Emotional Interpretation of Opera Seria:

Impact of Specifics of Drama Structure

(Position Paper)

Pablo Gerv

´

as

1 a

and

´

Alvaro Torrente

2 b

1

Facultad de Inform

´

atica, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, 28040, Spain

2

Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, 28040, Spain

Keywords:

Sentiment Analysis, Italian Opera, Opera Seria, Emotion.

Abstract:

The application of artificial intelligence techniques to help musicologists analyse and classify operatic arias in

terms of the sentiment they might be expressing constitutes a novel task that may benefit from the application

of sentiment analysis techniques. However, because the analysis of text in this instance aims to provide

information to support the analisis of the associated music, the conventions of how narrative is structured in

traditional opera need to be taken into account to ensure that the relevant spans of text are considered. The

present position paper argues for a treatment of operatic libretti as semi-structured data, to take advantage

of annotations on speaker identity and recitative vs. aria distinctions so that the most relevant sentiment for

the music of the arias can be mined from the texts. This would constitute a new task that applies artificial

intelligence specifically to the needs of musicology.

1 INTRODUCTION

There is growing interest in exploring the applica-

tion of artificial intelligence techniques to help musi-

cologists analyse and classify operatic arias in terms

of the sentiment they might be expressing. This has

followed recent advances in the quality of sentiment

analysis solutions. For a musicologist, being able to

tell whether an aria might be expressing a particu-

lar sentiment opens the gate to identifying which of

the musical features of the piece might be serving the

purpose of expressing that sentiment (Torrente and

Dom

´

ınguez, 2022). However, in the particular con-

text of opera, particularly opera seria, direct appli-

cation of the procedures developed to attribute senti-

ment to news headlines or Twitter messages may not

be the optimal approach, given the specific relations

that hold between the sentiment expressed in an aria,

the text of the aria, and the text of the recitative that

has lead to the aria.

Opera seria is an Italian term used to describe

the operatic genre that prevailed among the courts of

Europe during most of the 18th century. It is char-

acterised by the alternation of recitative – where the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4906-9837

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5830-183X

performers engage in dialogue that carries the action,

sung in a style very close to normal speech and ac-

companied only by a limited subset of instruments

– and arias – where solo singers elaborate on the

feelings of a particular character and sing complex

melodies accompanied by the whole orchestra (Fab-

bri, 2003). This convention was very strictly followed

at the time.

1

The texts were always written in Italian,

no matter the nationality of the composer or the coun-

try were they were performed.

The present position paper argues that this singu-

lar structure of opera seria needs to be considered

when attempting automated treatment of the libretti to

annotate the emotional content being expressed in the

arias. The conventions of opera seria allow very com-

plex dramatic situations to be set up during the longer

recitatives, so that they can be given musical expres-

sion in the arias. But the arias themselves usually

have very short texts, that very often express abstract

or metaphoric references to the situation in question,

rather than descriptions of them, because they rely for

that on the material just presented in the preceding

recitative. This presents a challenge to the artificial in-

telligence researcher attempting to run his sentiment

1

A brief review of evidence in support of this statement

is provided in section 2.1 below.

330

Gervás, P. and Torrente, Á.

Emotional Interpretation of Opera Seria: Impact of Specifics of Drama Structure (Position Paper).

DOI: 10.5220/0011588900003335

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2022) - Volume 1: KDIR, pages 330-336

ISBN: 978-989-758-614-9; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

analysis code on the text of the aria to obtain a mean-

ingful representation of the feelings being expressed

by the music of the aria. In the sections that follow we

present a more elaborate argument in support of this

point of view, and a simple computational experiment

to show the significant differences in relative size be-

tween the volume of text of the arias and the volume

of text of the recitatives that precede them.

2 PREVIOUS WORK

The following topics are reviewed: basic conventions

of opera seria and existing work on identifying emo-

tion in Italian opera.

2.1 Basics of Operatic Convention on

Narrative

The chief structural principle of opera seria is the al-

ternation of recitatives, where the plot action is ex-

pressed with simple music and accompaniment, and

arias, where the characters express their feelings in

elaborate musical settings with orchestra. This divi-

sion, that may look artificial to a modern audience,

appears to be a direct reflection of Ren

´

e Descartes’

theory of human emotions as described in Les pas-

sions de l’

ˆ

ame (Descartes, 1649) doubtless the most

influential essay on this matter for more than a cen-

tury. Descartes uses the term passion to imply that

human emotions are the reaction of the mind and the

body to a certain action. As a consequence of this

conception, the mechanics of opera seria consist of a

sequence of actions during the recitatives that succes-

sively arouse specific passions in one or more char-

acters that are in turn being expressed in their arias

(Torrente and Llorens, 2020). For more than a cen-

tury, arias followed the same structural pattern be-

cause ’form must be comprehensible if a work is to

achieve its goal of moving the audience’s passions’

(Bonds, 1991, p. 81). The key to this separation is

that the emotional conflicts expressed musically on-

stage in the form of arias are the “true” musical drama

(Dahlhaus, 2003, p. 73). Usually, as the characters

might be experiencing a set of complex emotions, a

particular aria would attempt to represent a specific

aspect of those feelings (Hill, 2005, p. 390). Operas

were in fact a formal representation of an emotional

universe (Bianconi, 2008, p. 85).

2.2 Mining Emotions in Opera

The recent work of Shibingfeng (Shibingfeng, 2021;

Fernicola et al., 2020) addresses the automatic iden-

tification of emotion in Italian opera. This approach

is based on the assumption that an aria may transmit

more than one emotion, and to address this problem,

the task is defined in terms of identifying the emotions

transmitted by each specific stanza of the aria poem:

in opera seria most poems consist of just two stanzas.

To achieve this, a corpus of 2,500 aria stanzas was

annotated by two human annotators with the emo-

tions they attribute to it. A number of state-of-the-

art text representations and classification approaches

are tested over the corpus. Best performance was ob-

tained by using a character trigram based TF-IDF rep-

resentation and a neural network with 2 hidden layers

as classifier. This yielded an accuracy of 0.47 on the

test set. An extension of the work to assign emotions

at the aria level, using a convolutional neural network

combined with character trigram based embeddings

developed based on a corpus of Italian arias achieved

an accuracy of 0.68.

The annotated corpus of arias, the

AriEmozione1.0 corpus, has been made public

(Garcea et al., 2020).

3 RELATIVE DIFFERENCES IN

EMOTIONAL

INTERPRETATION CONTEXTS

FOR ARIAS

The general idea is that, given that the libretto is an

alternating sequence of spans of recitative followed

by an aria, it would be useful to consider that the aria

is intended to express the emotions felt by a particular

character (the singer) as a result of the accumulated

actions described in the preceding (span of) recitative.

This approach is made possible by the fact that

libretti for opera seria are not single stretches of se-

quential text, but rather a sequence of small spans of

text organised in a fixed structure of acts, scenes and

contributions of individual singers at given points in

time (Mu

˜

noz-Lago et al., 2020). The text of each of

these small spans is itself broken down into lines of

verse, though this feature does not influence the ar-

gument being put forward. The contributions by the

singers are also annotated to show whether they are

instances of recitative or of arias.

3.1 A Corpus of Machine-readable

Operas

For the purpose of this paper, we are work-

ing with XML representations of all the libretti

written by Pietro Metastasio, the principal li-

Emotional Interpretation of Opera Seria: Impact of Specifics of Drama Structure (Position Paper)

331

Table 1: A fragment of the libretto for the opera Didone

abandonata as represented in XML. The fragment includes

the first aria of the opera and some lines of the preceding

recitative.

(...)

<speaker>DIDONE</speaker>

<l left-margin="12" n="80" type="r">

Che?</l>

<speaker>ENEA</speaker>

<l left-margin="24" n="80" type="r">

La patria, il cielo...</l>

<speaker>DIDONE</speaker>

<br/>

<l n="81" type="a">&nbsp;&nbsp;

Parla.</l>

<br/>

<speaker>ENEA</speaker>

<br/>

<l left-margin="16" n="81" type="a">

Dovrei... Ma no...</l>

<l n="82" type="a">

L’amor... oh dio, la f

´

e...</l>

<l n="83" type="a">

Ah che parlar non so.</l>

<sp n="84" type="a">

<l n="84" type="a">

Spiegalo tu per me. </l>

<stage n="84">(Ad Osmida e parte)</stage>

</sp>

(...)

brettist in the eighteenth century,

2

that includes

specific labels to identify the singers in each

case (<speaker>ENEA</speaker>) and the specific

lines (<l n="82" type="a">), indicating for each

whether it corresponds to recitative (type="r") or

aria (type="a"). An example of a fragment of libretto

is shown in Table 1.

3.2 Examples of Recitative-aria

Pairings

The aria described in the previous section (Table 1)

also serves as an example of the situation described

to this point, where an aria of just 4 lines (81 to 84)

follows the preceding 80 lines of recitative.

In this example, the text of the aria basically trans-

lates into “I should ... But no ... Love ... oh god, the

faith ... Ah, what to talk about I don’t know. You

explain it for me.”

This text hardly allows the reader to make out

what the singer is feeling. Without the preceding 80

lines of recitative – which set out the situation at the

start of the opera, with Enea arguing with Didone that,

2

Kindly provided by Anna Laura Bellina , director

of the Progetto Metastasio at the University of Padova

http://www.progettometastasio.it/.

Table 2: Example of an aria preceded by a recitative (Di-

done abandonata, Act I, Scene III). The original XML has

been rendered as structured text for readability.

SCENA: SCENA III

[RECITATIVE]

(STAGE-DIRECTION): DIDONE, SELENE e OSMIDA

DIDONE:

85 Parte cos

`

ı, cos

`

ı mi lascia Enea?

86 Che vuol dir quel silenzio? In che son rea?

SELENE:

87 Ei pensa abbandonarti.

88 Contrastano quel core,

89 n

´

e so chi vincer

`

a, gloria ed amore.

DIDONE:

90

`

E gloria abandonarmi?

OSMIDA:

91 (Si deluda). Regina,

92 il cor d’Enea non penetr

`

o Selene.

93 Ei disse,

`

e ver, che il suo dover lo sprona

94 a lasciar queste sponde

95 ma col dover la gelosia nasconde.

DIDONE:

96 Come!

OSMIDA:

96 Fra pochi istanti

97 dalla regia de’ Mori

98 qui giunger dee l’ambasciador Arbace...

DIDONE:

99 Che perci

`

o?

OSMIDA:

99 Le tue nozze

100 chieder

`

a il re superbo e teme Enea

101 che tu ceda a la forza e a lui ti doni.

102 Perci

`

o cos

`

ı partendo

103 fugge il dolor di rimirarti.

DIDONE:

103 Intendo.

104 S’inganna Enea ma piace

105 l’inganno all’alma mia.

106 So che nel nostro core

107 sempre la gelosia figlia

`

e d’amore.

SELENE:

108 Anch’io lo so.

DIDONE:

108 Ma non lo sai per pruova.

OSMIDA:

109 (Cos

`

ı contro un rival l’altro mi giova).

DIDONE:

110 Vanne amata germana,

111 dal cor d’Enea sgombra i sospetti e digli

112 che a lui non mi torr

`

a se non la morte.

SELENE:

113 (A questo ancor tu mi condanni, o sorte!)

[ARIA]

SELENE:

114 Dir

`

o che fida sei,

115 su la mia f

´

e riposa.

116 Sar

`

o per te pietosa,

117 (per me crudel sar

`

o).

118 Sapranno i labri miei

119 scoprirgli il tuo desio.

120 (Ma la mia pena, oh dio,

121 come nasconder

`

o?)

(INDIVIDUAL-STAGE-DIRECTION):

(Parte)

in spite of this love for her, his destiny requires him

to leave his confortable life with her and her love,

and Didone objecting vehemently and arguing for the

merit of a life of love beside her – it is quite impossi-

ble to understand how Enea is feeling at this point.

To further illustrate the argument, Table 2 shows

a different fragment of the same opera, in which an

aria is preceded by a short recitative. In this case,

the text of the aria is slightly more expressive of the

feelings of the singer at that point (Didone will not

let someone else decide over her heart and fate), but

the preceding recitative outlines the actions that have

KDIR 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

332

triggered this response (her sister Selene has just told

her that Enea leaves because he fears the hurt of see-

ing her accept the marriage proposal she has just re-

ceived).

Table 3 shows a more complex and more con-

vincing example of the case in question, taken from

Metastasio’s Artaserse. The scene involves the trial

of Arbace, who is being falsely accused of murdering

the Persian King Serse. The assigned judge is Arta-

bano, Arbace’s father, who is the one who actually

killed Serse. Arbace knows that the real murderer is

his father, but during the trial filial piety stops him not

only from accusing his father, but also from defending

himself, to the surprise of all. Artabano sentences his

son to death for a murder that he himself has commit-

ted. At the end of the trial, Arbace pardons his father,

kisses his hand, and sings the aria “Per quel paterno

amplesso”. The text of this aria speaks about his fa-

ther’s embrace and his own loyalty to the crown. The

positive and even cheerful character of the poem does

not reflect Arbace’s inner feelings, having accepted

his own sacrifice for a crime committed by his father.

This cannot be grasped without taking into account

the preceding recitative.

3.3 Reading Libretti onto Meaningful

Data Structures

Fortunately the XML encoding allows very easily to

recover the recitatives that precede a given aria. The

main proposal of this position paper is that any emo-

tional analysis of the content of an aria from the point

of view of the text of the libretto – given that a ma-

jor point of interest of such an analysis for musicol-

ogy would be to identify which emotions might be

represented in the corresponding musical fragment –

should consider not just the text of the aria itself but

also the text of the recitative that separates that aria

from the preceding one.

The code for parsing the XML file of a libretto

builds a representation in Java. The resulting Java

classes are designed to capture the structure of nested

conceptual elements that constitutes the libretto. The

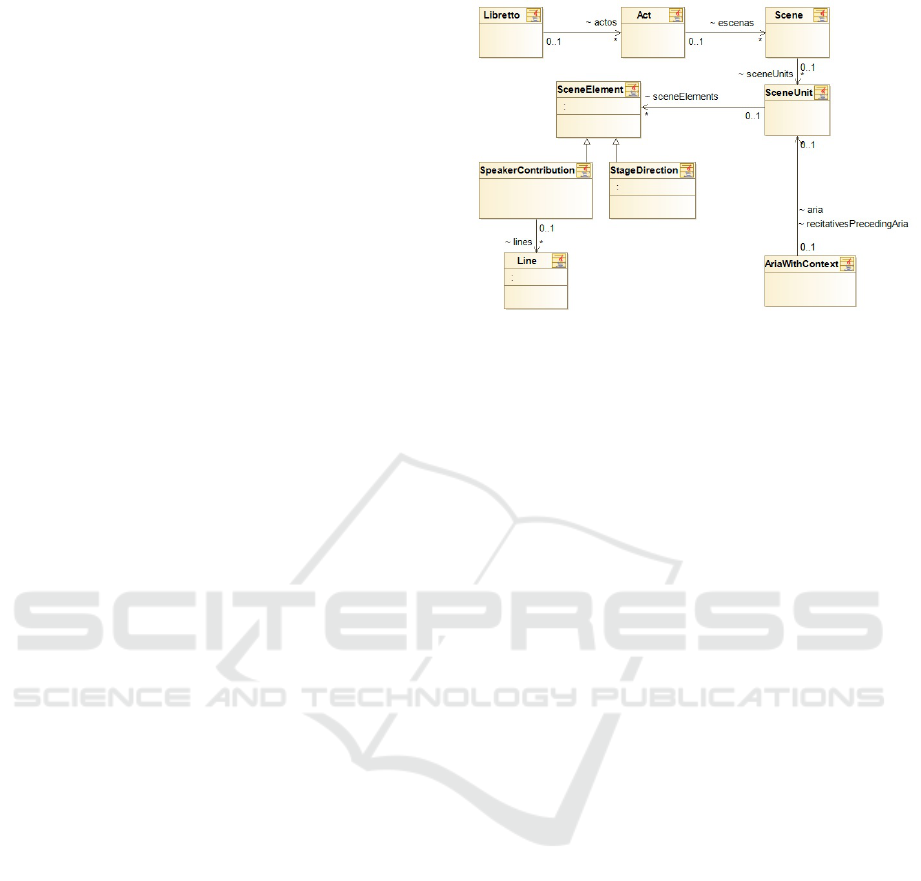

class diagram for this structure is shown in Figure 1

and explained below:

• Libretto class to represent a libretto for a full

opera, made up of instances of Atto (this repre-

sents the complete opera)

• Act class to represent an act, made up of instances

of Scene (these classes represent each of the acts

in the opera)

• Scene class to represent a scene, made up of in-

stances of SceneUnit (each act is broken down

Figure 1: Class Diagram Representing the Nested Structure

of Text Element in a Libretto.

into scenes, which are spans of the opera which

usually involve the same subset of the cast)

• SceneUnit class to represent a fragment of a

scene, that corresponds to either a recitative or

an aria; made up of instances of SceneElement

(with a scene, parts of it may be recitative and

parts of it may be arias)

• SceneElement mother class for elements in a

scene: speaker contributions or stage directions

• StageDirection extends SceneElement class to

represent a stage direction (the libretto includes

stage directions that are not spoken or sung but

which are placed within the corresponding scene)

• SpeakerContribution extends SceneElement

class to represent a contribution to a scene by a

given speaker, made up of separate lines repre-

sented as instances of Line (recitatives in partic-

ular, but sometimes also ensemble arias – duets,

trios –, are usually a sequence of alternating con-

tributions by different speakers; this class repre-

sents a set of lines contributed to the scene by

a given speaker without interruptions from other

speakers)

• Line class to represent a line of verse (represented

as a String) which may have an associated stage

direction (also represented as a String)

• AriaWithContext class to represent the associ-

ation between a SceneUnit class that represents

the aria is associated with a List<SceneUnit>

that represents the recitatives that precede it in the

sequence of the opera

A given libretto can now be parsed into a seqeunce

of instances of AriaWithContext class data struc-

tures, which allows easy retrieval of specific instances

of an aria together with the recitatives that precede it.

Emotional Interpretation of Opera Seria: Impact of Specifics of Drama Structure (Position Paper)

333

Table 3: Example of an aria preceded by a recitative (Artaserse, Act II, Scene XI). The original XML has been rendered as

structured text for readability. Some lines of the recitative not relevant to the point being made have been ommitted to match

space constraints.

SCENA: SCENA XI

[RECITATIVE]

(STAGE-DIRECTION): ARBACE, con catene fra alcune

guardie, e detti

ARBACE:

980 Tanto in odio alla Persia

981 dunque son io che di mia rea fortuna

982 l’ingiustizie a mirar tutta s’aduna!

983 Mio re.

ARTASERSE:

983 Chiamami amico. Infin ch’io possa

984 dubitar del tuo fallo, esser lo voglio.

985 E perch

´

e s

`

ı bel nome

986 in un giudice

`

e colpa, ad Artabano

987 il giudizio

`

e commesso.

ARBACE:

987 Al padre!

ARTASERSE:

987 A lui.

ARBACE:

988 (Gelo d’orror).

ARTABANO:

988 Che pensi? Ammiri forse

989 la mia costanza?

ARBACE:

989 Inorridisco, o padre,

990 nel mirarti in quel luogo. E ripensando

991 quale io son, qual tu sei, come potesti

992 farti giudice mio? Come conservi

993 cos

`

ı intrepido il volto? E non ti senti

994 l’anima lacerar?

ARTABANO:

994 Quei moti interni,

995 ch’io provo in me, tu ricercar non devi

996 n

´

e quale intelligenza

997 abbia col volto il cor. Qualunque io sia

998 lo son per colpa tua. Se a’ miei consigli

999 tu davi orecchio e seguitar sapevi

1000 l’orme d’un padre amante, in faccia a questi

1001 giudice non sarei, reo non saresti.

ARTASERSE:

1002 Misero genitor!

(...)

ARBACE:

1005 (Quanto rigor!)

ARTABANO:

1005 Dunque alle mie richieste

1006 risponda il reo. Tu comparisci, Arbace,

1007 di Serse l’uccisor. Ne sei convinto;

1008 ecco le prove. Un temerario amore,

1009 uno sdegno ribelle...

ARBACE:

1009 Il ferro, il sangue,

1010 il tempo, il luogo, il mio timor, la fuga

1011 so che la colpa mia fanno evidente.

1012 E pur vera non

`

e, sono innocente.

ARTABANO:

1013 Dimostralo se puoi; placa lo sdegno

1014 dell’offesa Mandane.

ARBACE:

1014 Ah se mi vuoi

1015 costante nel soffrir, non assalirmi

1016 in s

`

ı tenera parte. Al nome amato

1017 barbaro genitor...

ARTABANO:

1017 Taci, e non vedi

1018 nella tua cieca intoleranza e stolta

1019 dove sei, con chi parli e chi t’ascolta?

ARBACE:

1020 Ma padre...

ARTABANO:

1020 (Affetti, ah tolerate il freno!)

(...)

ARTABANO:

1034 Principessa,

`

e il tuo sdegno

1035 sprone alla mia virt

`

u. Resti alla Persia

1036 nel rigor d’Artabano un grand’essempio

1037 di giustizia e di f

´

e non visto ancora.

1038 Io condanno il mio figlio. Arbace mora.

(INDIVIDUAL-STAGE-DIRECTION):

(Sottoscrive il foglio)

(...)

ARTASERSE:

1039 Sospendi amico

1040 il decreto fatal.

ARTABANO:

1040 Segnato

`

e il foglio,

1041 ho compito il dover.

(INDIVIDUAL-STAGE-DIRECTION):

(S’alza e d

`

a il foglio ad Artaserse)

ARTASERSE:

1041 Barbaro vanto!

(INDIVIDUAL-STAGE-DIRECTION):

(Scende dal trono e i grandi si levano da sedere)

SEMIRA:

1042 Padre inumano!

(...)

ARTABANO:

1046 Di giudice severo

1047 adempite ho le parti. Ah si permetta

1048 agli affetti di padre

1049 uno sfogo o signor. Figlio perdona

1050 alla barbara legge

1051 d’un tiranno dover. Soffri, che poco

1052 ti rimane a soffrir. Non ti spaventi

1053 l’aspetto della pena; il mal peggiore

1054

`

e de’ mali il timor.

ARBACE:

1054 Vacilla o padre

1055 la sofferenza mia. Trovarmi esposto

1056 in faccia al mondo intero

1057 in sembianza di reo, veder recise

1058 sul verdeggiar le mie speranze, estinti

1059 su l’aurora i miei d

`

ı, vedermi in odio

1060 alla Persia, all’amico, a lei che adoro,

1061 saper che il padre mio...

1062 Barbaro padre... (Ah, ch’io mi perdo!) Addio.

(INDIVIDUAL-STAGE-DIRECTION):

(In atto di partire, poi si ferma)

ARTABANO:

1063 (Io gelo).

(...)

ARBACE:

1063 O temerario Arbace,

1064 dove trascorri? Ah genitor, perdono.

1065 Eccomi a’ piedi tuoi. Scusa i trasporti

1066 d’un insano dolor. Tutto il mio sangue

1067 si versi pur, non me ne lagno; e invece

1068 di chiamarla tiranna,

1069 io bacio quella man che mi condanna.

ARTABANO:

1070 Basta, sorgi, purtropo

1071 hai ragion di lagnarti;

1072 ma sappi... (Oh dei!) Prendi un abbraccio e parti.

ARBACE:

[ARIA]

ARBACE:

1073 Per quel paterno amplesso,

1074 per questo estremo addio,

1075 conservami te stesso,

1076 placami l’idol mio,

1077 difendimi il mio re.

1078 Vado a morir beato,

1079 se della Persia il fato

1080 tutto si sfoga in me.

(INDIVIDUAL-STAGE-DIRECTION):

(Parte fra le guardie seguito da Megabise e partono i grandi)

KDIR 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

334

Table 4: Proportion of of poetic lines for arias to recitatives

in Metastasio’s libretti.

Title % Arias % Recitative

Didone abbandonata 16.15 83.85

Siroe 16.38 83.62

Catone in Utica 15.74 84.26

Ezio 12.78 87.22

Semiramide 18.49 81.51

Alessandro nell’Indie 16.64 83.36

Artaserse 16.48 83.52

Demetrio 16.54 83.46

Issipile 16.68 83.32

Adriano in Siria 16.69 83.31

Olimpiade 16.39 83.61

Demofoonte 15.21 84.79

La clemenza di Tito 15.98 84.02

Achille in Sciro 21.11 78.89

Ciro riconosciuto 13.99 86.01

Temistocle 14.97 85.03

Zenobia 13.75 86.25

Ipermestra 17.35 82.65

Antigono 18.34 81.66

Attilio Regolo 16.02 83.98

Il re pastore 16.49 83.51

L’eroe cinese 15.56 84.44

Nitteti 16.73 83.27

Il trionfo di Clelia 14.57 85.43

Romolo ed Ersilia 19.10 80.90

Ruggiero 12.47 87.53

Over such data structures, the text of the associ-

ated recitatives can now be easily processed to iden-

tify any emotional connotations that might be relevant

for the emotional labelling of the aria.

3.4 Quantitative Data from the Corpus

Metastasio has 26 librettos with a total of 681 arias,

including alternative arias that he wrote for some li-

brettos and also the choirs; all that the Italians call

forme chiuse, different from the sciolti verses of the

recitative. The proportion of verses is 16% arias and

84% recitatives, although the range of arias oscillates

between 12.5% and 21.1% for arias. The relative per-

centages of aria and recitatives with respect to the full

length of the text is shown for the various libretti by

Metastasio in Table 4.

To illustrate the point from a quantitative point of

view, Table 5 shows the difference in volume of text

– measured in terms of number of lines – between

each of the arias and the recitative that precedes it for

Metastasio’s Artaserse. This table shows the signifi-

cant differences between arias in the same text, with

some cases where there is a very significant amount

of recitative to be analysed to inform the emotions ex-

pressed in the aria that follows.

Table 5: Relative differences between the average sizes of

each aria and the preceding span of recitative – expressed

in number of lines – for Metastasio’s Didone abandonata –

left hand column – and Artaserse – right hand column.

Recitative Aria

178 5

33 8

96 6

31 7

29 8

7 6

71 8

25 8

33 7

3 6

134 8

66 12

18 10

16 9

44 10

37 8

3 8

95 8

29 8

9 7

51 6

33 9

5 8

169 8

8 9

55 7

6 8

101 6

22 8

6 8

0 3

115 8

73 8

48 4

48.5 7.6

Recitative Aria

103 7

36 8

66 6

38 8

56 8

11 12

196 7

13 8

3 6

49 12

12 10

52 10

83 12

84 8

48 8

50 9

8 9

222 8

30 8

24 12

18 6

6 9

0 4

61 10

5 7

67 8

6 8

37 10

6 6

198 16

163 6

56.5 8.6

4 DISCUSSION

The emotion that the aria is expressing is not the re-

sult of its text exclusively, but rather of the narrative

developments in the preceding recitative. The text of

the aria is possibly intended as linguistic elaboration

on the emotions in question, but the music is surely

intended to represent the emotion felt by the charac-

ter at that point in the drama, which is not necessarily

clearly captured by the text of the aria. If it were, the

whole point of opera as a genre would be put in ques-

tion, as the dramatic recitatives leading to the aria, in-

cluding all the dialogues between the characters and

the development of the plot, would be dispensable.

Emotional Interpretation of Opera Seria: Impact of Specifics of Drama Structure (Position Paper)

335

The nature of opera libretti as documents sub-

ject to conventions on the need to indicate the overall

structure of the drama – as a sequence of acts built

of scenes – the specifics of verse sung by each per-

former – lines corresponding to a particular speaker

– and even the type of contribution – either recita-

tive or aria – allows this to be achieved with relative

ease. The libretto of a particular opera can then be

seen as semi-structured data, with these overarching

annotations providing a complex structure that deliv-

ers spans of text at particular points, while providing

with very specific details on their role in the context

of the opera.

5 CONCLUSIONS

There is a fundamental difference between sentiment

analysis of text as applied in other disciplines – such

as news headlines or Twitter messages – and its po-

tential application in musicology. Whereas for the

analysis of news or items in a Twitter feed the text

itself is the main and the only source of information,

for the study of opera the text comes accompanied by

an elaborate musical work which contributes at least

as much as the text – and very possibly much more

– to the emotions being expressed. When musicolo-

gists consider the emotions expressed in the text ele-

ments of an opera, it is not so much to obtain a single

value that is the only source of information, but rather

in search of additional information that may support

their analyses of the emotion that the corresponding

music is expressing.

The present paper argues that, in this endeavour,

the text of the recitatives preceding an aria should

be taken into consideration with special importance

when trying to identify the emotions that (the music

for) an aria should be considered to be trying to ex-

press.

This argument in no way intends to question the

merit of application of sentiment analysis to the text

of the arias themselves. Rather it proposes a slightly

different task, possibly resorting to the same tools and

techniques, but considering a slightly wider scope of

text in their application to ensure that the best sources

for emotional information are employed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper has been partially funded by the projects

CANTOR: Automated Composition of Personal Nar-

ratives as an aid for Occupational Therapy based on

Reminescence, Grant. No. PID2019-108927RB-I00

(Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation) and the

Didone Project (http://didone.eu) funded by the

European Research Council (ERC) under the Euro-

pean Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation

programme, Grant agreement No. 788986.

REFERENCES

Bianconi, L. (2008). La forma musicale come scuola dei

sentimenti. In Bianconi, G. L. F. and Frabboni, F.,

editors, Educazione musicale e formazione, pages 85–

120. FrancoAngeli, Milan.

Bonds, M. E. (1991). Wordless Rhetoric: Musical Form

and the Metaphor of the Oration. Harvard University

Press.

Dahlhaus, C. (2003). The Dramaturgy of Italian Opera. In

Bianconi, L. and Pestelli, G., editors, Opera in The-

ory and Practice, Image and Myth, volume 6 of The

History of Italian Opera, pages 73–150. University of

Chicago Press, Chicago.

Descartes, R. (1649). Les passions de l’

ˆ

ame. Henry Le

Gras, Paris.

Fabbri, P. (2003). Metrical and formal organization. In

Bianconi, L. and Pestelli, G., editors, Opera in The-

ory and Practice, Image and Myth, volume 6 of The

History of Italian Opera, pages 151–219. University

of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Fernicola, F., Zhang, S., Garcea, F., Bonora, P., and Barr

´

on-

Cede

˜

no, A. (2020). Ariemozione: Identifying emo-

tions in opera verses. In Monti, J., Dell’Orletta, F., and

Tamburini, F., editors, Proceedings of the Seventh Ital-

ian Conference on Computational Linguistics, CLiC-

it 2020, Bologna, Italy, March 1-3, 2021, volume 2769

of CEUR Workshop Proceedings. CEUR-WS.org.

Garcea, F., Bonora, P., Pompilio, A., Barr

´

on-Cede

˜

no, A.,

Fernicola, F., and Zhang, S. (2020). Ariemozione 1.0.

Hill, J. W. (2005). Baroque Music: Music in Western Eu-

rope 1580-1750. Norton, New York,.

Mu

˜

noz-Lago, P., Usula, N., Parada-Cabaleiro, E., and Tor-

rente, A. (2020). Visualising the structure of 18th

century operas: A multidisciplinary data science ap-

proach. In 24th International Conference Information

Visualisation, pages 508–514.

Shibingfeng, Z. (2020/2021). Emotion Identification in Ital-

ian Opera. Tesi di laurea, Universit‘a di Bologna.

Torrente, A. and Dom

´

ınguez, J. M. (2022). The Language

of Emotions from Descartes to Metastasio. In Arolas,

I. P., editor, Cognate Music Theories: The Past and

the Other in Musicology. Routledge, London.

Torrente, A. and Llorens, A. (2020). ”Misero pargoletto”:

Kinship, taboo and passion in Metastasio’s Demo-

foonte. In Jon

´

a

ˇ

sov

´

a, M. and Volek, T., editors, De-

mofoonte come soggetto per il dramma per musica,

pages 57–86. Academia, Prague.

KDIR 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

336