The Export Patterns of the Chinese Office Equipment Manufacturing

Industry Using Trade Data of 1984-2019

Yu Hong

1

, Na Li

1

, Lin Zhang

1

and Ting Liu

2

1

College of International Economics and Trade, Jilin University of Economy and Finance, Changchun, China

2

Changchun Humanities and Sciences College, Changchun, China

Keywords: China, Office Equipment Product, Export Patterns.

Abstract: This paper used annual trade data of China's office equipment from 1984 to 2019, and analyzed the export

pattern of office equipment. RSCAX index is used to analyze the comparative advantage of China's office

equipment export, NX index is used to judge the net export ratio of office equipment, and HX index is used

to judge the government intervention of China's office equipment industry. The study found that the

comparative advantage of China's office equipment remained roughly balanced during the sample period,

while the government imposed import restrictions. Although it maintains a trade surplus, its international

competitiveness is still weak.

1 INTRODUCTION

High-tech products as the government's key support

industry more and more attention, office equipment

as one of the gradually into people's life, its trade

status is also gradually improved. The proportion of

China's office equipment in the world's exports has

amounted to 35% of the world's total exports in the

product with large trade surplus.

China has claimed that the Chinese trade policies

are against trade protectionism. The trade surplus,

however, may indicate that China has adopted trade

promotion or import restriction policies in the office

equipment products which are opposite to the free

trade. This paper analyzes the trade pattern of office

equipment in China during the 1984-2019 to explore

the Chinese trade policy in the product. The marginal

contribution this study attempts to make is to reassess

the protectionist supporting trade policy in the

Chinese office equipment manufacturing industry.

2 METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1 Revealed Comparative Advantage

Balassa (1965) proposed the index of revealed

comparative advantage to measure the comparative

advantage of import and export products (Balassa,

1965):

RCAX

co

=(X

co

/X

c

)/(X

wo

/X

w

) (1)

where X represents exports, the subscript of C

indicates China and that of O is for the office

equipment, X

wo

means the global office equipment

exports. RCAX

co

>1 means that China has

comparative advantage in specializing in the office

equipment than the world average; RCA

co

<1mens

the opposite. The value range of RCA

co

is [0, ∞] with

uncertain mean and the distribution is asymmetric

(Hinloopen, 2001).

This study used the logarithmic transformation as

proposed by Dalum, Laursen and Villumsen (1998)

(Dalum, 1998) to obtain the indicator of revealed

symmetric comparative advantage

RX

co

=RSCAX

co

=(RCAX

co

-1)/(RCAX

co

+1) (2)

The range of RX

co

is [-1,1] and distributed around

the mean of 0. RCA

co

>1 generates RX

co

>0 and

denotes comparative advantage; RCA

co

<1

corresponds to RX

co

<0 and shows comparative

disadvantage. RCA

co

=1 exactly implies RX

co

=0,

meaning the specialization is identical to the world

average.

2.2 Net Export Ratio

This research uses the indicator of net export ratio or

126

Hong, Y., Li, N., Zhang, L. and Liu, T.

The Export Patterns of the Chinese Office Equipment Manufacturing Industry Using Trade Data of 1984-2019.

DOI: 10.5220/0011731500003607

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology (ICPDI 2022), pages 126-130

ISBN: 978-989-758-620-0

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

NX

co

=(X

co

-M

co

)/(X

co

+M

co

) (3)

as a benchmark. The range is [-1, 1], and its average

value is 0. NX

co

> 0 implies trade surplus and NX

co

<0

suggests trade deficit. NX

co

=0 means the import is

equal to the export.

2.3 Policy Intervention Index

Under free trade, a country should specialize in and

export the products with comparative advantage and

import those with comparative disadvantage (Lall,

2000; Boone, 2000). RSCA

co

is equal to NX

co

or

RSCA

co

=NX

co

(4)

as the sufficient condition for free trade condition

(Morrow, 2010; Pang, 2010; Hong, Guan, Su, 2012;

Hong, Chen, Yang, 2019). The difference between

NX

co

and RSCA

co

can be understood as the indicator

of policy intervention in export or

HX

co

=NX

co

-RSCAX

co

(5)

The indicator of HX

co

measures the disparity

between net export ability and comparative

advantage in export. Under perfect free trade there

must be HX

co

=0. HX

co

>0 means that the country has

adopted export promotion trade policies, while

HX

co

<0 implies the case of export restriction (Hong,

Yang, Hu, Su, 2019; Hong, Guan, Su, 2013; Hong,

Zhang, Hu, Shi, 2019; Chen, Yu, Hu, Hong, 2019).

HX

co

reflects whether China's net export capacity is

higher or lower than its comparative advantage when

it shows a certain comparative advantage in the

import of products. If the trade pattern is in

equilibrium, there should be HX

co

=0. If HX

co

> 0, then

the net export ratio is greater than the import,

indicating that China has adopted a trade policy to

increase the net export ratio of office equipment by

restricting the import. If HX

co

<0, it means that the

import trade policy adopted by China is not

restrictive, but has the feature of encouraging import

(Hong, Song, Wang, Su, 2014; Hong, Yang, Hu, Shi,

2020; Hong, Chen, Yang, Hu, Ma, 2019; Hong, Yu,

Yang, Hu, Ma, 2020; Hong, Hong, 2016).

2.4 Data Curation

We obtained the annual trade data of 1984-2019 from

UN Comtrade database under the first edition

classification of Standard International Trade (SITC

Rev.1). According to the classification of Revision

one (SITC Rev.1), we found the three-digit code of

714 is for the office equipment. SITC Rev.1 was

employed because of its long sample period (Hong,

Wang, Su, Mu, 2014; Shi, Yang, Hu, Hong, 2019;

Hong, Yu, Yang, Hu, Ma, 2020; Ma, Yang, Yu, Hu,

Hong, 2020; Hong, Zhang, Hu, Ma, 2020).

The 2020 trade data of China and the world can

be available in the later 2021, and some UN member

countries may postpone to report the data. This fact

makes the latest data this current research can obtain

is by the year of 2019.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1

The Evolution of The Chinese

Trade Patterns

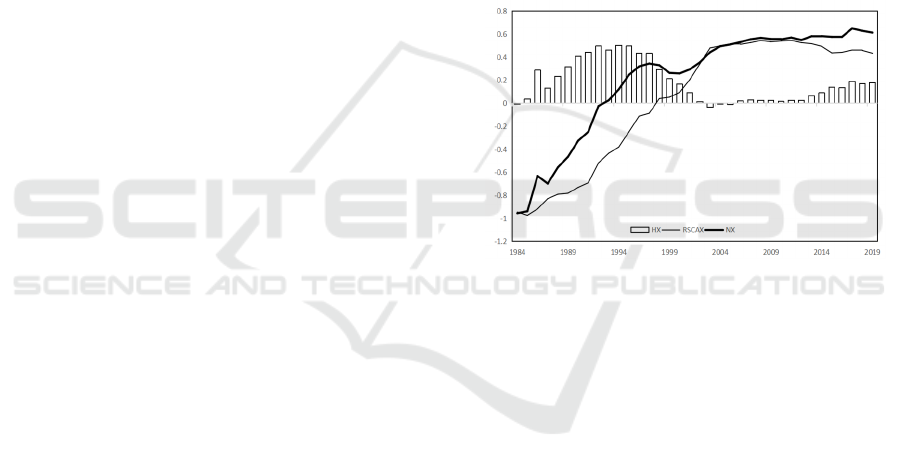

Figure 1 shows the time paths of RSCAX

co

, HX

co

and

NX

co

in China's office equipment export during the

sample period.

Figure 1: Time paths of the Chinese export patterns in the

office equipment (1984-2019).

Firstly, RSCAX

co

showed a downward trend

before 1997, and the index has always been negative.

After 1997, the index turned from negative to

positive and showed an upward trend and gradually

slowed down. After 2014, the index showed a slight

downward trend, but the overall trend was always

positive. The overall trend shows that China's export

of office equipment has turned from a comparative

disadvantage to an advantage and has been

maintained until now.

Secondly, HX

co

basically remained stable during

the sample period. In the 1990s, the value of HX

co

was at its peak. Although the current index has

always been positive, it has not exceeded the

previous value. Except for the negative values from

2003 to 2005, the value of NX

co

in the other years

were basically positive, which means that the

Chinese government's export policy for office

equipment has been mainly to promote export. But

the intensity of the policy has slowed considerably in

recent years, suggesting that China is becoming less

The Export Patterns of the Chinese Office Equipment Manufacturing Industry Using Trade Data of 1984-2019

127

dependent on exports, which may be related to its

economic transformation.

What’s more, the NX

co

index is another group of

data that changes significantly. Before 1992, the

curve was in a negative number with NX

co

<0, but it

gradually increased and approached 0. After 1992,

the NX

co

indicator became positive and kept rising.

During 1999-2000, the index showed a downward

trend, but after that, the index still tended to rise and

remained stable gradually. The change of this index

is similar to the change of RSCAX

co

above.

Table 1 further reports the descriptive statistics of

the Chinese export patterns in the office equipment

industry.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of the Chinese export trade

patterns in the office equipment.

N=36

Minimum Maximum Mean

Standard

Deviation

RX

co

-0.974 0.544 0.020 0.553

HX

co

-0.037 0.501 0.180 0.176

NX

co

-0.957 0.648 0.200 0.480

The results show that the Chinese RSCAX

co

index

reached the minimum value of -0.974 in 1985 and a

maximum value in 2011. The average value is 0.02.

It can be seen from Figure 1 that China's office

equipment has turned from comparative disadvantage

to comparative advantage, with the highest

comparative advantage in 2011 and then gradually

leveling off.

Secondly, HX

co

index reached the lowest in 2003

and the highest in 1994, with an average value of

0.18. This shows that in 1994 China limits the import

of office equipment at the most, while in 2003,

encourages the import of office equipment, but

according to figure 1 we can see that in addition to

special before and after 2003, the rest of the year

China's imports are more restricted for office

equipment, but, in recent years, the limit of strength

is a little reduce than normal.

Finally, the NX

co

index reached its lowest value in

1984 and its highest value in 2017. This indicator

suggests that China is gradually narrowing its trade

deficit in office equipment and encouraging exports

to a trade surplus. The mean value of this indicator

over the sample period was 0.2.

3.2 One Sample T-Test of The Chinese

Export Statistics

Table 2 reports the one-sample t-test results of RX

co

,

NX

co

and HX

co

. The test value is set to zero to test

whether the sample mean is statistically significant

different from 0.

Table 2: One-sample t-test results for the indicators of

RXco, NXco and HXco.

Test

value=0

T-stat

Degree of

freedo

m

Sig.

(2-tailed)

Mean

difference

RX

co

0.216 35 0.830 0.017

NX

co

2.503 35 0.017 0.200

HX

co

6.153 35 0.000 0.180

The t-test results show that the mean of three

indicators are all greater than zero. The significance

of RSCAX

co

is 0.830, being statistically

insignificantly different from 0. This fact shows that

China has no comparative advantage in the export of

office equipment. On the other hand, the indicators of

NX

co

and HX

co

are both positive and significant at

0.05 level, implying that China has gained trade

surplus in the trade of the office equipment by t

export promotion. Note that China has no significant

comparative advantage in this product, our findings

indicate that China has adopted protectionist

industrial policies as other countries have done

(Farzin, 1998; Pierce, 1974; Arita, 2017; Costinot,

2012).

3.3 Discussion

The results that China has been export promoting is

not confined to the office equipment manufacturing

industry. Previous studies found plenty evidence that

the Chinese government has deliberately promoted

the export in most products in the trade of goods such

as the primary products (Hong, Dong, Mu, 2018),

agricultural products (Hong, Su, 2010; Hong, Yin,

Yang, Mu, 2018; Hong, Yin, Ren, Mu, 2018), energy

products (Hong, Su, 2011; Hong, Chen, Yang, Liu),

low-technology products (Hong, Ren, Shao, Mu,

2018; Hong, Ren, Yin, Mu, 2018), as well as the

high-technology products (Hong, Qu, Wang, Liu,

2021; Hong, Zhang, Li, Liu, 2021). The puzzle is that

there are both comparative advantaged and

comparative disadvantaged products or industries.

For the office equipment manufacturing industry,

China has rather been comparative advantaged

although the comparative advantage is insignificant.

Our findings are consistent to the previous

studies. The above mentioned studies imply that the

Chinese trade promotion policy intervention has not

mainly target at improving the comparative

advantage of the products or the industries.

Comparative advantage of a product or an industry

can largely reveal the technology besides the factor

ICPDI 2022 - International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology

128

endowment of labor and capital. The evolution of the

degree of the comparative advantage can be also

understood as the changes in a country’s independent

R&D ability, which may be crucial to the long-term

development of the office equipment manufacturing

industry.

The Chinese government may promote the export

in the office equipment products to support the

industry in afraid of losing its tiny comparative

advantage, or the main purpose has been the trade

surplus which can facilitate the Chinese employment

and help to improve the Chinese economic growth.

This does not necessarily mean that the Chinese

export promotion has not been interactively

connected to the comparative advantage in the office

equipment industry. The nexus, however, need to be

explored by further econometric analysis instead of

mere observation and guess.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This paper analyzed the revealed symmetric

comparative advantage (RX), the net export ratio

(NX) as well as the indicator of policy intervention

index (HX) of the Chinese trade in the office

equipment products by using the annual trade data

from the year of 1984 to 2019.

We documented that China has not been

significantly comparative advantaged in the export of

the office equipment but the trade surplus is

significant (p=0.017), which reflects that China has

deliberately promote the export of the product. This

can be explained by the Chinese relatively poor

independent R&D ability, which has made the

country to be specialized in the low-end of the

industrial chain. This study argues that China has

adopted protectionist export promotion policies in the

export of office equipment.

The effects of the trade (export) policy

intervention upon the Chinese comparative

advantage in the product, however, requires further

econometric analysis in order to provide the

empirical evidence. What is more, this study focused

on the export patterns of the Chinese office

equipment products. The policy intervention that

revealed in the Chinese import patterns requires

another independent study instead of the simple

assumption.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was financially supported by Jilin

Provincial Social Science Fund (2020J58, 2020J60)

and Changchun Social Science Fund (CSK2020ZYJ-

001) and the College Poverty Stricken Students

Supporting Programme funded by Jilin Provincial

Ecological Industry Company Limited.

REFERENCES

A. Costinot, D. Donaldson, I. Komunjer, “What goods do

countries trade? a quantitative exploration of ricardo's

ideas,” Rev. Econ. Stud., vol. 79 (2), 2012, pp. 581-

608.

B. Balassa, “Trade liberalisation and "revealed"

comparative advantage 1,” Manchester Sch., vol. 33

(2), 1965, pp. 99-123.

B. Dalum, K. Laursen, G. Villumsen, “Structural change

in OECD export specialisation patterns: de-

specialisation and 'stickiness',” Int. Rev. Appl. Econ.,

vol. 12 (3), 1998, pp. 423-443.

C. J. Chen, K. X. Yu, A. J. Hu, Y. Hong, “How does the

import restriction Granger cause the comparative

advantage of the USA ' s fossil energy imports?,”

Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol., vol.126 (S4), 2019,

pp. 307.

D. Pang, Y. Hong, “Measuring distortions of trade

patterns: an application to China,” IEEE International

Conference on Service Operations and Logistics and

Informatics (SOLI 2010), 2010, pp. 424-429.

G. Shi, Y. M. Yang, A. J. Hu, Y. Hong, “Assessing the

effectiveness of the import restriction on improving

the Israeli services export comparative advantage,”

Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol., vol. 126 (S4), 2019,

pp. 342-343.

J. Hinloopen, C. V. Marrewijk, “On the empirical

distribution of the balassa index,” Rev. World Econ.,

vol. 137 (1), 2001, pp. 1-35.

J. Boone, “Competitive pressure: the effects on

investments in product and process innovation,” The

Rand J. Econ., vol. 31 (3), 2000, pp. 549-569.

J. L. Pierce, J. J. Enzler, “The effects of external

inflationary shocks”, Brooking Papers Econ. Activity,

vol. 5 (1), 1974, pp. 13-61.

P. M. Morrow, “Ricardian–Heckscher–Ohlin comparative

advantage: Theory and evidence,” J Int. Econ., vol. 82,

2010, pp. 37-151.

P. Ma, Y. M. Yang, K. X. Yu, A. J. Hu, Y. Hong, “How

have the degree of import restriction impacted Japan's

revealed comparative advantage in the services

exports?,” Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol., vol. 126

(S1), 2020, pp. 121.

Q. Hong, Y. Hong, “Does Japan limit its imports for

comparative advantage reasons?-the case of

agricultural manufactures,” 2016 3rd International

Conference on Social Science, 2016, pp. 497-501.

The Export Patterns of the Chinese Office Equipment Manufacturing Industry Using Trade Data of 1984-2019

129

S. Arita, J. Beckman, L. Mitchell, “Reducing transatlantic

barriers on U.S.-EU agri-food trade: what are the

possible gains?,” Food Policy, vol. 68 (1), 2017, pp.

233-247.

S. Lall, “The technological structure and performance of

developing country manufactured exports, 1985–98,”

Oxford Development Stud., vol. 28 (3), 2000, pp. 337-

369.

Y. Hong, J. Guan, H. Su, “Can export facilitation improve

Chinese comparative advantage? panel Granger

causality tests using data of 1982-2011 trade in

services,” Adv. Inform. Sci. Serv. Sci., vol. 4 (19),

2012, pp. 296-303.

Y. Hong, C. J. Chen, Y. M. Yang, A. J. Hu, “Granger

causality between Korea's net export and the

comparative advantage in the exports of electro

medical and x- ray apparatus,” Basic Clin. Pharmacol.

Toxicol., vol. 126 (S4), 2019, pp. 52.

Y. Hong, Y. M. Yang, A. J. Hu, H. W. Su, “Exploring

Granger non-causality of the Japanese employment

rate and the trade in services,” Adv. Soc. Sci. Edu.

Hum. Res, vol. 357, 2019, pp. 140-144.

Y. Hong, J. Guan, H. Su, “How does chinese trade pattern

in goods diverge from equilibrium? an empirical

examination using data of 1987-2011,” Adv. Inform.

Sci. Serv. Sci., vol. 5 (2), 2013, pp. 352-360.

Y. Hong, X. Y. Zhang, A. J. Hu, G. Shi, “The export

promotion and the comparative advantage in Israel's

trade of the primary agricultural products,” Basic Clin.

Pharmacol. Toxicol., vol. 126 (S4), 2019, pp. 307-308.

Y. Hong, Z. Song, J. Y. Wang, H. W. Su, “Comparative

advantage of food exports, rural-urban income

disparity and agricultural employment: empirical

evidence from China,” Pharm. Res., vol. 6 (1), 2014,

pp. 439-445.

Y. Hong, M. X. Yang, A. J. Hu, G. Shi, “Examining

Granger causal relationship between the USA's export

promotion and comparative advantage of

telecommunication products using a more

sophisticated weighting,” Basic Clin. Pharmacol.

Toxicol., vol. 126 (S4), 2020, pp. 317-318.

Y. Hong, C. J. Chen, Y. M. Yang, A. J. Hu, P. Ma,

“Granger causality between Korea's net export and the

comparative advantage in the exports of electro

medical and x- ray apparatus,” Basic Clin. Pharmacol.

Toxicol., vol. 126 (S4), 2019, pp. 48.

Y. Hong, K. X. Yu, Y. M. Yang, A. J. Hu, P. Ma, “The

United States’ export promotion and comparative

advantage in the trade of medicinal and

pharmaceutical products: 1962-2018,” Basic Clin.

Pharmacol. Toxicol, vol. 126 (S4), 2020, pp. 56-56.

Y. Hong, J. Wang, H. Su, X. Mu, “Panel cointegration

analysis of export facilitation and comparative

advantages: the case of Chinese low-technology

manufactures,” Bio Technology: an Indian J., vol. 10

2014, pp. 6040-6048.

Y. Hong, K. X. Yu, Y. M. Yang, A. J. Hu, P. Ma,

“Exploring Granger causality of China's policies of

export promotion and import restriction in the

medicinal and pharmaceutical products,” Basic Clin.

Pharmacol. Toxicol., vol. 126(S4), 2020, pp. 61-62.

Y. Hong, X. Y. Zhang, A. J. Hu, P. Ma, “Econometric

znalysis of the Israeli Trade protectionism and the

export comparative advantage of the primary

agricultural products,” Basic Clin. Pharmacol.

Toxicol., vol.126 (S4), 2020, pp. 305-306.

Y. H. Farzin, K. J. M. Huisman, P. M. Kort, “Optimal

timing of technology adoption,” J. Econ. Dynamics

Control, vol. 22, 1998, pp. 779-799.

Y. Hong, W. J. Dong, X. W. Mu, “The distortion of the

trade patterns in the U.S. primary products,” DEStech

Transactions on Social Science Education and Human

Science, (March), 2018,

doi:10.12783/dtssehs/icems2018/20187.

Y. Hong, H.W. Su, “Can strategic trade policies improve

comparative advantages of exports? a heterogeneous

panel analysis of Chinese agro based manufactures,”

Proceedings of 2010 International Colloquium on

Computing, Communication, Control, and

Management (CCCM2010), 2010, pp. 652-655.

Y. Hong, Z. M. Yin, Y. M. Yang, X. W. Mu, “Assessing

the trade policy of the U.S. agro-Imports,” 2018

International Conference on Mathematics, Modeling,

Simulation and Statistics Application (MMSSA2018),

2018, pp. 155-158.

Y. Hong, Z. M. Yin, S. S. Ren, X. W. Mu, “How far are

the U.S. agro-imports distorted away from free

trade?,” 2018 5th ERMI International Conference on

Art, Education and Social Sciences (ERMI-AES

2018), 2018, pp. 470-475.

Y. Hong, H. W. Su, “Tight energy supply constraints and

technological progress,” Energy Procedia, vol.11,

2011, pp. 3151-3156.

Y. Hong, C. J. Chen, D. Yang, T. Liu. “Short-run and

long-run Granger causality analysis of the United

Kingdom’s trade patterns in the fossil energy trade,”

IOP Conference Series 702 012008, doi:10.1088/1755-

1315/702/1/012008.

Y. Hong, S.S. Ren, B. N. Shao, X.W. Mu. “A

comparative analysis on the export and import trade

patterns of the Chinese low-technology manufactures,”

2018 3rd PIL International Conference on Business,

Social Sciences and Information Science (PIL-BSI

2018), 2018, pp. 78-83.

Y. Hong, S.S. Ren, Z. M. Yin, X. W. Mu, “Exploring the

Chinese import policy on the low-technology

manufactures of garments, textiles and footwear,”

DEStech Transactions on Social Science Education

and Human Science (March) (2018),

doi:10.12783/dtssehs/ichss2017/19555.

Y. Hong, B. B. Qu, Y. Wang, T. Liu, “A comparative

analysis on the import and export trade patterns of

China's mechanical and electrical products,” IOP

Conference Series 1978 (2021) 012064,

doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1978/1/012064.

Y. Hong, L. Zhang, N. Li, T. Liu, “Empirical analysis on

the export trade patterns in the Chinese antibiotic

products,” IOP Conference Series 1978 (2021)

012046, doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1978/1/01204.

ICPDI 2022 - International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology

130