Game Analysis of Manufacturers and Gray Market Speculators

Under Different Government Policies

Fang Zhang

a

and Qianqian Zhang

*b

School of Marketing Management, Liaoning Technical University, Huludao, China

Keywords: Government Policies, Manufacturers, Gray Market Speculators, Stackelberg Game.

Abstract: This article aims to explore the impact of different government policies on the sales of licensed products by

manufacturers and the sales of parallel products by gray market speculators. A market structure with

manufacturers as dominant players and gray market speculators as followers is established. Based on the

Stackelberg game approach, three scenarios are considered in which the government does not implement a

policy, the government implements a subsidy policy for manufacturers, and the government implements a

regulatory policy for gray market speculators. In the three cases, the influence of government subsidy

amount and supervision intensity on the equilibrium solution of manufacturers and gray market speculators

is solved and compared. Research shows that when the government implements subsidy policies, both

manufacturers and gray market speculators will reduce the unit sales price of their products. When the

government implements regulatory policies, manufacturers will increase the unit sales price of licensed

products, and gray market speculators will reduce the sales price of parallel products. Regardless of whether

the government implements subsidies or regulatory policies, it will increase the after-sales service level,

sales volume and profits of manufacturers, and reduce the sales and profits of gray market speculators.

1 INTRODUCTION

1

Gray markets, also known as parallel imports, are

market channels that sell branded goods without the

authorization of the trademark holder (Liu et al.,

2020). Unauthorized sellers are called "gray market

speculators" and goods sold through gray market

speculators are called "gray market products" or

"parallel products". Factors such as volume

discounts implemented by manufacturers and large

fluctuations in exchange rates that cause price

differences in different markets for the same product

are the main reasons why gray markets occur

(Cavusgil et al., 1988). In recent years, with the

rapid development of e-commerce, Internet

technology and globalization of logistics, the gray

market phenomenon has become increasingly

prominent. For example, according to the Financial

Times, in the European Union, the gray market

accounts for billions of dollars in pharmaceutical

sales each year. Kanavos et al. (2004) find that from

1997 to 2002, the share of the gray market in the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2155-6759

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2502-3260

overall pharmaceutical industry increased from less

than 2% to 10.1% in Sweden, from 1.7% to about 7%

in Germany, and from less than 1% to 21.6% in

Greece during the same period. A report released by

a company called iSuppli shows that 145 million

cell phones were shipped in the gray market in 2009,

with a nearly 13% market share of the global cell

phone market, a significant increase of 43.6%

compared to 2008. Gray markets are also found in

other sectors around the world, with the airline

industry, the automotive industry, watches and

jewelry, and beauty and health products all

involving gray market speculators (Wang, 2014).

The increasingly large size of the gray market can

cause a decline in profits from the perspective of

companies. It also reduces consumer satisfaction and

damages brand image in the long run as the quality

of after-sales service for consumers cannot be

guaranteed. From the stakeholder's point of view, it

will make gray market speculators and unscrupulous

black marketers gain higher profits, leading to

chaotic market channels and social harmony in

turmoil. Therefore, it is of some practical

importance to motivate companies to solve the gray

market problem from the government's perspective.

42

Zhang, F. and Zhang, Q.

Game Analysis of Manufacturers and Gray Market Speculators Under Different Government Policies.

DOI: 10.5220/0012069800003624

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis (PMBDA 2022), pages 42-52

ISBN: 978-989-758-658-3

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

The increasingly prominent issue of gray market

has attracted domestic and international scholars to

study it from different perspectives. For example, Su

et al. (2012) find that volume discount contracts and

revenue sharing contracts can reduce retailer

participation in gray market transactions. Hong et al.

(2018) establish compensation contracts to achieve

overall supply chain coordination and incentives in a

gray market environment. Since parallel imports are

a common form of gray market, scholars have also

studied parallel imports and manufacturer channel

choice. For example, Su et al. (2017) based on the

perspective of parallel imports find that

manufacturers' choice of channel depends on the

effects of parallel import costs, the elasticity of

market demand in two countries and production

costs. Hong et al. (2021) construct four channel

structures based on manufacturers selling directly or

distributing in two markets to investigate the

conditions for the existence of gray markets under

different channel structures and the optimal channel

choice for manufacturers. Yeung et al. (2013)

examine how official distribution channels of

multinational companies, asset specificity, limited

rationalization of franchised dealers, and parallel

traders lead to the sustainability of parallel imported

cars. Other scholars have studied gray markets in

terms of pricing and service strategies. For example,

Ahmadi et al. (2000) give manufacturers' pricing

strategies under different conditions by developing a

three-level supply chain model with manufacturers,

gray market speculators, and consumers. The

findings suggest that the presence of gray market

speculators may help manufacturers to expand the

global scope of their products and even increase

their global profits. Iravani et al. (2016) find that the

emergence of gray markets leads manufacturers to

increase service levels in both high- and low-price

markets and that service decisions can be used as a

non-price mechanism to manage gray markets. Rong

et al. (2020) consider a multinational manufacturer

and a local manufacturer selling products to two

independent markets and compare and analyze the

effects of different power structures on supply chain

members' pricing and profits with and without gray

markets. In addition, it has been found that RFID

technology (Ding et al., 2022), manufacturers'

after-sales service quality decisions (Hu et al., 2021),

and brands' remanufacturing decisions (Huang et al.,

2020) can be used to manage and control gray

markets.

Throughout the literature, manufacturers'

after-sales service quality decisions (Iravani et al.,

2016; Hu et al., 2021) can be an effective tool for

managing gray markets, but few scholars have

incentivized firms to improve after-sales service

quality from the government's perspective to address

the gray market problem. Most of the scholars are

combining government policies with green supply

chain and closed-loop supply chain. For example,

Shang et al. (2020) construct a green supply chain

model in which the government subsidizes R&D

costs and production costs, respectively, and find

that both government subsidy strategies positively

affect product greenness, sales volume, and supply

chain members' profits. Cao et al. (2020) establish

three scenarios based on secondary supply chains

with no government subsidies, government subsidies

for manufacturers, and government subsidies for

retailers. The results show that government subsidies

can stimulate the green effort behavior of

manufacturers and retailers, which is always

beneficial to the green development of the supply

chain. Xia et al. (2017) analyze the impact of

government adoption of subsidy policy, adoption of

regulatory policy, and no policy on the reverse

recycling of end-of-life vehicles in formal and

informal channels in three cases. Although Wu

(2017) studies the impact of government regulatory

policies on manufacturers in the presence of gray

markets, the relationship between government

subsidy policies and gray markets is not studied.

In view of this, this paper considers the existence

of a manufacturer and a gray market speculator in

the market, constructs three different scenarios in

which the government does not implement a policy,

the government implements a subsidy policy for the

manufacturer, and the government implements a

regulatory policy for the gray market speculator, and

uses a dominant-subordinate game approach to

study the decision problem of different government

policies for the manufacturer and the gray market

speculator, respectively.

2 MODEL INTRODUCTION

2.1 Model Description

In this paper, we consider a market structure with a

manufacturer (denoted as M) as the dominant player

and a gray market speculator (denoted as A) as the

follower. The manufacturer sells a licensed product

to consumers through an authorized channel at price

m

p

, and the gray market speculator sells a parallel

product to consumers through an unauthorized

channel at price

a

p

. In contrast to gray market

Game Analysis of Manufacturers and Gray Market Speculators Under Different Government Policies

43

speculators, manufacturers need to provide

after-sales services to consumers. The government,

in order to motivate manufacturers to provide

after-sales services and to reduce arbitrage by gray

market speculators, has considered three scenarios:

no government policy, a government policy of

subsidies to manufacturers, and a government policy

of regulation of gray market speculators.

2.2 Model Assumptions

(1) Assume that the manufacturer's cost of providing

after-sales service is

2

2

ks

, where k indicates the

manufacturer's after-sales service cost factor.

(2) Although both licensed and parallel products

are genuine in the market, parallel products do not

have access to after-sales service, quality assurance,

etc., and their perceived product quality is lower than

that of licensed products. Therefore, it is assumed

that in the market, the perceived quality of the

licensed product is 1 and the perceived quality of the

parallel product is

θ

( 10 <<

θ

).

(3) Assume that the consumer can only purchase a

maximum of one product.

(4) Denote consumers' marginal willingness to

pay for the perceived quality of a product by

x

. Let

x

obey a uniform distribution of

[

]

0,1 , which yields

the consumer's perceived value of the licensed

product as

x

and the perceived value of the parallel

product as x

θ

.

(5) Assume that transportation costs, production

costs, etc. are all zero.

2.3 Description of Symbols

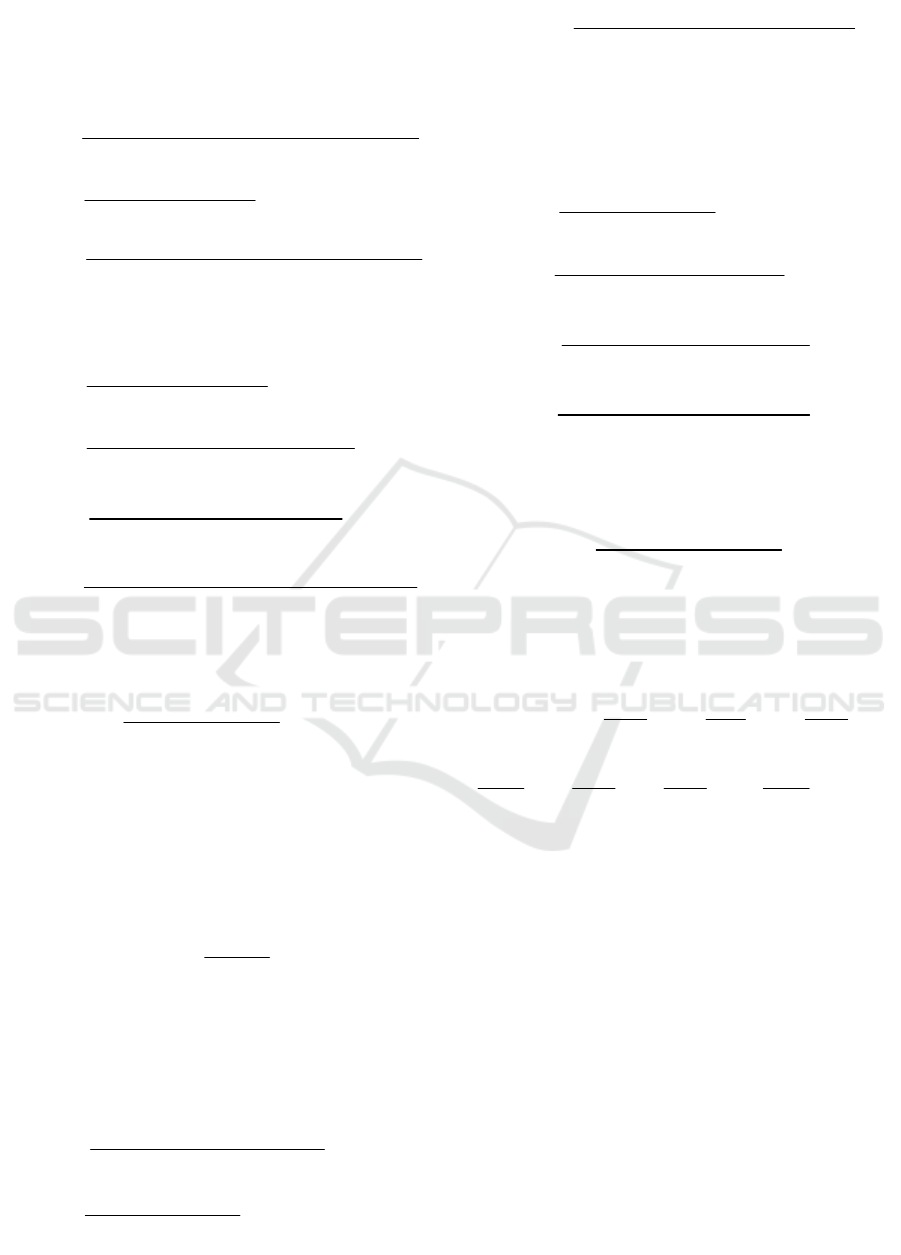

Table 1: Symbol settings and their descriptions.

Symbol Symbol description

n

Government does not implement policies

v

Government imposes subsidy policy on

manufacturers, unit subsidy amount

τ

Government imposes regulatory policy on

g

ra

y

market s

p

eculators, unit re

g

ulation

o

m

s

The after-sales service level of a

manufacturer when the government

implements policy o, where

{

}

,,onv∈τ

o

m

p

The unit selling price of a manufacturer

selling a licensed product when the

government implements policy o, where

{

}

,,onv∈τ

S

y

mbol S

y

mbol descri

p

tion

o

a

p

The unit selling price of a gray market

speculator selling a parallel product when

the government implements policy o, where

{

}

,,onv∈τ

o

m

q

The number of sales of licensed products

sold by manufacturers when the

government implements policy o, where

{

}

,,onv∈τ

o

a

q

The number of sales of parallel products

sold by speculators in the gray market when

the government implements policy o, where

{

}

,,onv∈τ

o

m

π

Manufacturer's profit on the sale of licensed

products when the government implements

policy o, where

{

}

,,onv∈τ

o

a

π

The profits of gray market speculators from

the sale of parallel products when the

government implements policy o, where

{

}

,,onv∈τ

o

m

u

The utility function of a consumer

purchasing a licensed product when the

government implements policy o, where

{

}

,,onv∈τ

o

a

u

The utility function of a consumer's

purchase of a parallel product when the

government implements policy o, where

{

}

,,onv∈τ

2.4 Demand Function Creation

2.4.1 Government Non-Implementation

Policy and Government

Implementation of Subsidy Policy

According to the assumptions, the utility function of

a consumer purchasing a licensed product is

expressed as

=− +

ooo

mmm

uxps

and the utility

function of a consumer purchasing a parallel product

is expressed as

=θ −

oo

aa

uxp

, respectively, where

{

}

,∈onv . When the utility function

,0≥≥

ooo

mam

uuu

, the consumer chooses to buy the

licensed product; when

,0≥≥

ooo

ama

uuu

, the

consumer chooses to buy the parallel product. At this

point the demand function is

1

1

θ

−−

=−

−

ooo

o

mam

m

p

ps

q

(1)

PMBDA 2022 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

44

1

θθ

−−

=−

−

ooo o

o

mam a

a

p

ps p

q

(2)

2.4.2 Government Implementation of

Regulatory Policies

According to the assumptions, the utility function of

consumers purchasing licensed products is

τττ

=− +

mmm

uxps

, and the utility function of

consumers purchasing parallel products is

ττ

=θ − −τ

aa

uxp

. When the utility function

,0

τττ

≥≥

mam

uuu

, the consumer chooses to buy the

licensed product; when

,0

ττ

≥≥

o

ama

uuu

, the

consumer chooses to buy the parallel product. At this

point the demand function is

1

1

θ

τττ

τ

−−−τ

=−

−

mam

m

pps

q

(3)

1

θθ

τττ τ

τ

−−−τ +τ

=−

−

mam a

a

pps p

q

(4)

3 MODEL SOLVING

3.1 Government Non-Implementation

Policy

The government has neither a subsidy policy for

manufacturers nor a regulatory policy for gray

market speculators. At this point, the profit functions

for the manufacturer and the gray market speculator

are

2

()

(,)

2

π

=−

n

nnn nn

m

mmm mm

ks

ps pq

(5)

()

π

=

nn nn

aa aa

ppq

(6)

Theorem 1: In the absence of government

intervention, the optimal solution for manufacturers

and gray market speculators is

2

4(1 )

(2 )(4k 4k 2)

θ

θθθ

∗

−

=

−+−−

n

m

k

p

2(1 )

442

θ

θθ

∗

−

=

+− −

n

m

s

kk

(1 )( 2 k 2 2 )

(2 )(4k 4k 2)

θθ θ θ

θθθ

∗

−+−−

=

−+−−

n

a

k

p

Substituting

∗

n

m

p ,

∗

n

m

s and

∗

n

a

p into equations

(1) (2) (5) (6), we get

2(1 )

442

θ

θθ

∗

−

=

+− −

n

m

k

q

kk

222

(2 )(4k 4k 2)

θθ

θθθ

∗

+− −

=

−+−−

n

a

kk

q

2

(2 2)

2(2 )(4 k 4 k 2)

θ

π

θθθ

∗

−

=

−+−−

n

m

k

2

22

(1 )( 2 2 2 )

(2)(4 4 2)

θθ θ θ

π

θθθ

∗

−+−−

=

−+−−

n

a

kk

kk

Proof 1: According to the reverse solution method,

n

a

p

is solved first. Since

2

2

2

0

() ( 1)

π

θθ

∂

=<

∂−

n

a

n

a

p

, it

is known that

π

n

a

has a great value about

n

a

p

. Let

0=

∂

∂

n

a

n

a

p

π

and solve for

()

2

θ

−

=

nn

n

mm

a

ps

p

.

Substituting

n

a

p

into

π

n

m

, we find the Hessian

matrix of

π

n

m

with respect to

n

m

p

and

n

m

s

as

22

12(1)

2

2( 1)

θθ

θθ

θ

θ

−−

−−

=

−

−

−

H

k

.

When

0244 >−−+

θ

θ

kk

, we have

1

2

0

1

θ

θ

−

=<

−

H

and

2

2

(2)(4 4 2)

0

4( 1)

θθθ

θ

−− +− −

=>

−

kk

H

.

It is known that the matrix

H

is negative definite

and

π

n

m

has great values with respect to

n

m

p

and

n

m

s

. We combine

0=

∂

∂

n

m

n

m

p

π

and

0=

∂

∂

n

m

n

m

s

π

to

obtain the values of

n

m

p

and

n

m

s

. Substitute them

back into

()

2

θ

−

=

nn

n

mm

a

p

s

p

to obtain the optimal

solution for

n

a

p

. The proof is complete.

3.2 Government Subsidy Policies for

Manufacturers

The profit functions for manufacturers and gray

market speculators when the government implements

a subsidy policy for manufacturers are

2

()

(p , ) ( )

2

π

=+ −

v

vvv v v

m

mmm m m

ks

spvq

(7)

Game Analysis of Manufacturers and Gray Market Speculators Under Different Government Policies

45

()

π

=

vv vv

aa aa

ppq

(8)

Theorem 2: In the case of a government subsidy

policy for manufacturers, the optimal solution for

manufacturers and gray market speculators is

22

4(1 ) [(2 ) 2( 1)(2 )]

(2 )(4k 4k 2)

θθθθ

θθθ

∗

−+ −+ − −

=

−+−−

v

m

kv k

p

2(1 ) v(2 )

442

θθ

θθ

∗

−+ −

=

+− −

v

m

s

kk

(1 )( 2 k 2 2 2)

(2 )(4k 4k 2)

θθ θ θ θ

θθθ

∗

−+−−+−

=

−+−−

v

a

kkvkv

p

Substituting

∗

v

m

p ,

∗

v

m

s and

∗

v

a

p into equations

(1) (2) (7) (8), we obtain

(2 2 2 )

442

θθ

θθ

∗

−+−

=

+− −

v

m

kvv

q

kk

222 2

(2 )(4k 4k 2)

θθ θ

θθθ

∗

+− − + −

=

−+−−

v

a

kkkvkv

q

2

(2 2 2)

2(2 )(4 k 4k 2)

θθ

π

θθθ

∗

−+−

=

−+−−

v

m

kvv

2

22

(1 )(2 2 2 2)

(2)(4 4 2)

θθ θ θ θ

π

θθθ

∗

−+−−+−

=

−+−−

v

a

kkkvkv

kk

Proof 2: The proof procedure is the same as in

Proof 1 and is therefore omitted. It should be noted

that the condition for the existence of the optimal

solution is

22 2

(2 )

kk

v

k

θθ

θ

−+−

<

−

.

3.3 Government Regulatory Policies

for Gray Market Speculators

The profit function for manufacturers and gray

market speculators when the government imposes a

regulatory policy on gray market speculators is

2

()

(,)

2

τ

τττ ττ

π

=−

m

mmm mm

ks

ps pq

(9)

()

ττ ττ

π

=

aa aa

ppq

(10)

Theorem 3: The optimal solution for

manufacturers and gray market speculators in the

case of a government policy of regulation of gray

market speculators is

2( 1)(2 2 )

(2)(4 4 2)

τ

θτθ

θθθ

∗

−+−

=

−+−−

m

kk k

p

kk

22

442

τ

τθ

θθ

∗

−+

=

+− −

m

s

kk

(1)

(2)(4 4 2)

τ

θ

θθθ

∗

−

=

−+−−

a

m

p

kk

Where

τθθθ

τ

θ

θ

τ

θ

τ

kk

kkm

32

2422

22

++

−−+−−=

Substituting

∗

τ

m

p ,

∗

τ

m

s and

∗

τ

a

p into equations

(1) (2) (9) (10), we obtain

(22)

442

τ

τθ

θθ

∗

−+

=

+− −

m

k

q

kk

(2 )(4 4 2)

τ

θθ θ θ

∗

=

−+−−

a

m

q

kk

2

(22)

2( 2)(4 4 2)

τ

τθ

π

θθθ

∗

−−+

=

−+−−

m

k

kk

2

22

(1 )

(2)(4 4 2)

τ

θ

π

θθ θ θ

∗

−

=

−+−−

a

m

kk

Proof 3 The proof procedure is the same as in

Proof 1 and is therefore omitted. It should be noted

that the condition for the existence of the optimal

solution is

(2 2 2)

43 2

θθθ

τ

θθ

−+−

<

−+−

kk

kk

.

4 MODEL ANALYSIS

Proposition 1: 0

∗

∂

<

∂

v

m

p

v

, 0

∗

∂

>

∂

v

m

s

v

, 0

∗

∂

>

∂

v

m

q

v

,

0

π

∗

∂

>

∂

v

m

v

; 0

∗

∂

<

∂

v

a

p

v

, 0

∗

∂

<

∂

v

a

q

v

, 0

π

∗

∂

<

∂

v

a

v

.

Proposition 1 suggests that the government's

subsidy policy for manufacturers will result in a

decrease in the manufacturer's unit sales price for

selling licensed products and an increase in the level

of after-sales service, product sales and profits for

manufacturers selling licensed products. At the same

time, it will lead to a decrease in the unit selling price,

sales volume and profits of gray market speculators

selling parallel products. The main reason for this is

that manufacturers increase the number of licensed

products sold by lowering the unit sales price of

licensed products in order to receive more

government subsidies, at which point the

manufacturer's profit increases by selling more at a

lower price. As a result of this increase in profits,

manufacturers are more motivated to provide better

quality after-sales service to their customers. Gray

market speculators will reduce the selling price of

parallel products in order to maintain their original

PMBDA 2022 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

46

competitive advantage, but the sales volume will be

partially reduced due to the impact of government

subsidies, which ultimately leads to a reduction in

profits for gray market speculators.

Proposition 2:

0

τ

τ

∗

∂

>

∂

m

p

,

0

τ

τ

∗

∂

>

∂

m

s

,

0

τ

τ

∗

∂

>

∂

m

q

,

0

τ

π

τ

∗

∂

>

∂

m

,

/

1

/

τ

τ

τ

τ

∗

∗

∂∂

<

∂∂

m

m

s

p

;

0

τ

τ

∗

∂

<

∂

a

p

,

*

0

τ

τ

∂

<

∂

a

q

,

0

τ

π

τ

∗

∂

<

∂

a

.

Proposition 2 suggests that the government's

implementation of regulatory policies on gray

market speculators will increase the unit sales price,

after-sales services level, sales volume and profit of

licensed products sold by manufacturers, and the

increase in service level is smaller than the increase

in price. For gray market speculators, government

regulation will simultaneously reduce the unit sales

price, sales volume and profit of the parallel product.

The main reason for this is that when the government

imposes regulatory policies on gray market

speculators, it reduces the competition between

manufacturers and gray market speculators, allowing

manufacturers to restore the prices of licensed

products in the market and sell them in the market at

high prices. Although manufacturers will increase

costs by raising after-sales service levels as

regulation increases, manufacturers can increase their

profits with government protection as the increase in

after-sales service levels is less than the increase in

price. When the government implements regulatory

policies, it causes some consumers who buy parallel

products to switch to buying licensed products, and

gray market speculators sell fewer parallel products.

To prevent a reduction in demand for their products,

gray market speculators will continue to reduce the

unit selling price of their parallel-imported products,

ultimately leading to a reduction in their profits.

Proposition 3: When

v

v

≥

(

22 2

(2 )

θθ

θ

−+−

=

−

kk

v

k

), then

0

∗

≤

v

a

q

. When

τ

τ

≥ (

(2 2 2)

43 2

θθθ

τ

θθ

−+−

=

−+−

kk

kk

), then 0

τ

∗

≤

a

q

and

0

τ

−<v

.

Proof 4: By

0

∗

∂

<

∂

v

a

q

v

, we know that the quantity

of parallel products sold by gray market speculators

will fall to a demand of 0 as the amount of

government subsidy increases, i.e. 0

∗

=

v

a

q , and we

get

22 2

(2 )

θθ

θ

−+−

=

−

kk

v

k

. Similarly, by

0

τ

τ

∗

∂

<

∂

a

q

,

we know that the number of gray market speculators

selling parallel products will fall to a demand of 0 as

government regulation increases. i.e.

0

τ

∗

=

a

q

, we

get

(2 2 2)

43 2

θθθ

τ

θθ

−+−

=

−+−

kk

kk

. In addition, we can

conclude that

2

(2 2 2)(4 5 2)

0

(2)(4 3 2)

θθ θθθ

τ

θθθ

+− − +− + −

−= <

−+−−

kk kkk

v

kkk

.

Proposition 3 suggests that whether the

government implements a regulatory or a subsidy

policy, gray market speculators will choose to exit the

market when either the level of regulation or the

amount of subsidy reaches a certain level. For the

government, it takes less effort to implement a

regulatory policy than a subsidy policy to fully

combat and regulate the gray market.

Proposition 4:

2

2

43 2

,

,

,

τ

ττ

ττ

ττ

τθθ

θθ

ππππππ

∗∗∗

∗∗∗∗∗∗

∗∗∗∗∗∗

∗∗∗∗∗∗

−

<

−+−

>>

>> >>

>> >>

>> >>

vn

mmm

nvn v

mmma a a

vnnv

mmma a a

vnnv

mmma a a

kk

vkk

sss

pppppp

qqqqqq

;

2

2

2

43 2

,

,

,

τ

ττ

ττ

ττ

θθ τ

θ

θθ

ππππππ

∗∗∗

∗∗∗∗∗∗

∗∗∗∗∗∗

∗∗∗∗∗∗

−

≤≤−

−+−

≥>

>> >≥

≥> >≥

≥> >≥

vn

mmm

nvnv

mmma a a

vnnv

mmma a a

vnnv

mmma a a

kk

kk v

sss

pppppp

qqqqqq

;

2

,

,

,

vn

mmm

nvnv

mmma a a

vnnv

mmma a a

vnnv

mmma a a

v

sss

pppppp

qqqqqq

τ

ττ

ττ

ττ

τ

θ

ππππππ

∗∗∗

∗∗∗∗∗∗

∗∗∗∗∗∗

∗∗∗∗∗∗

>−

>>

>> >>

>> >>

>> >>

.

Proposition 4 suggests that, for the manufacturer,

we obtain the following conclusion:

(1) From the manufacturer's after-sales service

level, when the ratio of government regulation to the

amount of government subsidy satisfies

/2

τθ

<−v , the manufacturer provides the highest

Game Analysis of Manufacturers and Gray Market Speculators Under Different Government Policies

47

level of after-sales service when the government

implements a subsidy policy, followed by the

implementation of a regulatory policy and the lowest

when no policy is implemented. This is because

government-imposed subsidy policies can cover the

after-sales service costs of manufacturers, resulting

in the highest level of after-sales service. Compared

with the government does not implement the policy,

the manufacturer's after-sales services level is higher

when the government implements the regulatory

policy, in order to attract consumers to change from

unauthorized channels to authorized channels,

thereby supporting licensed products. Whichever

policy the government implements, it will help to

improve the level of after-sales service for

manufacturers.

(2) In terms of manufacturer prices for the sale of

licensed products, manufacturer unit sales prices are

highest when the government implements a

regulatory policy, followed by no policy and lowest

when a subsidy policy is implemented. The main

reason is that when the government implements a

subsidy policy, manufacturers will increase their

sales volume by reducing their prices in order to

obtain more government subsidies. When the

government imposes a regulatory policy, competition

between manufacturers and gray market speculators

is reduced. This will eliminate the need for

manufacturers to reduce their unit selling prices,

which are greater than they would be if the

government did not implement the policy.

(3) In terms of sales of licensed products by

manufacturers, when the ratio of government

regulation to the amount of government subsidy

satisfies /2

τθ

<−v , the number of sales by

manufacturers is highest when the government

implements the subsidy policy, followed by the

implementation of the regulation policy and lowest

when the policy is not implemented. The reason is

that when the government implements the subsidy

policy, the manufacturer has the lowest unit sales

price and the highest level of after-sales service,

resulting in the highest number of sales. When the

government imposes a regulatory policy, the

manufacturer has the highest unit sales price and the

second highest level of after-sales service. Although

the manufacturer's unit sales price is higher than it

would have been in the absence of the government's

policy, the government's regulation of gray market

speculators has resulted in a shift of consumers to the

authorised channel, ultimately resulting in higher

sales than would have been the case in the absence of

the government's policy. Manufacturer profits are not

discussed here as they change in line with changes in

their sales volumes.

For gray market speculators, the conclusions we

can draw are as follows:

(1) From the perspective of the price of parallel

products sold by gray market speculators, when the

ratio of government supervision to government

subsidy amount meets

2

2

/

43 2

θθ

τ

θθ

−

<

−+−

kk

v

kk

,

the sales price of gray market speculators is the

highest when the government does not implement

policies, followed by the implementation of

regulatory policies, and the lowest is the

implementation of subsidy policies. The main reason

for this is that both government regulation and

subsidy policies are unfavourable to gray market

speculators, who will then lower their unit sales

prices in order to maintain their competitive

advantage. Compared with government supervision,

as the amount of subsidies increases, gray market

speculators will sell parallel products at lower prices.

(2) From the perspective of the sales volume of

parallel products sold by gray market speculators,

when the ratio of government supervision to

government subsidies meets

2

2

/

43 2

θθ

τν

θθ

−

<

−+−

kk

kk

, the sales volume of gray

market speculators is the highest when the

government does not implement policies, followed

by the implementation of regulatory policies, and the

least is the implementation of subsidy policies. The

main reason is that compared to government

regulation, when the subsidy is greater than a certain

value, the government subsidy is most beneficial to

the manufacturer, causing more consumers to turn to

authorized channels, and ultimately leading to the

lowest sales volume of gray market speculators.

Since the relationship between the quantity sold

and the profit of a gray market speculator satisfies

2

(1 )( )

πθ θ

=−

ii

aa

q

,

{,,}

τ

∈inv

, the change in the

profit of a gray market speculator is consistent with

the change in the quantity it sells.

PMBDA 2022 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

48

5 NUMERICAL ANALYSIS

The above model mainly analyses the optimal

strategies of manufacturers selling licensed products

and gray market speculators selling parallel products

under different policies implemented by the

government. In the following, the relevant

parameters of the model are taken to further analyse

and verify the relevant findings of this paper.

According to Wu (2017), we assume that the

parameter

0.25

θ

=

and take

1.5=k

in order

to ensure that the hypothesis

2

2(1 )

θ

θ

−

>

−

k

holds.

At this point, we can get

2

2

0.21

43 2

θθ

θθ

−

=

−+−

kk

kk

and

21.75

θ

−=

. Since the change in sales of

manufacturers and gray market speculators

coincides with the change in profits, the portrayal

and analysis of profits is omitted below.

5.1 The Impact of Government

Subsidies and Regulatory Policies

on the Unit Sales Prices of

Manufacturers and Gray Market

Speculators

As seen in Figure 1, as the amount of government

subsidies increases, the unit sales price of licensed

and parallel products will continue to decrease. As

government regulation increases, the unit sales price

of licensed products continues to increase and the

unit sales price of parallel products continues to

decrease. Neither regulation nor subsidy policies

imposed by the government are favourable to gray

market speculators and will result in gray market

speculators reducing their unit sales prices.

For the unit sales price of licensed products, the

price is from highest to lowest: government-imposed

regulatory policy, government-imposed no policy,

government-imposed subsidised policy. For the unit

sales price of a parallel product, when 𝜏/𝑣 >0.21,

the price is from highest to lowest:

government-imposed no policy, government-

imposed subsidised policy, government-imposed

regulatory policy. When 𝜏/𝑣 0.21, the price goes

from high to low: government-imposed no policy,

government-imposed regulatory policy,

government-imposed subsidised policy.

Figure 1: Impact of government subsidies and regulatory policies on unit sales prices.

5.2 Impact of Government Subsidies

and Regulatory Policies on Sales

Volumes of Manufacturers and

Gray Market Speculators

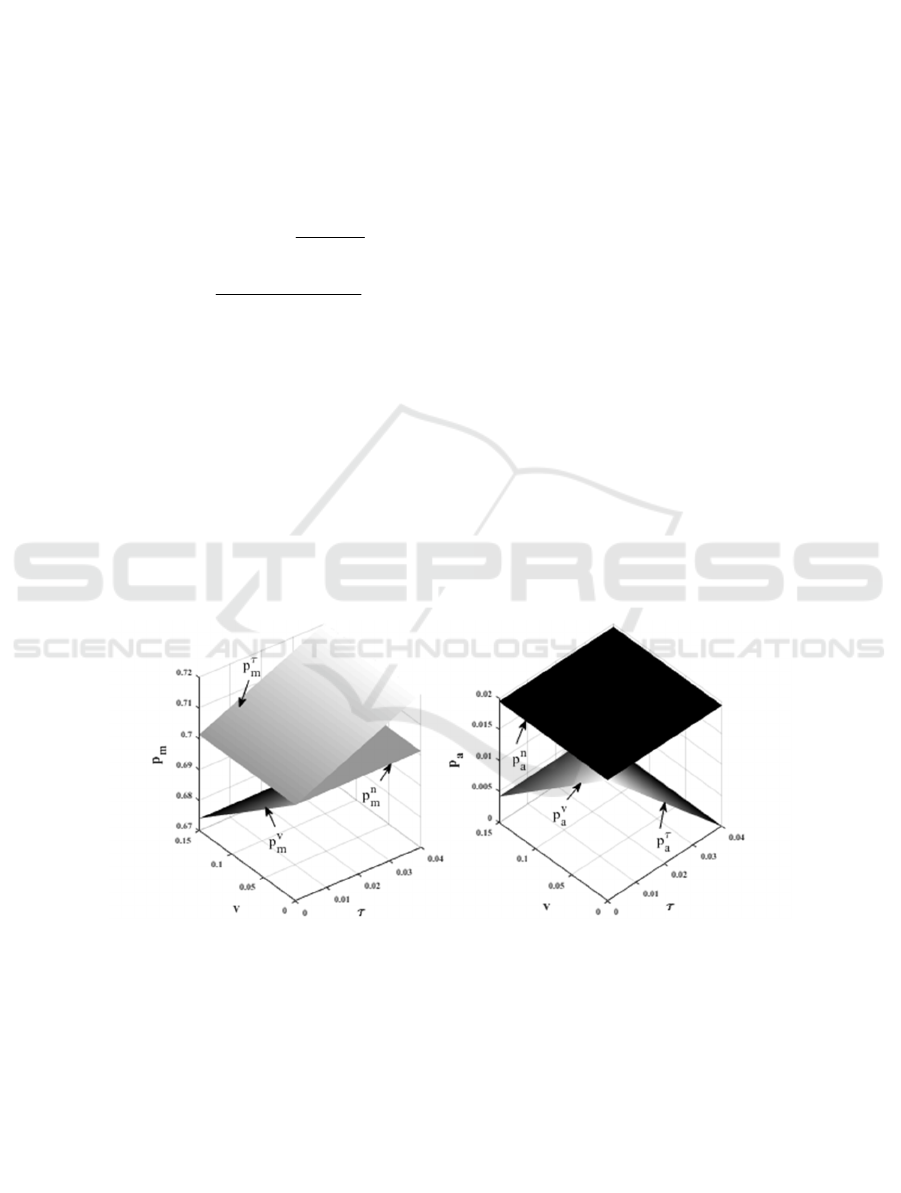

As seen in Figure 2, sales of licensed products have

been increasing and sales of parallel products have

been decreasing as the amount of government

subsidies or regulation has increased.

For the number of licensed products sold by

manufacturers, when 𝜏/𝑣 >1.75, the number of

sales goes from high to low: government-imposed

regulatory policy, government-imposed subsidy

policy, and government-imposed no policy; when

𝜏/𝑣 1.75, the number of sales goes from high to

low: government-imposed subsidy policy,

government-imposed regulatory policy, and

government-imposed no policy. For the number of

Game Analysis of Manufacturers and Gray Market Speculators Under Different Government Policies

49

gray market speculators selling parallel products,

when 𝜏/𝑣 >0.21, the number of sales goes from

high to low: no government policy, government

policy of subsidies, government policy of regulation;

when 𝜏/𝑣 0.21, the number of sales goes from

high to low: no government policy, government

policy of regulation, government policy of subsidies.

Figure 2: Impact of government subsidies and regulation on sales volumes.

5.3 The Impact of Government Subsidies

and Regulatory Policies on

Manufacturers' after-Sales Service

Levels

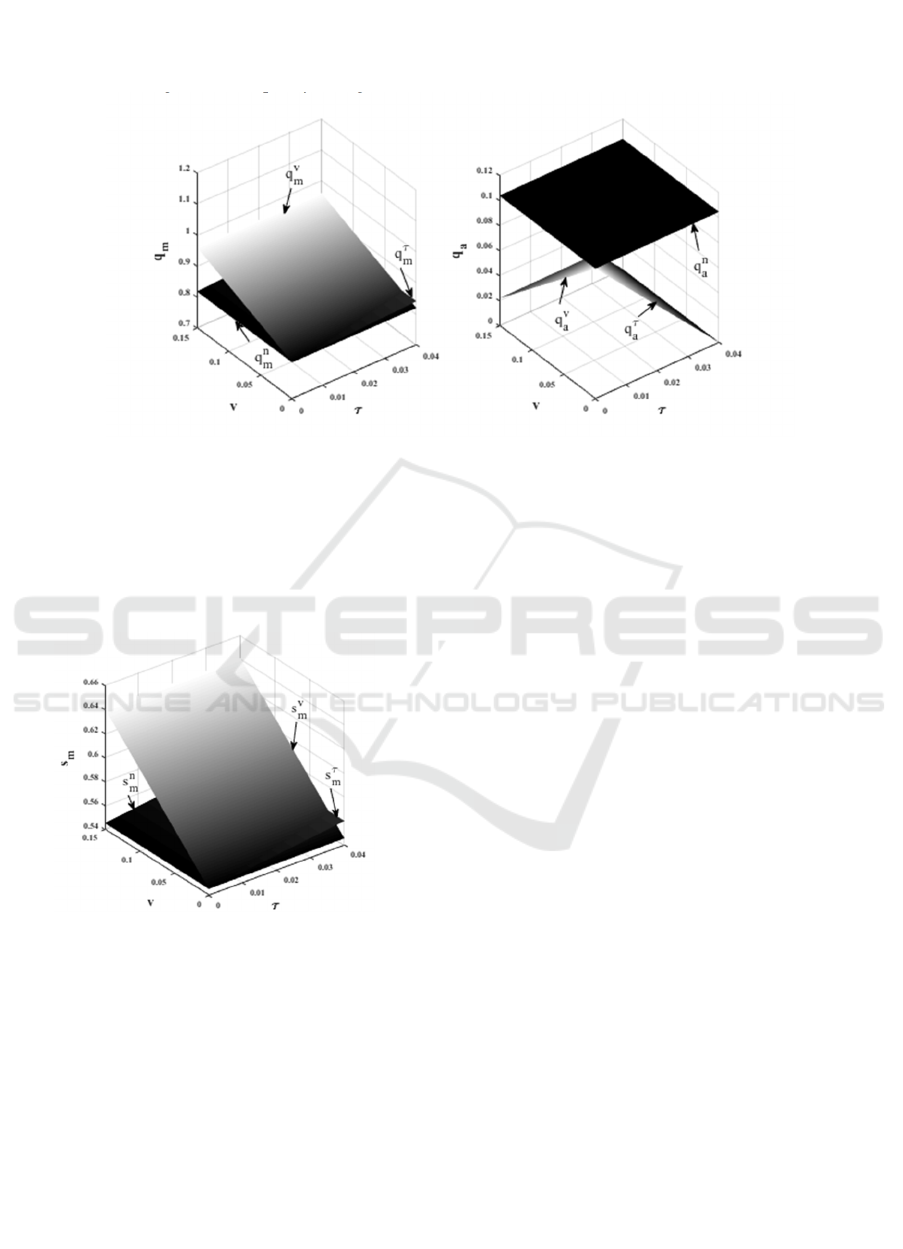

Figure 3: The impact of government subsidies and

regulatory policies on manufacturers' after-sales service

levels.

As seen in Figure 3, the level of manufacturer

after-sales service increases as the amount of

subsidy or regulation increases. When

/1.75

τ

>v

,

the level of service goes from high to low:

government-imposed regulatory policy, government-

imposed subsidy policy, and government-imposed

no policy; when

/1.75

τ

<v

, the level of service

goes from high to low: government-imposed subsidy

policy, government-imposed regulatory policy, and

government-imposed no policy.

6 CONCLUSION

We consider a market in which manufacturers sell

licensed products and gray market speculators sell

parallel products. Based on the three scenarios of no

government policy, government subsidy policy for

manufacturers and government regulatory policy for

gray market speculators, a game model with

manufacturers as dominant players and gray market

speculators as followers is developed to solve and

analyse the impact of different government policies

on each equilibrium solution for manufacturers and

gray market speculators. The study shows the

following.

(1) As the amount of government subsidies

increases, the unit selling price of manufacturers

selling licensed products will decrease and their

sales volume and profits will increase. The unit sales

price, quantity and profit of parallel products sold by

gray market speculators will be reduced. With

increased government regulation, the unit sales price,

sales volume and profits of manufacturers selling

licensed products have increased and the unit sales

price, sales volume and profits of gray market

speculators selling parallel products have decreased.

Both government subsidies and regulatory policies

can improve the level of after-sales service for

manufacturers.

(2) For manufacturers, the unit sales price of

licensed products is highest under

government-imposed regulatory policies, followed

PMBDA 2022 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

50

by no government-imposed policies, and lowest by

government-imposed subsidy policies. When the

ratio of unit regulation to unit subsidy is greater than

a certain threshold value (i.e.

/2

τθ

>−v

), the

highest level of sales, profits and after-sales service

of licensed products is achieved when the

government implements a regulation policy, the

second highest level of sales, profits and after-sales

service is achieved when the government

implements a subsidy policy, and the lowest level of

sales, profits and after-sales service is achieved

when the government does not implement a policy.

Conversely, sales, profits and service levels of

licensed products are highest when the government

implements a subsidy policy, second highest when

the government implements a regulatory policy and

lowest when the government does not implement a

policy.

(3) For gray market speculators, when the ratio

of government unit regulation to unit subsidy is

greater than a certain threshold value (i.e. 𝜏/𝑣 >

), the unit sales price, sales volume and

profit of the parallel product is highest when the

government does not implement the policy, the unit

sales price, sales volume and profit is second highest

when the government implements the subsidy policy,

and the unit sales price, sales volume and profit is

lowest when the government implements the

regulation policy. Conversely, the unit sales price,

sales volume and profit of a parallel product are

highest when the government does not implement a

policy, second highest when the government

implements a regulatory policy and lowest when the

government implements a subsidy policy.

The above research has some implications for

government and business control of gray market

transactions, but there are still many shortcomings:

for example, firstly, this paper only considers the

case where the demand function is deterministic,

and there are real-life cases where demand is

uncertain. Secondly, the paper does not break down

gray market speculators, and future research could

consider the entry of retailers into the gray market

separately.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is one of the achievements of the

National Social Science Fund project "Research on

Online Behavior Mode of Rural Consumers Based

on Social Identity" (project number: 19BGL108)

and the Human and Social Sciences Research

Project of Liaoning Education Department

"Research on Recycling and Remanufacturing of

New Energy Vehicle Power Battery Based on Game

Theory" (project number: 21-A827).

REFERENCES

Ahmadi, R., Yang, B. R., 2000. Parallel imports:

challenges from unauthorized distribution channels.

Marketing Science 19(3), 279-294.

Cao, Y., Xun, J., Li, Q., 2020. A comparative study of

green efforts in supply chain based on different

government subsidy strategies. Operations Research

and Management Science 29(5), 108-118.

Cavusgil, S. T., Sikora, E., 1988. How multinationals can

counter gray market imports. Columbia Journal of

World Business 23(4), 75-85.

Ding, L., Hu, B., Chang, S., 2022. Dynamic game analysis

of manufacturer RFID adoption and retailer parallel

importation. Chinese Journal of Management Science

30(8), 82-94.

Hong, D., Ma, Y., Ni, D., 2018. Compensation strategy for

supply chain coordination in gray markets. Journal of

Systems Engineering 33(1), 103-115.

Hong, D. J., Fu, H., Wan, N.N., Fan, J. C., 2021. Gray

markets and manufacturer’s channel structure

selection. Industrial Engineering and Management

26(1), 61-67.

Hu, B., Ding, L., Hu, S., Feng, Y. H., 2021. The impact of

manufacturer service provision on retailer parellel

importation. Chinese Journal of Management Science

29(7), 46-56.

Huang, F., He, J., Lei, Q., 2020. Remanufacturing as a

competitive strategy to counter parallel importation in

cross-regional trade. Control and Decision 35(9),

2189-2198.

Iravani, F., Dasu, S., Ahmadi, R., 2016. Beyond price

mechanisms: how much can service help manage the

competition from gray markets?. European Journal of

Operational Research 252(3), 789-800.

Kanavos, P., Costa-I-Font, J., Merkur, S., Gemmill, M.,

2004. The economic impact of pharmaceutical parallel

trade in European Union member states: a stakeholder

analysis. London: LSE Health and Social Care Special

Research Paper.

Liu, X., Pazgal, A., 2020. The impact of gray markets on

product quality and profitability. Customer Needs and

Solutions 7(3), 62-73.

Rong, L., Xu, M., 2020. Research on price competition of

transnational supply chain considering parallel import.

Business Research (4), 68-77.

Shang, C., Guan, Z., Mi, L., 2020. Analysis of government

subsidy strategy for green supply chain considering

dual consumption preferences. Systems Engineering

38(5), 93-102.

Su, H., Li, K., Huang, W., 2017. Choice of retailing

channels based on parallel imports. Journal of

Game Analysis of Manufacturers and Gray Market Speculators Under Different Government Policies

51

Northeastern University (Natural Science) 38(9),

1363-1368.

Su, X., Mukhopadhyay, S. K., 2012. Controlling power

retailer's gray activities through contract design.

Production and Operations Management 21(1),

145-160.

Wang, G. W., 2014. A study of stakeholders of gray

market (Master's thesis, Guangdong Academy of

Social Sciences).

Wu, H., 2017. Research on manufacturer’s price and

service strategy under gray market. Mathematics in

Practice and Theory 47(16), 10-19.

Xia, X. Q., Zhu, Q. H., Wang, H. J., 2017. Game model

for end-of-life vehicles between formal recycling

channels and informal recycling channel based on

governmental different policies. Journal of Systems &

Management 26(3), 583-591.

Yeung, G., Mok, V., 2013. Manufacturing and distribution

strategies, distribution channels, and transaction costs:

the case of parallel imported automobiles. Managerial

and Decision Economics 34(1), 44-58.

PMBDA 2022 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

52