Institutional Economics in the Face of Global Challenges in Europe

Anna Dziurny

1 a

, Hanna B. Danylchuk

2 b

, Liubov O. Kibalnyk

2 c

, Liliya Stachowiak

3 d

and

Zenon Stachowiak

1 e

1

Cardinal Stefan Wyszy´nski University, 5 Dewajtis, Warsaw, Poland, 01-815

2

The Bohdan Khmelnytsky National University of Cherkasy, 81 Shevchenko Blvd., Cherkasy, 18031, Ukraine

3

Higher School of Management, 36 Kaw˛eczy´nska, Warsaw, Poland, 03-772

Keywords:

Globalization, Regionalization, Institutional Economics, Civilizational Challenges of the Modern World,

Major Development Problems of the Modern World (Demographic Situation of the World, State of the World’s

Natural Resources, Environmental Threats, World Food Situation, World Debt, Scientific and Technological

Progress).

Abstract:

The reflections undertaken, according to their authors, are an attempt to use the scientific achievements of the

new institutional economics to identify, analyze and evaluate global challenges for the European community.

They are an intellectual response to the development dilemmas of the contemporary world, which arouse the

interest of representatives of all contemporary currents of economic thought and practice. For the authors of

the article, the need and advisability of approximating and linking these two layers has also become an area of

research aimed at documenting the usefulness of an institutional approach to the study of complex problems of

the contemporary world – with emphasis on those concerning the European continent. With such expectations

in mind, the considerations were firstly focused on identifying the achievements of institutional economics as

an inspiration for solving the challenges of the contemporary world. In the second instance, the main focus is

on identifying, analyzing and assessing the challenges facing the European community in relation to human,

material and relational resources.

1 INTRODUCTION

The development challenges of the modern world

arouse the interest of many sciences – including all

contemporary currents of economic thought – and

prompt their representatives to address them. Their

persistence and even deepening proves the ineffec-

tiveness of generalizations of these problems by the

leading currents of classical economic thought. This

is the case when the practice of socio-economic life

forces the search for effective hints for their solu-

tion. This is the case when a set of challenge planes

is expanding, namely: political-military, social and

economic, natural-climate and ecological, technical-

technological, health, and cultural and civilizational

(Camdessus, 2019; Dziurny, 2020; Friedman, 2009;

Landes, 2015; Pobłocki, 2020; Randers et al., 2014;

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9190-8086

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9909-2165

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7659-5627

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0583-0874

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8842-7743

Stachowiak, 2004).

Many of the numerous development perturba-

tions of the modern world affecting changes in eco-

nomic activity and the well-being and prosperity of

the global community were recognized and identi-

fied in the Millennium Development Goals of the UN

Millennium Project - adopted at the UN Session in

2000 (O

´

srodek Informacji ONZ w Warszawie, 2022)

– and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

– adopted by the UN in 2015 (OECD, 2017). These

perturbations have also affected the European com-

munity, becoming the premise for the formulation of

challenges to be addressed as a responsibility of the

entire European community.

Their solution rests with a whole range of scien-

tific disciplines, which are expected to develop theo-

retical generalizations as well as practical directives

for their solution. One of these scientific disciplines

is institutional economics – which in its contempo-

rary perception is referred to as new institutional eco-

nomics. Its theoretical output, built on an interdis-

ciplinary approach to solving social and economic

102

Dziurny, A., Danylchuk, H., Kibalnyk, L., Stachowiak, L. and Stachowiak, Z.

Institutional Economics in the Face of Global Challenges in Europe.

DOI: 10.5220/0011931700003432

In Proceedings of 10th International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy (M3E2 2022), pages 102-121

ISBN: 978-989-758-640-8; ISSN: 2975-9234

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

problems, can become a source of inspiration for solv-

ing the challenges facing the European community

(Borkowska et al., 2019; Stanek, 2017; Stankiewicz,

2014).

2 INSTITUTIONAL ECONOMICS

AS AN INSPIRATION FOR

SOLVING THE CHALLENGES

OF THE MODERN WORLD

The logic of thinking reflected in the views of insti-

tutionalists, especially those representing the ‘new’

(as opposed to traditional) institutional economics, is

based on a paradigm referring to the scientific work

of leading neo-institutionalists. It refers to the tradi-

tional views of this current and the concepts used by

them, among which the category of “social institu-

tions” should be identified as the leading one under-

stood as dominant ways of thinking that take into ac-

count social conditions, the functions of the individ-

ual and the community, as well as habits of thought

and ways of apprehending phenomena by which peo-

ple are guided. Because they are products of the past,

adapted to new conditions, they are therefore never

in complete harmony with the requirements of the

present (T. B. Veblen

1

). The source of their transfor-

mation is to be found in the constant improvement of

technology (Veblen, 2008).

At the same time, institutionalists were aware – in

addition to the premises that determined the need to

articulate the paradigm of the new institutional eco-

nomics – of the demands placed on it, namely that: it

is not given once and for all – but should be adopted

by consensus of the majority of researchers. They as-

sumed that it could periodically undergo fundamen-

tal changes leading to profound changes in science

associated with the scientific revolution. They also

assumed that it should be characterized by: logical

and conceptual coherence; relative simplicity, i.e., it

should contain only those concepts and theories that

are genuinely necessary for the science in question;

and allow for the creation of detailed theories consis-

tent with known facts. This was followed by the for-

mulation of several fundamental questions, namely: is

reality objective or partly subjective? does one have

to be a participant in a social process in order to un-

derstand it well? and, does social reality undergo con-

stant change or is it still the same? The answers to all

1

Thorsten Bunde Veblen (1857-1929) – American of

Norwegian origin, sociologist and economist, master of the

entire institutional stream. Author of “The Theory of the

Leisure Class” (1899).

of these questions provide a substrate for the identi-

fication and solution of Europe’s global and regional

development problems.

Useful for addressing the challenges of the mod-

ern world – according to the authors of the article – is

the fact that the institutionalists enriched the picture of

the process of socio-economic development with the

setting of ‘culture’, which they saw as an organized

system of human behavior in which there is an insti-

tutional (also called ceremonial) area on the one hand

and a technological area on the other (Stankiewicz,

2014). In their view, any economic system remains

under constant pressure, on the one hand from the

forces of various institutions (legends, customs, social

hierarchies) and on the other hand from the incentives

generated by technology (C. E. Ayres

2

).

Institutionalists, referring to the instrumental phi-

losophy dealing with the use of limited resources

to achieve individual and group goals, formulate the

postulate of adaptation of these opposing forces. The

area of this process is the economic system, which is

formed by two interrelated but contradictory blocks:

the first is the block of the price economy identified as

a complex of historically shaped institutions adopting

ceremonial behavior, whose value derives from power

based on the power of money; the second is the block

of the industrial economy based on technology, sci-

ence and the proliferation of labor tools. Each gen-

erates different values, the first price value and the

second industrial value. Their synthesis is the idea

of a rational society, whose determinants should be

abundance of goods, quality of life, freedom, security

and excellence. The progress of society, understood

in this way, should be aimed at, that is, the progress

that ensures the continuity of humanity through the

development of science and creativity, rather than the

progress that pursues the goals of maximizing utility

and satisfaction resulting from the aspirations of indi-

viduals. The correct direction of its evolution should

be supervised by the institution of social planning.

Views formulated on the basis of an analysis of

the disintegration of 19th century civilization char-

acterized by: balance of power, gold standard, self-

regulating market and liberal state (K. Polanyi

3

), sup-

ported by arguments from economic anthropology,

2

Clarence Edwin Ayres (1891-1972) – American, pro-

fessor of economics and philosophy, representative of one

of the most important centers of evolutionary economics

(University of Texas at Austin). Author of many publi-

cations, including: “The Theory of Economic Progress”

(1944) and “Toward a Reasonable Society” (1962).

3

Karl Polanyi (1886-1964) – Austrian, lecturer at the

universities of Oxford and London. The author of the work

“The Great Transformation; The Political and Economic

Origins of Our Time” (1944).

Institutional Economics in the Face of Global Challenges in Europe

103

should be considered useful and valuable, for the in-

vestigations undertaken. They proved that this civi-

lization collapsed because its economy was based on

self-interest and worked against the interests of soci-

ety (Stankiewicz, 2014).

Necessary for deliberations aimed at identifying

the challenges facing Europe and developing direc-

tives for solving them is to take into account the

methodological achievements of the representatives

of this current (I. Lakatos

4

), who, despite their often-

diametrical differences (K. R. Poper

5

, T. S. Kuhn

6

),

tried to bridge the gap between them. On the one

hand, the research procedure leading to a theory from

making a lot of observations and using inductive rea-

soning (K. R. Poper) was rejected, postulating a re-

search path according to the scheme: posing a certain

problem by the existing theory – eliminating the er-

rors of the old theory – posing a new problem. In this

connection, historicism was also fought against as a

view of being able to predict the inevitable course

of history. On the other hand, historical knowledge

was assigned an important role (T. S. Kuhn), believing

that it should not be regarded merely as a repository

of chronological descriptions of events, which seek

to reconstruct a continuous line of development, but

as a detection of the integrity of science in particular

periods. This was followed by the introduction as a

particular “matrix of scientific discipline”, which was

understood as a set of certain generalizations, models,

values and patterns accepted by scientists. Within it is

placed the practice of ‘normal’ science, whose task is

to solve various ‘puzzles and riddles’ until anomalies

emerge, that is, facts that cannot be explained on the

basis of the matrix. These views have tried to recon-

cile (I. Lakatos) by seeking a certain synthesis of their

approaches, while proclaiming their own reflections

(Stankiewicz, 2007).

With regard to economics, the concepts of sci-

entific research programmers are pointed out, in the

structure of which it is necessary to distinguish be-

tween a “hardcore” forming a set of fundamental and

conditionally unquestionable assumptions, the con-

tent of which is subject to slow changes; and a “pro-

4

Imre Lakatos (1922-1974) – Hungarian of Jewish de-

scent. Methodologist. Author of the works: “Essays In

the Logic of Mathematical Discovery” (1961), “Criticism

and the methodology of scientific research Programmes”

(1968).

5

Karl Rajmund Popper (1902-1994) – Austrian physicist

and logician. Author of the works: “Logik der Forschung”

(1935); “The Poverty of Historicism” (1957) and “Objek-

tive Knowledge ”(1972)

6

Thomas Samuel Kuhn (1922-1996) – American histo-

rian and philosopher of science. The author of the work

“The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” (1962)

tective belt”, which surrounds the “hardcore” and

which consists of auxiliary hypotheses, modified ac-

cording to the needs of defending the foundations

of the scientific research program and whose content

must be frequent.

The resultant of all the views cited allows the

idea of the paradigm of the new neo-institutional eco-

nomics to be outlined. It refers to a holistic cogni-

tive approach imposing the need to use a modeling

method (more specifically, a benchmark model) al-

lowing to focus attention on the relations between the

parts and the whole, to search for a coherent unity of

phenomena and to follow the process of social evolu-

tion. It is based on a set of elements that constitute the

‘core’ of the paradigm and the ‘safety belts’ that con-

stitute its environment. This implies the need to make

interdisciplinary use of the contributions and achieve-

ments of other scientific disciplines, especially tech-

nology, law, sociology, social psychology, pedagogy,

or even neurology, anthropology and other sciences

(Stankiewicz, 2007).

At the core of the New Institutional Eco-

nomics paradigm are four structural elements: “so-

cial ceremonies” and “technology” (corresponding to

T. B. Veblen’s ideas of the business world and the in-

dustrial world); “philosophy” (referring to the views

of C. E. Ayres, J. Dewey’s

7

pragmatism and instru-

mentalism) and “environment” (based on the views of

K. Polanyi and his economic anthropology). Each of

these elements has its own “safety belt” which is its

environment and characterizes its essential determi-

nants. “Social ceremonies” are described by the deter-

minants: institutions, beliefs and values. “Technolo-

gies”, in turn, are described by the determinants: tools

and qualifications. “Environment”, on the other hand,

is concretized by the determinants: flora, soil, fauna,

climate. “Philosophy”, on the other hand, is described

by the determinants of social legitimacy (referring to

the criteria of social legitimacy – “social legitimacy”

by W. C. Neale

8

); participatory democracy (based on

the essence of participatory democracy – “participa-

tory democracy” by M. T. Tool

9

) and sufficiency (re-

ferring to “sufficiency” by K. Polanyi).

7

John Dewey (1859-1952) – American, supporter of in-

strumentalism (varieties of pragmatism). He brought his

ideas to institutionalism.

8

Walter Castle Neale (1925-2004) – author of theorems

on the criteria of social legitimacy.

9

Marc R. Tool (1921-2018) - creator of the concept of

participatory democracy. Author of “The Discretionary

Economy: A Normative Theory of Political Economy”

(1979), and “Essays in Social Value Theory: A Neoin-

stitutionalist Contribution” (1986). He was the editor of

“An Institutionalist Guide to Economics and Public Policy”

(1984).

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

104

The formula of the presented paradigm of institu-

tional economics assumes that the observer of real-

ity who intends to study it cannot be neutral and will

not be objective, because he is always a representa-

tive of a particular culture. In doing so, he or she

must take into account the achievements of many sci-

ences in order to make value judgments. With this

in mind, attempts are being made to refine it (F. G.

Hayden

10

, G. M. Hodgson

11

). In the first instance,

the concept of a matrix array of the social system is

promoted, composed of streams and resources with

no single denominator, whose individual cells inte-

grate relations of free benefit, distribution and ex-

change (F. G. Hayden). Four issues are also intro-

duced into the paradigm of institutional economics:

the concept of exchange understood as the transfer of

property rights; the institutions of the market seen as a

set of social institutions in which goods are exchanged

with particular regularity; the enterprise as a creature

that ensures the reduction of opportunity costs, oper-

ating under conditions of uncertainty and practicing

economic calculation; expectations that boil down to

the demand for the creation of institutions conducive

to the formation of a mixed socio-economic arrange-

ment in the future, in which tradition, market and

planning will coexist (G. M. Hodgson).

An important aspect of neo-institutionalist

views is their orientation towards cultural premises

(S. Huntington

12

), which, alongside ideological and

economic premises, can be the generator of many

threats. The multidimensionality of culture, in their

view, increasingly causes the differentiation of the

world, strongly influencing ideology and economics,

succumbing also through feedback to their influence.

However, it should also be borne in mind that, despite

10

F. Gregory Hayden – American, professor at the Uni-

versity of Nebraska. The author of the concept of the social

system matrix, composed of flows and resources, without

a uniform denominator. The individual cells of the matrix

integrate the relationships of free benefits, distribution and

exchange. He treated the matrix table as a helpful tool for

analysts and planners.

11

Geoffrey M. Hodgson (1946-) – Englishman, lecturer

in economics at British, French, Austrian, Swedish, Amer-

ican and Japanese universities. Author of works: “Eco-

nomics and Institution. A Manifesto for a Modern In-

stitutional Economics” (1989); “Economics and evolution:

bringing Life back into Economics” (1993); “Evolution and

Institutions. On Evolutionary Economics and the evolution

of Economics” (1999); “The Evolution of Institutional Eco-

nomics: Agency, Structure and Darwinism in American In-

stitutionalism” (2004).

12

Samuel Phillips Huntington (1927-2008) – American

political scientist, author of publications “The Clash of Civ-

ilizations?” (1993), “The Clash of Civilizations and the Re-

making of World Order” (1996).

the growing importance of cultural premises, there is

– as they point out – a persistence of national cultural

economics on the basis of psycho-physical and

organizational characteristics (Huntington, 2001).

The output of the institutional economics stream

was considered to be usable for a new view of eco-

nomic theory. The considerations undertaken in its

field should be focused both on the theory of the func-

tioning of the mechanisms of social economics, in-

cluding: the controversies and dilemmas around its

fundamental problems; and the institutional view of

their resolution. Such a logic of approach to eco-

nomics should be subordinated to addressing, inter

alia, such problems as: the theory of design of socio-

economic mechanisms, namely: the concept of mo-

tive congruence (L. Hurowicz

13

) – that is, the desired

state of behavior of participants in a social mech-

anism; the principle of disclosure (R. Myerson

14

)

treated as a technical concept, allowing the construc-

tion of general theorems on the feasibility of using

resource allocation under conditions of incentive con-

straints and economic problems burdened by adverse

selection and moral hazard; and implementation the-

ory (E. Maskin

15

) emphasizing the completeness of

the elements of a theory to ensure its effective coher-

ence. Opportunities are also indicated to invoke the

achievements of public choice theory and political cy-

cle theory, attempting to explain changes in the struc-

ture of institutions under the influence of competition

between individuals and organizations in the political

market.

Recalling the indicated determinants of the institu-

tional outlook on the challenges to civilization emerg-

ing before European society, the logic of their identi-

fication, analysis and characterization can be put into

a set of overlapping global development problems of

Europe within the idea defined by the framework of

13

Leonid Hurowicz (1917-2008) – Polish-American

economist of Jewish origin. Nobel Prize winner. Au-

thor of the theory of designing mechanisms presented in

the works: “The Theory of Economics Behavior” (1945);

“On the Concept and Possibility of Informational Decen-

tralization” (1969); “The Design of Mechanisms for Re-

source Allocation” (1973); “Designing Economic Mecha-

nism” (2006).

14

Roger B. Myerson (1951-) – American professor of

economics. Nobel Prize winner. It is one of the world’s

leaders in mathematical economics, econometrics, mathe-

matical economics and game theory. Author: “Game The-

ory: Analysis of Conflict” (1991), “Probabilistic Models for

Economic Decisions” (2005).

15

Eric S. Maskin (1950-) – British professor of eco-

nomics. Nobel Prize winner. Author of fragments of works:

“Economic Analysis of Markets and Games” (1992); “Re-

cent Developments in Game Theory” (1999); “Planning,

Shortage, and Transformation” (2000).

Institutional Economics in the Face of Global Challenges in Europe

105

the paradigm of new institutional economics. In the

first place, they are formed by a core reflecting a set of

population resource factors, a set of capital resources

(material, financial) and a set of relations. The first set

includes demographic issues, population allocation

and migration, labor resource activity, and poverty

and malnutrition. Second, on the other hand, material

issues viewed through the prism of availability of raw

materials, industrial and agricultural production and

the conditions of its implementation and effects. In

turn, the third from a set of socio-cultural, scientific-

technical and balance sheet relationships (Dziurny,

2020; Rosling et al., 2018; Schwab, 2018).

3 GLOBAL CHALLENGES FOR

EUROPE

Focusing only on those challenges that relate to so-

cial and economic issues, it should be noted that

they have been addressed for more than half a cen-

tury by scholars, practitioners and politicians repre-

senting many of the world’s leading opinion form-

ers, such as the Club of Rome, the Rand Corporation

or the National Intelligence Council. Virtually every

country has established centers dealing with the is-

sue of civilizational challenges. In Poland this is the

Forecasting Committee “Poland 2000” at the Presid-

ium of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Opinions of

all these institutions have shown that the contempo-

rary world, at the stage of transition from the indus-

trial to the information and information age, reveals

clearly visible global development megatrends, which

outline the civilizational trends occurring in the con-

temporary world economy, characterized by relative

permanence, anticipation and universalism, towards

which an economic society cannot remain indifferent.

Their list must include phenomena relating to popu-

lation (demographic, migration, health, poverty, ...),

social reproduction (raw material, material, capital,

economic relations...) and civilization (scientific and

technological progress, cultural progress, ...) (Dzi-

urny, 2020).

The problems indicated, each of which generates

development challenges on the one hand and devel-

opment threats on the other hand, also concern Eu-

rope (Krzynówek et al., 2009;

˙

Zukrowska, 2015). The

continent, which currently numbers 46 internationally

recognized countries, 4 countries with limited inter-

national recognition and 7 dependent territories, is not

homogeneous according to the commonly accepted

criteria of their characterization and assessment. The

vast majority of them are in the group of more de-

veloped countries (high, medium), but some are also

in the group of less developed countries. In the land

area of the world, which is about 130.1 million km

2

(of which only about 30% is inhabited), the European

continent covers over 22.1 million km

2

, which places

it on the third position in the world (Roc, 2021).

3.1 Challenges to Population Resources

The great challenge facing the European community

is to address the population problem at all levels of

its manifestation, that is, demographic, allocation and

migration, the productive capacity of labor resources,

and the vices of life such as poverty and malnutrition.

On most of them, it has more positive overtones than

in the world as a whole and in the group of less devel-

oped countries (table 1).

Primary among the population challenges for Eu-

ropean communities is adapting to the consequences

of demographic change on the continent and globally

(table 1). At present (beginning of 2022), there are

almost 8 billion people in the world, more than 780

million of whom live in Europe, i.e., 9.6% of the total,

compared to 59.5% in Asia, 17.2% in Africa, 8.3% in

Central and South America, 4.7% in North America,

0.6% in Australia and Oceania. The achievement of

such a large human population, despite frequent crop

failures, devastating wars and major epidemics of in-

fectious diseases, was largely the result of civiliza-

tional advances in medicine favoring the control of

many infectious diseases, improved life hygiene and,

consequently, a reduction in infant and child mortal-

ity and an extension of human life. On the other hand,

the uneven distribution of the world’s population, in

relation to the level of development achieved in the

various regions of the world, makes it necessary for

Europe to counter the excessive influx of emigrants

(Dziurny, 2020).

An analysis of demographic change in the 21st

century shows significant population growth both

globally and on individual continents (table 1). Pro-

jections (according to the UN medium projection

variant) assume that population growth will occur at

a rate of around 0.5 billion per decade. It is estimated

that the population will be over 8.5 billion in 2030 and

around 9.8 billion in 2050, rising to around 11 bil-

lion in 2100. This situation will occur despite the fact

that the growth rate of the world’s population over-

all is declining, while it is increasing significantly in

the regions least able to provide health, food, stabil-

ity, work and prosperity to an increasing number of

people (Simon et al., 2010; Roc, 2021).

The greatest population growth is and will con-

tinue to be in the developing world, which will exac-

erbate many of these countries’ development issues,

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

106

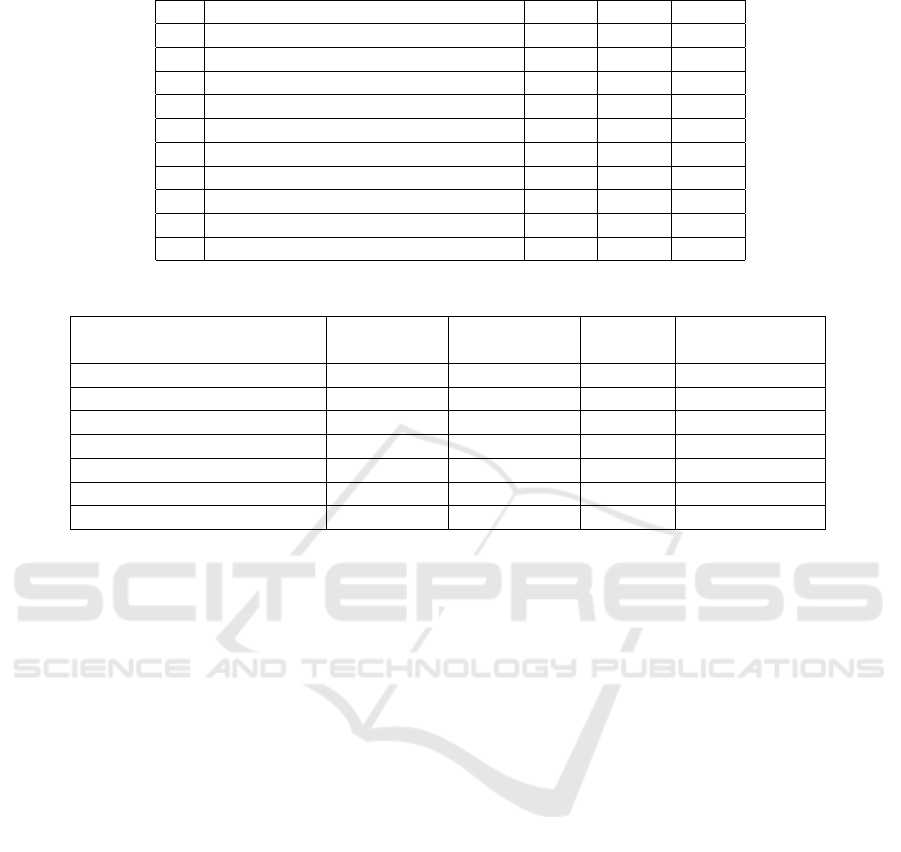

Table 1: Characteristics of the European population in relation to world regions (Roc, 2021).

Description 2000 2010 2020

Population in millions

WORLD 6127 6958 7795

More developed regions 1171 1235 1286

Less developed regions 4956 5723 6509

Europe 726 737 748

Percentage of working people at risk of poverty by international poverty line (in %)

WORLD 18.9

1

14.0 6.6

Sub-Saharan Africa 50.5

1

45.5 36.7

South Asia 31.3

1

22.6 8.7

Europe 0.1

1

0.0 0.0

Prevalence of malnutrition (in %)

WORLD 12.4

1

9.2 9.9

Sub-Saharan Africa 24.6

1

19.4 24.1

South Asia 20.5

1

15.6 15.8

Europe <2.5

1

<2.5 <2.5

Percentage of people using drinking water distribution (in %)

WORLD 66

1

71 74

Sub-Saharan Africa 20

1

22 30

South-east Asia 52

1

54 57

Europe 90

1

91 94

Notes: 1 – year 2005

especially in the areas of education, housing, food and

water supply and employment. If at present, i.e., at

the beginning of the third decade of the 21st century,

the birth rate is 10.9 persons per 1 000 population in

the world (0.6 persons in more developed regions and

12.9 persons in less developed regions) and -0.7 per-

sons in Europe, then in the middle of the 21st century,

it is projected at 5.6 persons in the world (-1.8 per-

sons in more developed regions and 6.7 persons in

less developed regions) and -2.3 persons in Europe.

The emergence of this situation is influenced by the

level of socio-economic and cultural development of

society, which is conducive to a successive increase

in living standards. It has also become apparent that

a very low human birth rate is taking place - and will

continue to do so - primarily among people belonging

to the Western cultural sphere, who now account for

around 13% of the world’s population (Camdessus,

2019; Roc, 2021).

In countries with established consumer lifestyles,

high automation of production, high levels of educa-

tion and qualification of people, and satisfactory fi-

nancial opportunities, two negative correlations can

be seen. The first – the higher the standard of living,

the lower the birth rate and the second – the lower the

level of economic development, the higher the death

rate. These trends lead to an increase in people’s life

expectancy, albeit on a markedly different scale. Life

expectancy is projected to reach 77 years by the mid-

dle of the 21st century, with almost 84 years in more

developed areas and almost 76 years in less developed

areas (Roc, 2021).

Projections for Europe assume an average life ex-

pectancy of almost 83 years in this period. This means

the consolidation of the trend of aging of the Euro-

pean population, which is the result not only of low

birth rates, but also, in some countries of the conti-

nent – formerly belonging to the group of planned

economy countries – changes in the structure of the

economy, lack of life stability (no jobs, no housing,

low wages). Now, it is at the beginning of the third

decade of the 21st century, due to the effects of the

COVID-19 pandemic, that a trend is beginning to

emerge, reflected in a noticeable reduction in life ex-

pectancy in many countries (Gorynia and Mroczek-

D ˛abrowska, 2021).

The population issue must also be viewed from

the point of view of its impact on the size and struc-

ture of the labor force (workforce), its age and la-

bor force participation and allocation. Countries with

a large post-working-age population and a relatively

small working-age population, as well as a small per-

centage of women and children, reveal aging ten-

dencies. Hence, this group of countries – which

also includes European countries – reveals a grow-

ing demand for labor generating, at the same time,

Institutional Economics in the Face of Global Challenges in Europe

107

large-scale migration processes from less developed

areas with larger working-age populations in under-

and medium developed countries constitutes the main

source of cheap labor for developed countries.

This direction of perceptions and evaluations of

this phenomenon is confirmed by analyses of the

state and projections of the demographic burden, i.e.,

the scale of the percentage ratio of the number of

non-productive (pre-productive and post-productive)

to productive people. Considered at the level of labor

force reproduction, they indicate that the population is

a function of natural increase, i.e. the difference be-

tween the number of births and the number of deaths.

It is influenced by many economic, social and cultural

factors. The birth rate is mainly determined by the

fertility rate and the length of a woman’s childbearing

years. Models of demographic change assume a 15-

or 25-year reproductive period. A 15-year reproduc-

tive period with an assumed 3.5-year birth interval re-

sults in a fertility rate of 4.3 children, while a 25-year

reproductive period with an assumed 1.5-year birth

interval results in a fertility rate of 16.7 children. In

practice, the highest fertility rates are eleven / twelve

children. Another important factor is the increasing

lifespan of people. The existing state and forecasts

of this phenomenon signal a growing threat expressed

in the necessity of securing the material basis of ex-

istence by a decreasing population of productive peo-

ple with a growing population of non-productive age

(Roc, 2021).

Analysis of old-age dependency estimates and

projections shows that since the third decade of the

21st century, the number of people of working age is

decreasing relative to the number of people of non-

working age. This situation is taking place both in

the group of more and less developed countries, with

quite significant differences in the total and in individ-

ual groups. In the group of more developed countries,

these proportions are the worst at present – accord-

ing to data for 2020, there are 45.7% and 46.4% of

the total working age population in Europe, with pro-

jections of this figure for the middle of the 21st cen-

tury at 25.4% in Europe and 36.2% in North America.

This situation is primarily a consequence of increas-

ing life expectancy, far less a consequence of popu-

lation growth expanding the stock of people of pre-

working age (Roc, 2021).

At the end of 2020, the world’s labor force (em-

ployed and unemployed) amounted to almost 3.5 bil-

lion people, with significant differences in territorial

allocation. Asia (excluding Central Asian and Arab

countries) and the Pacific had the largest share with

57.1%, followed by Africa with 14.3%, Europe and

Central Asia with 12.8%, Central and South America

with 8.6%, North America with 5.5% and Arab coun-

tries with 1.7% of the total labor force (Roc, 2021).

The existing population situation, also contributes

significantly to increasing migration phenomena –

both internal and external. On a global scale, exter-

nal migrations taking various forms of exile, above

all economic, political, military, cultural, ethnic and

religious, are particularly dangerous. Increasing dif-

ferences in demographic structure between devel-

oped countries, progressing globalization processes

and political and military tensions between the world

and developing countries contribute to their widen-

ing scale. They are also reinforced by civilizational

advances in digital communication and mobility and

the rise of nationalist attitudes in many regions of the

world.

External migration processes give rise to numer-

ous direct and indirect threats and are a breeding

ground for many social tensions and conflicts. Di-

rect threats include problems such as food, employ-

ment and unemployment, environmental devastation

and urbanization. Indirect effects, on the other hand,

are mainly: the severance of traditional social ties;

changes in the system of social norms and the value

system; a reduction in internal security; and an in-

crease in violence and crime.

The scale of the external migration problem is sig-

nificant. According to UN data, in 2020 the number

of migrants in the world will be over 270 million peo-

ple (almost 3.5 percent of the total world population),

which compares to 2000 (150 million people) and

2010 (214 million people) a marked increase (Wor,

2022).

An increasing proportion of the migrant popula-

tion are refugees, i.e., people who have been forced

to leave their home country because of wars and per-

secution. Estimates, according to the United Nations

High Commissioner for Refugees, place their size at

the beginning of the third decade of the 21st cen-

tury at around 85.5 million people, including 25.6

million men, 22.3 million women and 34.6 million

children and young people. Currently (at the end of

May 2022), the number of refugees has exceeded 100

million people. A significant proportion of them are

choosing Europe as their destination. The scale of the

problem on the European continent is currently being

expanded by the refugee situation from Ukraine. Ac-

cording to information from the country’s border ser-

vices, more than 6 million people have left the country

(as of the end of May 2022) – of whom more than 4.3

million have entered Poland. In addition to this, the

consequence of Russia’s barbaric assault on Ukraine

has resulted in a large internal refugee population es-

timated at over 6 million people (Wor, 2022).

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

108

A certain novelty in the shaping of the external

migration flow is the so-called “climatic migration”,

which is increasing year by year, contributing to an

increase in the number of emigrants, for climatic and

natural reasons.

Migration patterns outlined in the first decades of

the 21st century indicate that the largest population

movements have occurred within individual regions

of the world, rather than between continents. Inter-

nal continental migration in Europe now significantly

exceeds the influx of Africans and Asians to the old

continent. It is generally characterized by a direction

from economically backward countries and countries

experiencing development difficulties to more devel-

oped countries. This means that the West is facing

increased migration and refugee flows from poor or

conflict-prone regions of the world. In addition to this

trend, some changes in migration routes can be ob-

served. One of the leading ones is the route of the

influx of migrants to France, Germany and the UK

(Sachs, 2009).

A major population problem at the turn of the 20th

and 21st centuries is meeting health and epidemic

challenges – both globally and in Europe. These

problems have accompanied man since the begin-

ning of his existence on earth. Infectious diseases

have proved to be the most important threat to hu-

man health, resulting in enormous human morbidity

and mortality. They have not lost their relevance even

today, just in the decades of the late 20th and early

21st century. If, worldwide, there were 1043 events

resulting in 19.3 million infected people, including

162 000 deaths, in Europe there were only 104 events

resulting in 189 000 infected people, including only

4 000 deaths. By far the greater health devastation

worldwide as well as on the European continent was

caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus pathogen identified

in November 2019 as an epidemic, since March 2020

it has been referred to as pandemic COVID-19. It

has contributed to the illness of more than 368 mil-

lion people and the death of more than 5.6 million

people by the end of January 2022. Europe proved to

be the area of dominant outbreaks after the American

continent. Out of 121.7 million infected, more than

1 609 000 people died. Community To the greatest

extent, according to the number of deaths, this sit-

uation affected the communities of Russia, the UK,

Italy, France, Germany, Poland and Spain. It has

caused global social, political and economic disrup-

tion (Wor, 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed a wide range

of areas of potential risk. It has contributed not only to

high morbidity and mortality but also to the existence

of many negative economic impacts across sectors, all

entities and all forms of human activity. It has neces-

sitated many new phenomena, such as remote work-

ing, mandatory quarantines shortages of emergency

medical, health and safety equipment for citizens. In

the economic sphere, it has caused a global weaken-

ing of economic activity. Supply shortages, largely

caused by panic buying, became apparent. There have

been numerous disruptions in the supply chains of

consumer and investment goods. In succor of this

situation comes the concept of sharing resources and

services. In the social and living sphere, society has

revealed negligence in the provision of clean air in

dwellings, as well as overcrowding. The availabil-

ity of measures to improve this situation has become

an important issue. Numerous controversies were re-

vealed by the pandemic in the social sphere. Accord-

ing to a section of the world community, the pandemic

is being used to impose a unified vision of the world

and subject people to total control. These opinions

correspond to the facts in many countries of the mod-

ern world, where the freedom of their citizens has

been drastically curtailed. Fear of a pandemic has

set in motion processes of sanitization (segregation,

selection) and the practical abolition of fundamental

human rights and the imposition of total surveillance.

This is accompanied by the emergence of disinforma-

tion and conspiracy situations, giving rise to attitudes

of xenophobia and racism. They have also contributed

to the emergence of many anti-vaccine attitudes.

The consequence of the current and future health

and epidemic situation of the world is the accumu-

lation of numerous developmental barriers and risks.

These are psychological-biological, psychosocial, as

well as civilizational (technical, technological) and

spatial in nature. Their limitation and overcom-

ing forces the world community to creatively oppose

these phenomena in all areas of human life. Health

care and the pharmaceutical market were affected

first; the labor market and education followed (Solarz

and Waliszewski, 2020).

The pandemic also revealed many new areas of so-

cial activism. The response to the barriers and threats

in these areas has been the search for solutions to

the challenges they bring. Its practical implementa-

tion has been facilitated by the development of digi-

tal economy technologies. The exchange of resources

has taken on a completely different dimension by em-

bracing further sectors of the economy. The idea of

economic rationality, both in terms of consumption

and investment, has also returned.

An important problem of the contemporary

world – including Europe – that is directly related to

the population problem is the issue of poverty and de-

privation. They are a consequence of development

Institutional Economics in the Face of Global Challenges in Europe

109

inequalities, translated into differential labor income

and inequalities of ownership of capital and property.

They manifest themselves not only at the regional and

national levels, but also at the individual level. For

Europe, it is important to consider this issue first and

foremost at the individual level, as it leads to the gen-

eration of hunger and malnutrition (Landes, 2015).

Poverty is now defined as a systemic risk, deter-

mining the poverty level of all those whose income

barely exceeds the extreme poverty threshold and who

consequently form the poor layer. For them, the need

for social inclusion and the improvement of their liv-

ing conditions and cultural diversity is recognized. In

this process, appeals to the principles of: respect for

the dignity of every human being; equality and jus-

tice; respect for all human rights and the letter of the

law; and ensuring the sustainability of the democratic

system.

Poverty, as already pointed out, is always linked

to malnutrition (hunger) and also to development

(growth). These links and relations reveal both the

traditional approach (poverty – unsatisfied material

needs; hunger – insufficient food for all; develop-

ment – linear from tradition to modernity) and the

alternative approach (poverty – unsatisfied material

and immaterial needs; hunger – sufficient food, with

a poor system of distribution and right to food; de-

velopment – differentiated). Its externalization on a

global scale is the determinant of the level of GDP per

capita per day, referred to as the international poverty

line. According to the World Bank’s methodology,

a daily expenditure level of less than USD 1.90 per

capita (at purchasing power parity in 2011 prices) is

considered poverty (Roc, 2021). In Europe, on the

other hand, poverty is defined, following the defini-

tion in force since 1984, as a situation that refers to

individuals, families or groups of people whose re-

sources (material, cultural and social) are limited to

such an extent that it excludes them from a minimum

way of life in the country in which they live. Follow-

ing this approach, Eurostat has generated an indica-

tor of poverty and deprivation in Europe, correspond-

ing to nine points, namely: inability to incur unex-

pected expenses; inability to go on a week’s holiday

away from home; having arrears (e.g. mortgage, non-

payment of rent, etc.); inability to buy every second

home; and inability to live in a country where they

live; inability to buy a meal every other day that in-

cludes meat, chicken, fish or a vegetarian equivalent;

inability to heat the home adequately; not having a

washing machine; not having a color television; not

having a telephone; not having a personal car (Dzi-

urny, 2020).

A significant proportion of the global community

is affected by poverty, even though the number of peo-

ple living in poverty decreased by about 200 million

during the first decades of the 21st century, while the

world population grew by about 1.5 billion people.

According to the World Bank, in 2018 poverty lev-

els have fallen to 8.6 percent and are estimated to

continue to decline. Currently, the phenomenon of

poverty affects a large swathe of the population as at

least 750 million people were living on less than USD

1.9 a day (Wor, 2022).

An analysis of the level of poverty – measured

by the percentage of people at risk of poverty – on

a world scale, in the first two decades of the 21st cen-

tury, shows (table 1) a significant reduction.

The poorest region in the world remains sub-

Saharan Africa and South Asia. In 2020, these two

areas accounted for about 85% of global poverty, with

sub-Saharan Africa accounting for 36.7% (over 420

million people) and South Asia 8.7% (about 200 mil-

lion people). In the rest of the world, the percent-

age of poverty does not exceed 5%. The situation is

best in North America and Europe (Roc, 2021). The

prospect of eradicating poverty – according to the in-

stitutions responsible for this task – by 2030 does not

seem realistic. This is because it involves providing

the poor with humanitarian aid as well as investment

aid, especially in building human capital and promot-

ing growth that takes into account the interests of the

poor.

Population issues, largely as an aftermath of

poverty and deprivation, also involve feeding the

global community (Caparrós, 2016). Due to a mis-

match between food production and its desired con-

sumption, a significant proportion of the world’s pop-

ulation is undernourished or starving. Although these

phenomena manifest themselves in the practice of

most countries of the world, they are concentrated

only in certain regions of the world. The level of mal-

nutrition, as defined by the prevalence rate of mal-

nutrition expressed in %, although clearly decreasing

globally (table 1), remains high in sub-Saharan Africa

and South Asia. The best situation is in North Amer-

ica and Europe where it has remained below 2.5% for

years.

According to the FAO, the World Food and Agri-

culture Organization, there are currently more than

1 billion hungry people in the world. In turn, es-

timates by the UN Food and Agriculture Organiza-

tion cite a figure of 2 billion (about 30% of the total)

of the world’s population who are undernourished –

of whom more than 830 million people are starving,

of whom more than 650 million suffer from extreme

hunger – 150 million of them children. It is esti-

mated that the level of 400 million undernourished

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

110

will not be reached until 2050. Sub-Saharan Africans

account for the largest proportion of the undernour-

ished. Hunger and malnutrition are characteristic of

less developed countries, but it also affects communi-

ties in developed countries. Estimates suggest that 16-

20 million people are affected in this group of coun-

tries. These include some countries in the West, as

well as in the East, especially those that are trans-

forming their economies (Stowarzyszenie Demagog,

2022).

Following the division made, it should be noted

that the problem of malnutrition mainly affects un-

derdeveloped countries, where the main cause of food

shortages in these countries is the rapid growth of the

population, disproportionate to the possibilities of in-

creasing agricultural production (Stachowiak and Sta-

chowiak, 2022).

The consequences of hunger are numerous dis-

eases, often leading to death. The FAO estimates that

around 30 million people die every year from hunger

and malnutrition. In practice, this means that some-

one dies of hunger every four seconds in the world.

This situation occurs not so much because there is a

physical shortage of food, but because poor countries

do not have the financial resources to purchase it from

countries with large stocks of agricultural commodi-

ties. For a large part of the world’s population, hunger

and malnutrition are no longer present in their lives,

but for the rest it is still present. Today, hunger is still

a daily reality and has many dimensions.

Given the large increase in population and per

capita income, the world’s ecosystem is threatened

by human activities, including those related to food

production, processing and storage. Its consequence

can be the phenomenon of the scarcity of healthy and

potable water. At the beginning of the 21st century,

some 1.1 billion people did not have access to it –

mainly in Africa and Asia. This situation is linked

to a decline in groundwater levels, which has be-

come apparent in large areas of China, western Asia,

the Middle East, the former USSR and the western

United States. More than half of the world’s rivers

are over-exploited and significantly polluted. A large

proportion of the world’s population (around 2.6 mil-

lion people) lives without sanitation. Analyses of the

availability of safely managed water distribution point

to this issue. These are characterized by far-reaching

variations across the globe. If this does not pose

a significant problem in North American and Euro-

pean countries, one does with regard to sub-Saharan

African countries. The solution to this problem in-

volves the need for official development assistance

(table 1). If the situation does not change in future

decades, the problem of water scarcity is likely to af-

fect hundreds of millions of people. Due to climate

change, it will be impossible to cultivate land in many

areas of the world.

Reduced availability of water, generates another

significant threat to the world which is soil erosion,

amplified by the impact of inappropriate farming

methods, inadequate irrigation and increased salin-

ity of the land. Manifestations of these threats are

increasing natural disasters on a global scale, caus-

ing significant material, financial and human damage

(Stachowiak, 2004).

3.2 The Challenges of Civilization to

Material Resources

The first of the problems to be addressed as a lead-

ing solution is the issue of the progressive processes

of diminishing and even depleting natural resources

worldwide. These have a significant impact on Eu-

rope’s economic development, raising the question of

how to obtain them, both physically and economi-

cally. Their characteristic feature is that they are lim-

ited and unevenly distributed. They are available from

only three zones of the Earth: the hydrosphere, the

atmosphere and, for the most part, the Earth’s crust.

They are renewable and non-renewable in nature. By

2030, cumulative resource consumption is not yet

expected to significantly compromise economic de-

velopment opportunities. While it is estimated that

there are still opportunities to reproduce renewable

resources through reproduction, assessments as to the

sufficiency of mineral resources vary widely and do

not present a clear-cut vision. They give both pes-

simistic and optimistic assessments. The former point

to their deepening scarcity, due to ongoing popula-

tion growth and economic development. The domi-

nant optimistic assessments, however, point to the po-

tential for expanding resource substitution and new

technologies, saving known and currently used raw

materials and creating new types of materials.

The Earth’s raw material resources, in addition to

being limited, are characterized by their uneven use.

Only 20% of the world’s wealthier people use 85%

of the world’s timber, 75% of its metals and 70% of

the world’s energy production. According to UN data,

around 80% of the world’s wealth is held by 15% of

the population. It is also legitimate to conclude that

the size of the world’s resources is limited, although

still not fully known, which should be seen as a warn-

ing. This situation is particularly noticeable with re-

gard to fossil energy resources. The structure of their

recognized resources, estimated at 1057 billion tons

of conventional fuel, is dominated by coal (around

63%), followed by liquid fuels (around 19%) and gas

Institutional Economics in the Face of Global Challenges in Europe

111

(around 17.7%) (Sachs, 2009).

At the beginning of the third decade of the 21st

century (2022), the recognized reserves of hard coal

and lignite were estimated at 860 billion tons, which

should ensure their availability: hard coal within a

horizon of 400 years, and lignite within a horizon

of 140 years. Oil reserves, on the other hand, are

estimated at around 182 billion tons, which should

last for around 160 years. In contrast, the world’s

proven natural gas reserves are estimated to be close

to 187 490 cm, i.e. its availability over the next 60

years. As for uranium, its proven reserves are es-

timated at 2.44 million tons. In the perspective of

the next few decades, the estimated resources will de-

crease, with a change in the structure of the use of

individual raw materials. Natural gas is expected to

play an increasingly important role in the economy

and may gradually displace hard coal, lignite and oil

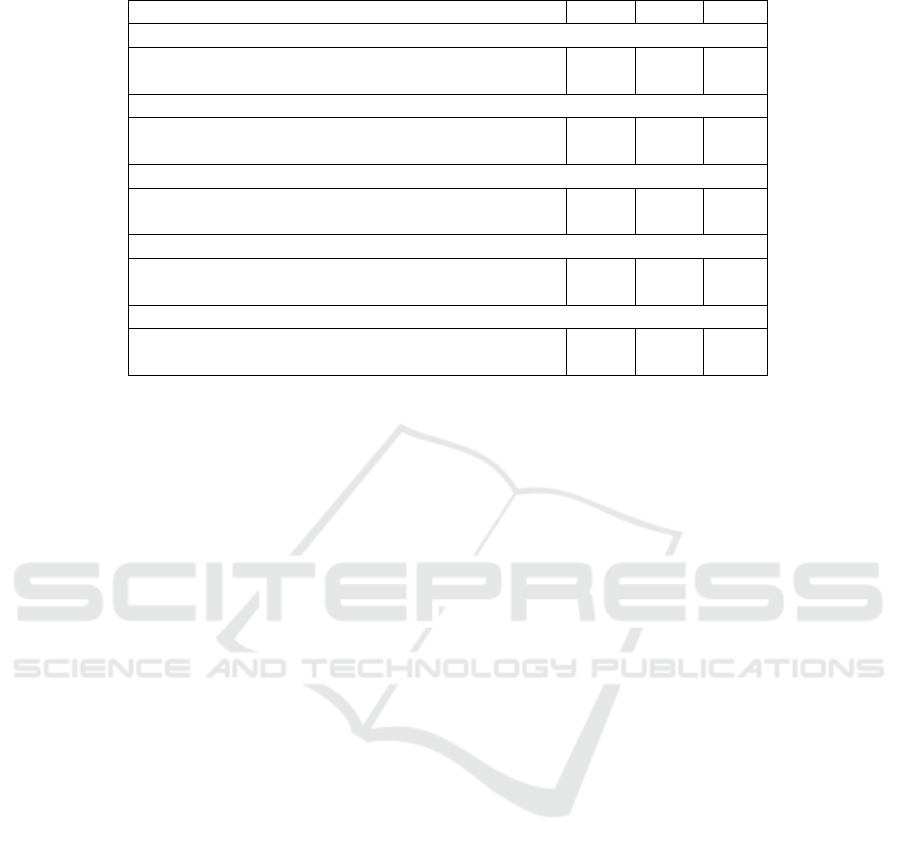

(Wor, 2022). This trend is confirmed by an analysis of

changes in the supply and consumption (extraction) of

energy carriers and changes in the production (extrac-

tion) of major natural resources (table 2). A separate

group of energy raw materials are the so-called re-

newable sources, the resources of which are basically

stable.

The separate major problem of the world econ-

omy is the issue of the exhaustibility of many types

of natural resources as a consequence of their extrac-

tion caused by production needs. It is estimated that

currently identified estimated reserves of fossil raw

materials – treated as primary raw materials – will be

mostly exhausted in the next 60-140 years. A more

optimistic approach to the world’s natural resources

is a dynamic one, based on the belief that these re-

sources do not have a finite size, that they are essen-

tially a function of human knowledge and capacity.

This means giving priority not to the physical size of

natural resources at any given time, but to an aware-

ness of the possibility of meeting needs for them on

the basis of those resources that have already been

identified and those that are yet to be discovered, and

those that can be secondarily recovered.

The solution to the raw material problem – which

is at the same time a global problem – is only pos-

sible with a comprehensive approach to it, that is,

with a combined solution to the raw material prob-

lem with environmental, demographic, food and gen-

eral development issues. Being aware of the rarity of

non-renewable resources and their finiteness, it seems

expedient and desirable to direct human economic ac-

tivity, based on price mechanisms, towards rationality

of conduct, consisting in the search for new technolo-

gies using relatively cheaper resources, the activity of

economic authorities – i.e. the state – towards desir-

able ways of using the environment on the basis of

both administrative and economic instruments: and

towards all those activities which will lead to a physi-

cal reduction of their consumption and the generation

and absorption of energy- and material-saving tech-

niques and technologies (Toffler, 2003).

The problem of the exhaustibility of economic re-

sources at the same time as their increased consump-

tion has forced the reconciliation of economic devel-

opment with the solution of environmental problems,

also in its ecological dimension. At the same time,

this means that the use of the environment, which is

growing along with economic development, is lead-

ing to tensions not only as a result of the increasing

scarcity of natural resources, but also in view of its

destruction and pollution. The consequences of both

natural and technical catastrophes, as well as the con-

sumption behavior of households and investment be-

havior of businesses, contribute to this.

The processes of global economic reproduction –

in the material sphere – are significantly affected by

natural disasters, of which the following should be

mentioned: extreme temperatures and the resulting

droughts and fires, floods and storms, as well as vol-

canic eruptions. These generate considerable mate-

rial damage, often affecting large numbers of people,

some of whom lose their lives. This is indicated by

the data on this phenomenon for the period 1990-2011

(table 3).

One of the natural threats facing the world com-

munity is the phenomenon of warming. This climatic

phenomenon is the result of the world’s increasing in-

dustrialization, urbanization and the way people live.

The increase in heat on Earth is seen by climatolo-

gists as an anomaly caused by the impact of human

civilization and industrial carbon dioxide emissions.

It has been calculated that in 2000, the carbon dioxide

content was 30% more than in 1750. If carbon diox-

ide concentrations were to double by 2100, the Earth’s

average temperature would be expected to rise by 1.9

to 5.2 degrees Celsius. Such a significant warming of

the climate will exacerbate current climate threats and

lead to catastrophe on Earth. The years at the end of

the twentieth century brought an exacerbation of cer-

tain relatively new environmental phenomena, such

as urban air pollution, acid rain, the so-called ozone

hole, the greenhouse effect, sea pollution, drinking

water shortages, declining forest areas and changes in

the world’s biological resources. They are the conse-

quence of human activity and the means it uses. They

are characterized by the fact that they are mostly in-

ternational in scope and global in dimension. They

are all closely linked – in a feedback system – to

economic development and global population growth.

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

112

Table 2: World production of fossil fuels, major natural resources, industrial products and electricity (Roc, 2021).

No Specification 2000 2010 2020

1. Hard coal in million tonnes 3587 6510 6723

2. Oil in million tonne 33447 3615 3928

3. Natural gas 97 127 155

4. Cement in million tonnes 1660 3280 4100

5. Crude steel in million tonnes 849 1034 1319

6. Refined copper in million tonnes 14.8 19 24.5

7. Primary aluminium in million tonnes 24 41.8 65.2

8. Bauxite in million tonnes 236 371

9. Wood (coarse) in hm3 3482 3587 3915

10. Electricity in TWh 15481 21516 27044

Table 3: Natural disasters in the world by type from 1990 to 2011 (Roc, 2021).

SPECIFICATION

Number Fatalities Persons Damage value

of incidents in thousands affected in USD million

Flood 2858 161 2612487 430434

Drought 338 4,5 1192872 64907

Storm (tornado) 2092 386 659609 736218

Earthquake (seismic activity) 603 805 115543 637044

Fire 253 1,6 5548 43541

Extreme temperatures 350 158 96671 48703

Volcanic eruption 120 1,5 3699 559

They also have in common that their consequences

are not fully recognized (Stachowiak and Stachowiak,

2022).

A consequence of natural disasters has been the

growing threat of the extinction of some 11,000 an-

imal species as a result of irreversible environmen-

tal transformation. Specifically, this threat affects

around 25% of all mammal and reptile species, 20%

of aquatic animals, 30% of fish and 12% of birds. The

increase in this phenomenon is confirmed by analy-

ses of the extinction of endangered species. If the

global extinction rate for endangered species (based

on the Red List of Threatened Species) in 2020 was

0.73, the most alarming situation was in Central Asia

(0.93), North Africa (0.87), Europe (0.84) and North

America (0.84). Forests are also at risk of destruction.

According to the World (UN) Food and Agriculture

Organization (FAO), approximately 40 percent of the

world’s old-growth forests could disappear over the

next 10 to 20 years (Roc, 2021).

Numerous technical and technological disasters

also have a significant impact on environmental

degradation. They affect all areas of the globe. They

are the cause of industrial accidents, accidents in non-

industrial facilities and transport accidents (land, sea).

They also affect a significant proportion of the popu-

lation locally, often contributing to their deaths. They

caused damage of a high value, which also necessi-

tated further expenditures for their removal.

In view of this situation, the challenge of the fu-

ture is to address the economic, technical and techno-

logical development of individual national economies

and the global economy as a whole, without destroy-

ing its natural base. The challenge of the future should

be to act pro-ecologically. It is becoming necessary

to reorient the awareness that it is not the progress of

civilization that leads to an ecological disaster, but its

inappropriate use.

In the modern world, environmental degradation

is a threatening and real phenomenon, but not in-

evitable. Mankind has an opportunity to prevent it

effectively. In the first instance, it should learn about

the causes and consequences of environmental degra-

dation and strive to make proper use of the progress of

civilization on a global scale. It is also indispensable

to make full and effective use of all methods and pos-

sibilities of environmental protection. It is also desir-

able to work towards the elimination of technologies

that pollute the environment in a way that endangers

life and health, and instead to disseminate technolo-

gies that do not poison or pollute the environment.

However, this implies a cost. The most synthetic ex-

pression of these should be a reduction in the rate of

economic growth. However, solving the environmen-

tal problem is not only an economic issue, but also a

political and institutional one.

One of the important problems plaguing the world

at the beginning of the third millennium is the issue of

Institutional Economics in the Face of Global Challenges in Europe

113

the regional mismatch between food production and

consumption. If we have a situation of a balanced

world food market on a global scale, however, in some

regions we are dealing with its far-reaching dishar-

mony (table 4). This manifests itself – at close to

equilibrium physical availability – as economic inac-

cessibility to food. As such, it gives rise to numerous

regional and local pockets of malnutrition and hunger.

This situation is influenced by a range of factors, from

climatic to structural, economic and demographic.

When analyzing the physical side of agricultural

production and, consequently, food production, it is

necessary to point out the far-reaching variation in it

across the world. The situation on the African conti-

nent is the worst from this point of view. A far from

satisfactory situation also applies to many countries in

Latin America and Asia. The primary cause appears

to be climatic disturbances: harsh winters, droughts,

floods and storms. The second, also very important, is

the inability of agriculture to increase food supply due

to its backwardness, which is determined by the size

and structure of the stock of arable land and its trends,

technical equipment, mineral fertilization, land recla-

mation, and government food policy. The economic

unprofitability of production is also a frequent cause,

which occurs especially under conditions of increas-

ing energy intensity of production. The fact that agri-

cultural production capacity is being exhausted is also

not insignificant. All these stoppages are reinforced

by the persistence of poverty in many regions of the

world.

The causes of this situation are to be found in par-

ticular in unfavorable changes to climate and soil con-

ditions. They are therefore primarily objective in na-

ture. However, they have also been caused to a large

extent by the overexploitation of pasture and arable

land, increasing demographic pressure and the desire

to increase the production of pro-export monoculture

crops.

Combating these phenomena must be considered

humanity’s most urgent and important task. Solving

this problem is already posing many difficulties today.

It will be all the more difficult to solve in the future in

view of the demographic forecast scenarios. Meet-

ing this problem, even if it is technically possible,

will be limited by factors of an economic, infrastruc-

tural, political and also health nature. At present, the

most important barriers to the growth of agricultural

production are: the inevitable decrease in the area of

agricultural land and, consequently, in the food area;

the failure to comply with agrotechnical principles;

the growing deficit in fresh water; the persistence of

an archaic agrarian structure, as well as low agricul-

tural productivity in many regions of the world; the

occurrence, due to climate change, of the phenom-

ena of floods and droughts leading to food disasters;

the manner of food distribution and the general de-

velopment problems of the global economy (Małysz,

2009).

The phenomenon of hunger and malnutrition is

closely linked to the mismatch between regional food

production and consumption. On the production side,

a range of factors – from climatic to demographic

to economic – influence this. On a global scale, the

existing inequalities in food production and caloric

intake make it possible to divide all countries into

five groups according to food availability. These are:

first - established food powers (14 highly industri-

alized countries); second – new food exporters (in-

cluding Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, Argentina, Rus-

sia, Ukraine); third – self-sufficient countries (ba-

sically: China, India, Pakistan); fourth – importers

of expensive food (Japan, South Korea, Switzerland,

UK, Gulf kingdoms); and fifth – poor and food inse-

cure countries (countries in Central America, Central

Asia, North and Sub-Saharan Africa).

Addressing the food issue requires a number of

undertakings. reflected in the global community’s

pursuit of food security, which boils down to ensuring

the physical and economic availability of food and the

healthiness of food products.

Evaluations into physical access to food indicate

that solving this problem poses many difficulties, and

it becomes all the more difficult in the future. Indeed,

if demographic projections are taken into account,

global food production should increase by 75-100%

over the next 25 years if there is to be enough food for

the entire world population. If meeting this problem

from a technical-agronomic point of view (i.e. physi-

cal availability of food) is possible, it will be limited

by factors of an economic (distribution), infrastruc-

tural, as well as political and health (availability of

healthy food) nature (Górecki and Halicka, 2013).

3.3 Relational Challenges in Europe

By treating the relational challenges as a complement

to the two previously identified population and ma-

terial challenges, it is necessary to give them a bal-

ancing character. They must be seen at the level of

both internal development processes and external de-

velopment processes. They are closely interrelated

and interact with each other. The development of

the world economy is closely linked to the civiliza-

tional development of world society as measured by

scientific, technical, technological and organizational

progress. This is due to the economic international-

ization of the economy and the inclusion of ever wider

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

114

Table 4: Production of the world’s major food resources (Roc, 2021).

SPECIFICATION 2005 2010 2020

WORLD

a. Cereals harvested in million tonnes 2266 2467 2979

b. Meat production from slaughter in million tonnes 260 295 337

Africa

a. Cereal harvest in million tonnes 142 167 204

b. Meat production from slaughter in million tonnes 13.6 16.5 20.7

Central and South America

a. Cereal harvest in million tonnes 57 187 284

b. Meat production from slaughter in million tonnes 39.2 46.1 56.0

Asia

a. Cereal harvest in million tonnes 1087 1227 1435

b. Meat production from slaughter in million tonnes 105.5 123 131

Europe

a. Cereal harvest in million tonnes 427.5 405.5 546

b. Meat production from slaughter in million tonnes 51.9 56.6 64.0

areas of the globe in comparative mechanisms. It is

associated with efforts to expand and increase com-

petitiveness and the search for even more innovative

development strategies. Achieving a civilizational ad-

vantage in these areas involves incurring correspond-

ingly large expenditures (table 5). Its expression is in

the reported inventions of new innovative technolo-

gies and techniques, as well as consumer and invest-

ment products.

The volume of investment in research and devel-

opment activities is constantly increasing. Higher

levels of outlays than the global average is taking

place in North America, East Asia and Europe. Lead-

ing countries (according to 2016 data) are South Ko-

rea (4.23%), Switzerland (3.37%), Sweden (3.25%)

(Japan (3.14%), Austria (3.09%), Germany (2.93%),

Denmark (2.87%), Finland (2.75%) and the USA

(2.74%). Significantly lower levels of outlays as a

proportion of GDP are in: France (2.25%), China

(2.11%), the UK (1.69%) and Russia (1.1%). In con-

trast, the lowest levels of outlays as a proportion of

GDP are in Central Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, South

Asia and North Africa (Roc, 2021).

The variation in the number of outlays on research

and development activities is also evident in Europe.

The European Union countries (27) reached 2.23%

of GDP in 2020, with the euro area countries (19) at

2.26%, and Poland at 1.32% (in 2000 – 0.64%). Re-

ferring to these outlay figures, it should be noted that

an outlay figure of 1% of GDP only means maintain-

ing the current level of R&D activity. The world is far

from its target in this area: according to the Lisbon

Strategy, the European Union countries were to reach

outlays of the order of 3% of GDP by 2010, while ac-

cording to the OECD they should be of the order of

2% of GDP.

The structure of R&D outlays is also far from sat-

isfactory. In underdeveloped countries, outlays on

basic research have tended to dominate, followed by

those on applied research and, to the smallest extent,

on development work. In contrast, in highly devel-

oped countries, outlays on development work domi-