering

in health and medicine, 4, 1-11.

Baecker, R., Sellen, K., Crosskey, S., Boscart, V., &

Barbosa Neves, B. (2014). Technology to reduce social

isolation and loneliness. In Proceedings of the 16th

international ACM SIGACCESS conference on

Computers & accessibility (pp. 27-34).

Bacciu, D., Chessa, S., Ferro, E., Fortunati, L., Gallicchio,

C., La Rosa, D., ... & Vozzi, F. (2016). Detecting

socialization events in ageing people: The experience

of the doremi project. In 2016 12th International

Conference on Intelligent Environments (IE) (pp. 132-

135). IEEE

BBC (2019) BBC Radio 4 - The Anatomy Of Loneliness -

Who Feels Lonely? [Online] Available at:

https://bbc.in/3NOjIey [Accessed 15 May 2021].

Bearse, P., Manejwala, O., Mohammad, A. F., & Haque, I.

R. I. (2020). An Initial Feasibility Study to Identify

Loneliness Among Mental Health Patients from

Clinical Notes. In 2020 3rd International Conference on

Information and Computer Technologies (ICICT) (pp.

68-77). IEEE.

Broadbent, E., Ahn, H. S., Kerse, N., Peri, K., Sutherland,

C., Law, M., ... & Pandey, A. K. (2018). Can robots

improve the quality of life in people with dementia?. In

Proceedings of the Technology, Mind, and Society (pp.

1-3).

Brueckner, S. (2020). Captured by an Algorithm. In ACM

SIGGRAPH 2020 Art Gallery (pp. 458-459).

Bu, F., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Who is lonely

in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of

loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Public Health, 186, 31-34.

Burke, M., Marlow, C., & Lento, T. (2010). Social network

activity and social well-being. In Proceedings of the

SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing

systems (pp. 1909-1912).

Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human

nature and the need for social connection. WW Norton

& Company.

Chang, A. S., & Kalawsky, R. S. (2017). Future

configurable transport for the ageing population. In

2017 7th International Conference on Power

Electronics Systems and Applications-Smart Mobility,

Power Transfer & Security (PESA) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

232

De Choudhury, M., Counts, S., Horvitz, E. J., & Hoff, A.

(2014). Characterizing and predicting postpartum

depression from shared facebook data. In Proceedings

of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported

cooperative work & social computing (pp. 626-638).

de Jong-Gierveld, J. (1987). Developing and testing a

model of loneliness. Journal of personality and social

psychology, 53(1), 119.

DiTommaso, E., & Spinner, B. (1993). The development

and initial validation of the Social and Emotional

Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA). Personality and

individual differences, 14(1), 127-134.

Dunbar, R., 2021. Friends: Understanding the power of our

most important relationships. Hachette UK.

Eldib, M., Deboeverie, F., Haerenborgh, D. V., Philips, W.,

& Aghajan, H. (2015). Detection of visitors in elderly

care using a low-resolution visual sensor network. In

Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on

Distributed Smart Cameras (pp. 56-61).

Elovainio, M., Hakulinen, C., Pulkki-Råback, L., Virtanen,

M., Josefsson, K., Jokela, M., ... & Kivimäki, M.

(2017). Contribution of risk factors to excess mortality

in isolated and lonely individuals: an analysis of data

from the UK Biobank cohort study. The Lancet Public

Health, 2(6), e260-e266.

Ernst, M., Niederer, D., Werner, A. M., Czaja, S. J., Mikton,

C., Ong, A. D., ... & Beutel, M. E. (2022). Loneliness

before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A

systematic review with meta-analysis. American

Psychologist.

Eyssel, F., & Reich, N. (2013). Loneliness makes the heart

grow fonder (of robots)—On the effects of loneliness

on psychological anthropomorphism. In 2013 8th

acm/ieee international conference on human-robot

interaction (hri) (pp. 121-122). IEEE.

Ferrer, M., Mancha, V., Chumpitaz, M., Begazo, J., &

Chauca, M. (2020). Characterization of the impact of

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic social isolation on the

psychosocial well-being of public university students,

based on the GHQ-28 Scale. In Proceedings of the 4th

International Conference on Medical and Health

Informatics (pp. 295-301).

Fuentes, C., Rodríguez, I., & Herskovic, V. (2016). Making

Communication Frequency Tangible: How Green Is

My Tree?. In Proceedings of the TEI'16: Tenth

International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and

Embodied Interaction (pp. 434-440).

Galunder, S. S., Gottlieb, J. F., Ladwig, J., Hamell, J.,

Keller, P. K., & Wu, P. (2018). A VR ecosystem for

telemedicine and non-intrusive cognitive and affective

assessment. In 2018 IEEE 6th International Conference

on Serious Games and Applications for Health

(SeGAH) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Gao, X., Zhang, C., Ma, L., Wang, Y., Wang, J., & Zhang,

D. (2019). Correlating msm's mental health with usage

behaviors on msm-specific social applications. In 2019

IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence &

Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computing, Scalable

Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data

Computing, Internet of People and Smart City

Innovation IEEE.

Griffin, J. (2010). The lonely society?. Mental Health

Foundation.

Ha, T. V., & Hoang, D. B. (2017). An assistive healthcare

platform for both social and service networking for

engaging elderly people. In 2017 23rd Asia-Pacific

Conference on Communications (APCC) (pp. 1-6).

IEEE.

Harvey, J., Golightly, D., & Smith, A. (2014). HCI as a

means to prosociality in the economy. In Proceedings

of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems (pp. 2955-2964).

Hertz, N. (2021). The lonely century: how to restore human

connection in a world that's pulling apart. Currency.

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2017). The potential public health

relevance of social isolation and loneliness: Prevalence,

epidemiology, and risk factors. Public Policy & Aging

Report, 27(4), 127-130.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010).

Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic

review. PLoS medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

Ibarra, F., Baez, M., Cernuzzi, L., & Casati, F. (2020). A

systematic review on technology-supported

interventions to improve old-age social wellbeing:

loneliness, social isolation, and connectedness. Journal

of healthcare engineering, 2020.

Jacobs, M. L., Clawson, J., & Mynatt, E. D. (2015).

Comparing health information sharing preferences of

cancer patients, doctors, and navigators. In Proceedings

of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported

Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 808-818).

Jensen, R. B., Coles-Kemp, L., Wendt, N., & Lewis, M.

(2020). Digital liminalities: Understanding isolated

communities on the edge. In Proceedings of the 2020

CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems (pp. 1-14).

Jeong, E. J., Kim, D. J., & Lee, D. M. (2015). Game

addiction from psychosocial health perspective. In

Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on

Electronic Commerce 2015 (pp. 1-9).

Jeong, E. J., Kim, D. J., Lee, D. M., & Lee, H. R. (2016). A

study of digital game addiction from aggression,

loneliness and depression perspectives. In 2016 49Th

Hawaii International Conference On System Sciences

(HICSS) (pp. 3769-3780). IEEE.

Joseph, K., Carley, K. M., & Hong, J. I. (2014). Check-ins

in “Blau Space” Applying Blau’s Macrosociological

Theory to Foursquare Check-ins from New York City.

ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and

Technology (TIST), 5(3), 1-22.

Joyner, D. A., Wang, Q., Thakare, S., Jing, S., Goel, A., &

MacIntyre, B. (2020). The synchronicity paradox in

online education. In Proceedings of the Seventh ACM

Conference on Learning@ Scale (pp. 15-24).

Kaur, S., Kaul, P., & Zadeh, P. M. (2020). Study the impact

of covid-19 on twitter users with respect to social

isolation. In 2020 Seventh International Conference on

Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security

(SNAMS) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

I Wandered Lonely in the Cloud: A Review of Loneliness, Social Isolation and Digital Footprint Data

233

Kindness, P., Mellish, C., & Masthoff, J. (2013). How

virtual teammate support types affect stress. In 2013

Humaine Association Conference on Affective

Computing and Intelligent Interaction (pp. 300-305).

IEEE.

Knox, S. S., & Uvnäs-Moberg, K. (1998). Social isolation

and cardiovascular disease: an atherosclerotic

pathway?. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 23(8), 877-890.

Lazányi, K. (2016). Investing in social support—Robots as

perfect partners?. In 2016 IEEE 14th International

Symposium on Intelligent Systems and Informatics

(SISY) (pp. 25-30). IEEE.

Li, S., Ni, S., & Peng, K. (2020a). The Role of Good Human

Uniqueness in Social Robot Anthropomorphism

Influenced by Chronic Loneliness. In 2020 IEEE

International Conference on Human-Machine Systems

(ICHMS) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Li, S., Xu, L., Yu, F., & Peng, K. (2020b). Does trait

loneliness predict rejection of social robots? In

Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International

Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (pp. 271-

280).

Light, A., Howland, K., Hamilton, T., & Harley, D. A.

(2017). The meaing of place in supporting sociality. In

Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Designing

Interactive Systems (pp. 1141-1152).

Lu, X., & Yao, J. (2010). The Influence of Internet

Interpersonal Communication to Relationship and

Loneliness of College Students. In 2010 International

Conference on Web Information Systems and Mining

(Vol. 2, pp. 386-390). IEEE.

Lou, C., Zhao, J., Li, X., Wei, H., Zhang, Y., & Zhao, H.

(2019). Pet Robot Emotional Interaction for Urban

Autism. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International

Conference on Intelligent Science and Technology (pp.

1-6).

Lubben, J. (2017). Addressing social isolation as a potent

killer!. Public Policy & Aging Report, 27(4), 136-138.

Marangoni, C., & Ickes, W. (1989). Loneliness: A

theoretical review with implications for measurement.

Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 6(1), 93-

128.

Martinez, A., Ortiz, V., Estrada, H., & Gonzalez, M. (2017)

A predictive model for automatic detection of social

isolation in older adults. In 2017 International

Conference on Intelligent Environments (IE) (pp. 68-

75). IEEE.

Matthews, T., Danese, A., Wertz, J., Odgers, C. L., Ambler,

A., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2016). Social

isolation, loneliness and depression in young

adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Social

psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 51(3), 339-

348.

Mulvenna, M., Zheng, H., Bond, R., McAllister, P., Wang,

H., & Riestra, R. (2017). Participatory design-based

requirements elicitation involving people living with

dementia towards a home-based platform to monitor

emotional wellbeing. In 2017 IEEE International

Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine

(BIBM) (pp. 2026-2030). IEEE.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur,

A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or

scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing

between a systematic or scoping review approach.

BMC medical research methodology, 18(1), 1-7.

Noguchi, Y., Kamide, H., & Tanaka, F. (2018). Effects on

the self-disclosure of elderly people by using a robot

which intermediates remote communication. In 2018

27th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and

Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) (pp.

612-617). IEEE.

ONS (2018) Loneliness [Online] available at:

https://bit.ly/3zd10ZL [Accessed 15 May 2021]

Pedell, S., Vetere, F., Kulik, L., Ozanne, E., & Gruner, A.

(2010). Social isolation of older people: the role of

domestic technologies. In Proceedings of the 22nd

Conference of the Computer-Human Interaction

Special Interest Group of Australia on Computer-

Human Interaction (pp. 164-167).

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social

psychology of loneliness. Personal relationships, 3, 31-

56.

Petersen, J., Austin, D., Kaye, J. A., Pavel, M., & Hayes, T.

L. (2013). Unobtrusive in-home detection of time spent

out-of-home with applications to loneliness and

physical activity. IEEE journal of biomedical and

health informatics, 18(5), 1590-1596.

Pulekar, G., & Agu, E. (2016). Autonomously sensing

loneliness and its interactions with personality traits

using smartphones. In 2016 IEEE healthcare innovation

point-of-care technologies conference (HI-POCT) (pp.

134-137). IEEE.

Rabani, S. T., Khan, Q. R., & Khanday, A. M. U. D. (2020).

Multi-Class Suicide Risk Prediction on Twitter Using

Machine Learning Techniques. In 2020 2nd

International Conference on Advances in Computing,

Communication Control and Networking (ICACCCN)

(pp. 128-134). IEEE.

Ring, L., Barry, B., Totzke, K., & Bickmore, T. (2013)

Addressing loneliness and isolation in older adults:

Proactive affective agents provide better support. In

2013 Humaine Association conference on affective

computing and intelligent interaction (pp. 61-66).

IEEE.

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3):

Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of

personality assessment, 66(1), 20-40.

Russell, D., Cutrona, C. E., Rose, J., & Yurko, K. (1984).

Social and emotional loneliness: an examination of

Weiss's typology of loneliness. Journal of personality

and social psychology, 46(6), 1313.

Scalise, J. J., Ginter, E. J., & Gerstein, L. H. (1984).

Multidimensional loneliness measure: the loneliness

rating scale (LRS). Journal of Personality Assessment,

48(5), 525-530.

Schmidt, N., & Sermat, V. (1983). Measuring loneliness in

different relationships. Journal of personality and social

psychology, 44(5), 1038.

Senese, V. P., Nasti, C., Mottola, F., Sergi, I., & Gnisci, A.

(2020, September). Validation and measurement

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

234

invariance across gender and age of the Italian

Interpersonal Acceptance-Rejection Loneliness Scale.

In 2020 11th IEEE International Conference on

Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom) (pp.

000289-000294). IEEE

Shah, S. G. S., Nogueras, D., Van Woerden, H., &

Kiparoglou, V. (2019). Effectiveness of digital

technology interventions to reduce loneliness in adults:

a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMJ open, 9(9), e032455.

Steptoe, A., Shankar, A., Demakakos, P., & Wardle, J.

(2013). Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause

mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5797-5801.

Taylor, S. H., Hutson, J. A., & Alicea, T. R. (2017). Social

consequences of Grindr use: Extending the internet-

enhanced self-disclosure hypothesis. In Proceedings of

the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems (pp. 6645-6657).

Waterworth, J. A., Ballesteros, S., & Peter, C. (2009). User-

sensitive home-based systems for successful ageing. In

2009 2nd Conference on Human System Interactions

(pp. 542-545). IEEE.

Weil, S. (1997). Gravity and grace. U of Nebraska Press

Weinert, C., Maier, C., Laumer, S., & Weitzel, T. (2014).

Does teleworking negatively influence IT

professionals? An empirical analysis of IT personnel's

telework-enabled stress. In Proceedings of the 52nd

ACM conference on Computers and people research

(pp. 139-147).

Weiss, R. (1975). Loneliness: The experience of emotional

and social isolation. MIT press.

Wu, Y., Yuan, J., You, Q., & Luo, J. (2016). The effect of

pets on happiness: A data-driven approach via large-

scale social media. In 2016 IEEE International

Conference on Big Data (Big Data) (pp. 1889-1894).

IEEE.

Xu, D., Qian, L., Wang, Y., Wang, M., Shen, C., Zhang, T.,

& Zhang, J. (2015). Understanding the dynamic

relationships among interpersonal personality

characteristics, loneliness, and smart-phone use:

evidence from experience sampling. In 2015

International Conference on Computer Science and

Mechanical Automation (CSMA) (pp. 19-24). IEEE.

Yang, H., & Bath, P. A. (2018). Prediction of Loneliness in

Older People. In Proceedings of the 2nd International

Conference on Medical and Health Informatics (pp.

165-172).

Yoshida, M., Kleisarchaki, S., Gtirgen, L., & Nishi, H.

(2018). Indoor occupancy estimation via location-

aware HMM: An IoT approach. In 2018 IEEE 19th

International Symposium on" A World of Wireless,

Mobile and Multimedia Networks"(WoWMoM) (pp.

14-19). IEEE.

Zadeh, P. M., Khani, S., Pfaff, K., & Samet, S. (2020). A

computational model and algorithm to identify social

isolation in elderly population. In 2020 IEEE

Symposium on Computers and Communications

(ISCC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Zhang, M. (2010). Exploring adolescent peer relationships

online and offline: an empirical and social network

analysis. In 2009 WRI International Conference on

Communications and Mobile Computing (Vol. 3, pp.

268-272). IEEE.

Zhou, Z., Sun, X., Chen, X., Fan, C., & Pan, Q. (2009). The

Relation between Different Constructs in Middle

Childhood Peer Interaction and Loneliness: A

Mediational Model. In 2009 3rd International

Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical

Engineering (pp. 1-4). IEEE.

Zhou, Q., Li, J., Tang, Y., & Wang, H. (2020). Discovering

the Lonely Among the Students with Weighted Graph

Neural Networks. In 2020 IEEE 32nd International

Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence

(ICTAI) (pp. 474-481). IEEE.

I Wandered Lonely in the Cloud: A Review of Loneliness, Social Isolation and Digital Footprint Data

235