Analysis on the Determining Factors of International Tourism in New

Zealand: Optimisation of Computer-based Algorithmic Linear

Regression Model

Hewei

Chang

Surrey International Institute, Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, China

Keywords: International Tourism, New Zealand, Linear Regression Model, The Elasticity of Demand.

Abstract: Scientific tourism management is becoming increasingly significant. Hence, this paper utilizes computer-

optimized methods to ensure and analyse the several factors influencing the demand for international tourism

in New Zealand from macro and microeconomic perspectives. Moreover, this paper utilizes the 'push' and

'pull' theory with variables from the country of origin as push factors and variables from the destination

country as pull factors. Then, data related to the top three source countries from 2009 to 2018 is selected, and

Minitab are utilized for correlation analysis, the best subset, and a linear regression equation so that price

elasticities of demand are calculated for the variables relating to each of the top three sources countries. The

price elasticity of demand is used to show pull factors for stakeholders in the tourism industry and to promote

sustainable international tourism development in New Zealand.

1 INTRODUCTION

Tourism has become a fast-growing and

interconnected branch of the economy (Bunghez,

2016), especially inbound tourism (Li et al., 2018).

Given the positive economic contribution of

international tourists, investigating the influence of

variable factors on the demand of international

tourists and applying them to guide the improvement

of the inbound tourism strategy is vital.

This paper uses the push-pull theory in tourism to

explain how factors in source and destination

countries affect international. By arranging the

literature from both macroeconomic and

microeconomic perspectives, several variables are

identified that can potentially affect tourist arrivals in

New Zealand. Then by establishing a linear

regression equation to study the correlation and

elasticity of various variables with the number of

inbound tourists to New Zealand, the paper explores

the sensitivity between the relative changes in

tourism demand and impact indicators such as price

(Peng et al., 2015).

This study selects New Zealand as the destination.

Among tourist source countries, Australia, China,

and The United States are the top three ones from

2009 to 2018. Tourism has been a major driver of

economic growth in New Zealand (Shu et al., 2014).

Modelling the influencing factors of tourism demand

fosters the growth momentum of the industry in New

Zealand (Pham et al., 2017).

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Variables

Demand stems from economics, including desire and

purchasing power. In the tourism industry, it is

considered to be a measure of the use of a commodity

or service by tourists (Frechtling, 2001). Namely, the

factors affecting the demand for international

inbound tourism influence consumers' judgment and

choice of destinations, which is implied in the

number of arrivals.

In economics, price is one of them, which can be

reflected by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). CPI of

destination and competitive countries are both

crucial. Australia is the latter one. There is a spillover

effect on tourism demand in Australia and New

Zealand (Balli and Tsui, 2016). Spillover effects refer

to an organization's performance of an activity, which

produces the expected effect of the activity, and

unexpected one outside the organization (Li et al.,

588

Chang, H.

Analysis on the Determining Factors of International Tourism in New Zealand Optimisation of Computer-Based Algorithmic Linear Regression Model.

DOI: 10.5220/0011752500003607

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology (ICPDI 2022), pages 588-595

ISBN: 978-989-758-620-0

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

2011). The demand for inbound tourists from New

Zealand can be affected by the Australian tourism

demand factors. Therefore, there may be

complementary or substitutional relationships

between other source countries’ tourism demand for

New Zealand and Australia.

The Exchange rate is an important factor.

Fluctuations in exchange rates dominate changes in

overall relative tourism prices over time (Chang, Hsu,

and McAleer, 2013). Personal disposable income

(PDI) can be used as an index of reflected income and

consuming ability; Gross National Income (GNI) has

a significant impact on a country's international

tourism demand (Khoshnevis and Khanalizadeh,

2017). According to OECD, GNI is based on GDP.

Therefore, GNI and GDP are selected as variables in

this paper; The Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) is

a measure of the attitude of consumers about their

expected financial situation (Dominitz and Charles,

2004), so CCI can affect the travel demand of

consumers by predicting their future income (Easaw,

Garratt, and Heravi, 2005); The Economic policy

uncertainties (EPU) index reflects the uncertainty of

the country's overall economy (Tsui et al., 2018). It

can affect visitors’ confidence in trade and business

activities, thus influencing the demand for business

travel (Tsui et al., 2018); Additionally, price level

indices are the proportion of purchasing power parity

to the market exchange rate. It can identify the

stability of the economic environment in the

destination, which customers care about.

The development of air infrastructure can make it

easier for tourists to reach their destinations (Kanwal

et al., 2020), so people may consider it before

traveling; The increase in crime rate causes

destinations to be troubled by the negative image,

causing the number of tourists to drop significantly

(Lorde and Jackman, 2013); Carbon emissions

reduce the visiting of tourists with a strong awareness

of sustainable development (Chen, Lin, and Hsu,

2017).

2.2 Push and Pull Theory

The mentioned factors can play an important role as

motivations in consumer behavior when deciding on

a destination. The push and pull framework is a valid

approach to testing tourist behavior in tourism theory

(Chen and Chen, 2015). The 'push-pull theory' was

initially one of the key theories in the study of mobile

populations and migration. Gradually, it has been

applied by scholars to study the push and pull factors

that influence tourists' choice of destination, as it is

an efficient way to explain tourists' choice of

destination. In tourism, push factors are understood

as what tourists will choose one place over another.

They are primarily demand-side. Those considered in

this study are GNI, CCI, and PDI in source countries.

Pull factors such as features, attractions, or attributes

of the destination itself. It is primarily an external

factor and belongs to the supply side (Prayag and

Ryan, 2011). They are price level indices, carbon

dioxide emissions, EPU index, CPI, crime rate,

airport construction investment, and exchange rate in

New Zealand.

2.3 Price Elasticity of Demand

Calculating the elasticity of demand for these factors

can better reflect the degree of influence. For

example, the price elasticity of demand at the

destination, the price elasticity of substitution in a

competitive market, and the income elasticity. From

this, the percentage change of the corresponding

independent variable caused by every 1% change in

demand can be analyzed (Tribe, 2020). This has

important implications for the marketing strategy,

pricing, and future tourism demand for destination

tourism products and services (Konovalova and

Vidishcheva, 2013).

3 DATA SOURCES

3.1 Dependent Variables

Tourism demand in the study is shown by the number

of arrivals, including all visitor numbers as well as

arrivals from the top three source countries.

3.2 Independent Variables

In this study, independent variables include price

level indices, investment and maintenance in air

infrastructure, crime rate, three source countries’

GNI, exchange rate, PDI, and CPI- New Zealand,

CPI-Australia, EPU index, and carbon dioxide

emissions.

4 METHODOLOGY

Tourism demand elasticity is a unitless measure of

the sensitivity of tourism demand to changes in

relevant factors (Song et al., 2010), which is simply a

measure of how tourism demand varies with changes

in its influencing factors. The study of tourism

Analysis on the Determining Factors of International Tourism in New Zealand Optimisation of Computer-Based Algorithmic Linear

Regression Model

589

demand elasticity has two main implications: 1. to

understand the changes in tourist tourism demand by

each influencing factor. 2. to assist the destination to

adjust the prices of tourism products and marketing

strategies to maximize revenue based on the results

of this study (Tang and Chen, 2017). If the price of

the destination decreases, tourists' income is

sufficient to purchase and enjoy more tourism

products, but the demand for tourism products in

alternative countries will reduce because they lose

price competitiveness. These two changes are called

the income effect and substitution effect respectively

(Song, et al., 2010). These two effects can be implied

from the values of income and price elasticities in the

demand function. Hence, this paper uses correlation

and regression analysis to analyse the sensitivity of

New Zealand’s inbound tourism demand to changes

in the influencing factors in the Australian, US, and

Chinese markets from the perspective of demand

elasticity. The elasticity of demand is expressed as

follows:

In this paper, the New Zealand arrivals from

Australia, China, and the USA are used as the

dependent variable (Y) respectively. The multiple

linear regression analysis is used to explore the

factors influencing the demand for inbound tourism

in New Zealand and to establish independent

regression equations for the three source countries.

Independent variables such as GNI, CPI, and PDI are

expressed as X

1

, X

2

, X

3

...... are expressed and the

linear model expressions are as follows.

Y=a+ b

1

X

1

+ b

2

X

2

+…+b

n

X

n

Firstly, the study uses Minitab software to

perform correlation analysis for each variable and

screened out the variables with r values greater than

0.8. The independent and dependent variables with

strong correlations were then calculated using

stepwise regression. Although the results obtained

were a good fit, some factors that are highly

correlated in the relevant literature did not enter the

equation. Because this is a purely statistical

screening, the ‘potential’ explanatory power of many

independent variables may be wasted. Therefore, to

fully utilize and analyze all independent variables,

the paper concludes with a method to select the best

subset for the study. Since there was a problem of

excessive covariance in the first equation

establishment, individual variables were excluded

and then regressed. The equations obtained afterward

fit well, and the adjusted r-squared is above 90%, the

equation has passed the F test, P test, and Chi-square

test, proving that the equations meet the requirements

of linear regression.

5 RESULTS

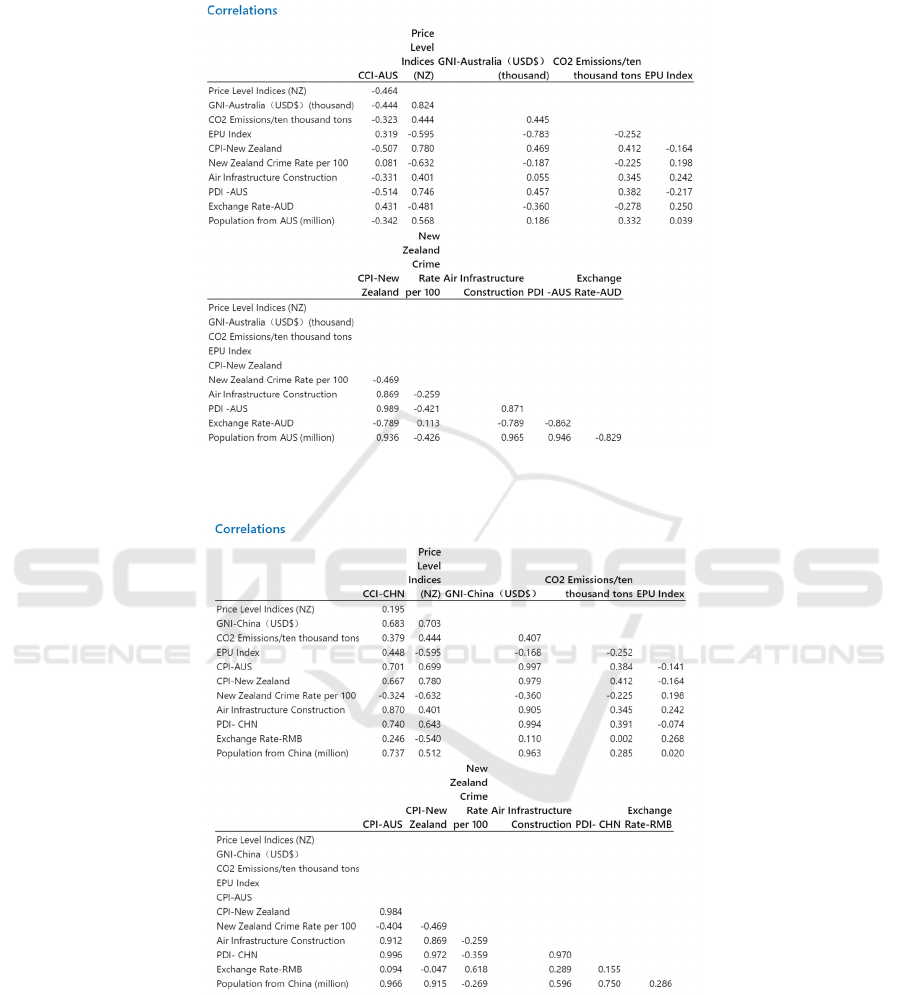

The correlation analysis results are shown in the

following tables by Minitab.

Figure 1: Conceptual Model Diagram.

ICPDI 2022 - International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology

590

Table 1: Correlations of variables of Australia.

AUS

Table 2: Correlations of variables of China.

China

Analysis on the Determining Factors of International Tourism in New Zealand Optimisation of Computer-Based Algorithmic Linear

Regression Model

591

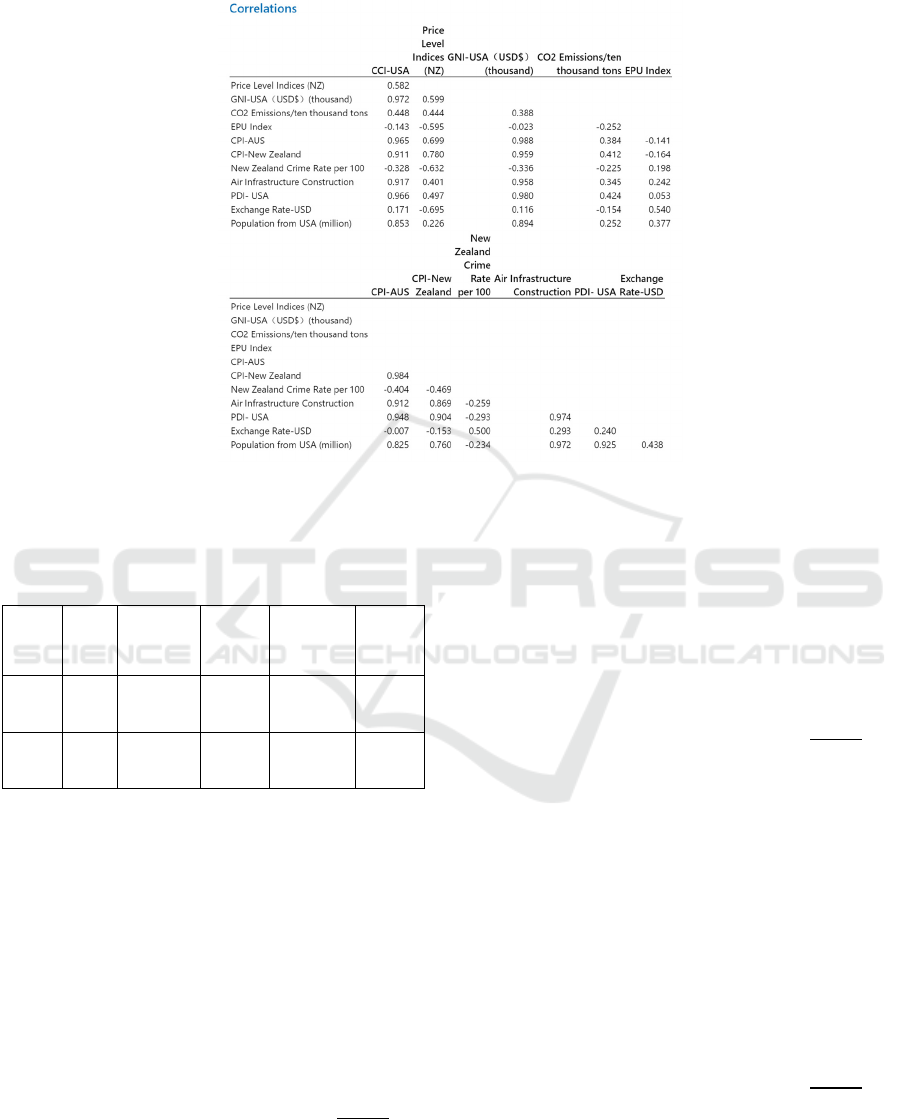

Table 3: Correlations of variables of United States.

USA

After correlation analysis, several factors which are

correlated with the three countries’ tourism demand

are selected in the following table.

Table 4: Factors correlated with tourism demand.

Australia CPI-

New

Zealand

Investment

and

Maintenance

in Airport

Infrastructure

Disposable

Income-

USA

China GNI-

China

CPI-New

Zealand

CPI-AUS Investment in

Air

Infrastructure

Personal

Disposable

Income-

CHN

United

States

CCI-

USA

GNI-USA CPI-AUS Investment in

Air

Infrastructure

Personal

Disposable

Income-

USA

Price of Elasticity of Demand

After using best subset, factors that can significantly

affect tourism demand are selected and then the linear

regression is shown, which has been checked.

1. For the Australian Market:

(1) The Demand Model is below:

Quantity demanded

x

= 2.31+ 1.251*Disposable

Income- AUS+ 8.03* Investment and Maintenance in

Air Infrastructure

After calculating: Quantity demanded

x

=

14,927,948

(2) The Formula needed to Calculate Elasticity:

Price Elasticity of Demand = beta *

Price

Quantity

Results of price elasticity of demand:

Quantity demanded: Price Elasticity of Demand=

0.844

D

x

: Price Elasticity of Demand = 0.104

I

x

: Price Elasticity of Demand = 0.297

2. For the China Market:

(1) The demand model is below:

Quantity demanded

x

= −1.913+ 3.84 * Investment

and Maintenance in Air Infrastructure +0.1385 *

Personal Disposable Income- CHN

After calculating: Quantity demanded

x

=

3,000,088

(2) The formula needed to calculate elasticity:

Price Elasticity of Demand = beta *

Price

Quantity

Results of price elasticity of demand:

Quantity demanded: Price Elasticity of Demand=

0.581

I

x

: Price Elasticity of Demand = 1.056

P

x

: Price Elasticity of Demand = 1.666

3. For the USA Market:

(1) The demand model is below:

Quantity demanded

x

= 5.51+0.0988* CPI-AUS +

5.21* Investment and Maintenance in Air

Infrastructure + 0.119* GNI-USA

After calculating: Quantity demanded

x

=

2,762,046

(2) The formula needed to Calculate Elasticity:

Price Elasticity of Demand = beta *

Price

Quantity

Results of price elasticity of demand:

Quantity demanded: Price Elasticity of Demand=

0.614

C

x

: Price Elasticity of Demand = 3.206

ICPDI 2022 - International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology

592

I

x

: Price Elasticity of Demand = 0.494

G

x

: Price Elasticity of Demand= 2.089

6 DISCUSSION

6.1 PDI

From the obtained elasticity results (1.666), China’s

demand responds to the change in PDI positively.

The elasticity is greater than 1, indicating that the

growth rate of demand is greater than the growth rate

of income. That means New Zealand tourism is a

luxury for Chinese tourists. Such change in

consumers' propensity to consume due to a change in

income is consistent with the income effect in

economics (Jiang and Tang, 2001). In the push and

pull theory, it is regarded as a pull factor to drive

tourists to travel to New Zealand.

6.2 GNI

Based on the results, it can be found that the USA’s

per capita GNI elasticity is 2.089, which means that

the per capita national income of the USA has a

greater impact on the outbound tourism of USA

residents to New Zealand. However, The United

States is a developed country, and traveling abroad is

not a luxury consumption activity for its residents.

This is an interesting finding given that USA GNI is

not supposed to have much impact on outbound

tourism demand.

6.3 CPI

The elasticity of demand of Australia's CPI to the

USA is 3.206, which shows that Australia's CPI

greatly affects Americans' demand for New Zealand

travel. the positive cross elasticity means Australia

and New Zealand are substitute countries for visitors

from America. From the perspective of the

substitution effect, if tourists have lower spending

power than before in Australia, they tend to reduce

demand and increase tourism demand for alternative

New Zealand. From the perspective of income effect,

that means a decrease in the relative income of

tourists, so they will reduce tourism demand,

including in New Zealand. However, the substitution

effect outweighs the income effect, so demand in

New Zealand rises. When Australia's CPI grows, the

USA tends to increase tourism demand in New

Zealand.

6.4 Investment and Maintenance in Air

Infrastructure

The price of elasticity of Australia’s demand is the

least among the three countries. Aviation traffic has

been developed and convenient, and the current

condition has been able to meet the entry demand of

New Zealand tourists (Duval, 2013). The

maintenance and upgrade of the airport facilities will

not affect their entry. As a result, there is little

elasticity.

However, the figure of China is 1.056, which is

relatively elastic. According to this, Chinese tourists

are sensitive to airport infrastructure investment.

Investment in airport infrastructure can increase

passenger traffic, provide more services, and increase

airfares (Eugenio-Martin, 2016). Due to the small

number of flights between New Zealand and China,

it is difficult to meet the increasing demand from

China (Ozer, Balli, and Tsui, 2018). Thus, an increase

in airport accessibility can pull significant increasing

Chinese tourism demand. As air traffic between the

two countries matures, the index may become less in

the future.

The price elasticity of demand in the USA is equal

to 0.494, which is inelastic. One of the reasons is that

America is more accessible to New Zealand than

China. Additionally, due to their higher PDI, USA

travellers are less sensitive to the increased airfare

caused by the investment in air infrastructure than

Chinese travellers (Schiff and Becken, 2011).

Therefore, the pulling power is not as strong as that

of the Chinese.

Overall, the elasticity of demand for long-

distance transportation is greater than that for short-

distance transportation. It can be attributed that

people traveling long distances have higher

requirements for service and put more emphasis on

the convenience of air infrastructure (Wu et al.,

2020). Therefore, China and USA pay more attention

to air investment and construction than Australia.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This study mainly uses the push-pull theory to study

the influencing factors and price elasticity of

Australia, China, and the United States' demand for

New Zealand's international tourism. Research shows

that Australia and China are less price-sensitive,

while the US is more resilient. Changes in PDI and

CPI will also have a greater impact on New Zealand's

inbound tourism demand. In addition, due to the

special geographical location of New Zealand,

Analysis on the Determining Factors of International Tourism in New Zealand Optimisation of Computer-Based Algorithmic Linear

Regression Model

593

aviation infrastructure will directly affect the number

of arrivals, so air services should be improved.

This study only considers economic and

environmental factors and does not consider political

and cultural factors, which may affect international

tourism (Cheung and Saha, 2015). Beyond that, the

findings of this study are not generalizable because

the research only collects tourism data from New

Zealand for 10 years, and the short-term fluctuations

and lags of variables are not observable (Nghiem,

Pham, and Dwyer, 2017). Therefore, there may be

errors between the findings and the actual situation.

REFERENCES

Bunghez, C. L. (2016) ‘The importance of tourism to a

destination’s economy, Journal of Eastern Europe

Research in Business and Economics 2016(1) pp. 1-9.

doi.10.5171/2016.143495

Balli, F. and Tsui, W. H. K. (2016) ‘Tourism Demand

Spillovers between Australia and New Zealand:

Evidence from the Partner Countries’, Journal of travel

research 55 (6), pp. 804–812

doi.10.1177/0047287515569778

Chang C-L, Hsu H-K, and McAleer, M. (2013) ‘Is small

beautiful? Size effects of volatility spillovers for firm

performance and exchange rates in tourism’, The North

American Journal of Economics and Finance 26(1) pp.

519–534.

Chen, C. M., Lin, Y. L., and Hsu, C. L. (2017) ‘Does air

pollution drive away tourists? A case study of the Sun

Moon Lake National Scenic Area’, Taiwan.

Transportation Research Part D: Transport and

Environment 53(1) pp. 398-

402.doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.04.028.

Chen, L.-J. and Chen, W.-P. (2015) ‘Push-pull factors in

international birders’ travel’, Tourism Management

48(2) pp. 416–425.

Cheung, Y. H. (Yh) and Saha, S. (2015) Exploring the Nexus

Between Tourism Demand and Cultural Similarity.

Tourism analysis. [Online] 20 (2), 229–241. (Accessed:

13

th

Apr 2022)

Dominitz, J. and Charles, F. M. (2004) ‘How Should We

Measure Consumer Confidence?’, Journal of Economic

Perspectives 18(2) pp. 51-66.

Duval, D.T. (2013) ‘Critical Issues in Air Transport and

Tourism, Tourism Geographies 15(3) pp. 494–510.

Easaw, J.Z., Garratt, D. and Heravi, S.M. (2005) ‘Does

consumer sentiment accurately forecast UK household

consumption? Are there any comparisons to be made

with the US?’, Journal of Macroeconomics 27 (3)

pp.517-32?

Eugenio-Martin, J. L. (2016) ‘Estimating the Tourism

Demand Impact of Public Infrastructure Investment:

The Case of Malaga Airport Expansion’, Tourism

Economics 22(2) pp. 254–268.

Frechtling, D. C. (2001) Forecasting tourism demand

methods and strategies Oxford: Butterworth-

Heinemann.

Jiang, H., and Tang Y. E. (2001) ‘Research on Price

Elasticity of Demand in Tourism Economy’, Journal of

Beijing International Studies University 1(3) pp. 1-6.

Khoshnevis, Y. S. and Khanalizadeh, B. (2017) ‘Tourism

demand: a panel data approach, Current issues in

tourism, 20 (8), pp. 787–800.

Kanwal, S., Rasheed, M. I., Pitafi, A. H., Pitafi, A., and

Ren, Minglun (2020) ‘Road and transport

infrastructure development and community support for

tourism: The role of perceived benefits, and community

satisfaction, Tourism management (1982) doi.10.1016

/j.tourman.2019.104014.

Konovalova, A.A., and Vidishcheva, V.E. (2013)

‘Elasticity of Demand in Tourism and Hospitality,

European Journal of Economic Studies, 4(2), pp. 84-89

(Accessed on 10

th

Apr 2021).

Li, K. X., Jin, M. and Shi, W. (2018) ‘Tourism as an

important impetus to promoting economic growth: A

critical review’, Tourism management perspectives,

26(1) pp. 135–142 doi.10.1016/j.tmp.2017.10.002.

Li, S., Min, X., Kun, Z., Jing, W., and Zheng, W. (2011).

‘Measuring Tourism Spillover Effects among Cities:

Improvement of the Gap Model and a Case Study of the

Yangtze River Delta’, Journal of China Tourism

Research, 7 (2), pp. 184-206.

Lorde, T. and Jackman, M. (2013) ‘Evaluating the Impact

of Crime on Tourism in Barbados: A Transfer Function

Approach’, Tourism analysis 18 (2) pp. 183–191.

Ozer, B.H., Balli, F. and Tsui, W.H.K. (2018)

‘International tourism demand, number of airline seats

and trade triangle: Evidence from New Zealand

partners’, Tourism Economics 25(1) pp. 132–144.

Peng, B., Song, H., Crouch, G. I. and Witt, S. F. (2015) ‘A

Meta-Analysis of International Tourism Demand

Elasticities’, Journal of travel research 54 (5) pp. 611–

633. doi.10.1177/0047287514528283.

Pham, T. D., Nghiem, S., and Dwyer, L. (2017) ‘The

determinants of Chinese visitors to Australia: A dynamic

demand analysis’, Tourism management (1982) 63268–

276.DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06 .015.

Prayag, G. and Ryan, C. (2011) ‘The relationship between

the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors of a tourist destination: the

role of nationality – an analytical-qualitative research

approach, Current Issues in Tourism, 14(2) pp. 121–143.

Pham, T. D., Nghiem, S., and Dwyer, L. (2017) ‘The

determinants of Chinese visitors to Australia: A dynamic

demand analysis’, Tourism management (1982) 63268–

276.DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017 .06.015.

Shu, M. H., Hung, W. J., Nguyen, T. L., Hsu, B. M., and

Lu, C. (2014) ‘Forecasting with Fourier residual

modified ARIMA model-An empirical case of inbound

tourism demand in New Zealand’, WSEAS

Transactions on Mathematics 13(1) pp. 12-21.

Song, H., Kim J. H. and Yang, S. (2010) ‘Confidence

intervals for tourism demand elasticity, Annals of

Tourism Research 37(2) pp. 377-396.

ICPDI 2022 - International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology

594

Schiff, A. and Becken, S. (2011) ‘Demand elasticity

estimates for New Zealand tourism’, Tourism

Management 32(3) pp. 564–575.

Tsui, W.H.K, Balli, F., Tan, D. T. W., Lau, O., and Hasan,

M. (2018) ‘New Zealand business tourism: Exploring

the impact of economic policy uncertainties’, Tourism

economics: the business and finance of tourism and

recreation 24 (4) pp. 386–417.

Tsui, W. H. K., Chow, C. K. W., Lin, Yi-Hsin, and Chen,

Po-Lu. (2021) ‘Econometric analysis of factors

influencing Chinese tourist visits to New Zealand’,

Tourism management perspectives 39(1) pp. 1-14

doi.10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100861.

Tribe, J. (2020) The economics of recreation, leisure, and

tourism. 6th and. Published by Routledge.

Tang, J. C., Chen, S. Q., (2017) ‘Estimating the elasticity

of China's inbound tourism demand based on an error

correction model’, Tourism Science 31(5) pp. 65-81.

doi.10.16323/j.cnki.like.2017.05.005.

Wu, N., Wang, Y.T., Tan, C.Y. and Zhou, G. (2020) A

study on the psychology and Service Demand of long-

haul Flight passengers. Available at:

https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?pap

erid=205e4e5bdd37ebc59317f67d335104ca

Analysis on the Determining Factors of International Tourism in New Zealand Optimisation of Computer-Based Algorithmic Linear

Regression Model

595