Social Determinant of Health for Smoke-Free Homes to Protecting

Children Become Smoker (Passive or Active)

Nur Rohmah

Department of Health Promotion, Faculty of Public Health, Mulawarman University, Samarinda, Indonesia

Keywords: Social Determinant, Smoke-Free Homes.

Abstract: This article is a literature review to design how smoking behavior prevention programs in children who will

become passive smokers or active smokers in the future with a compressive approach from the individual

level, organizational level, and community level. The social, physical, and economic situations in which

people are born, live, work, and age are social determinants of health. Infectious and non-communicable

diseases are affected by social determinants. This article aims to explain why we need to establish a smoke-

free home, as seen from the social determinants of health for smoking, to protect children from becoming

active or passive smokers. The meaning of social determinants and health inequity, based on own knowledge

of smoke-free homes, determines social determinants of health not only from social and health factors but

also from other factors including biology, psychology, economy, and politics. Therefore, social determinants

of health can be determined comprehensively from the environment in which people are born, live, work, and

age.

1

INTRODUCTION

Social determinant of health: a condition in the social,

physical, and economic environment in which people

are born, live, work, and age. Social determinants are

relevant to communicable and non-communicable

diseases. As smoking is an acknowledged risk factor

for a range of chronic diseases, developing

approaches to reduce tobacco use is critical.

Identification of factors associated both with smoking

initiation and cessation may help to underpin

strategies for smoke-free homes.

Various efforts have been made to reduce

smoking behavior, such as the failure to implement

indoor smoking bans (Abramova, Sami, & Huh,

2017), media campaigns (Been et al., 2014), smoking

restriction legislation, and tobacco taxation is among

policies implemented to reduce cigarette smoking

rates. Various factors include the influence of media,

parents, family, friends, and stress (Rohmah, 2013;

Rohman & Psi, 2010; WHO, 2010). Cigarette

initiation is associated with parental smoking and low

levels of maternal education (Conwell et al., 2003).

Why do we care about passive smokers? Because

there is still high smoking at home, the impacts of

cigarette smoke are not only for smokers but also

those around them as passive smokers. The First

effect to physic as second-hand smoke such as lung

cancer (Eng et al., 2014), leukemia (Lee et al., 2009),

malnutrition (Best et al., 2008), asthma, and ear

infection (Hawkins & Berkman, 2011; Wakefield et

al., 2000), increased risk of infant and under-5 child

mortality (Semba et al., 2008), low birth weight (Been

et al., 2014) and allergic (Thacher et al., 2014). The

second effect is psychological, such as depression or

stress (WHO, 2010). The third effect, social norms,

was more important than perceived parental

involvement in explaining cigarette consumption

(Olds & Thombs, 2001). Fathers' warmth and

hostility were the best predictors of heavy smoking

by sons (White, Johnson, & Buyske, 2000). Social

pressure from peers or older siblings has been

considered a prime factor for initial experimentation

(Leventhal & Cleary, 1980).

The meaning of the social determinants and health

inequity is based on knowledge of smoke-free homes

and the determination of social determinants of health

not only from social and health factors but also from

other factors like biology, psychology, economy, and

politics. There comprehensively social determinants

of health can be determined from the environment in

which people are born, live, work, and age.

Rohmah, N.

Social Determinant of Health for Smoke-Free Homes to Protecting Children Become Smoker (Passive or Active).

DOI: 10.5220/0011642400003608

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Social Determinants of Health (ICSDH 2022), pages 147-153

ISBN: 978-989-758-621-7; ISSN: 2975-8297

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

147

This article aims to explain why we need to

establish a home free from cigarette smoke as seen

from the social determinants of health for smoking, to

protect children from active or passive smokers.

2 LITERATURE STUDY

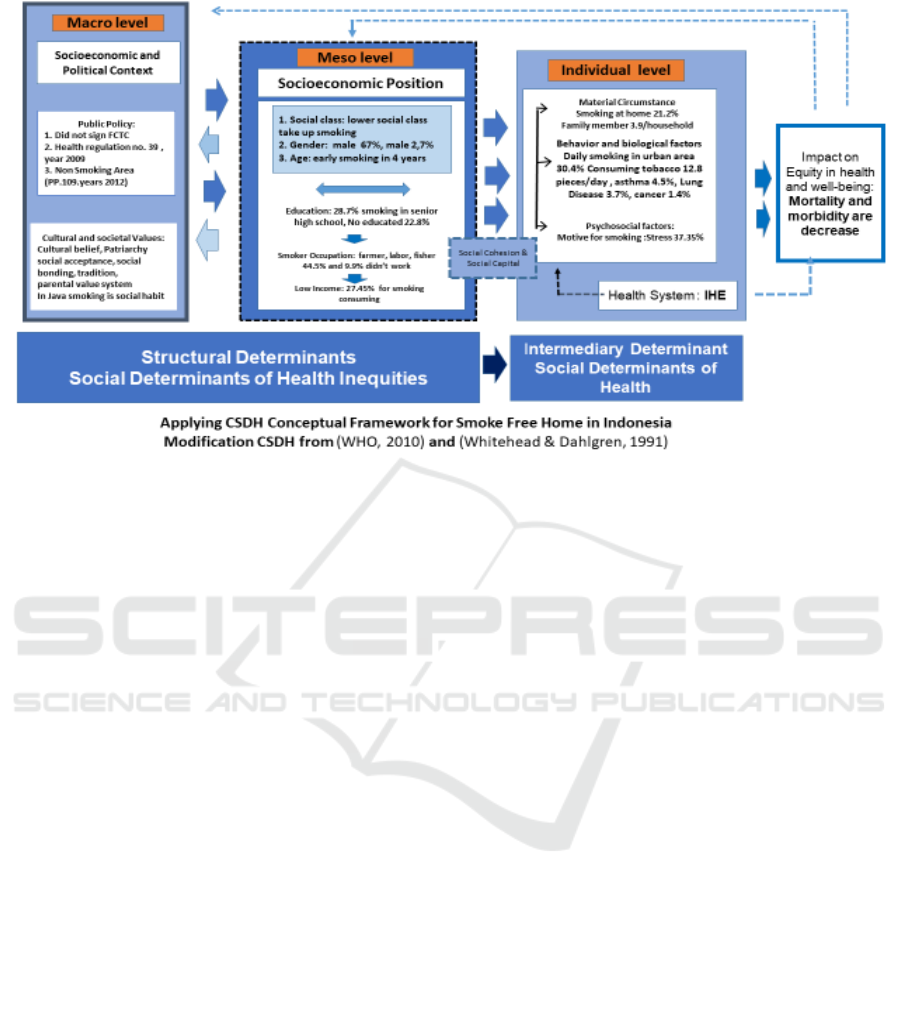

2.1 Theories Conceptual Framework

Social Determinants of Health

The three primary theoretical directions invoked by

current social epidemiologists, are not mutually

exclusive, can be designated as follows: (1)

psychosocial approaches; (2) social production of

disease/political economy of health; and (3) Eco-

social theory and related multi-level frameworks.

These structural determinants are what we include

when referring to the "social determinants of health

inequities." This concept corresponds to Graham's

notion of the "social processes shaping the

distribution" of downstream social determinants. A

comprehensive SDH framework should achieve the

following: (1) Identify the social determinants of

health and the social determinants of inequities in

health; (2) Show how major determinants relate to

each other; (3) Clarify the mechanisms by which

social determinants generate health inequities; (4)

Provide a framework for evaluating which SDH are

the most important to address and (5) Map specific

levels of intervention and policy entry points for

action on SDH. Health inequities flow from patterns

of social stratification—that is, from the

systematically unequal distribution of power,

prestige, and resources among groups in society

(WHO, 2010).

2.2 Application of the Framework to

Smoke-Free Homes in Indonesia

First Section

2.2.1 Socioeconomic and Political Context

(Macro Level)

Socioeconomic approach: smoking is the most

significant avoidable cause of inequalities in health.

Socio-economically disadvantaged people are more

likely to smoke and have started smoking younger

and smoke more heavily than their less disadvantaged

peers. Uptake may also be higher among those with

low socioeconomic status (SES), and quit attempts

are less likely to succeed. Raising the price of tobacco

products appears to be the tobacco control

intervention with the most potential to reduce health

inequalities from tobacco (Hiscock, Bauld, Amos,

Fidler, & Munafò, 2012). The policies of private and

public entities that limit the opportunities of

underprivileged groups are referred to as structural

discrimination. Restriction occurs as a result of

regulations' intentional or unforeseen repercussions,

with examples of structural discrimination emerging

in the context of the tobacco epidemic (Stuber, Galea,

& Link, 2008). The policies of private and public

entities that limit the opportunities of underprivileged

groups are referred to as structural discrimination.

Restriction occurs as a result of regulations'

intentional or unforeseen repercussions, with

examples of structural discrimination emerging in the

context of the tobacco epidemic (WHO, 2010).

Political approach: The regulator of tobacco in

Indonesia was passed in early 2003. The dates during

which it was debated and signed coincided with a

meeting in Geneva of the Intergovernmental

Negotiating Body (INB) of the Framework

Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). Thus,

senior Ministry of Health and Food and Drug

Administration representatives involved in tobacco

control issues were not present (Achadi, Soerojo, &

Barber, 2005). Indonesia is the only country in Asia

that refused and did not sign FCTC (Sarvika &

Aditama, 2016). Determination of Non-Smoking

Areas should be held in service facilities for health,

place of the learning process, place child play, place

of worship, public transport, workplace, public

places, and other places designated (Indonesia, 2009).

According to Government Regulation (PP) number

109 2012, The No Smoking Area (KTR) in areas

declared prohibited for activities smoking or

activities producing, selling advertising an promoting

products tobacco (RI, 20Indonesia’snesia tobacco

control regulation passed in 1999, succeeded by

amendments in 2000 and 2003. Today, few

restrictions exist on tobacco industry conduct,

advertising, and promotion in Indonesia (Achadi et

al., 2005).

Cultural and societal Values approach: Cultural

belief, tolerance in indoor smoking (Abramova et al.,

2017), socially unacceptable colludes with patriarchy

(Annandale & Clark, 2000), senior family men's

smoking (Mao, 2014), social acceptance, social

bonding, and tradition (Bush, White, Kai, Rankin, &

Bhopal, 2003) and parental value system (Emory,

Saquib, Gilpin, & Pierce, 2010). Widely cultivated

across Java Indonesia, tobacco was added to the long-

established social habit of chewing betel (Achadi et

al., 2005).

ICSDH 2022 - The International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

148

2.2.2 Socioeconomic Situation and

Structural Determinants (Meso

Level)

a. Increased smoking prevention efforts are

needed in low-SES areas, and limiting

adolescents' pocket money may be an effective

strategy for preventing smoking (Unger, Sun, &

Johnson, 2007). Indonesia's cigarette

expenditure spending in 2017 amounts to

Rp.65,586.00 per day (BPS, 2017). Meanwhile,

the cost of cigarette expenditure on low-income

families in the Samarinda City of Indonesia

amounts to 27.45% (Rp.15,759.00) of

household expenses (Rohmah Nur, 2016).

b. Education

In general, low education makes them lack the

correct health information and information

about the dangers of smoking. Adolescent

cigarette smoking was associated with low

school achievement (Conwell et al., 2003). The

proportion of the population in Indonesia at the

education level of 28,7 % active smoking for

senior high school, no educated 22.8% (RI,

2013).

c. Occupation

in smoker groups mainly from the informal

sector, although not denied from the formal and

professional sector many also become smokers.

However, it is related to family expenditure in

the informal sector because almost 25% is spent

on cigarettes. By type of work,

farmers/fishermen/laborers are the most

significant proportion of active smokers each

day in Indonesia; around 44.5%, 9.9 % of

smokers in the group did not work (RI, 2013).

d. Social class

Widening social class inequalities in smoking

prevalence that members of lower social classes

are increasingly more likely to take up smoking

and less likely to quit (London, 1974). Smoking

behavior spreads through close and distant

social ties. The extent to which smoking

depends on how people are embedded in a social

network and how smoking behavior transcends

direct dyadic ties are not known (Christakis &

Fowler, 2008).

e. Gender and Age

The proportion of the population in Indonesia

aged ≥15 years of male smokers is 67.0% in

2011, to 64.9 % in 2013. More men than female

smokers (47.5% and 1.1%). Similarly,

according to GATS (Global Adult Tobacco

Surveys), female smokers are 2,7% in 2011 and

2.1 % (RI, 2013). The most significant

proportion of active smokers in Indonesia every

day is 30-34 years old, 33.4 %, age 35-39 years

32.2% (RI, 2013). Since starting to smoke at an

early age increases the number of cigarettes

smoked per day in adult life, it is likely to

enhance the risk of tobacco-related diseases. In

Samarinda city Indonesia, early ag start

smoking at four years (Rohmah, 2013).

2.2.3 An Intermediary Determinant

(Individual Level)

Social position determines health through

intermediate factors. Material circumstances,

behavioral and biological variables, and

psychological issues are all intermediate

determinants.

a. Material Circumstances

If a family member (like a father, or grandfather)

smokes at home will result in other family

members becoming passive smokers. This

condition is exacerbated if family members

risks, such as infants, toddlers, pregnant women,

and the elderly.

Data on smoking behavior at home in Indonesia

is 21.2% (RI, 2013), the average family member

stays at home 3.9 persons per household in 2015

(BPS, 2017), and smoking is a lifestyle in

Indonesia (Budiarsih & Ngah, 2017).

b. Behavior and biological factors

Behavior factors such as smoking is an essential

determinant of health. Smoking is generally

prevalent among the lower socioeconomic

group. Risk factors tend to cluster in socially

patterned ways. For example, those living in

adverse childhood social circumstances are

more likely to be low weight and be exposed to

poor diet, childhood infections, and passive

smoking (WHO, 2010).

In Indonesia, daily smokers in urban areas

outnumber those in rural areas by 30.4 percent

and 28.3 percent, respectively. Consuming

tobacco 12.8 pieces per day. Asthma 4.5%, lung

disease 3.7% and cancer 1.4% (RI, 2013).

c. Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial factors are highlighted by the

psychosocial theory described above. Relevant

factors include stressors (e.g., adverse life

events), stressful living circumstances, and lack

of social support (WHO, 2010). Psychosocial

Social Determinant of Health for Smoke-Free Homes to Protecting Children Become Smoker (Passive or Active)

149

Figure 1: Applying CSDH Conceptual Framework for Smoke-Free Home in Indonesia Modification CSDH from (WHO,

2010) and (Whitehead & Dahlgren, 1991).

variables from adolescence and young

adulthood were significantly distinguished

among empirically identified four trajectory

groups (early stable smokers, late stable

smokers, experimenters, and quitters) (Chassin,

Presson, Pitts, & Sherman, 2000).

Data Smoking in Indonesian motives relieves

tension and stress occupy the highest order,

which is an average of 37,35 % (Rohman & Psi,

2010).

d. Health System

Indonesia's Ministry of Health has a program.

Individual health efforts are any activities

undertaken by the government, society, and the

private sector. To maintain and improve health

and prevent and cure disease and restore health,

individuals include health promotion efforts,

disease prevention, outpatient treatment,

treatment of hospitalization, restriction, and

recovery defects directed against individuals

(Adisasmito, 2007).

e. Impact on equity in health and well-being

Impact on equity in health and well-being, in

particular, moving away from a focus on

physical health status as measured by mortality

and morbidity to encompass, wherever possible,

many other dimensions of health and well-being

(Whitehead, 1991).

3 DISCUSSIONS

Suppose these children, mostly from minority groups

and impoverished families, had no hope for the future

and difference. Would it make if they smoked or used

drugs, missed school, or engaged in violent behavior?

Among smoking households, restriction types varied

according to the number and gender of parents who

smoke. In both smoking and non-smoking

households, children's SHS exposure was directly

related to the type of home smoking restriction, with

the lowest exposures among those reporting full

restrictions (Akhtar, Haw, Currie, Zachary, & Currie,

2009). Although the primary preventive goal should

be to achieve a smoke-free environment, the finding

of an association between early age at the start of

smoking and heavy subsequent cigarette

consumption suggests that additional efforts should

be made to postpone the beginning of smoking among

youngsters (Taioli & Wynder, 1991). By adopting

strong home smoking bans, parents can reduce some

of the influence friends' smoking can have on the

smoking behavior of their adolescents (Szabo, White,

& Hayman, 2006).

Smokers were indistinguishable from non-

smokers in terms of integration in their social

networks. Nevertheless, three decades later,

reflecting significant shifts in societal views of

smoking, smokers were at the periphery of social

ICSDH 2022 - The International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

150

networks and aligned with other smokers

(Bainbridge, Smith, & Barker, 2008).

Based on these cases caused by smoke pollution

cigarettes at homes, need for guidance and

supervision of non-smoking areas in Indonesia. The

need for a set of rules that can support the creation of

a good environment, healthy and free from tobacco

smoke, and the need for guidance and supervision of

a limited region of cigarettes conducted by the City

Health Office Indonesia.

The government is expected to implement KTR

starting from government offices, including the DPR

by giving sanctions to employees who do not comply

with the rules. Smoking is their right, but they also

have to respect the rules for the crowd, that means in

a non-smoking area there is absolutely no smoke, no

cigarette advertisements and no one sells cigarettes, if

it is still fulfilled then sanctions must be imposed,

considering the sanctions this will deter violators. The

scope of the tobacco-free area is regulated in Law No.

36 of 2009 and Government Regulation No. 109 of

2012, among others, the government stipulates that

facilities that are not allowed to smoke are health

service facilities, places of study, places of worship,

public places and other places where smoking is not

permitted. set.

The Ministry of Health (2014) explained that

tobacco product advertisements are targeted at

teenagers, explained that 80% of Indonesian smokers

start smoking before the age of 19 years, the tobacco

industry aggressively targets young people, both

directly and indirectly. Tobacco advertising increases

consumption among children and youth by creating

an environment in which tobacco use is considered

good and regular.

Studies in 102 countries show that a limited ban

on cigarette advertising has little or no effect on

reducing tobacco consumption. Tobacco Control

Support Center Public Health Association of

Indonesia (TCSC-IAKMI) In collaboration with the

Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA)

and the World Health Organization (WHO) Indonesia

reported the four best policy alternatives for tobacco

control, namely raising taxes (65% from retail prices),

prohibiting all forms of cigarette advertising,

implementing 100% non-smoking areas in public

places, workplaces, places of education, as well as

enlarging smoking warnings and adding images due

to smoking habits on cigarette packs.

For the suggested intervention, we will use the

structural intervention to tackle smoke-free homes in

Indonesia can be explained (see. Table 1).

4 CONCLUSION AND

SUGGESTIONS

A summary that the social determinant of health

should be comprehensively determined from various

levels of macro level, meso level, and individual level

so we can determine the determinants of health,

especially for smoking problems at home.

The biased advice presented in this article is that

there needs to be a holistic strategy for protecting

children from exposure to cigarette smoke in the

home environment, institutes, organizations, and

policymakers.

Table 1: Framework to Structural Intervention for smoke-free homes.

Intervention tar

g

e

t

Source of problem Individual-level Or

g

anization level Environment level

Availability Knowledge about smoking and

health, perceived risk of

smoking-related disease, self-

efficac

y

to refuse a ci

g

arette

Local ordinances

require smoke-free

homes.

Regulation selling cigarettes

by retail and not selling

cigarettes for child

Acceptability Picture by sticker do not smoke

at home

Tobacco product

advertising must

have a visual health

warning on the

p

acka

g

e.

Regulation on violence in the

media such as TV does not

show cigarette advertisements

on primetime and limits

b

illboards on the stree

t

Accessibility to smoke-free homes Zoning and timing

regulation to sell

cigarettes.

Prohibition of single

ci

g

arette sales

Community-based initiation by

health volunteers to reduce

smoking at home

Social Determinant of Health for Smoke-Free Homes to Protecting Children Become Smoker (Passive or Active)

151

REFERENCES

Abramova, Z., Sami, M., & Huh, J. (2017). Involuntary

Tobacco Smoking Exposure Among Korean American

Emerging Adults: A Qualitative Study. Journal of

immigrant and minority health, 19(3), 733-737.

Achadi, A., Soerojo, W., & Barber, S. (2005). The

relevance and prospects of advancing tobacco control

in Indonesia. Health policy, 72(3), 333-349.

Adisasmito, W. (2007). Sistem Kesehatan Nasional.

Jakarta: Rajagrafindi Persada.

Akhtar, P. C., Haw, S. J., Currie, D. B., Zachary, R., &

Currie, C. E. (2009). Smoking restrictions in the home

and secondhand smoke exposure among primary

schoolchildren before and after the introduction of the

Scottish smoke-free legislation. Tobacco Control,

18(5), 409-415.

Annandale, E., & Clark, J. (2000). Gender, postmodernism,

and health. Health, medicine, and society: Key theories,

future agendas, 51-64.

Bainbridge, J., Smith, A., & Barker, S. (2008). Stranded in

the Periphery—The Increasing Marginalization of

Smokers. N Engl J Med, 358, 2231-2239.

Been, J. V., Nurmatov, U. B., Cox, B., Nawrot, T. S., van

Schayck, C. P., & Sheikh, A. (2014). Effect of smoke-

free legislation on perinatal and child health: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet,

383(9928), 1549-1560.

Best, C., Sun, K., De Pee, S., Sari, M., Bloem, M., &

Semba, R. (2008). Paternal smoking and increased risk

of child malnutrition among families in rural Indonesia.

Tobacco Control, 17(1), 38-45.

Blankenship, K. M., Bray, S. J., & Merson, M. H. (2000).

Structural interventions in public health. Aids, 14, S11-

S21.

BPS. (2017). Laporan Sensus Penduduk 2017. Retrieved

from

Budiarsih, B., & Ngah, A. C. (2017). Role of Law

Influences on Modern Lifestyle Issues In Indonesia and

Malaysia. Scientific Journal of PPI-UKM, 4(1), 18-25.

Bush, J., White, M., Kai, J., Rankin, J., & Bhopal, R.

(2003). Understanding influences on smoking in

Bangladeshi and Pakistani adults: a community-based,

qualitative study. BMJ, 326(7396), 962.

Chassin, L., Presson, C. C., Pitts, S. C., & Sherman, S. J.

(2000). The natural history of cigarette smoking from

adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community

sample: multiple trajectories and their psychosocial

correlates. Health Psychology, 19(3), 223.

Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2008). The collective

dynamics of smoking in a large social network. New

England journal of medicine, 358(21), 2249-2258.

Conwell, L., O'callaghan, M., Andersen, M., Bor, W.,

Najman, J., & Williams, G. (2003). Early adolescent

smoking and a web of personal and social disadvantage.

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 39(8), 580-

585.

Emory, K., Saquib, N., Gilpin, E. A., & Pierce, J. P. (2010).

The association between home smoking restrictions and

youth smoking behavior: a review. Tobacco Control,

etc. 2010.035998.

Eng, L., Su, J., Qiu, X., Palepu, P. R., Hon, H., Fadhel, E.,

... & Liu, G. (2014). Second-hand smoke as a predictor

of smoking cessation among lung cancer

survivors. Journal of clinical oncology, 32(6), 564-570.

Hawkins, S. S., & Berkman, L. (2011). Increased tobacco

exposure in older children and its effect on asthma and

ear infections. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(6),

647-650.

Hiscock, R., Bauld, L., Amos, A., Fidler, J. A., & Munafò,

M. (2012). Socioeconomic status and smoking: a

review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences,

1248(1), 107-123.

Pemerintah Indonesia. (2009). Undang-uandang No. 36

Tahun 2009 tentang kesehatan. Sekretariat Negara.

Jakarta

Lee, K.-M., Ward, M. H., Han, S., Ahn, H. S., Kang, H. J.,

Choi, H. S., . . . Choi, J.-E. (2009). Paternal smoking,

genetic polymorphisms in CYP1A1, and childhood

leukemia risk. Leukemia Research, 33(2), 250-258.

Leventhal, H., & Cleary, P. D. (1980). The smoking

problem: a review of the research and theory in

behavioral risk modification. Psychological Bulletin,

88(2), 370.

London, J. F. (1974). Smoking behavior and socioeconomic

status: a cohort analysis, 1974 to 1998. Age, 1984, 1998.

Mao, A. (2014). Getting over the patriarchal barriers:

women's management of men's smoking in Chinese

families. Health education research, 30(1), 13-23.

Olds, R. S., & Thombs, D. L. (2001). The relationship of

adolescent perceptions of peer norms and parent

involvement to cigarette and alcohol use. Journal of

School Health, 71(6), 223-228.

Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. (2013). Riset

kesehatan dasar. Jakarta: Badan Penelitian dan

pengembangan Kesehatan Kementrian Kesehatan RI.

TCSC-IAKMI. 2014. Bunga Rampai : Fakta Tembakau dan

Permasalahannya. Kemenkes RI. Jakarta

Rohmah, N. (2013). Social Learning Theory Application on

Smoking Behavior Junior High School in Samarinda.

Jornal of Sain Learning, 11, No. 4.

Rohmah Nur, R. N., Fitriyana, Exzmy. (2016). Studi

Pengeluaran Biaya Rokok Terhadap Status Gizi Balita

di Kecamatan Samarinda Ulu, Indonesia. Paper

presented at The 3rd Indonesian Conference on

Tobacco or Health 2016, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

http://ictoh-tcscindonesia.com/the-3rd-ictoh-5/

Rohman, A., & Psi, S. (2010). Hubungan Antara Tingkat

Stres dan Status Sosial Ekonomi Orang Tua dengan

Perilaku Merokok Pada Remaja. Diambil Tanggal, 9.

Sarvika, M. A., & Aditama, Y. M. (2016). Indonesia Jadi

Satu-Satunya Negara di Asia yang Menolak FCTC.

tribunnews. Retrieved from http://bogor.

tribunnews.com/2016/10/02/indonesia-jadi-satu-

satunya-negara-di-asia-yang-menolak-fctc.

Semba, R. D., De Pee, S., Sun, K., Best, C. M., Sari, M., &

Bloem, M. W. (2008). Paternal smoking and increased

risk of infant and under-5 child mortality in Indonesia.

American journal of public health, 98(10), 1824-1826.

ICSDH 2022 - The International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

152

Stuber, J., Galea, S., & Link, B. G. (2008). Smoking and the

emergence of a stigmatized social status. Social science

& medicine, 67(3), 420-430.

Szabo, E., White, V., & Hayman, J. (2006). Can home

smoking restrictions influence adolescents' smoking

behaviors if their parents and friends smoke? Addictive

behaviors, 31(12), 2298-2303.

Taioli, E., & Wynder, E. L. (1991). Effect of the age at

which smoking begins on the frequency of smoking in

adulthood. N Engl J Med, 325(13), 968-969.

Thacher, J. D., Gruzieva, O., Pershagen, G., Neuman, Å.,

Wickman, M., Kull, I., . . . Bergström, A. (2014). Pre-

and postnatal exposure to parental smoking and allergic

disease through adolescence. Pediatrics, 134(3), 428-

434.

Unger, J. B., Sun, P., & Johnson, C. A. (2007).

Socioeconomic correlates of smoking among an

ethnically diverse sample of 8

th

-grade adolescents in

Southern California. Preventive Medicine, 44(4), 323-

327.

Wakefield, M., Banham, D., Martin, J., Ruffin, R., McCaul,

K., & Badcock, N. (2000). Restrictions on smoking at

home and urinary cotinine levels among children with

asthma. American journal of preventive medicine,

19(3), 188-192.

White, H. R., Johnson, V., & Buyske, S. (2000). Parental

modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring

alcohol and cigarette use: A growth curve analysis.

Journal of substance abuse, 12(3), 287-310.

Whitehead, M. (1991). The concepts and principles of

equity and health. Health Promotion International,

6(3), 217-228.

Whitehead, M., & Dahlgren, G. (1991). What can be done

about inequalities in health? Lancet, 338(8774), 1059-

1063.

WHO. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the

social determinants of health.

Social Determinant of Health for Smoke-Free Homes to Protecting Children Become Smoker (Passive or Active)

153