Innovation in Boutique Hotels in Valletta, Malta:

A Multi-level Investigation

Kristina Buhagiar

a

The Edward de Bono Institute for Creative Thinking and Innovation,

University of Malta, Msida, Malta

Keywords: Service Innovation, Knowledge Resources, Dynamic Capabilities, Microfoundations, Boutique Hotels.

Abstract: Service innovation has come to reflect a multidimensional and fuzzy construct defined by elusiveness. As

such, the terminology ‘service innovation’, while increasingly important in servitized and experience-based

economies, has come to denote ‘everything and nothing at the same time’. Further amplifying these issues,

scholars remain divided on whether service innovation should be explored from a demarcation, synthesis, or

assimilation approach, while service innovation process models provide overly simplified representations of

the service innovation process. To counteract these shortfalls, and based on Buhagiar et al.’s (2021)

conceptual multi-level model of service innovation, this paper, through the application of a qualitative

methodology, explores the service innovation process of boutique hotels located in Valletta, Malta. The results

of this study explicate that knowledge resources and the capacity of personnel in boutique hotels to combine

and transform knowledge resources, at both the micro-level and firm-level, mirror core capabilities

necessitated to develop innovation in boutique hotels. Furthermore, service innovation emerged as a human-

centric process, with idea generation inherently contingent on the cognitive capacities of personnel in boutique

hotels. Thus, inciting the innovation process in boutique hotels emerged as contingent and path-dependent on

the motivations of personnel to identify innovation opportunities, and externalize subjective tacit knowledge.

1 INTRODUCTION

Globally, service economies have been

acknowledged to dominate in terms of output,

employment and value added (Buckley &

Majumdar, 2018). For example, in Malta, in 2021,

services accounted for 77.44% of the economy

(Statista, 2022). However, despite the increasing

growth and importance of the service economy, the

literature on service innovation theory has been

critiqued for insufficiently addressing the notion of

the service innovation process (Snyder et al., 2016;

Witell et al., 2016). As a result, the resources and

processes through which service organizations

innovate remains elusive and subject to numerous

conceptualizations.

Based on Buhagiar et al.’s (2021) conceptual

model, this paper presents the results obtained from

a qualitative investigation conducted on boutique

hotels in Valletta, Malta. The results presented in

this study address the service innovation process of

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1484-2781

boutique hotels in Valletta, Malta by outlining the

micro-foundation processes and firm-level

capabilities hotel owners and managers/supervisors

were found to implement to give rise to innovation

activities.

This paper is structured to cover six core sections.

Following this introduction, Section 2 presents the

theoretical background, here the literature

associated with service innovation theory is

discussed and the gaps present in the literature are

outlined. Building on these gaps, Section 3 outlines

the methodological underpinnings employed to

explore Buhagiar et al.’s (2021) conceptual model.

Section 4 presents the results which emerged from

the empirical investigation. Section 5 discusses the

implications of this research, and Section 6 presents

the conclusions and limitations of this study.

Buhagiar, K.

Innovation in Boutique Hotels in Valletta, Malta: A Multi-level Investigation.

DOI: 10.5220/0011585500003335

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2022) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 95-106

ISBN: 978-989-758-614-9; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

95

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

2.1 Service Innovation

Service innovation has been conceptualized to mirror

a fuzzy and complex multi-phase process, that is

iterative in nature and structurally fluid (Chesbrough,

2017; Engen & Magnusson, 2018; Lusch & Vargo,

2018; Song et al., 2009; Toivonen & Tuominen,

2009; Xu & Wang, 2020). As the literature in service

innovation theory advances (see, for example,

Gallouj & Savona, 2009; Singh et al., 2020; Snyder et

al., 2016; Witell et al., 2016), service innovation has

come to reflect a multifaceted construct, with

theoretical contributions generally positioning this

form of innovation to represent a panoptic

terminology, i.e., an all-encompassing theoretical

standpoint (Carlborg et al., 2014).

Despite the exhaustive connotation generally

associated with the term ‘service innovation’, recent

scholarly efforts define this form of innovation as “a

new process or offering that is put into practice and is

adopted by and creates value for one or more

stakeholders” (Gustafsson et al., 2020, p. 114).

Similarly, the literature in service innovation theory

also converges on particular attributes positioned as

central to the notion of service innovation.

In this respect, service innovation has come to

reflect a process defined by resource combinations

(Song et al, 2009; Sundbo 1997, 2009; Toivonen &

Tuominen, 2009), with intra- and inter-organizational

knowledge resources positioned as fundamental to

the service innovation process (Galanakis, 2006;

Peschl & Fundneider, 2014; Nonaka & Takeuchi,

2019). From this perspective, “when organizations

innovate, they do not simply process information. . . .

They actually create new knowledge and information”

(Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995, p. 56), therefore, “a

highly complex knowledge process can be found to

be at the root of every innovation” (Peschl &

Fundneider, 2014, p. 347). Thus, service innovation

is generally conceptualized to be grounded in

combinations and re-combinations of knowledge

resources (Lusch & Nambisan, 2015), representing a

living, dynamic, and evolutionary input to the service

innovation process.

To acquire the knowledge resources necessitated

for the service innovation process, service

organizations generally rely on knowledge exchanges

with key intra- and inter-organizational members,

including ecosystem actors (Hidalgo & D’Alvano,

2014; Lusch & Vargo, 2018), customers (Li & Hsu,

2016; Xu & Wang, 2020), and intra-organizational

personnel, being employees (Engen & Magnusson,

2018), managers (Tidd & Bessant, 2014), and owners

(Crossan & Berdow, 2003; Camisón et al., 2020). At

an ecosystem level, market actors contribute towards

service innovation by way of collaborative value

creation, with operant resources, i.e., knowledge

resources, flowing bi-directionally in the ecosystem

(Buhagiar, 2021; Lusch & Vargo, 2018), leading to

decentralized forms of innovation, i.e., open

innovation (Chesbrough, 2017). Similarly, in the

service innovation process, whether directly or

indirectly, customers contribute towards service

innovation by way of providing service organizations

with suggestions for improvement (Li & Hsu, 2016;

Xu & Wang, 2020), or by acting as an impetus or a

source of inspiration for change (Duverger, 2012).

Therefore, in service innovation, “customers are thus

no longer regarded as inert targets of the value

proposition but are rather coproducers of the value

they buy” (Espejo & Dominici, 2017, p. 25).

Moreover, similar to an autopoietic system,

service organizations are capable of generating

innovations in a self-referential manner through

combinations of knowledge resources from intra-

organizational personnel. For example, employees

may either lead the innovation process via the

proactive identification of innovation opportunities

and the development of novel ideas, or through

supporting innovation activities by reporting

problems (Engen & Magusson, 2018). Similarly,

managers, while responsible for generating ideas,

may simultaneously be tasked with establishing a

culture and climate for innovation through leading,

structuring, and guiding innovation activities (Tidd &

Bessant, 2014). In the service innovation process, the

decision-making rights, authority, and the capacity of

owners to allocate resources to innovations have also

been reported to exert an influence on the nature and

the scope of service innovations (Gutierrez et al.,

2008; Camisón-Zornoza et al., 2020).

With service innovation contingent on resource

combinations from both intra- and inter-organization

actors, service organizations follow an autopoietic

form of organization, which refers to “processes

interlaced in the specific form of a network of

productions of components which realizing the

network that produce them constitute it as a unity”

(Varela & Maturana, 1980). Due to the dependence

of service organizations on resource combinations

from both inter- and intra-organizational actors to

effectuate service innovation, innovation in this

context may occur in a systematic or unsystematic

manner (Song et al., 2009; Toivonen & Tuominen,

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

96

2009), while the boundaries between a service

organization and the external environment may

increasingly appear blurred (Chesbrough, 2017). In

terms of the degrees of novelty a service innovation

may invoke, these range from radical to incremental

(Binder et al., 2016) and, simultaneously, the

multidimensional nature of service innovation sees

this construct manifest in four core dimensions,

including service concept innovation, client interface

innovation, service delivery system innovation, and

information technology innovation (Miles, 2008).

Based on the nuanced and convoluted attributes

comprising service innovation, Witell et al. (2016)

asserted that “lack of precision in the service

innovation concept makes it ambiguous” (p. 2870),

while diverging theoretical positions and the added

complexities of the assimilation, demarcation, and

synthesis approaches, have led to an overarching

sense of conceptual confusion in the service

innovation literature (Snyder et al., 2016; Witell et al.,

2016). Furthermore, although service innovation

process models have been developed (see, for

example, Song et al., 2009; Toivonen & Tuominen,

2009), they tend to be reductionist in nature, with

these models presenting overly simplified

illustrations of the service innovation process. In

addition, these models also omit to account for the

complex and fuzzy role of knowledge resources in

service innovation, resulting in process models which

fall short of explicating how knowledge resources are

transformed into productive resources. Compounding

these issues, Keszey (2018) stressed that “while

scholars and practitioners alike require a sound

understanding of how knowledge sharing influences

innovation outcomes to firms’ maximum

performance, empirical research on this domain

remains rather scarce” (p. 1062). Similarly, Edghiem

and Mouzughi (2018) critiqued the literature for

insufficiently addressing the implications of

knowledge resources in the service innovation

process.

To overcome the preceding shortfalls, and based

on the nascent nature of the boutique hotel sector,

where few empirical investigations have been

conducted (see, for example, Ghaderi et al., 2020;

Loureiro et al., 2019; Parolin & Boeing, 2019), this

study sought to investigate service innovation in

boutique hotels located in Valletta, Malta through

exploring three research questions (RQ), including:

RQ1: How does innovation develop in boutique

hotels in Valletta, Malta through knowledge

resources?

RQ2: What is the structure and the nature of the

innovation process in boutique hotels in Valletta,

Malta?

RQ3: What is the role of knowledge reconfiguration

capabilities in the innovation process of boutique

hotels in Valletta, Malta?

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Conceptual Model & Philosophical

Underpinnings

To investigate the three research questions presented

in Section 2 above, Buhagiar et al.’s (2021)

conceptual multi-level model rooted in the

knowledge-based view (Grant, 1996), Nonaka’s

(1994) dynamic theory of organizational knowledge

creation, and the dynamic capabilities approach

(Teece et al., 1997) was applied in this investigation.

Moreover, due to the prevalent positivist approach

adopted by scholars in the tourism literature to

investigate the link between knowledge resources and

service innovation (see, for example, Nordli, 2018;

Pongsathornwiwat et al., 2019; Thomas & Wood,

2014), the philosophical underpinnings applied in this

research comprised a constructivist interpretive

paradigm. This paradigm was selected as: 1) it is able

to account for and accentuate the human-centric,

complex, and iterative nature generally necessitated

to transform knowledge resources into innovation

(Nonaka, 1994), and 2) enable a holistic perspective

of service innovation to emerge.

3.2 Data Collection Technique

Based on the principles underpinning the

constructivist paradigm, this research applied a

qualitative methodology to capture and account for

the unique, personal, and subjective perspectives of

interview respondents when discussing the service

innovation process.

In this study, data collection was effectuated

through semi-structured interviews with boutique

hotel owners and managers/supervisors. The

interview template used to guide semi-structured

interviews comprised 36 questions, with questions

structured to collect data on six core themes,

including 1) demographic data/background

information, 2) the innovation process when

establishing boutique hotels, 3) environmental

dynamics prior to and during Covid-19, 4) the role of

Innovation in Boutique Hotels in Valletta, Malta: A Multi-level Investigation

97

knowledge resources in the innovation process, 5) the

innovation process prior to Covid-19, and 6) the

innovation process during Covid-19. Once interview

templates and letters of consent were drafted, these

were submitted for ethics approval. Following ethics

approval, data collection took place between 4th

August 2021 and 2nd May 2022 in Valletta, Malta.

To recruit relevant participants in this study, the

sampling techniques grounding this research

comprised both purposive sampling and convenience

sampling, with sample criteria established for 1)

boutique hotels, and 2) boutique hotel

managers/supervisors and owners.

Once a list of eligible boutique hotels and

interview respondents was established, the researcher

contacted respondents via email to ascertain their

interest in participating in this study. To further

increase the uptake of interview participants in this

study, the researcher personally visited boutique

hotels in Valletta, Malta several times. To increase

the validity and the reliability of research findings,

audio recordings were transcribed by the researcher

in-verbatim, they were sent to interview participants

for member checking, and diverging/negative cases

were reported. To analyse interview data, the

researcher applied six rounds of coding, including 1)

open coding, 2) axial coding, 3) structured coding, 4)

provisional coding, 5) causation coding and 6) the

constant comparative method.

Based on the results obtained through semi-

structured interviews, the following section, i.e.,

Section 4, discusses the core findings which emerged

through data collection and analysis efforts.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Sample Attributes

Between 4th August 2021 and 2nd May 2022, 25

interviews were conducted with both boutique hotel

owners and managers/supervisors from 14 boutique

hotels located in Valletta, Malta. Out of the 25

interviews conducted, 18 interviews were held in-

person, and 7 interviews were held virtually due to

Covid-19 restrictions. Interviews were audio

recorded and conducted in the English language, with

each interview lasting approximately 74 minutes,

while the total number of recorded minutes from

these interviews equated to 1,923.98 minutes. From

the 25 respondents who participated in this study, 9

respondents were boutique hotel owners, and 16

respondents were boutique hotel

managers/supervisors. In terms of the demographic

composition of the 25 interview respondents, the

average age of interviewees was 41 years of age, 16

respondents were male, and 9 respondents were

female. Moreover, in terms of the nationality of

interviewees, 9 respondents were foreign nationals,

and 16 respondents were Maltese nationals. Out of the

14 boutique hotels explored in this study, the

ownership structures fostered by sampled hotels

ranged from independently owned boutique hotels,

which comprised 9 hotels, to group-owned boutique

hotels, which totaled 5 hotels. Group-owned boutique

hotels were further subdivided into chain-owned

boutique hotels, which consisted of 2 hotels, and

multi-sector group-owned boutique hotels, which

comprised 3 hotels. Due to the ethical protocol

employed within this research, pseudonyms were

allocated to the boutique hotels (BH), boutique hotel

owners (BHO) and managers/supervisors (BHE)

comprising the investigated sample.

4.2 Knowledge-reconfiguration

Micro-foundation Processes

This section, i.e., Section 4.2, critically discusses the

micro-foundation processes boutique hotel

managers/supervisors and owners reported to use in

order to transform knowledge resources into

innovation.

The objectives of this section, therefore, are to

explicate the nature of the innovation process in

boutique hotels, and to unravel the role of knowledge

resources in this process. Due to the small sample size

comprising this study, the results discussed in the

following sections are not generalizable, therefore,

they are only relevant to the investigated sample.

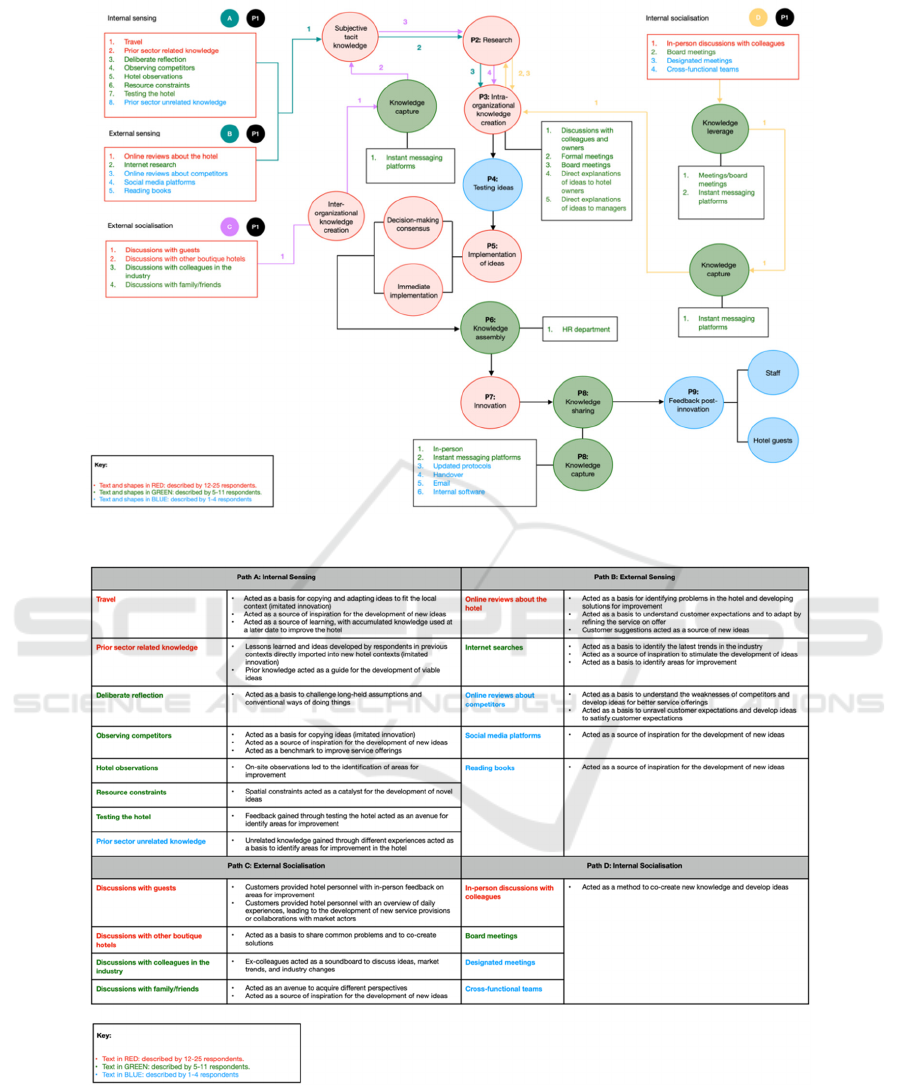

At a micro-foundation level, in the investigated

boutique hotels, the innovation process emerged to

reflect a nine-phase knowledge-based process (Figure

1), with four novel paths used by personnel in

boutique hotels to generate ideas and stimulate

innovation activities (Figure 2). While transforming

knowledge resources into innovation reflected a nine-

phases process (Figure 1), the uptake and the

implementation of each micro-foundation process in

boutique hotels varied, with processes 1 (idea

generation), 2 (research), 3 (intra-organizational

knowledge creation), 5 (implementation of ideas),

and 7 (innovation) frequently implemented by all the

boutique hotels comprising this sample. Moderately

implemented micro-foundation processes included

processes 6 (knowledge assembly) and 8 (knowledge

sharing), while processes 4 (testing ideas) and 9

(feedback post-innovation) were subject to low

degrees of uptake in the sample comprising this study.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

98

In line with Figures 1 and 2, the innovation

process comprising boutique hotels mirrored a

complex, nuanced, and highly personal process, with

personnel in boutique hotels using multiple

heterogeneous sources of both tacit and explicit

knowledge to catalyze idea generation activities.

With four novel paths used by personnel in boutique

hotels to generate ideas, the start of the innovation

process reflects a subjective and personal process,

which may be invoked by numerous stimuli, and

which may evolve in a sporadic and unprecedented

manner. The nuanced nature of the innovation

process comprising boutique hotels was also mirrored

in phase 3, i.e., knowledge creation activities, with the

externalization of tacit knowledge occurring through

numerous different methods and contextual

structures, e.g., discussions with colleagues and

owners, formal meetings, board meetings, etc., this

indicates that knowledge creation in boutique hotels

reflects a context-dependent process influenced by

institutional routines and tacitly embedded norms.

While micro-foundation phases 1 to 3 of the

innovation process reflected highly personal

knowledge-based processes contingent on the

individual efforts of the personnel comprising

boutique hotels, phases 4 to 9 mirrored comparatively

linear and impersonal processes.

When exploring the innovation processes of

boutique hotels by different ownership structures

(independently owned boutique hotels, chain-owned

boutique hotels, and multi-sector group-owned

boutique hotels), the results of this study revealed that

multi-sector group-owned boutique hotels possessed

the longest and the most thorough innovation process,

with personnel from these hotels implementing all 9

micro-foundation processes to reconfigure

knowledge resources and develop innovation.

Independently owned boutique hotels also comprised

a relatively long innovation cycle, with personnel

from these hotels implementing 8 micro-foundation

processes to reconfigure knowledge resources and

develop innovation. Personnel from independently

owned boutique hotels did not report any processes to

assemble knowledge resources (process 6). Chain-

owned boutique hotels comprised the shortest

innovation cycle, with personnel from these hotels

implementing 6 micro-foundation processes to

reconfigure knowledge resources and establish

innovation. In addition to comprising the shortest

innovation cycle, personnel from these hotels did not

report implementing micro-foundation processes 4

(testing ideas), 6 (knowledge assembly), and 9

(feedback post-innovation).

Based on the 25 interviews conducted with

boutique hotel owners and managers/supervisors, in

this research, innovation emerged to reflect a human-

centric, and complex process rooted in knowledge

resources. As the core productive resource grounding

the innovation process in boutique hotels,

idiosyncratic sequences of tacit and explicit

knowledge resources were combined and recombined

by interviewees to identify innovation opportunities,

with idea generation processes in these

accommodation provisions aligning to the principles

of equifinality, and evolving in a seemingly

unstructured manner. In and of itself, this finding

indicates that generating ideas in boutique hotels, and

therefore, catalyzing the innovation process, is

contingent on both the cognitive capacities of

boutique hotel owners and managers/supervisors, as

well as their willingness to externalize and share their

subjective tacit knowledge with other personnel in

boutique hotels.

Further compounding the complexity and the

unique nature of the innovation process in boutique

hotels, ownership structures were also found to exert

an impact on the number of micro-foundation

processes used in boutique hotels. In this respect,

multi-sector group-owned boutique hotels possessed

the longest innovation cycle, with formalized

structures specifically established by these hotels to

leverage and create knowledge. Independently owned

boutique hotels comprised an 8 phase micro-

foundation process, with these hotels neglecting to

implement knowledge assembly practices. In itself,

this finding indicates that while independently owned

boutique hotels relied on knowledge resources to

generate ideas, these hotels did not comprise the

structures or knowledge bases necessary to establish

innovations of a technical nature. Chain-owned

boutique hotels possessed the shortest innovation

cycle, with these hotels lacking the necessary

structures to establish innovations of a technical

nature, while simultaneously neglecting to validate

ideas and gauge innovation post-implementation.

Further extending the preceding results, Section

4.3 discusses the role of firm-level capabilities for

reconfiguring knowledge resources in the innovation

process comprising boutique hotels.

Innovation in Boutique Hotels in Valletta, Malta: A Multi-level Investigation

99

Figure 1: Micro-Foundation Knowledge Processes Implemented in Boutique Hotels in Valletta, Malta.

Figure 2: Idea Generation Processes in Boutique Hotels in Valletta, Malta.

4.3 Knowledge-reconfiguration

Capabilities

In line with Figure 3 below, in this study, 6 firm-level

knowledge reconfiguration capabilities were found to

be present in the boutique hotels investigated in this

research, including: 1) sensing capabilities, 2)

validation capabilities, 3) knowledge creation

capabilities, 4) seizing capabilities, 5) reconfiguration

capabilities, and 6) knowledge integration capabilities.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

100

Figure 3: Firm-level Knowledge Reconfiguration

Capabilities.

When exploring the level of routinization

comprising each firm-level capability, the results of

this study outlined that sensing capabilities largely

mirrored micro-level cognitive capabilities, with

hotels only able to establish routines for 1) evoking

discussions with hotel guests (external socialization)

(BH1, BH2, BH3, BH4, BH5, BH6, BH7, BH8, BH9,

BH10, BH11, BH12, BH13, BH14), 2) scanning

reviews about the hotel (BH1, BH2, BH3, BH4, BH5,

BH6, BH7, BH8, BH9, BH10, BH11, BH12, BH13,

BH14) and, to a lesser extent, competitors (external

sensing) (BH1, BH2, BH3, BH4, BH5, BH7, BH9,

BH11, BH12, BH13, BH14), and 3) creating

knowledge via board meetings, formal meetings, and

cross-functional teams (internal socialization) (BH3,

BH8, BH9, BH12, BH13, BH14). Moreover, while

external sensing and external socialization

capabilities were established by independent, chain

and multi-sector group-owned boutique hotels,

routines for internal socialization were only

established by independently owned and multi-sector

group-owned boutique hotels, with chain-owned

boutique hotels falling short of establishing

systemized processes to elicit ideas by way of internal

socialization activities.

Validation capabilities, which mirrored firm-level

processes deployed by boutique hotels to test ideas

and conduct research to determine the viability of

ideas, were only present in multi-sector group owned

boutique hotels (BH12, BH13, BH14), with these

hotels possessing the institutional structures required

to investigate and substantiate proposed ideas and test

innovations prior to their full rollout.

Knowledge creation capabilities, which were

established through formal and systemized meetings,

board meetings, and cross-functional teams, were

only established in three independently owned

boutique hotels (BH3, BH4, BH9), both chain-owned

boutique hotels (BH10, BH11), and all three multi-

sector group-owned boutique hotels (BH12, BH13,

BH14). Therefore, knowledge creation capabilities

were most prevalent in larger organizational

structures, where institutional routines for combining

knowledge resources and developing new

knowledge/ideas were established.

The seizing capability, which mirrors routines for

decision-making, emerged to reflect a complex

construct, with two decision-making paths available

to boutique hotel owners and managers/supervisors,

including 1) decision-making consensus and 2) the

immediate implementation of ideas. In the sample

investigated, decision-making consensus evolved to

represent a standardized procedure in all the boutique

hotels investigated in this research (BH1, BH2, BH3,

BH4, BH5, BH6, BH7, BH8, BH9, BH10, BH11,

BH12, BH13, BH14). Due to the unpredictable nature

of ‘immediate implementation’, this capability

evolved to mirror a cognitive capacity contingent on

boutique hotel owners/managers/supervisors to

deploy and implement.

Knowledge reconfiguration capabilities, which

reflect knowledge assembly processes, were only

systemized by multi-sector group-owned boutique

hotels (BH12, BH13, BH14), which comprised HR

departments with formalized responsibilities and

tasks for identifying knowledge gaps in the respective

hotels.

Knowledge integration capabilities, which mirror

institutionalized routines for sharing knowledge,

were systemized by boutique hotels through formal

in-person discussions (BH1, BH2, BH7, BH8, BH10,

BH11, BH13, BH14), discussions via instant

messaging platforms (BH2, BH4, BH5, BH6, BH9),

handover manuals (BH2, BH6), updated protocols

(BH6, BH8, BH9), emails (BH5, BH8, BH11), and

intranets (BH12, BH14).

The results of this study indicate that multi-sector

group-owned boutique hotels comprised the highest

levels of systemization for reconfiguring knowledge

resources and developing innovation, with these

hotels possessing all six capabilities. Chain-owned

and independently owned boutique hotels also

comprised firm-level capabilities for reconfiguring

knowledge resources, however, out of six capabilities,

these hotels only possessed four capabilities (sensing

capabilities, knowledge creation capabilities, seizing

capabilities, and knowledge integration capabilities),

with no independently owned boutique hotel

possessing all four capabilities. Through this analysis,

this study delineates that in independently owned

boutique hotels, innovation processes emerged as

informally structured and largely contingent on

micro-foundation processes for the reconfiguration of

knowledge resources, while multi-sector group-

Innovation in Boutique Hotels in Valletta, Malta: A Multi-level Investigation

101

owned boutique hotels possessed the highest degrees

of formalization in the innovation process. Thus, in

this research, the larger infrastructures of multi-sector

group-owned boutique hotels seemed to exert a

positive influence on ability of these organizations to

establish institutional routines for reconfiguring

knowledge resources and developing innovation.

When exploring the role and the impact of firm-

level capabilities for reconfiguring knowledge

resources and developing innovation in boutique

hotels, the results of this study outline that

respondents from chain-owned and multi-sector

group owned boutique hotels reported implementing

a larger number of novel innovations when contrasted

against the number of innovations reported by

independently owned boutique hotels during three

contextual periods, being: 1) prior to the opening of

boutique hotels, 2) operational phase of boutique

hotels, and 3) Covid-19 phase. According to the

results obtained, firm-level capabilities for

reconfiguring knowledge resources assisted chain-

owned and multi-sector group-owned boutique hotels

through: 1) providing systemized methods for

identifying innovation opportunities, 2) acting as an

avenue to overcome market turbulence through

adaptation efforts, and 3) acting as a method to

sustain innovation activities over longer temporal

dimensions. In this respect, while multi-sector group

owned boutique hotels possessed six firm-level

capabilities, four firm-level capabilities emerged to

play a pivotal role in the innovation efforts of both

chain-owned and group-owned boutique hotels,

including 1) sensing capabilities, 2) knowledge

creation capabilities, 3) seizing capabilities, and 4)

knowledge integration capabilities.

Therefore, in line with the results presented in this

section, in this research, firm-level knowledge

reconfiguration capabilities were most prevalent in

larger organizational structures, including chain-

owned and multi-sector group-owned boutique hotels.

Consistency in knowledge reconfiguration

capabilities, specifically, the routinization of the

sensing capability, knowledge creation capability,

seizing capability, and knowledge integration

capability, assisted the investigated boutique hotels to

systematically identify innovation opportunities,

reconfigure knowledge resources, and adapt to

market turbulence through implementing innovations.

While firm-level capabilities for reconfiguring

knowledge resources emerged as instrumental in

larger boutique hotels, the complex, subjective and

human-centric nature of idea generation processes

hindered the wide-scale development of systemized

sensing capabilities.

Therefore, the core stimulus required to ignite the

innovation process, being ideas, which manifest as

subjective tacit knowledge, resides within the

cognitive facilities of the personnel constituting

boutique hotels. Thus, in the investigated boutique

hotels, innovation emerged as contingent on both

micro-level and firm-level capabilities, with these

hotels inherently contingent on intra-organizational

personnel to effectuate idea generation efforts.

5 DISCUSSION

Based on the results obtained in this research, in the

investigated boutique hotels, innovation emerged to

reflect a complex knowledge-based process, with

transformations in knowledge resources acting as a

basis for: 1) the identification of innovation

opportunities, 2) the development of novel ideas, and

3) the subsequent exploitation of ideas to result in

innovation. This, in itself, aligns to prior

conceptualizations of service innovation (see, for

example, Galanakis, 2006; Peschl & Fundneider,

2014; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 2019), where authors

positioned service innovation to comprise a

knowledge-based process involving combinations of

knowledge resources from multiple intra- and inter-

organizational actors (Lusch & Nambisan, 2015;

Miles, 2008). Unlike prior conceptualization of

service innovation, however, where innovation

processes have been defined by a reductionist

approach (Song et al., 2009; Toivonen & Tuominen,

2009), at a micro-foundation level, innovation

emerged to be rooted in a nine-phase knowledge

reconfiguration process, with idea generation, the

core stimulus and input necessary to start the

innovation process, following the principles of

equifinality, i.e., boutique hotel employees and

owners bore the capacity to gestate novel thoughts

through four idiosyncratic paths. As a result, at a

micro-level of analysis, innovation efforts in boutique

hotels reflected a nuanced, personal, subjective, and

complex process, with hotels emerging as inherently

contingent on intra-organizational personnel to

identify innovation opportunities, generate novel

ideas, and externalized ideas via a co-created context.

When positioned in this light, the rate of innovation

in boutique hotels evolved as partially determined by

the motivations of hotel employees and owners to: 1)

engage in innovation opportunity identification

activities and 2) externalize/share their subjective

tacit knowledge with colleagues. This, in turn, is in-

line with Ardichvili et al.’s (2003) theoretical

standpoint of opportunity development, and Amabile

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

102

and Pratt’s (2016) perspective of innovation, where

the authors asserted that “at the individual level, the

driver is intrinsic motivation” (p. 160). In addition,

given the core role of social interactions and dialogue

in the service innovation processes comprising the

investigated boutique hotels, the overarching culture

and climate present within boutique hotels was found

to bear a degree of influence over the innovation

processes adopted in these organizations. This finding

is in line with Goodman and Dingli’s (2013) rationale

concerning the pivotal role of trust, emotional safety,

and openness in the innovation process. Similar to

previous findings (Crossan & Berdrow, 2003), the

innovation process in boutique hotels emerged as

particularly influenced by the decision-making power

and authority of owners, most significantly in

independently owned and chain-owned boutique

hotels, where decision-making consensus regarding

potential ideas was generally necessitated prior to

implementing innovations. Alternatively, in multi-

sector group-owned boutique hotels, managers

possessed the capacity to implement innovations at

their discretion, as long as such innovations fit within

pre-defined financial parameters which, in turn,

aligns to Gutierrez et al.’s (2008) findings. Unlike

previous studies, however, this study also found that

the number of innovation processes implemented by

boutique hotels was influenced by ownership

structures, with multi-sector group-owned boutique

hotels possessing the longest innovation cycle,

followed by independently owned boutique hotels.

Chain-owned boutique hotels possessed the shortest

innovation cycle, with these hotels neglecting to test

ideas, assemble knowledge resources, and acquire

feedback post-innovation. Thus, not only do

ownership structures exert an impact on the rate and

the number of innovations which are

approved/rejected in boutique hotels, however,

different ownership structures also influence the

innovation process in terms of the number of micro-

foundation processes implemented by boutique

hotels.

Extending current research in the tourism

literature, where empirical investigations have

predominantly explored the link between knowledge

resources and innovation from a single-level

perspective, i.e., organizations are either explored at

the individual-level or the firm-level, and based on

positivist methodologies (Nordli, 2018;

Pongsathornwiwat et al., 2019; Thomas & Wood,

2014), the results of this study outline that boutique

hotels, specifically multi-sector group-owned

boutique hotels, possessed six capabilities aimed at

reconfiguring knowledge resources. Moreover, while

capabilities aimed at transforming knowledge

resources have been established in the literature (see,

for example, Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Kogut &

Zander, 1992; Nielsen, 2006), these capabilities

largely remain conceptual and fall short of

interlinking firm-level capabilities to micro-level

processes. This study explicates that larger

organizational structures promote the development of

firm-level capabilities, which is in-line with Zahra et

al.’s (2006) research, where the authors linked

dynamic capability development to small-to-medium

sized enterprises, new ventures, and mature

organizations. Therefore, this contradicts Teece’s

(2007) assertion that dynamic capabilities are

generally only established by multinational

organizations. All the boutique hotels comprising this

sample, possessed the ‘capacity’ to establish

systemized routines for reconfiguring knowledge

resources, with smaller independently run boutique

hotels generally establishing one or two firm-level

capabilities aimed at reconfiguring knowledge

resources. Thus, dynamic capability development is

still possible is small organizations, however,

admittedly, it is less prevalent. What the dynamic

capabilities approach has fundamentally neglected to

address, and what seems to be taken for granted in the

strategic management literature is the stickiness and

complex nature of the ‘sensing capability’. According

to prior conceptualizations, the sensing capability

reflects the (systematic/routinized) ability to “spot,

interpret, and pursue opportunities” (Pavlou & El

Sawy, 2011, p. 243). As was previously outlined, in

the boutique hotels investigated in this research, the

ability to sense innovation opportunities emerged to

reflect a heterogeneous construct intertwined in

personal, subjective, and individual-oriented

processes, with boutique hotels only managing to

systemize 6 out of 15 stimuli used to identify

innovation opportunities. Therefore, counter to the

strategic management literature (Pavlou & El Sawy,

2011; Teece, 2007; Teece et al., 1997), in this study,

the sensing capability largely mirrored an individual-

level cognitive capability, implying that kickstarting

the innovation process in boutique hotels commands

the individual efforts of hotel personnel.

6 CONCLUSION

In boutique hotels, both micro- and firm-level

processes/capabilities for reconfiguring knowledge

resources are necessitated and important for the

development of ideas and innovation. This empirical

Innovation in Boutique Hotels in Valletta, Malta: A Multi-level Investigation

103

investigation comprises implications for both

practitioners and theory.

For boutique hotel practitioners, this study

illustrates the core dependence boutique hotels have

on personnel for the development of ideas. As a

result, practitioners may use the micro-foundation

model to understand the stimuli used by personnel to

generate ideas, and to react by establishing

appropriate intrinsic and extrinsic motivators capable

of encouraging employees to externalize their

thoughts/ideas.

Given the importance of knowledge resources in

the innovation process, practitioners may use the

micro-foundation model as a basis to develop and

implement systems for the management of

knowledge. This, in turn, may assist practitioners

establish firm-level capabilities for systemized and

structured forms of innovation.

From a theoretical perspective, this paper

contributes to the literature by explicating the dual

levels through which innovation occurs in boutique

hotels, with innovation emerging as contingent on

both micro-level processes and firm-level

capabilities. This, in turn, overcomes the shortfalls of

simplified service innovation process models through

a comprehensive and empirically grounded model of

the service innovation process.

While this paper comprises implications for

practitioners and contributes towards theory

development, it comprises certain limitations. First,

this research did not explore the role of front-line

employees in the innovation process, this may reduce

the representativeness of the proposed models.

Therefore, future studies should seek to explore and

account for the role of all employees in the innovation

processes of hotels though, for example, the

application of a case study.

Second, in this research, innovation processes

were only investigated in boutique hotels, which

merely mirrors one type of accommodation provision.

Future studies may seek to explore whether

innovation processes vary in other types of

accommodation, e.g., 4- and 5-star hotels.

Third, due to the qualitative underpinnings of this

research, innovation in boutique hotels was

investigated by way of a constructivist lens. For more

replicable and objective research, future studies may

seek explore innovation processes through the

application of a critical realist approach.

REFERENCES

Amabile, T. M., & Pratt, M. G. (2016). The dynamic

componential model of creativity and innovation in

organizations: Making progress, making meaning.

Research in organizational behavior, 36, 157-183.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.10.001

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of

entrepreneurial opportunity identification and

development. Journal of Business venturing, 18(1), 105-

123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(01)000 68-4

Binder, P., Mair, M., Stummer, K., & Kessler, A. (2016).

Organizational innovativeness and its results: a

qualitative analysis of SME hotels in Vienna. Journal

of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(3), 339-363.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013496277

Buckley, P., & Majumdar, R. (2018, 12 July). The services

powerhouse: increasingly vital to world economic

growth. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/

economy/issues-by-the-numbers/trade-in-services-

economy-growth.html

Buhagiar, K. (2021). Interorganizational learning in the

tourism industry: conceptualizing a multi-level

typology. The Learning Organization, 28(2), 208-221.

https://doi.org/10.1108/TLO-01-2020-0016

Buhagiar, K., Pace, L. A., & Dingli, S. M. (2021). Service

Innovation: A Knowledge-based Approach. In

Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference

on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and

Knowledge Management (IC3K 2021) (pp. 119-125).

DOI: 10.5220/0010652900003064

Camisón-Zornoza, C., Forés-Julián, B., Puig-Denia, A., &

Camisón-Haba, S. (2020). Effects of ownership

structure and corporate and family governance on

dynamic capabilities in family firms. International

Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16, 1393-

1426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00675-w

Carlborg, P., Kindström, D., & Kowalkowski, C. (2014).

The evolution of service innovation research: a critical

review and synthesis. The Service Industries Journal,

34(5), 373-398. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.20

13.780044

Chesbrough, H. (2017). The future of open innovation: The

future of open innovation is more extensive, more

collaborative, and more engaged with a wider variety of

participants. Research-Technology Management,

60(1), 35-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08956308.20

17.1255054

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive

capacity: A new perspective on learning and

innovation. (technology, organizations, and

innovation). Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1),

128-152. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553

Crossan, M. M., & Berdrow, I. (2003). Organizational

learning and strategic renewal. Strategic Management

Journal, 24(11), 1087-1105. https://doi.org/10.1002/

smj.342

Duverger, P. (2012). Using dissatisfied customers as a

source for innovative service ideas. Journal of

Hospitality & Tourism Research, 36(4), 537-563.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

104

https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348011413591

Edghiem, F., & Mouzughi, Y. (2018). Knowledge-

advanced innovative behaviour: A hospitality service

perspective. International Journal of Contemporary

Hospitality Management, 30(1), 197-216.

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2016-0200

Engen, M., & Magnusson, P. (2018). Casting for service

innovation: The roles of frontline employees. Creativity

and Innovation Management, 27(3), 255-269.

https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12263

Espejo, R., & Dominici, G. (2017). Cybernetics of value

cocreation for product development. Systems Research

and Behavioral Science, 34(1), 24-40.

https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2392

Galanakis, K. (2006). Innovation process. Make sense using

systems thinking. Technovation, 26(11), 1222-1232.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2005.07.0 02

Gallouj, F., & Savona, M. (2009). Innovation in services: a

review of the debate and a research agenda. Journal of

evolutionary economics, 19(2), 149-172.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-008-0126-4

Ghaderi, Z., Dehghan Pour Farashah, M. H., Aslani, E., &

Hemati, B. (2020). Managers’ perceptions of the

adaptive reuse of heritage buildings as boutique hotels:

Insights from Iran. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(6),

696-708. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2020.1756

834

Goodman, M., & Dingli, S. M. (2013). Creativity and

strategic innovation management: Directions for future

value in changing times (1st Ed). Routleg.

Grant, R. M. (1996a). Toward a knowledge-based theory of

the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(s2), 109-

122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171110

Gustafsson, A., Snyder, H., & Witell, L. (2020). Service

innovation: a new conceptualization and path forward.

Journal of Service Research, 23(2), 111-115.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520908929

Gutierrez, E., Sandstrom, G. O., Janhager, J., & Ritzen, S.

(2008, September). Innovation and decision making:

understanding selection and prioritization of

development projects. Paper presented at the 2008 4th

IEEE International Conference on Management of

Innovation and Technology, Bangkok, Thailand.

10.1109/ICMIT.2008.4654386

Hidalgo, A., & D'Alvano, L. (2014). Service innovation:

Inward and outward related activities and cooperation

mode. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 698-703.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.030

Keszey, T. (2018). Boundary spanners’ knowledge sharing

for innovation success in turbulent times. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 22(5), 1061-1081.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2017-0033

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm,

combinative capabilities, and the replication of

technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383-397.

https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.3.383

Li, M., & Hsu, C. H. (2016). Linking customer-employee

exchange and employee innovative behavior.

International Journal of Hospitality Management, 56,

87-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.04.015

Loureiro, S. M. C., Rita, P., & Sarmento, E. M. (2019).

What is the core essence of small city boutique hotels?.

International Journal of Culture, Tourism and

Hospitality Research, 14(1), 44-62.

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-01-2019-0007

Lusch, R. F., & Nambisan, S. (2015). Service innovation:

A service-dominant logic perspective. MIS quarterly,

39(1), 155-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/20

15/39.1.07

Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2018). An overview of

Service-Dominant Logic. In Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S.

L. (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Service-Dominant

Logic (pp. 3-21). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526470355.n1

Miles, I. (2008). Patterns of innovation in service industries.

IBM Systems journal, 47(1), 115-128. DOI:

10.1147/sj.471.0115

Nielsen, A. P. (2006). Understanding dynamic capabilities

through knowledge management. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 10(4), 59-71.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270610679363

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational

knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14-37.

https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating

company: How Japanese companies create the

dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford university

press.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (2019). The Wise Company:

How Companies Create Continuous Innovation. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Nordli, A. J. (2018). Information use and working methods

as drivers of innovation in tourism companies.

Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism,

18(2), 199-213. https://doi.org/10.1080/150222

50.2017.1343682

Parolin, C., & Boeing, R. (2019). Consumption of boutique

hotel experiences as revealed by electronic word-of-

mouth. Tourism & Management Studies, 15(2), 33-45.

Pavlou, P., & El Sawy, O. (2011). Understanding the

elusive black box of dynamic capabilities. Decision

Sciences, 42(1), 239-273. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1540-5915.2010.00287.x

Peschl, M. F., & Fundneider, T. (2014). Designing and

enabling spaces for collaborative knowledge creation

and innovation: From managing to enabling innovation

as socio-epistemological technology. Computers in

Human Behavior, 37, 346-359. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.chb.2012.05.027

Pongsathornwiwat, A., Jeenanunta, C., Huynh, V., &

Udomvitid, K. (2019). How collaborative routines

improve dynamic innovation capability and

performance in tourism industry? A path-dependent

learning model. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism

Research, 24(4), 281-295. https://doi.org/10.1080/

10941665.2018.1564341

Singh, S., Akbani, I., & Dhir, S. (2020). Service innovation

implementation: a systematic review and research

agenda. The Service Industries Journal, 40(7-8), 491-

517. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2020.1731477

Innovation in Boutique Hotels in Valletta, Malta: A Multi-level Investigation

105

Snyder, H., Witell, L., Gustafsson, A., Fombelle, P., &

Kristensson, P. (2016). Identifying categories of service

innovation: A review and synthesis of the literature.

Journal of Business Research, 69(7), 2401-2408.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.009

Song, L. Z., Song, M., & Di Benedetto, C. A. (2009). A

staged service innovation model. Decision Sciences,

40(3), 571-599. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-

5915.2009.00240.x

Sundbo, J. (1997). Management of innovation in services.

Service Industries Journal, 17(3), 432-455.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069700000028

Sundbo, J. (2009). Innovation in the experience economy:

a taxonomy of innovation organisations. The Service

Industries Journal, 29(4), 431-455.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060802283139

Statista Research Department. (2022, 8 September). Malta:

Share of economic sectors in gross domestic product

(GDP) from 2011 to 2021.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/731269/share-of-

economic-sectors-in-the-gdp-in-malta/

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the

nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise

performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13),

1319-1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic

capabilities and strategic management. Strategic

Management Journal, 18(7), 509-533.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-

0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

Thomas, R., & Wood, E. (2014). Innovation in tourism: Re-

conceptualising and measuring the absorptive capacity

of the hotel sector. Tourism Management, 45, 39-48.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.03.012

Tidd, J., & Bessant, J. (2014). Strategic Innovation

Management. United Kingdom: John Wiley &Sons

Ltd.

Toivonen, M., & Tuominen, T. (2009). Emergence of

innovations in services. The Service Industries Journal,

29(7), 887-902. https://doi.org/10.1080/0264206090

2749492

Varela, H, R., & Beer, S. S., (1980). Autopoiesis and

Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Holland: D.

Reidel Publishing Company.

Witell, L., Snyder, H., Gustafsson, A., Fombelle, P., &

Kristensson, P. (2016). Defining service innovation: A

review and synthesis. Journal of Business Research,

69(8), 2863-2872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.20

15.12.055

Xu, F. Z., & Wang, Y. (2020). Enhancing employee

innovation through customer engagement: The role of

customer interactivity, employee affect, and

motivations. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism

Research, 44(2), 351-376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096

348019893043

Zahra, S. A., Sapienza, H. J., & Davidsson, P. (2006).

Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review,

model and research agenda. Journal of Management

studies, 43(4), 917-955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-

6486.2006.00616.x

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

106